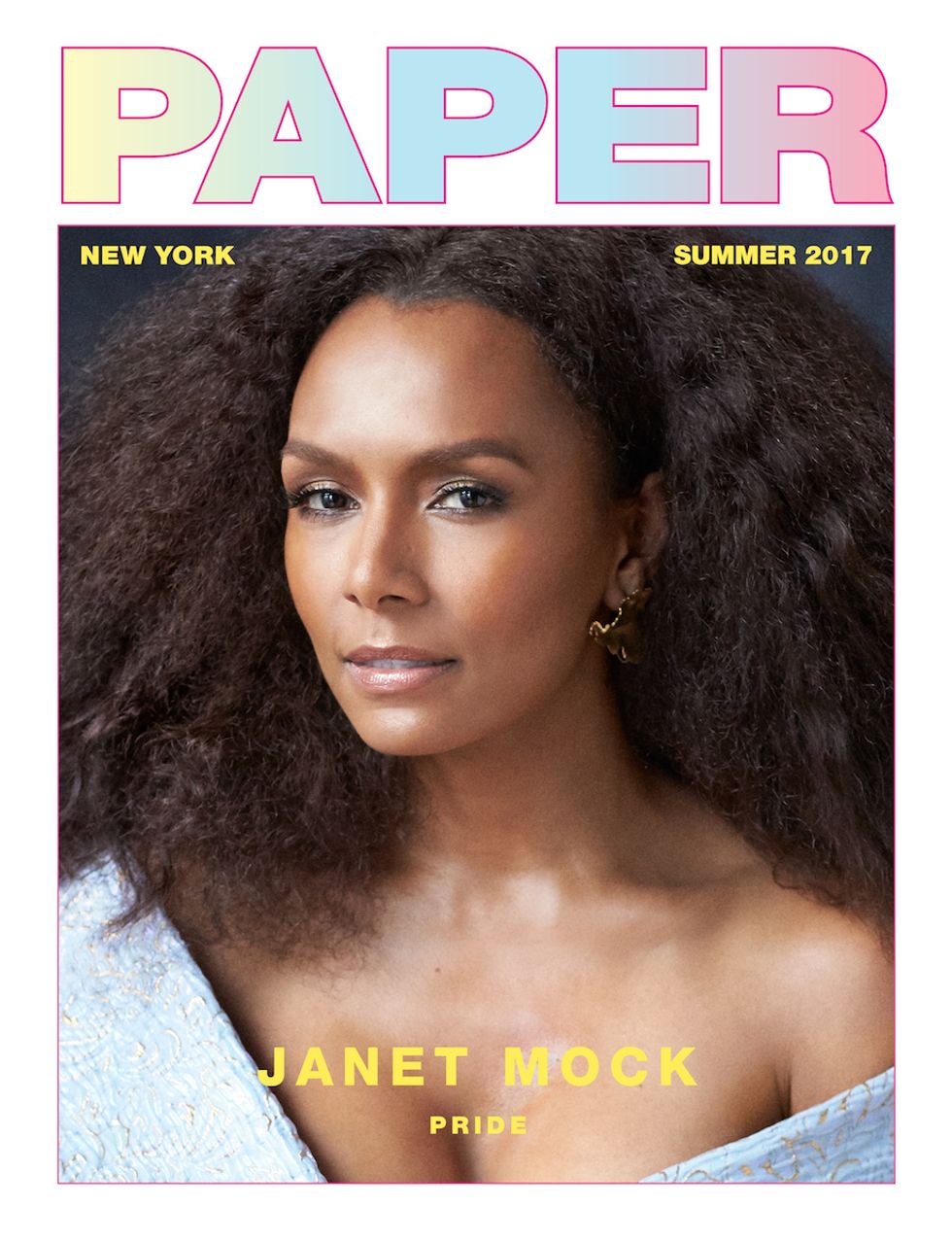

Join us at PAPER in June and July as we celebrate Pride online with a series of digital-only covers, features, and galleries celebrating and supporting the diversity, beauty, resiliency, and humor of the LGBTQ community. For our second digital cover, we spoke with the multihyphenate activist Janet Mock about her speech at the Women's March on Washington, the importance of intersectionality, and embracing both Audre Lorde and Amber Rose.

On January 21st, a day after Donald Trump's inauguration as the 45th president of the United States, the mood throughout much if not most of the country was somber. Women, people of color, and LGBTQ communities in all fifty states wondered what the new administration, with its talk of "Making America Great Again," would mean for them.

In Washington, D.C., though, the capital was alive with activity. Half a million people took buses, trains, and planes to join the Women's March on Washington, the largest single-day protest in U.S. history. Even in the gray winter air, the feeling was jubilant, the signs were clever, and the hats were pink.

The throngs of marchers spread out across the National Mall, while the voices of celebrities like Madonna, Scarlett Johansson, and America Ferrera boomed from the loudspeakers onstage.

Author and trans activist Janet Mock was one of thirteen women on the policy committee for the march, having helped build its guiding principles and vision. Mock was the reason that sex workers were included in the march's platform and one of two trans persons in the day's long lineup of speakers (the other was Raquel Willis, who Mock has mentored). Taking the stage after Planned Parenthood president Cecile Richards, Mock gave a moving speech that quickly went viral. Mock said she realized, looking out over a sea of pink pussy hats, that she was likely largely speaking to people who were engaging in their very first political act. "This was the first time that they were outraged," she told me. "I have been outraged about injustice my entire life."

The audience's political inexperience made Mock's speech all the more important, she said. When she addressed the crowd, she made sure to include the trans women that she felt might otherwise not be covered under the movement's umbrella:

"I stand here today most of all because I am my sister's keeper. My sisters and siblings are being beaten and brutalized, neglected, and invisibilizied, extinguished and exiled. My sisters and siblings have been pushed out of hostile homes and intolerant schools. My sisters and siblings have been forced into detention facilities and prisons and deeper into poverty. And I hold these harsh truths close. They enrage me and fuel me. But I cannot survive on righteous anger alone. Today, by being here, it is my commitment to getting us free that keeps me marching."

Mock has been using her unique story to communicate universal truths since becoming a public figure. In 2011, after five years as a pop culture editor at People, Mock came out as one of the first publicly trans journalists in an as-told-to piece in Marie Claire.

Since then, she's published a best-selling memoir, hosted a pop culture show on MSNBC, launched a podcast, Never Before, joined Allure as a contributing editor and has a second memoir, Surpassing Certainty: What My Twenties Taught Me, out June 13.

"It was vitally important for me to tell my story," Mock said of recording her life. "When I was growing up, there were no references for me that felt positive or aspirational in any sense."

From #OscarsSoWhite to the whitewashing of Asian characters in Hollywood, the predictable cycle of outrage followed by vows to "do better" often end with little provable gains in representation. Though shows like Jill Soloway's Transparent and the ubiquity of stars like Caitlyn Jenner and Laverne Cox help promote trans visibility, Mock points out that even those narratives can be lacking in the nuance that represents actual human experience.

"Trans stories have been told, at least in American media, since at least the 1960s, but they all were older, usually white transitioning folk," she said. "Those are important narratives to tell, but there were none that were rooted in my generation, who were able to live their truth at younger ages." It was that gap, she explained, "of not having that on bookshelves or represented in media," that compelled her to share her experiences.

Mock, now 34, says that the path to self-realization wasn't something she completed overnight. "It wasn't like, I'm going tell my story, and then boom, I'm in the New York Times and I'm talking to the world."

In her first memoir, Redefining Realness, Mock charts her childhood and adolescence in Hawaii—a state she describes as more accepting of trans-ness than other places in the U.S., though not without its prejudices. She began medically transitioning as a teenager, paid for by her stint as a sex worker, and credits her mother for giving her a refuge at home by "staying out of the way." "She may not have had the answers," Mock explained, "but she never projected her fears on to me. She just let me be."

Mock knows that having a parent who was not actively involved in, but at least not disparaging of her transition is rare. "I'm very conscious that a lot of young people don't have that," she said. "All they are surrounded with are hostile spaces, at school, at home, and then on the street. So it was also about trying to highlight a life where I was vulnerable, but also resourceful. None of us are just one thing. We are multiplicities."

Mock is also keenly aware that young trans kids lack mentors and role models, she says, because they so frequently ask her for guidance and information. "Surpassing Certainty largely came out of conversations that I had with younger people who reach out to me when I go to their college campuses or through my Tumblr messages or DMs, asking me questions about 'how do I live in this body and this identity?' Things like, 'I'm in college now, how do I bring my full self to the workplace, how do I bring my full self to my resume, how do I talk about or is my identity even important when it comes to trying to get a job?'"

Where her first memoir dealt with her early adolescence, Surpassing Certainty focuses on Mock's life as young woman of color (at this point assumed by most in her life to be a cisgender female), marrying her first husband at 21 and climbing the corporate media ladder in New York City. It also deals with those questions young people so often approach Mock with—how and when to disclose trans-ness to partners and friends; how to navigate largely white workplaces as a young person of color; what to do when others may not realize that they are crossing your boundaries (but they are). In Surpassing Certainty, Mock lays bare experiences — both painful and triumphant — and translates them into lessons that are neither trite nor condescending, but as real, complex and messy as life itself.

As a trained journalist, Mock's interests aren't restricted to her own story. She lit up when discussing her new ten-episode podcast, Never Before, that was executive produced by Lena Dunham and made in collaboration with Lenny Letter.

Flashing her brilliantly white smile, Mock proudly announced that her podcast's first guest was Miss Tina Lawson-Knowles. "I interviewed her in her home in the Hollywood Hills. I cried during that episode. She was the creative force behind Destiny's Child, and we talked about how, being the only black girl in my school, seeing a positive, glamorous, empowering image of young black girlhood take up space on one of my favorite shows, TRL, was so vital to me."

"The podcast is largely about me sharing space and centering culture," Mock continued. "But then also centering my personal experiences and interviewing a lot of the people that were pivotal to my own becoming, and to just sit and, as we say in Hawaii, 'talk story.'" She noted many of her guests "likely have never shared quality space and time with a person like me, whatever that means. So it's about that sharing, and the exchange that happens in those conversations.

It's her expert storytelling and navigation of complex topics that make Mock such an appealing figure. When things happen in the trans community, she is often the one people turn to for advice, for input, for a soundbite. In the past, she's expressed discomfort with being labeled a trans advocate, telling the New York Times last month that placing one person at the forefront of a movement can "flatten everyone else's experience and turn us into a monolith." She also cites this as the reason she's on Twitter less and less these days, admitting she's "tired of having to discuss the slices of trauma in our life that oftentimes outweigh some of the triumphs that we do accomplish." Just as it did at the March, though, her voice serves not only as a lifeline to young people but as a powerful megaphone for the experiences of a group that is often misunderstood or rendered completely invisible.

Earlier this year, Dave Chappelle and novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche were criticized for their separate comments on the trans community. Chappelle joked in a comedy special that trans people are behind black people in the "Oppression Olympics" and need to, essentially, wait their turn. In an interview about feminism with the UK's Channel 4, Adiche commented that trans women grow up with male privilege (while cisgender women don't).

Mock acknowledges that both lines of logic are faulty, and expressed disappointment that sometimes the black community doesn't see the work that black transgender people do. "We've been activating around our blackness for a long time," she said. "We're part of the Black Lives Matter movement, we're doing this work, but rarely are we ever centered," she said, adding that three of BLM's founders are queer black women. Her best guess is that when prominent black figures like Chappelle say things like "wait your turn," they're likely "not even thinking about the possibility that there's black trans folk."

"They're thinking of the most visible portraits of trans-ness, which are older, white wealthy trans folk who have access to protect themselves on a mountain in Malibu or in a mansion in Chicago. They're not [thinking of] the girls on the streets or the subways, the girls on the streets who have to hype themselves up every single day to be like, 'Can I go outside to go work at Jamba Juice?'"

The public outcry against Adiche in particular was fierce. While a backlash in favor of trans people seems like progress, Mock pointed out that the targets of such heavy criticism are often treated differently by their race.

"White women have been saying transphobic shit for so long, and they never get called out the way Chimamanda was called out," she said. "There was a rallying cry to take her off her pedestal. It's this constant narrative that black people are more—more homophobic, transphobic, non-accepting, etcetera. It gets churned out the same way even in LGBTQ spaces where white cis gay men rule. They run most of the organizations and have control of most of the resources, and they can be misogynistic and sexist and racist and classist and transphobic as hell, but no one's calling them out as much as they would call out a black cis gender body that says something remotely problematic. It's complicated, and it's tough. Because these are my people, too."

When circled back to the Women's March, Mock conceded that criticisms that event was too white and cis-centered were "completely valid," adding "there probably was more diversity on stage in the plethora of speakers than there was for folks in the audience." She also acknowledged that the very intersectionality at the heart of her activism is a concept not everyone has fully grasped yet.

"A lot of the most difficult part of my work is not so much about talking to 'the other side.' It's about talking to people who think they're woke or conscious, and talking to liberals who are sometimes really basic in the way in which they do the work. It's getting through to the people who are trying to do right, the well-intentioned who aren't really there yet. That's the challenge of a writer who writes in this space. Language, as bell hooks said, is a place of struggle. And so we have to use what we have, which is our words, to communicate feelings, and nuance, and complication."

"Another part of my work," she continued, "is challenging respectability politics, which say that sex workers, dancers, trans women and folk who are 'thotting around town' are not important and vital to our movement. Just as much as we talk about Gloria Steinem and bell hooks and Barbara Smith and Audre Lorde, we also need to be talking about Cardi B, Amber Rose, and Blac Chyna. Women who are out there hustling in a world that wants to silence and shame them every single day are vital and important. We need to free ourselves from saying that the only people worthy of our protection and resources are those who are respectable, virtuous, and easily contained."

Hair: Charlie Taylor

Makeup: Wendi Miyake

Stylist Assistants: Sara Clemens, Julie Gray

From Your Site Articles