Don't Cry for Kesha

Story by Jael Goldfine / Photography by Oscar Ouk / Styling by Christopher HoranFeb 20, 2020

"I'm a nihilist, in that I think nothing matters," explains Kesha, gazing at a drowning mammoth. "Sometimes. Then I think what really matters is just being kind. I have an existential crisis about once a day, on the low end."

We are wandering the La Brea Tar Pits, a liquid graveyard of prehistoric Los Angeles preserved as a tourist attraction, discussing the 32-year-old pop star's new album High Road. Kesha's YouTube-worthy bird-of-paradise eye make up almost blends in to the surroundings, but her pinstriped button-down, white sweats with rainbow piping, and massive bedazzled Gucci sneakers add an anthropocene touch.

We had planned to meet at the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine, the glossy Palisades meditation center that Kesha visits "as often as she can." Spirituality is important to her: she's been "obsessed with religion" since receiving her first kiss at a Nashville megachurch and attending a Catholic high school where the cool kids loved Jesus and listened to Switchfoot. Homophobia and false piety eventually alienated Kesha from Christianity and she's since settled on a non-denominational cocktail of meditation, mindfulness, and astrology. She's a proud double Pisces, uses Pattern (not Co-Star), and says Ram Dass' Be Here Now changed her life.

But a glitch in her packed press schedule finds us instead by the more centrally located drowning mammoths, chatting about nihilism as the lagoon emits lackadaisical farts of methane. Kesha has adopted the term to describe her new devil-may-care attitude, captured by High Road's first two singles: "Raising Hell," a thumping Big Freedia feature, and "My Own Dance," a marvelously self-aware recoup of the public view of her journey from pop hellion to #MeToo heroine. I tend to think of nihilists as Bushwick bros who wrote in "Frank Zappa" in the 2016 election, so I'm having trouble squaring the term with the colorful, animated woman next to me. But I know the term is crucial to the new era of Kesha: this shaggy brunette, detailing her methods for staying centered, while shrugging off the meaning of life.

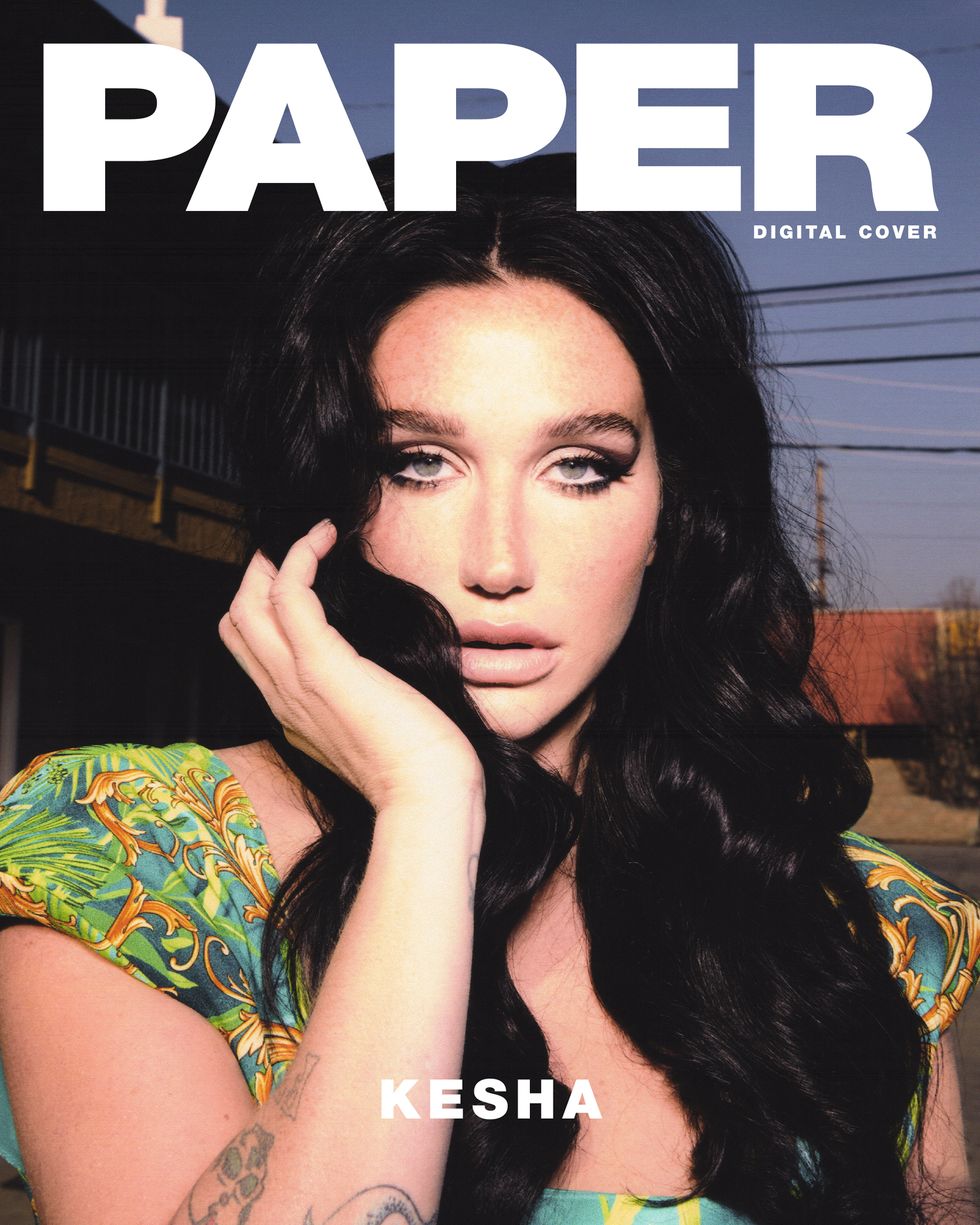

Dress: Versace, Necklace: Dalmata

In 2014, Kesha accused her former producer Dr. Luke of rape, emotional abuse and causing her to develop an eating disorder. In 2016, the New York State Supreme Court denied her request to break her contract with the producer and his label Kemosabe (an imprint of Sony), dismissing her case on the basis of jurisdiction and lack of evidence. She's since lost or dropped the rest of her claims. This February, Dr. Luke (aka Lukasz Gottwald), who denies all accusations, won several significant pre-trial arguments in the nearly $50 million defamation lawsuit he filed in 2014 against Kesha, who's also been ordered to pay $374,000 in interest on late royalty payments. (Christine Lepera, the producer's attorney said in a statement "Dr. Luke looks forward to the trial of his case where he will prove that Kesha's other false statements about him were equally false and defamatory.") Per her legal team, Kesha plans to appeal.

But in the faraway parallel universe of public opinion, Kesha unequivocally triumphed. Famous and powerful women rallied around her. Fans held #FreeKesha protests outside Sony's offices in Nashville and New York City. Most importantly, she embalmed her trauma into 2017's Rainbow, a No. 1 album that earned her critical praise and public approval like she never knew as the glitter-crusted party girl of "Tik Tok." As her story has become retroactively filtered through the explosion of #MeToo, she's been identified as one of its fuses.

But on paper, Kesha lost. And, after watching her career nearly end, she has committed herself to a kind of preservational single-mindedness. "I obviously care about what other people do, especially politically, because it's affecting the entire world. But for me? I just want to write music that makes people feel good. This record is me being like 'Fuck the world,'" she says, flashing me an ankle stick-and-poke of the phrase, punctuated by a tiny, doodled flower. "I'm going to be as happy as possible because I could get hit by a bus in ten minutes. So fuck the world — in the most beautiful way."

For Kesha, the prospect of never releasing music again — a future she prepared for after her legal loss and before she reached a compromise with Sony for releasing Rainbow — was a death sentence. "It sent me into a complete spiral," she says, gazing solemnly out at the mammoth scene. Kesha can't talk about her legal conflicts and hasn't said Dr. Luke's name in an interview for years. But she brings this period up when I ask how she got into meditation. "I needed a way to find peace with it, if I never did get to put out more music," she recalls. "I couldn't cope with it. [Making music] is all I've ever worked for. I've had one sole focus, one source of meaning in my entire life, and then... It was fucking terrifying."

What of the fact that her joyous, eccentric new album, just like her last, was released on Kemosabe — the label imprint that Dr. Luke founded? Although Sony cut ties with Dr. Luke in 2017 and he's no longer producing her albums, Kesha is still in the same six-album recording and publishing contract she signed with the producer at 18, meaning that High Road likely required his sign-off and will potentially benefit him financially. "I don't even think about that," she says.

If Rainbow was Kesha's ninth life, High Road is her tenth. She doesn't plan to spend her resurrection grieving. "Tonight is the best night of our lives" she promises on opener "Tonight." "We've got it all if we're alive... If we're still breathing, we're still breathing."

The words are slurred with a familiar tinny edge. A few notes later, and I'm 13 again, wearing an Aeropostale baby tee, fist-pumping in a middle school gymnasium. It's all back on High Road: the autotune, the half-rapping, the Radio Disney beats, the crass candor. Kesha is at the height of her "Tik Tok" powers on the album's set of deranged, contagious bangers, which neatly distill her version of nihilism. When the past is painful, the future precarious, and you ended up getting sued for trying to change the world, "Does it feel good?" becomes a prudent motto.

Dress: Versace, Necklace: Dalmata

"Look at the world we live in, what the fuck else are you gonna do?" Kesha laughs, examining a regal-looking vulture skeleton, when I ask if she parties much. "Everybody asks me about partying like I'm 4,000 years old and have died, or need a wheelchair. People are shocked that at the ripe, dear old age of 32, I still go out." Her best night in recent memory was a movie premiere where she hung out with kindred spirits Nicholas Cage ("we both just like weird, random shit") and Marilyn Manson.

Although High Road revives her '00s sound, it retains Rainbow's depth and tenderness. It's tangled with plotlines that have nothing to do with her record contract: a duet with her best friend and co-writer Wrabel, a song about growing up without a father, a fuck-you to a traiterous friend. One track ponders what life would be like with an old flame (she's been with boyfriend Brad Ashenfelter for six years). The album is a gloriously random indulgence of Kesha's every whim (see: "Potato Song (Cuz I Want To)"). Even when this doesn't pay off musically, it's delightful to hear Kesha doing whatever she likes, and see her plunge the expanse of her emotions, between the urge to get crunk and transcendent vulnerability.

"I feel like I'll be fully seen on this album," Kesha says, aglow. A few moments prior, two teen girls approached, so one could inform her that "Praying" "makes her heart hurt." Groaning humbly, Kesha requested a hug and offered a photo just as her team descended on the scene (lest other museumgoers get any ideas). Does she get tired of it? "Honestly? That's my favorite part. Like I told you, nothing fucking matters. But if me writing songs makes somebody else happy, than thank fuck. If I can spread just a tiny sliver of the good stuff, before I turn into manure, I think that's the goal."

Despite her adoring Animals (as her fans are known), Kesha never bothered trying to be likeable. She'd always felt like a misfit, going back to her Catholic school days, so she happily took up the role of delinquent in her class of 2010s pop stars, next to Taylor Swift's valedictorian and Gaga's art girl. She positioned herself as an antagonist and outcast, claiming the Twitter handle @keshasuxx "before anyone else could." (She changed it to @kesharose, around the time she started working on Rainbow).

Kesha also knows exactly what her music sounds like. "It just comes as second nature to me to write the cheesiest, stupidest, ten-year-old kind of pop. Just full sugar-pop," she says. But until now, it hadn't been clear if "Ke$ha," the sound and persona she crafted alongside Dr. Luke, was a costume she'd been forced to wear (she dropped the $ after going to rehab for an eating disorder in 2014). Kesha vigorously shakes her head at this narrative. "Ke$ha will always be a part of me," she says. "Those songs are my babies, too. It's just when I write songs, I usually write about fifty. Back then, I legally had no control over what was released. So the perspective of who I was was not complete. I wasn't being fully represented."

Post-Rainbow, too, she found herself the recipient of seemingly endless praise for an album that only reflected part of who she is. The same critics who'd misdiagnosed Kesha's reliance on autotune and singing about partying as crutches rather than deliberate statements, waxed poetic about her vocals and honesty. The same parents who'd had a moral panic about "Tik Tok," gave them the Rainbow vinyl for Christmas, tucked into a pussy hat.

"Yeah, that was confusing," Kesha concedes. "That it took people all over the world having to know private information, that was incredibly tragic and traumatic, to have kindness for me and be thoughtful about my music... I just wonder about the human condition of having to see someone torn apart before you want to be kind to them."

Reflecting on her first three albums, Kesha exclaims, "Oh my god, I took so much shit!" Eventually, she decided to run with it. "I was like, 'well, everyone thought I was fucking Satan, so I might as well just make a joke about that."

Dress and earrings: Alessandra Rich

By this point, we've settled on a bench by an animatronic saber-tooth tiger. When she sees it, Kesha excitedly pulls up her shirt and pulls down the waistband of her sweats to show me a large tattoo of a snarling blue tiger, inspired by a fantasy she had as a kid about having a pocket-size, winged tiger for a friend. It's extremely Kesha to have a bad bitch tattoo inspired by a dream that sounds like a Pixar movie.

Thus, High Road, on which Kesha demands full, contradictory humanity. "You're the party girl/ You're the tragedy/ But the funny thing's/ I'm fucking everything!" she screams on "My Own Dance."

At last, High Road resolves the dichotomy between Kesha and Ke$ha. Her unruly alter-ego actually appears on "Kinky" — a return to Kesha's ahead-of-her-times sex positivity. Back in 2010, before playfully objectifying men got you labeled an inspiring feminist, Kesha did so on songs like "Die Young" ("That magic in your pants is makin' me blush"). On High Road, she's graduated to espousing the value of consensual fetishplay, and honesty in open relationships.

Rooting herself in duality, Kesha now refuses to play favorites between the sides of herself, just because some play better with critics. "Making Rainbow was this intense, emotional breakdown of all the fuckery in my head of all the emotions and experiences I've had," she continues. "But on "Rainbow" [Rainbow's title track], I promised myself I would find a rainbow. I feel like High Road is me living in that rainbow that I promised myself."

There's a certain dissonance to hearing Kesha say she's "living in a rainbow," while paying out royalties to someone she says abused her, and facing the reality that Dr. Luke is at large in the music industry, working with young women like Kim Petras and Doja Cat. Despite the euphoric quality of High Road, and the way she talks about it, it's tempting to feel a twinge of sadness for Kesha and the terms of her current career.

But don't.

Three years after the rise and plateau of #MeToo, the disconnect between brave storytelling and justice is painfully clear. Kesha's not being naive by putting up the necessary blinders to train her gaze on the future — she's being shrewd. She's chosen life over martyrdom, her humanity over being a symbol. This tenacity doesn't call for mourning.

It's taken Kesha time to arrive here. For a while, she toyed with a legal career, and considered dedicating herself to contract law reform. In a 2016 Instagram post, in which she claimed that Dr. Luke offered to release her from her contract in exchange for recanting her accusations, Kesha wrote: "I would rather let the truth ruin my career than lie for a monster ever again." Since coming forward, Kesha has never wavered in her story. But at some point, she realized she had to make a choice.

"I have a lot of beautiful nights. And then, I have nights where I sit up crying to myself because I have built up resentment," she says. "But I want to cope with that. I don't want to let it destroy me."

Kesha's turned the page, but she's no sucker. When I ask what she'd tell someone who wanted to be the next generation's Kesha, she laughs dryly. "I would say, get a fucking amazing lawyer. And learn from my mistakes."

Photography: Oscar Ouk

Styling: Christopher Horan

Makeup and Hair: Vittorio Masecchia at Opus Beauty using Kesha Rose Beauty and Number 4 Hair Care

Nails: Miho Okawara