Andy Warhol's Trans Subjects Finally Get Named

By Elizabeth Hoover

Aug 24, 2018

Pop art pioneer Andy Warhol famously created portraits of some of the biggest celebrities in American history: Marylyn Monroe, Elvis, Liz Taylor. But his largest body of work is a rarely exhibited and lesser-known series of anonymous drag queens and transgender women of color called Ladies and Gentlemen.

Italian art dealer Luciano Anselmino commissioned the series in 1974, paying Warhol $900,000 for 105 canvases. It was Warhol's most lucrative commission. The commission documents reveal purulent voyeurism and distain, requesting "impersonal and anonymous" subjects to capture "the transvestite," as if each sitter represented the same static identity as the next. Anselmino choose the title as a joke.

But Warhol flaunted the spirit of the commission with exuberant portraits showing individuals in strikingly theatrical and playful poses, each embodying their own version of feminine glamour. Working with obsessive speed, Warhol took more than 500 Polaroids of 19 sitters and produced 268 canvases, more than doubling the request. Yet, he paid each sitter only $50 per session, and, when he exhibited the work in Italy in 1975, didn't include their names.

The catalogue of the 1975 show describes the sitters as having "the grimace of the victim," but curator Jessica Beck sees strength and joy. "The sitters are feminine, strong, and beautiful," she says. "The series is about drag culture, which was led by African American and Latina transwomen, though the history comes out as very white."

Beck is curating an installation of 40 works from and archival material related to Ladies and Gentlemen that will be on view October 13, 2018-March 17, 2019 at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. This time, the subjects have names — thanks to meticulous research undertaken by the Andy Warhol Foundation in New York.

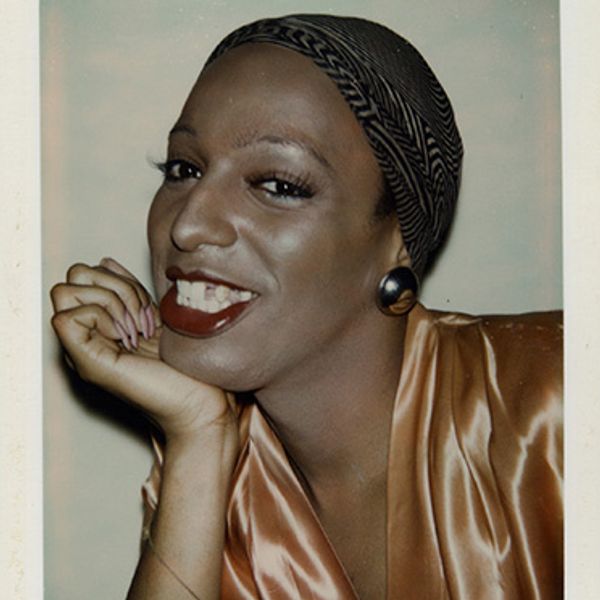

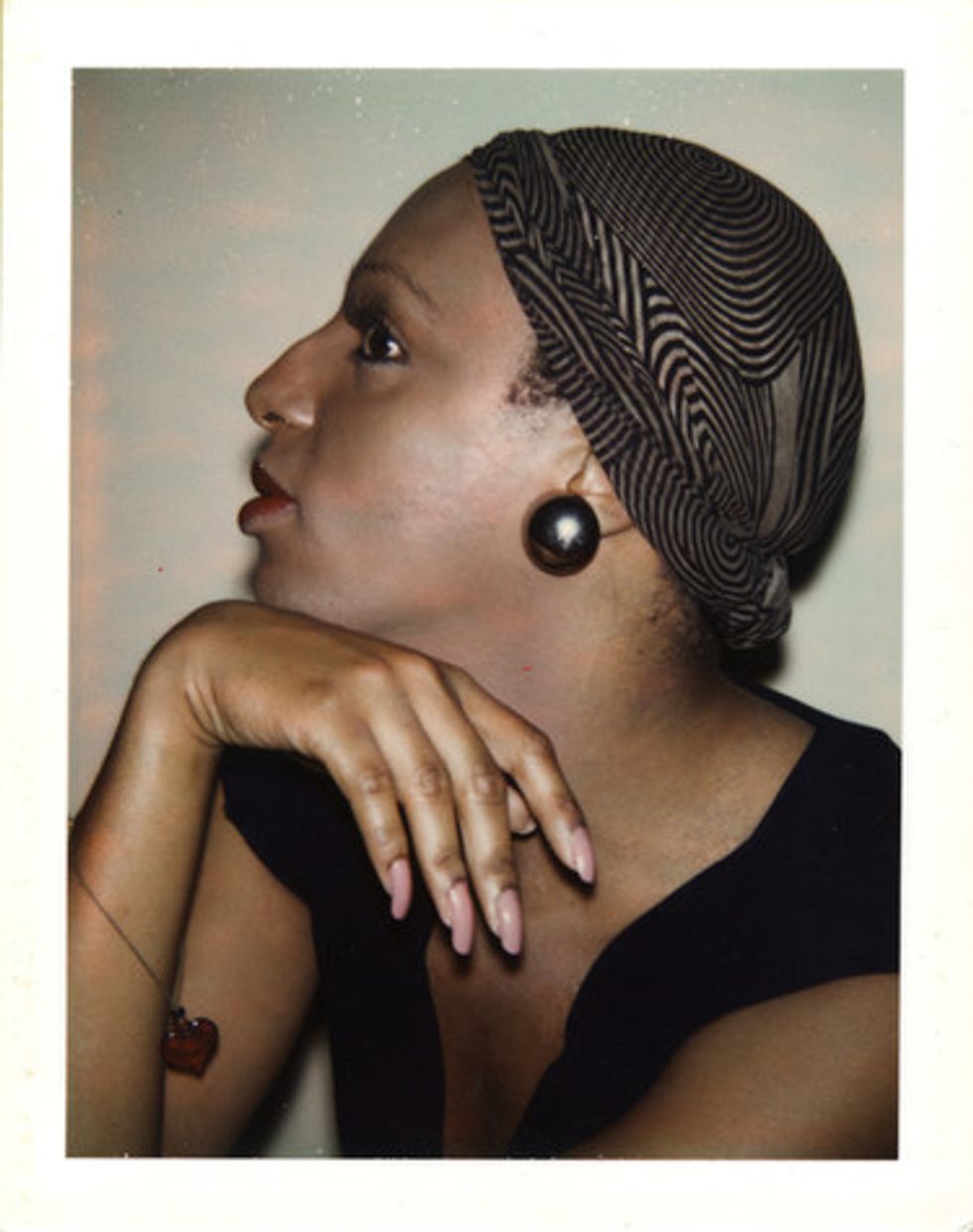

Andy Warhol, Wilhelmina Ross, 1974, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Ladies and Gentlemen is being shown in conjunction with Cry, Baby, a solo show by contemporary artist Devan Shimoyama. In his colorful and glittering paintings of African American boys and men coiled with snakes or crying crystal tears, Beck saw echoes of Warhol's little-known series. In both, she sees "the possibility of embracing one's beauty and accepting one's queerness."

Currently, Shimoyama is painting his own series of drag queens of color, one of which will be inserted into the Ladies and Gentlemen installation. "Drag queens have superheroic tendencies," he says. "They wear spandex, have alter egos, do their duty out of necessity for the greater good (giving the gays a space and secret coded language). They're fully realizing a fictitious illusion of their own creation."

Andy Warhol, Wilhelmina Ross, 1974, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

That illusion includes more than swapping genders. While RuPaul's Drag Race is bringing drag to a wider audience, it only shows a tiny sliver of the wild gender play that happens in drag culture. (Judge Michelle Visage's documented hatred of "boy drag" erases the contributions of both drag kings and drag performers who disregard the gender binary). Drag creatively mixes gender markers, as well as satirizes race and class. This has roots in the balls of the 1970s and 80s depicted in Jennie Livingston's 1991 documentary Paris is Burning and now in FX's Pose. They included categories based on performing whiteness and upper-class status, as well as gender-based "realness." For participants who wanted to be seen as women in and out of the balls, mistakes or flaws might mean being harassed or even killed. The practice of "reading," or critiquing each look, could save a person's life by pointing out what they needed to correct before hitting the streets.

Andy Warhol, Ladies and Gentlemen (Wilhelmina Ross), 1975, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

It's impossible to discern how all the sitters in Ladies and Gentlemen identified in terms of their gender, but in the paintings they are all flawlessly feminine. "He painted them like he did all of his portraits: as icons," Beck explains. Meanwhile the Polaroids reveal marks of economic struggle: cheap costume jewelry, ill-fitting wigs, missing teeth. At the Warhol Museum, visitors will be able to view the Polaroids on an iPad in the gallery.

The tension between the Polaroids and the final portraits tells a poignant story of the disconnect between desire and reality. However, queer culture adeptly converts tragedy into camp by coopting and parodying mainstream ideals that violently reject queerness. Warhol's technique of screen printing with deliberately misaligned pigments and layers of paint spilling outside the lines captures the theatricality of drag.

In one image, a sitter wears a garish blonde wig with ponytails. She smiles broadly at the viewer, letting them in on a joke about the artificiality of white beauty standards. That sitter is activist Marsha P. Johnson, famous for setting off the 1968 Stonewall Riots. Johnson co-founded of STAR (Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries), a support organization for homeless queer people with a name connecting performance and revolutionary politics.

"Each sitter in Ladies and Gentlemen is an individual, striking, and interesting human being," says Neil Printz of the Andy Warhol Foundation. "They had difficult lives, but were amazingly creative and brilliantly, wildly funny." As the editor of Warhol's catalogue raisonné, Printz worked with researchers to cull though canceled checks, release forms, and first-hand accounts to attach names to each likeness in a volume published in 2014.

Andy Warhol, Wilhelmina Ross, 1974, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

The researchers were aided by chance encounters. In 1997 the Gagosian Gallery in New York exhibited a portion of Ladies and Gentlemen, and the Warhol Foundation received a call from Jimmy Camicia, founder of the radical underground drag theater The Hot Peaches. He recognized one of his performers, Wilhemina Ross. Of all the sitters, Warhol seemed most taken with her, snapping 52 Polaroids and producing 73 paintings. In them, she is luminous, beaming at the viewer with an open gaze, her hand elegantly draped over her head or around her neck.

"The commission was for anonymous sitters, but Warhol was not responding that way," Printz says. "He had a personal response to each and asked them to sign the Polaroids; by doing that he helped retrieve their identities."

Related | Remembering Marsha P. Johnson

"My reading is that this commission inspired Warhol," Beck says, noting Warhol appeared in drag in his own work after completing Ladies and Gentlemen. "He is part of the story." Exactly what part Warhol played is hard to parse because he has always been a bit of a cipher — projecting disaffected cool, but then writing with scholarly precision about drag's "ambulatory archive."

"Something I really stand by is that queerness is a constant state of flux," Shimoyama says. "It is magic." Taken together Ladies and Gentlemen doesn't depict "the transvestite," instead shows queerness' magical flux in portraits of remarkable individuals who are finally being recognized by name.

Devan Shimoyama's Cry, Baby will be on display from October 13, 2018–March 17, 2019. The Ladies and Gentlemen series is a rotation of the permanent collection. Please contact the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for more information and tickets.

From Your Site Articles

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October