#20ninescene

'To Write Love On Her Arms' Helped Keep Emo Kids Alive: Its Founder on What's Changed

13 September 2019

Twenty nineteen feels like a pretty awful time to be a live, particularly on the internet. One of the possibly unimpeachable improvements that's occurred online since 2006 however, is the revolutionized conversation around mental illness.

Talking with Jamie Tworkowski, the man who founded the viral Myspace phenomenon turned mental health advocacy organization To Write Love On Her Arms (TWLOHA) brings me back to a godawful time online when it was common to suggest that people who talked about self-harm or depression only did so because they "wanted attention." In the '00s, the conversation was largely limited to this kind of cruelty among teenagers. The hysteria of adults, who shamed kids in their own way by proposing overnight fixes and stigmatizing their refuges (music, online communities), didn't help either.

Related | Does 3OH!3 Regret 'Don't Trust Me'?

Romanticizing sadness and mental illness was, of course, a slippery slope in emo and scene corners of Myspace and Tumblr. But back before queer-theory-literate 6th-graders were using the word "trauma" on Instagram, TWLOHA was a force on the internet connecting the dots between expressing pain and trying to heal from it.

TWLOHA was born in 2006 when Tworkowski, then a 26-year-old Florida sales rep for the surf brand Hurley, made a Myspace page for a story he wrote about his friend named Renee, who was battling depression and addiction. The story went viral, probably, because it opened up a brand new world for teenagers, where the intensity of their pain was acknowledged, alongside an unpatronizing plot-line about hope. The story, along with the profile, logo, T-shirts and rubber wristbands, Tworkowski sold to raise money for Renee's treatment, quickly became inescapable online.

A year later, Tworkowski integrated TWLOHA into 501(c)(3). A few years after that, it was common for popular Myspace bands like Switchfoot, Evanescence, Underoath, Bayside — and later more mainstream acts like Paramore, 5 Seconds of Summer, Panic at the Disco, Boys Like Girls and OneRepublic — to add TWLOHA's page to their illustrious Top Eights and rep merch at shows. This time each year during National Suicide Prevention Week (NSPW), high schoolers' feeds were flooded with long personal posts and photos of wrists and forearms Sharpied with "love."

The group spent a decade traveling with Warped Tour. It's a contradiction that teases out the importance of TWLOHA: an organization that promotes sobriety and hope, partnering with a festival known for debaucherous partying, where teens came to listen to music that reveled in angst and sadness.

As we're beginning to understand in hindsight, some of the pop-punk and emo bands that played Warped Tour provided a rare outlet in American pop culture at the time, where honesty about pain and insecurity was encouraged. However, it was often unclear what came after the catharsis of the song, or the show. TWLOHA was an educator and a caretaker in that scene, providing the next step in a scene where it was casual for artists to sing openly about wanting to die and hating themselves. As Tworkowski puts it, TWLOHA was there to insist that "people deserve more than music" — that they deserved the honesty they sought online and at concerts, in their real lives and relationships, all the time.

Related | What Does Pop-Punk at 40 Look Like?

TWLOHA may have been more visible in Myspace's heyday. But today, it operates as a hub of mental health resources with the largest reach it's ever had. Best known for their merch, they've occasionally has faced skepticism about their impact. However, proceeds go entirely to scholarships for treatment and the salaries of employees — who respond to messages and work with their senders to secure affordable counseling, speak at universities and festivals, and put on community events like their annual "Heavy and Light" concerts. In 12 years, TWLOHA has responded to over 200,000 messages, and put an impressive $2.4 million towards treatment scholarships. This week, for their annual NSPW campaign, TWLOHA launched a new project called You Make Today Better: a week-long, day-by-day action plan to help people check in on themselves and others.

During NSPW, PAPER sat down with Tworkowski to hear about Myspace culture, the relationship between music and mental health, and what has and hasn't changed since he started TWLOHA.

How would you describe the culture of MySpace and the internet when TWLOHA started out?

2006 was really the moment when MySpace became mainstream, just a part of everyday life. I was 26, and I remember my friends signing up and talking about it. I dread the day when people don't know what I'm talking about when I say "MySpace." I had made a MySpace page for the story, and people began to respond. I wasn't an expert but when I signed up, I had a sense that it was moving quickly. What we were doing was different, because it wasn't an individual profile. Instead of an individual photo, it was (what would become) our logo. We were one of, if not the first, charity to do that. We became a charity but it was a grassroots, social movement to start. Obviously, there was also a big connection to music and that Warped Tour culture, which was pretty much synonymous with MySpace. Some of the first bands to support us existed in that space. It was kind of a perfect storm of all these elements coming together that allowed the story to gain an audience.

What was the conversation around mental health in 2006? Was there one?

There was a lot of ignorance and ugliness and bad ideas back then. People thought, "Oh these are issues that affect young people" or depression is "something that affects teenage girls who listen to this kind of music." There were a lot of stereotypes of the Warped Tour and alternative music scene, within MySpace. Things feel healthier today. Certainly bullying, ignorance and ugliness have been around since long before MySpace and they still exist today. But people are more aware, and you see it in so many different circles, whether it's pop culture, music, sports, Hollywood, just in all walks of life people are talking about mental health, talking about suicide, talking about addiction.What was the tone around "emo" at the time?

Emo was such a buzzword at the time. There were people who said, "oh this, you know, self injury or depression" that's just this emo thing, a trend almost. It's always been important to kind of push back on that, and say "no this stuff affects people all over the world, of all ages, no matter what music you listen to, no matter how you wear your hair, or what clothes you wear, like this is part of being human." Or like "they want attention." The flip side is that the word "emo" is short for "emotional." I think it's Adam Duritz from Counting Crows who had this quote, years ago, where he said like "Well isn't that the point of music? Like of course it's emotional." Like the whole thing is so like... [Laughs]... of course it's supposed to move you, why do any of us listen to music?How did TWLOHA go from being an online campaign, to an organization on the ground?

We still use the same tools. There's no shame in using social media. We use social media to bring hope and encouragement and information to people. T-shirts raise money to allow us to do what we do. I actually love the fact that a lot of the same elements that we started with still exist, you know? There's no part of us that thinks "Oh social media or T-shirts are shallow or silly." We still love merch, we still use merch. A tweet at 2 in the morning can matter. We consistently use social media to try to bring hope to people who are struggling. That will always be part of what we do. Now there's just more people on our team, more programs and more ways for people to get involved.

Hayley Williams from Paramore (Photo courtesy of Jessica Bennett)

Tell me more about TWLOHA and the music world it was connected to.

Music has always shared a lot with the mental health conversation, because music is about being honest. Music tells us that we're allowed to feel things deeply, that we're allowed to ask questions. We go to concerts and sing about things we couldn't say to a friend over coffee. So we love music as like a starting point, in terms of, "hey what if the things you love about music, what if you deserve to have that beyond music as well? What would it look like to be that honest in your relationships, or to express these questions in a counseling environment?" We have so much respect and admiration for our friends who make music because we think it's so powerful, and there's a lot of synergy there.Yeah, those pop-punk and emo bands weren't taken very seriously, but they were talking about serious stuff. I guess the best example being "Adam's Song" by Blink 182.

Yeah! The very first two bands to support us were Switchfoot and Anberlin. Switchfoot always existed in a unique space, not so much in the Warped Tour world. There, we met folks like the Underoath guys, Bayside, The Rocket Summer. As Paramore was coming up, Hayley was very supportive. Then over time Amy from Evanescence and Dustin from Thrice have also become good friends. We've gotten to know a bunch of really gifted spoken word poets as well, and folks beyond music, whether it's athletes or actors.

In that era of MySpace and Tumblr, it felt like there was sometimes a romanticization of mental illness or suicide or self-harm. And stuff like TWLOHA was kind of the missing link. You guys brought really crucial education and resources into a space where ignorance was really dangerous,.

I would agree with that. A lot of the bands I mentioned, I'd like to think are known for being hopeful. Not just songs that express "this is how sad I am" or "this is how life is." I mean, those bands did give people permission to just express "this is how sad I am, this is how much it hurts." We want to invite people to be honest about that, but not just stop there. We want to invite people to get better and to get help. We want to convince people that they deserve more than music. To tell them that it's not enough to cry and sing loudly along to your favorite band. We wanted to tell people if you're really struggling, you deserve to be that honest all the time, with friends, with family members, you deserve whatever help you need, for however long it takes. That the way you feel today, you may not feel tomorrow, so please stay alive to get better. We love the idea of music as a starting point again to begin the conversation.

Right, and then you need a certain infrastructure to take the next step beyond expressing yourself.

We think about the idea that music moves us. That idea of movement, it's like, "okay moves us from where to where?" We want to move people from isolation, to honesty, community and support. We want to move people from hopelessness to hope. I love the idea that music can be part of that process, but the thing we really dream about is someone sitting across from a counselor or stepping into treatment or texting crisis text line, taking real steps in the direction of whatever help they need.

TWLOHA at Warped Tour (Photo courtesy of Big Picture Media)

To Write Love On Her Arms went into physical spaces and actually travel around with Warped Tour. What was that like?

I think we did 10 summers, the last 10 summers, every single date. We would rent bunks on a band's bus. Typically two people would be out for the whole tour all summer. They'd be responsible for the whole operation, in terms of setting up the tent and talking to people, having conversations throughout the day, selling T-shirts. Then we'd also have volunteers, former interns or people that we got to know who would come back each year. That was a big part of our history and our story, as far as people finding out about the organization.

Out at those shows, were you guys just raising awareness, or offering counseling on the spot, or just being a resource in general?

It was a whole mix. Some people would want to come up and share their story, their experience with these issues. For someone else, they're just asking, you know literally "what is this?" "what's To Write Love On Her Arms?" Sometimes it was "do you have that shirt in medium?" and and other times it was "I'm really struggling today, what do I do?" Then there was also a sort of this summer camp vibe where, you know, it's almost this traveling circus that our team becomes a part of, with all the bands, the crew, the production. So all of these people who are living life together out on the road for a couple months each summer.

Sounds like a lot of fun. One of my colleagues just did an interview with the Millionaires about their time on Warped Tour, they had crazy stories.

Yeah, obviously for us it wasn't totally a party, since we were there representing sobriety. But I think our team had a lot of fun and built great relationships. The irony is not lost on us, in terms the fact that Warped Tour is not exactly synonymous with being hopeful or positive. There's even irony to the fact that, one week our shirt was the best-selling shirt on Hot Topic, which is certainly not synonymous with hope. Ultimately what we want is for people to encounter hope. We come back to the idea of wanting, to move people out of their pain, out of their struggle, their break-up, grief, parent's divorce, whatever it was.

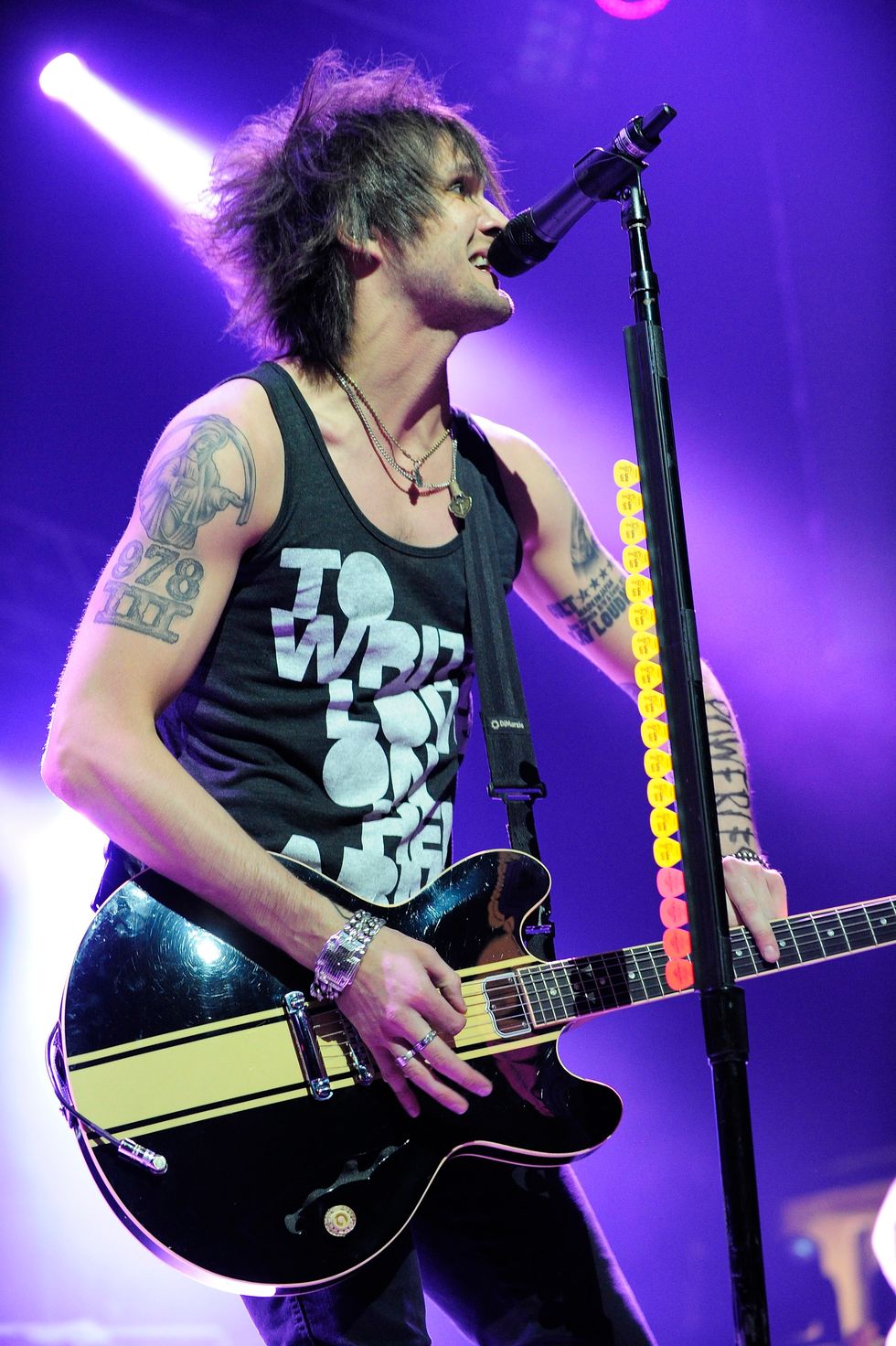

Martin Johnson from Boys Like Girls (Photo via Getty)

Right, and there was such a need in that community.

Yeah! I think some sides of that community would surprise people. Like, on Warped Tour, there were 12 step meetings that took place everyday. It's like the internet or anything else. There's lots of corners of it. Some people wanted it to be wild, it was wild. But for other people, there were specifically there pursuing sobriety and community.

You've watched from the front lines how drastically awareness and information around mental health has increased over the last 10-15 years. What has watching that change been like?

It's a mix. You smile and feel good about the progress. Just today — I'm a basketball fan — and I just saw a headline that said every NBA team is required to have a licensed mental health counselor on retainer for next season. There are all these wins, there is progress. But we're constantly reminded of both ends of the spectrum. We still hear from families who've lost a loved one to suicide, or to an overdose. And then I meet people who say "I'm still alive because of your organization" and have our logo tattooed on their shoulder. Both extremes remind you what's at stake. The person who says "I'm alive, I'm sober, I'm getting help," obviously that's so encouraging. That motivates us to continue doing this work. There are always new ways to understand it. I think a lot about the intersections between mental health and gun violence, between mental health and immigration. You know, 22,000 Americans die by suicide with a gun every year. All of a sudden it's like "okay well if we're talking about suicide prevention, we also need to talk about gun violence and access to guns." That's been some of the evolution or the progress as well.

Initially, there was some confusion about whether or not TWLOHA had Christian ties. Could you talk through that?

Sure. We're not a Christian organization. It's not a requirement to work here, it's not a part of our work. In the original story, some of what might call "Christian language" shows up. But that wasn't a business plan, or a mission statement. It was just me writing a story, and the language reflected my life at the time. I'm so thankful that over the years we've been able to serve different people who believe all different things. However, we are inviting people to ask big questions — things that come up when you're thinking about depression and suicide, like, "is like worth living?" "am I lovable?" "can I start over?" "can I get sober?" We don't feel any pressure to be a one-stop-shop that answers all those questions, for all people. We're not trying to get you to end up in a church. I'm 39-years-old. My faith continues to evolve as I wrestle with the world. I want to invite other people to have that process as well.

Lead Photo via Getty