#20ninescene

Why the My Chemical Romance Reunion Matters

by Marianne Eloise

12 November 2019

"I saw it and I'm crying and eating olives while getting ready for school," read a text from my 13-year-old sister after I confirmed that My Chemical Romance were, against all odds, reforming. Bizarre breakfast choices aside, the most notable thing about this exchange is the cross-generational love of MCR, a band that broke up when my sister was six years old. The exact reasons for that 2013 split remain unclear, but it's been pinned to everything from the band not being "fun anymore" to the members' personal issues. In a tweet at the time, Way said that he felt as if he was "acting" onstage.

Not every band expands its fanbase post-break up, but MCR have always been different. The mass hysteria that followed news of their reunion isn't just about nostalgia, and it's unlikely that their upcoming shows will be packed solely with people in their 30s reliving their emo youth. Fans from all eras are excited, mainly because MCR give us a lot more than just music: they make us feel seen and heard. It isn't easy being alive right now, but their songs about fear and trauma and survival provide comfort.

Of course, part of the reason fans are so excited is that we'd been uncertain this reunion would ever actually happen. In the years since the break up, emo and screamo has been pushed unexpectedly back into the mainstream, with MCR mysteriously absent. Bands like from First to Last, Funeral For a Friend and Motion City Soundtrack have reformed, if only for a few shows. New artists like Lil Peep and Lil Uzi Vert have worn their emo influences on their sleeve. When the emo revival hit around 2016, fans hoped MCR might return and claim their territory, but the band rebuffed the rumors. A decision to stay away would have made sense; frontman Gerard Way's solo album Hesitant Alien and comic book series The Umbrella Academy have been successful in their own right. Guitarist Frank Iero also has a solo punk project. With the intervening years seeing Way and Iero battling their own issues and Iero surviving a traumatic tour bus crash, it would be perfectly understandable if they wanted to move on. Selfishly, we didn't want to let them.

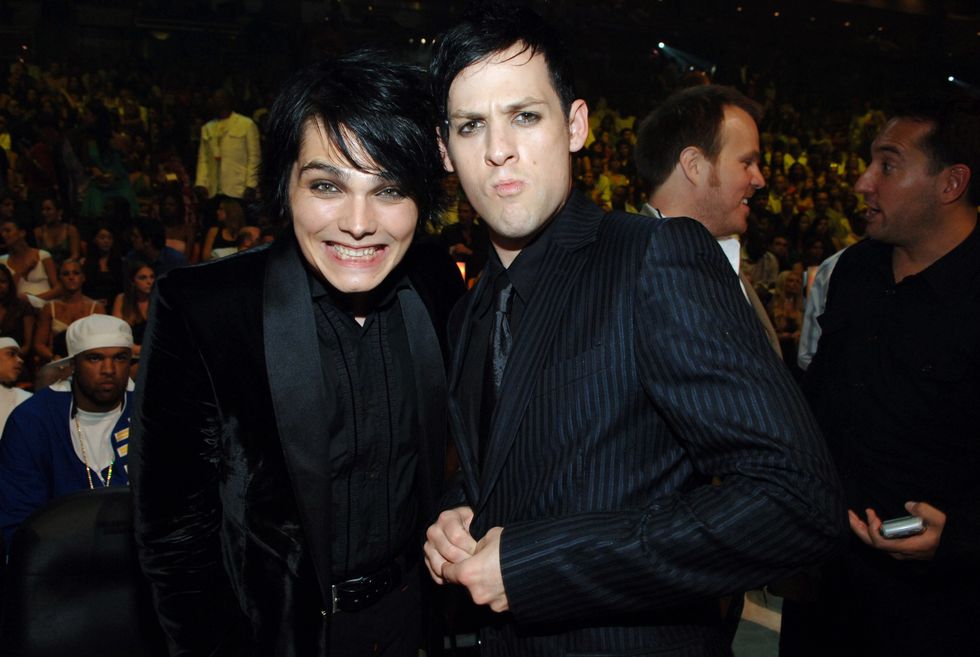

My introduction to MCR, like many people's, was "I'm Not Okay", the lead single from 2004's Three Cheers For Sweet Revenge. Already battling internally with my mental health and externally with my family and ever-cruel school bullies, I felt instantly understood. I enjoyed the sound, sure, but above all it was hearing someone yell "I'm not o-fucking-kay" in a way that felt real that touched me. Watching the music video and seeing Way and Iero storm through a school in uniform and make-up well into their 20s was weirdly life-affirming, for me and many others. The album was era-defining: addictive, blood-stained, murderous energy that felt brand new. MCR's melodramatic lyrics, over-the-top stage presence and visceral candour were like nothing I had ever heard or seen. I would listen to Way screaming about pills and poison and heartbreak on loop, despite having no real cause to identify with it.

Simply put, MCR's music was and is a lifeline for teenagers and adults struggling with their mental health. The band have always been open about what inspires and traumatises them, like depression, addiction, and crucially, 9/11. That openness has engendered a possibly false intimacy with their fans; they were never just in it for the merch or the music, but for the therapeutic quality of listening to a man who promised to be a savior of "the broken, beaten and the damned." Fans often claim that MCR "saved their life," and one Tumblr page gathers stories from people thanking MCR for the fact that they didn't take their own lives. It might seem dramatic, but for many teens, the message that they were not alone was crucial to survival.

The band's message has only gained more resonance over time. When I was a teenager ten years ago, nobody was talking about mental health in medical terms. I didn't have the language for what I was dealing with, but through artists like MCR, I started to realize that other people were struggling with self harm, addiction, or depression. Speaking on forums with other teenagers, I found a community of people who were honest. Perhaps this is why MCR appeals to teenagers now: Gen Z has expanded the rudimentary mental health conversations that we were having online in the 2000s into tangible advocacy and changes.

The members of MCR understandably found their accidental mental health advocacy a burden at times. Speaking to Spin in 2007 about the common claim by fans that MCR "saved their life,'' Way said: "Sometimes, honestly, I feel like we're moderating a support group. We tap into dark stuff from the high school years, and it's our responsibility to bring kids to a positive, nonviolent solution." His brother Mikey added that "the fans look out for each other" too. Of course, that responsibility took its toll on people already struggling within themselves. MCR's attachment to emo and their candor about mental health at one point led tabloids to blame them for the tragic suicide of a teenager. The vast majority of young fans had the opposite experience: they felt supported through the worst time of their lives.

Amy A, aged 29, tells me that at school, she loved alternative music, but didn't have a lot of friends to share it with. After Three Cheers came out, she was no longer the odd one out, "one day a group of girls came over and said, 'you like My Chem, come sit with us'" Amy tells me. "They mean so much to me as they were the first band that I and millions of others connected with. It opened up this whole other world where it was cool to be a loser, and with them returning, it's overwhelming to see the demand is just as great," she adds, and it seems that for many, being a fan meant no longer being alone.

Related | Does 3OH!3 Regret 'Don't Trust Me'?

Amy F, aged 26, agrees. After "graduating" from pop punk like Blink 182, Amy discovered MCR online. "Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge became an escape, and allowed little emo me to have a private community and an outlet for feelings that I didn't understand." She adds that when she got Myspace, she also gained "an entire community of people who were solely focused on this music too." She says that the comeback is further affirmation that MCR have had a profound impact on those who needed them.

Laura, aged 28, had almost the opposite experience. She fondly remembers the first time she heard MCR, and how at once transformative and alienating that was. "Emo was quite possibly the least cool aesthetic or music taste you could have, and aligning yourself with that genre essentially eliminated any chance of popularity among peers," she explains. Still, her devotion never wavered, and MCR's albums have served as a soundtrack to the past fifteen years of her life. "This comeback tour feels at most, like the start of a new era, and at the very least, an opportunity to say goodbye," she says.

We don't yet know whether MCR will release new music, but it's fun to guess what that might sound like. They've always been idiosyncratic, even within their own genre — many people joke that MCR, Panic! At the Disco and Fall Out Boy make up the "holy trinity" of emo, but the three bear little resemblance sonically and have all denounced the term. MCR took more influence from artists like Queen, Siouxsie and the Banshees and David Bowie than their peers; they made music that was less about crying alone in your bedroom, more about dramatically screaming your lungs out in a dirty basement somewhere.

They also had a campish, theatrical focus on storytelling. MCR started playing around with mythology as early as their debut I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, a concept album about two people who go on a rampage and get gunned down. Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge had a storyline of its own, too, centring on a man who finds himself in purgatory and is resurrected to commit a load of murders. They perfected the concept album with The Black Parade, a rock opera about an unnamed person dying of cancer and his experiences in the afterlife. While Black Parade was mostly well-reviewed, one bitter critic did say that the band had "ideas above their station." Still, MCR had the last laugh: Welcome to the Black Parade is now regarded as the Bohemian Rhapsody of emo.

Related | What Does Pop-Punk at 40 Look Like?

MCR always believed that they would be short lived, that they would only be around as long as they were needed. Perhaps what they underestimated is the long arm of adolescent angst. Emo is very different in 2019 – new artists are infused with elements of pop and rap, while older ones, like Fall Out Boy, have leaned wholly into mainstream pop rock. If MCR do make new music, it's likely they'll put their entire selves into making it as over-the-top as possible, befitting of our current hysterical times. If they don't, their impact is already assured. MCR created a world where emo is recognized, legitimate, and a part of the canon in a way it has never been before. Welcome back to the Black Parade.

Photos via Getty