The 2010's were mostly cursed: a glorious, yet infuriatingly chaotic decade during which shifting politics, technology and social media played a lasting role in how we consume and react to the world around us. Trends in music, which swung wildly from the Svedka-bottle throb of EDM to trap-inflected everything (and many fusions of both), were equally as disorienting. While it remains to be seen how history books will define the '10s, musicians made album-length statements that valiantly rose to meet the challenge of doing so.

Related | PAPER's Top 10 Songs of the '10s

Azealia Banks pushed rap to more artistic, provocative heights, while famously pissing everyone off. Fairweather reality stars made unapologetically shallow pop with enduring cult appeal. White people finally found out that Beyoncé is Black, and she doubled down. After a decade of frenzied output, Rihanna learned not to give a fuck and made her best work yet. Lana Del Rey spelled out accurate visions of doom and hope, while ANOHNI warned the world of its inevitable day of reckoning.

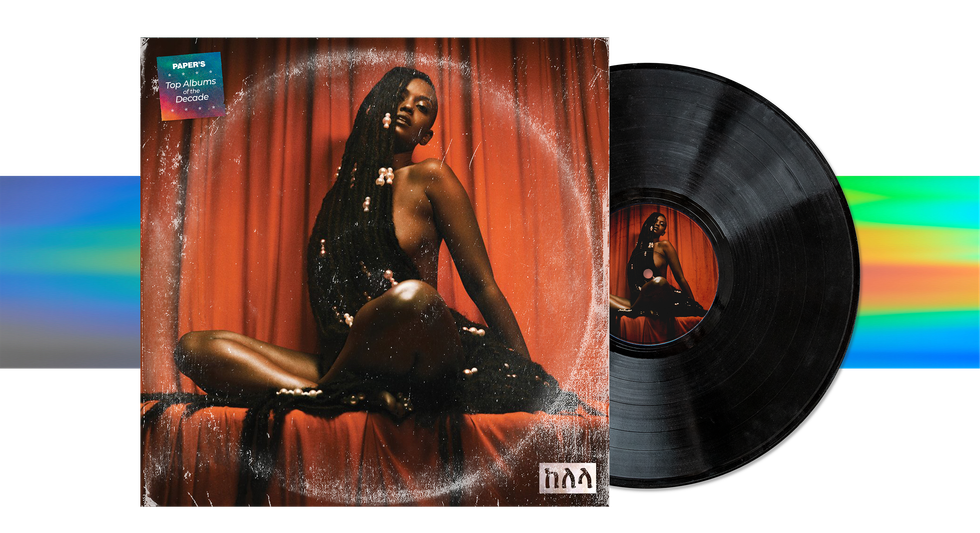

On R&B futurist Kelela's 2017 album Take Me Apart, she lets her emotions take up space. As a result, Kelela produced a project that's gloriously tumultuous and seductively complex, assisted by heavyweights like Arca and Jam City.

Sometimes the space surrounding Kelela's observations takes the form of extraterrestrial silence, as heard on "Jupiter." Other times, the space is inhabited by warring breakbeats, like in "Onanon," where Kelela dances an endless tango with a lover: "We're not in a race/ You're running away/ We're spinning around." Elsewhere on the record, Kelela is nostalgic, channeling genre forebears like Janet Jackson and SWV on "Waitin'," where she runs into an ex and lust instantly rushes back. "Saw you there and it fucked me up/ Now we're back to where we started from," she sighs.

It remains to be seen exactly how Take Me Apart will influence future genre-blurring R&B stars, but we can already hear similarly versatile stylings in music by singers like Ella Mai and Normani, who are dabbling in the sci-fi sounds that Kelela helped popularize this decade. But she must already understand this album's impact, given how last year, she produced an imaginative, remixed version with DJ Asmara and a legion of other queer, POC collaborators ranging from Serpentwithfeet and Joey LaBeija to Ms. Boogie and CupcakKe.

"I wanted to create an institution so the next time I do a record, it's just known that this spirit of inclusive collaboration is a part of my identity as an artist, and that we reach people who don't have access to that, who may not have been immersed in that world, and we keep them there," Kelela told PAPER in 2018. In doing so, Take Me Apart quietly embodies the R&B renaissance that captivated the '10s while uplifting an unsung class of innovators behind it. — Michael Love Michael

Breathy, sensual, enigmatic and a little bit alien, FKA twigs stands in a class of her own. With an all-encompassing vision of the world she wants her music to inhabit, FKA twigs' highly anticipated 2014 debut, LP1, introduced us to her unique blend of R&B vocals and experimental electronic beats. We've been entranced ever since.

Opening the album with the mantra "I love another and thus I hate myself," twigs takes us on a journey through the many ways in which love warps our sense of self. Swinging from seething jealousy on "Video Girl" to luxuriating in hopeless infatuation on "Hours," twigs all but obliterates herself for her lovers in a tragically beautiful way. A dancer by trade, there is a visceral quality to twigs' music; the stuttering drums of "Pendulum" rocking back and forth like a creaky ghost ship still rattle my vertebrae to this day.

Working with producers like Arca, Clams Casino, Sampha, and Dev Hynes, LP1 felt like it was beamed back from the future — simultaneously of the moment and so far ahead of its time. — Matt Moen

No one can get in your head like Lorde. Why? No one else can pull off her cocktail of self-awareness and romanticism. The 23-year-old New Zealander makes pop music that's deeply introspective, while also capturing visceral pleasure and pain. She offers complex feelings, delivering cheeky commentary on her own emotions in real time, but never gets bogged in explanation. That's why a signature Lorde lyric can be a perfectly-crafted turn of phrase, ("I care for myself the way I used to care about you") or a perfectly simple one ("Hand under your t-shirt/ Know I think you're awesome, right?"). Both lines kick you in the chest.

Melodrama testifies to the most written-about topic in music: a break-up. Lorde doesn't try to resist archetype. Instead, as the title promises, she brings clichés (the falling-in-love, the escapist night out, the rose-colored flashback) alive with vivid urgency. The secret is how she collapses the romantic timeline. We know from the first song that Lorde will wind up dancing alone. But there's no real beginning or end on Melodrama, no happy or sad songs. Lots of musicians are skilled at bottling feelings just so and Lorde is as good as anyone. But the magic of Melodrama is how the full, messy arch of the story — the crush, the good days, the rupture, the fall-out, the relapse and the rebirth — feels present on each song.

The good-times songs are full of poison. The self-destructive party songs reach out for stability. The most devastating songs are also the cracks where the light floods in. On "Sober," when Lorde and her lover were still "King and queen of the weekend," mounting affection is characterized with a warning: "Acting like I don't see/ Every ribbon you used to tie yourself to me." "Writer in the Dark," an anthem of manic obsession ("I love you till you call the cops on me") ends with Lorde comforted by stable routine ("I ride the subway/ read the signs"). Lorde wonders if she and her lifestyle are simply too messy for love on "Liability," which transforms into a talisman of self-possession. The way Lorde tangles her story, while keeping you on the edge of a knife, is in perfect harmony with Jack Antonoff's epic, dissident production, which screws up all the math of pop melody. The result is as varied and confounding, as pleasurable and painful as heartache itself. — Jael Goldfine

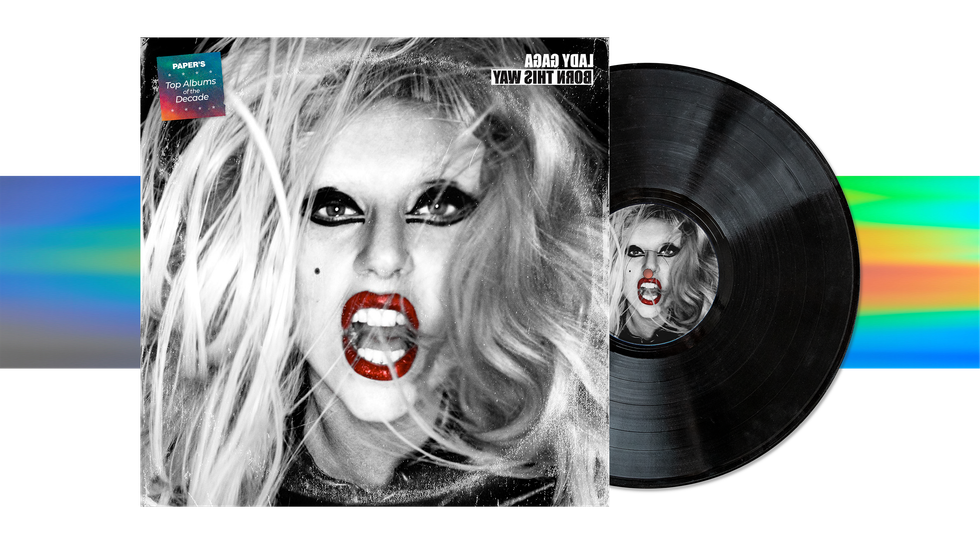

Born This Way is bigger than Lady Gaga. Its first single and title track became a mission statement for the pop icon's entire career, normalizing the LGBTQ experience on a world stage and, most importantly, putting the word "transgender" on Top 40 radio.

This celebration introduced her 2011 epic, which packed together themes of youth, rebellion and freedom inside production that bridged the distant gap between Bruce Springsteen Americana and seedy Berlin electronic. With allusions to Christianity throughout and cover art suggesting Gaga was the vehicle for a new generation, Born This Way was decidedly ambitious — and entirely singular.

This era delivered some of Gaga's best-known anthems to date, from her pre-Joanne country bop "Yoü and I" to the massive '80s crescendo of "The Edge of Glory." But it's Born This Way's deep cuts where Gaga unleashed her strangest, most intricately coiled concepts. "Heavy Metal Lover" and "Government Hooker," two standouts, saw shiny metallic synths and grinding, machine-like bass get layered beneath twisted lyrics only Gaga could conceive: "I want your whiskey mouth all over my blonde south," she demands on one. "I'm gonna drink my tears tonight," she confesses on the other.

Then there's a hair metal-broadway baby hybrid ("Hair"), an ominous guitar-led hook-up song with church bells ("Electric Chapel"), a ferocious dance cut where Gaga purposefully butchers the German language on beat ("Scheibe"), and an eerie, melodic pop-opera with cultish chants and Gaga's piercing shrill ("Bloody Mary").

While music trends are typically ripped from the biggest stars and repeated ad nauseam, nothing has come close to sounding like Born This Way since its release nearly 10 years ago. And that's because nobody could possibly replicate the oddities that boil inside Gaga's brain, especially from a time when she was consistently unleashing some of the most provocative visuals, songs and ideas into mainstream pop culture. — Justin Moran

On Rihanna's superior cover of Tame Impala's "New Person, Same Old Mistakes," she drops the first half of the song's title and the "d" in "old" to embark on a wildest astral trip of her life, thick Caribbean accent piercing through the fog. "Feel like a brand new person," she sings.

With 2016's ANTI, the Barbados superstar not only broke new artistic ground for herself, following a relentlessly consistent output of trendy dance-pop smashes, but she created the album superstars like her make when there's nothing to lose. She's certainly earned it, spending the first half of the decade churning out an album a year and promoting them on sold-out world tours before age 30.

Rihanna's now-permanent identity as an inimitable tastemaker emerges on ANTI's eclectic tracks. "Desperado" casts the wistful lone ranger in full, high-fashion yeehaw getup — clomping industrial beats and all — well before its ubiquitous pop culture resurgence this year. On "Higher," she's whiskey-drenched and literally hollering 3 AM booty calls when the liquor gets her feeling pretty. And on "Consideration," she makes it clear she's doing things her way from now on, while nabbing an early collaboration with SZA, who would have an explosive breakout the following year. Rihanna's impact. — Michael Love Michael

Heidi Montag capped off a 2000s trend of tabloid celebrities releasing music, and ushered in a 2010s phenomenon of reality stars becoming serious, multi-faceted entrepreneurs. She was ostracized for today's new normal of "famous for being famous" influencers whose careers thrive on seeking validation and altering their appearances. And her first and only full-length album, Superficial, was released in the fire of all this public scrutiny, making it both a commercial failure and a now cult favorite.

With a $2 million investment from Montag herself, Superficial was manufactured by some of the biggest producers and songwriters in pop music. She onboarded names like Cathy Dennis, who was behind Britney Spears' "Toxic" and The Runners, who'd go on to produce hits off Rihanna's Loud. She spent "entire nights and days in the studio," and sometimes cried from exhaustion. "I can't even count how many hours — literally blood, sweat and tears," Montag told PAPER in 2018.

Though Superficial sold just over 1,000 units in its first week of release, The Hills alum's hard work made for a blueprint of all the materialistic, trash-pop that musicians like Slayyyter and Kim Petras create today. Its title track is a swirling synthesized ode to paparazzi flashes and luxury sports cars: "They just mad cause I'm sexy, famous and I'm rich," she accuses, her robotic vocals drenched in autotune.

Other highlights like "Turn Ya Head" and "Look How I'm Doin" are platinum blonde, bandage dress, bottle service club bangers, while "One More Drink" and "I'll Do It" deliver sexed up, irresistibly cheap bops. — Justin Moran

Standing alone at the end of the decade as her first and only studio album, Broke With Expensive Taste is the delicate masterpiece of NYC native and musical firebrand, Azealia Banks.

When EDM pushed the charts to a saturation point in the mid-2010s, Banks delivered a blow that promised to only be the beginning of her reign — when in retrospect, BWET's critical success was the beginning of the end. Banks' legacy may not be what places the bass-blasting 2014 record on a trophy shelf next to a roster of music's greats, sure, but "212" alone will.

Put it next to the UK garage-influenced "Desperado," the enduringly destructive "Yung Rapunxel" and "Heavy Metal and Reflective," and you've got enough to credit Banks with one of the most compelling discographies of the 21st century. — Brendan Wetmore

ANOHNI's HOPELESSNESS was a wake-up call, imploring us to examine our complacency in a social system built on patriarchal violence and bleeding the planet dry. On the album, ANOHNI leans into an indignant fatalism in an effort to expose the apocalyptic harm that comes from our inaction, from wishing a drone strike would "explode [her] crystal guts" to wanting to see "dogs crying out for water" and "fish go belly-up in the sea" on "4 Degrees."

Working with producers Hudson Mohawke and Oneohtrix Point Never, ANOHNI uses electronic dance music to amplify her emotional appeal, whether it be through the beating of war drums ("Crisis" and "Marrow") or intricate synth melodies ("Obama" and "Violent Men"). On the album's title track ANOHNI wonders, "How did I become a virus?" and places the blame squarely upon herself. "I've been taking more than I deserve/ Leaving nothing in reserve." She confronts the difficult truth that we have let our greed go unchecked and now must face the consequences. Almost four years later, HOPELESSNESS begs the question: has anything changed? — Matt Moen

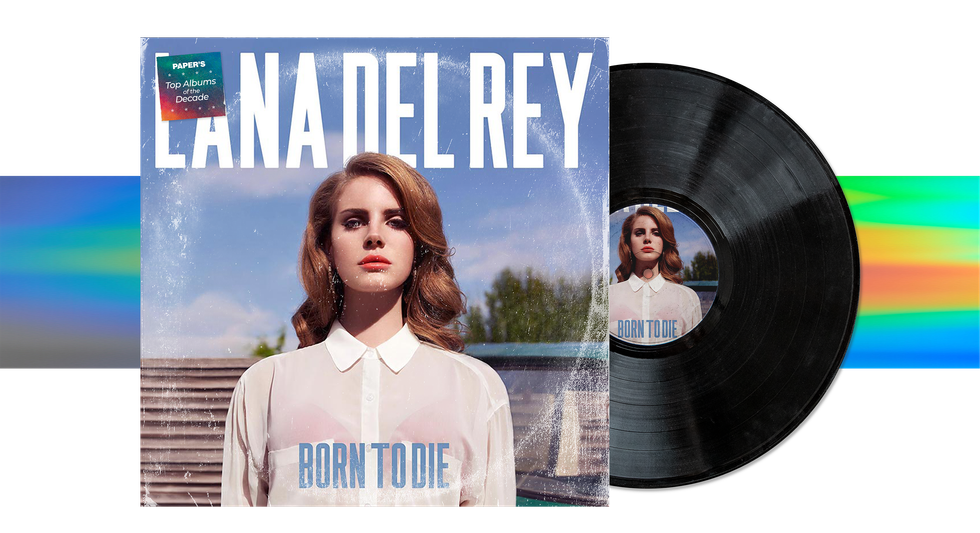

With her debut album, Born to Die, Lana Del Rey became the first artist of the '10s to find substance in melancholy. Setting off a domino effect of experimentation with sadness as an instrument, Born to Die exists in the pop canon as a deeply unsettling hit record that was never meant to be. In theory, Lana's smoky touchstones, from the inaugural ("Video Games") to the universal ("Summertime Sadness"), should have never taken off.

In 2012, generally depressive tracks didn't fit in the post-apocalypse scare landscape of celebratory dance songs on the radio. Somewhere, somehow, Born to Die grew its niche audience; first, in queer sub-communities on Tumblr, and then on a viral scale, thanks in part to Lana's retro aesthetic and fascination with controversial lyrics and themes ("Lolita"). — Brendan Wetmore

For what felt like years, Lemonade was all we talked about. The seismic surprise drop that commanded the internet for a week, cementing Beyoncé as our most powerful culture-maker. The album's recoup of Black American history, which employed artifacts from Yoruba deities to Yeehaw to interrogate the intergenerational impact of slavery on Black families. The post-genre sound (also a history of Black America) which spans the continuum of pop, R&B, rock, country and hip-hop, including collaborators like James Black and Jack White, and samples ranging from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs to Father John Misty to Led Zeppelin. The Grammy loss to Adele.

The album unleashed a matrix of contradictory conversations about the author herself. Beyoncé as champion of vulnerability ("I'm not too perfect/ To ever feel this worthless"). Beyoncé as perfectionist auteur, art-directing herself crying. Beyoncé as Black revolutionary, performing at the Super Bowl in front of a sisterhood of Black Panthers. Beyoncé as Black capitalist ("Always stay gracious/ The best revenge is your paper").

Within a year, college courses dedicated to using Lemonade to study race, gender and feminism were open for enrollment. As many Lemonade essays ended: "You know you're that bitch when you 'cause all this conversation." Lemonade electrified the conversations we began the decade with. We'll be having the ones it started well into the '20s. — Jael Goldfine

As chosen by Justin Moran, Michael Love Michael, Jael Goldfine, Matt Moen and Brendan Wetmore