Matthew McConaughey Found His Rhythm

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

We’re at a bar in Downtown, New York City and Matthew McConaughey has my phone. He is sending my mother a voice memo.

“Jennifer! Matthew McConaughey here, talking to your daughter Joan,” he says in his signature Southern drawl “I got to talk to your daughter for quite some time about things, and my movies and books, and it was an awesome talk. I haven't even read it yet, and I'm already saying, good job! I think she's doing the right thing.”

A week prior, untethered from step-and-repeats and family and onlooking paparazzi, McConaughey is similarly unpredictable in our conversation. We jump from high concept metaphors about the weather — “Create your own weather, then blow in wind” — to politics and anecdotes about Richard Linklater’s on-set habits. Wrangling him feels a bit like the bull riding synonymous with his home state of Texas; this is a man weathered by the changing seasons and tempered by decades in Hollywood’s singular spotlight.

Fresh off a years-long hiatus from on screen acting, McConaughey returned to the silver screen earlier this year in The Rivals of Amziah King, bookending the festival circuit in September with The Lost Bus, adapted from a true story about the 2018 Northern California Camp Fire and co-starring America Ferrera. “What I remembered is how much I enjoyed acting, and how much acting actually felt like a vacation, because it was a singular obsession,” he tells me.

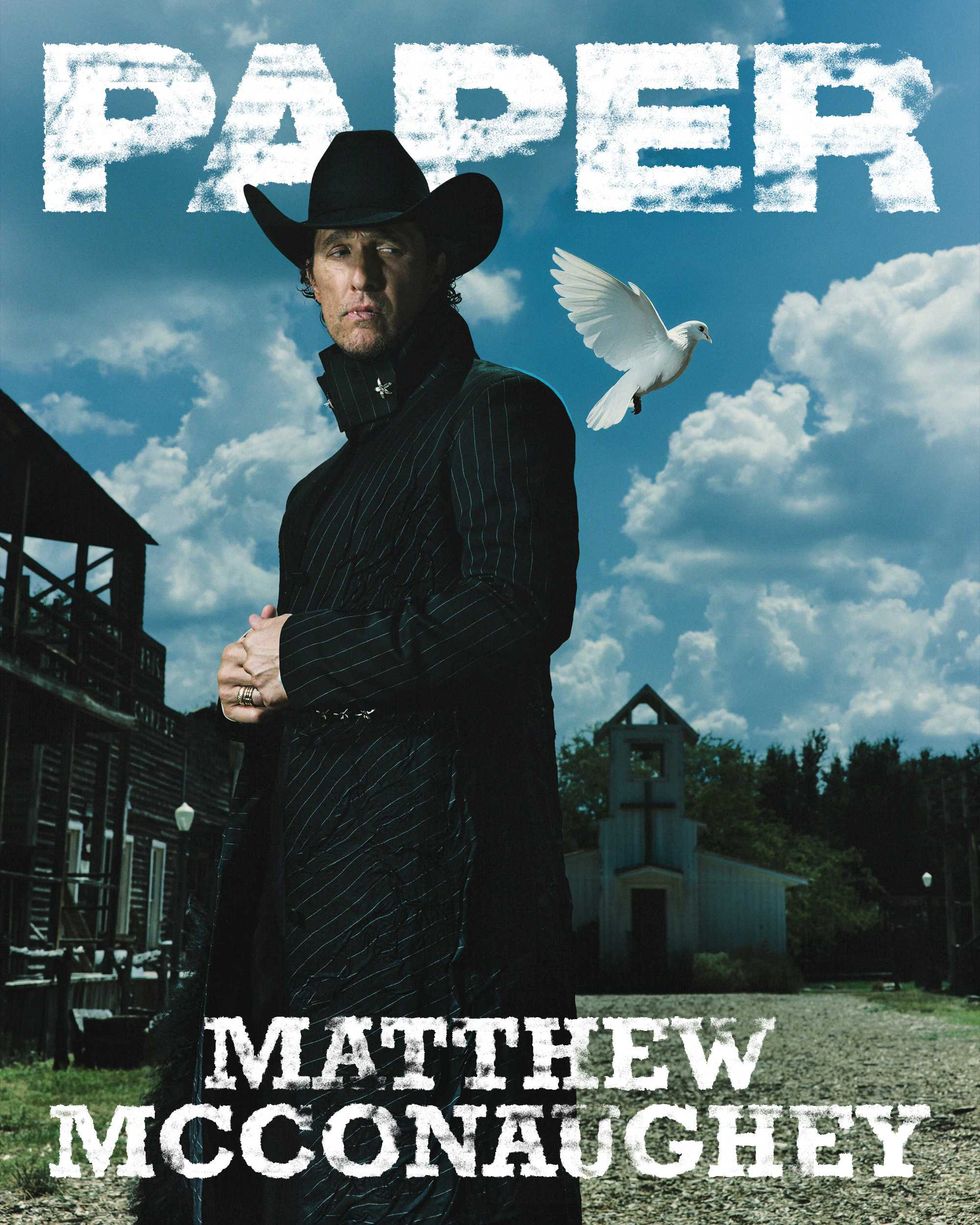

Coat and Shirt: Campillo, Pants: Giorgio Armani, Boots: Dsquared2, Rings: Grown Brilliance & Talent’s Own, Hat: Stetson

In the “six, seven years” in between, McCaughney has “taken on a few new challenges, like the writing.” In that time he published his bestselling memoir, Greenlights, and a children’s book, Just Because. He also deepened his relationship to music and poetry through his upcoming follow-up to Greenlights, Poems & Prayers. “I'm a guy who always starts with logic. Always have, and I've had to flip the script with this one, because that's what I'm having the most fun writing.”

For McConaughey, “on Saturday night, having a great time with my wife, sipping on my second tequila,” he finds himself returning to the rhymes that make up his book. “Forget academia, forget the damn logic. Forget acing the test. Let's slide into this rhyme.”

The rhythm has followed him his whole career, even from his melodic first words onscreen — “Alright, alright, alright,” in that aforementioned Linklater flick. “I always take some drums or conga on set and into my trailer. With The Wolf of Wall Street, I banged my chest. That's something I'll do before scenes all the time.” As he tells it, “We just happened to put that in that scene because Leonardo was like, What are you doing before this scene? I said, ‘Well, I'm just kind of getting out of my head and finding a rhythm.’”

When we talk about acting, he jokes that it is like a vacation, and I see him slip into platitudes and anecdotes about the press, the festival circuit, talk shows and movie trivia. When I ask about writing though, he lights up, leans forward, emits a disarming intensity. “A lot of the different poems in my book, I woke up in the middle of the night with a meter. I got up and walked to go find my pen and paper, and kept it in my mind. It's like staying in a dream, right?” he says. “The rhythm of a dream.” From that dream followed “hundreds —all right, twenties — of pages” of Poems & Prayers. “I’d go back and go, ‘Boy, was any of that any good?’”

Back at New York Fashion Week, I watch him slip into that sing-song Southern drawal for my mom a thousand miles away while his publicist hides behind her hands, clearly accustomed to this. I’m reminded of an earlier adage from our conversation. Acting is a vacation and “sports is more of a discipline,” but for McConaughey, “Music is the freedom, the dream. I let my freak flag fly.”

For more on The Lost Bus, Poems & Prayers, and that Richard Linklater anecdote, read PAPER’s full interview with Matthew McConaughey below. (This interview has been edited and condensed.)

How are you doing after the Toronto International Film Festival? Obviously, you're coming off of The Lost Bus premiere there.

TIFF was fun. Look, I haven't done that in seven, eight years, so it was fun to go do the press and the carpet and the 1000 cameras. Plus, I got to do it with my mom and my son who was there. It wasn't my mom's first time, it was my son's first time. So the fact that it was a family affair just made the whole thing.

I wanted to ask you about that, because you took a hiatus from on screen acting, and you made your return earlier this year with The Rivals of Amziah King, and now you're back with The Lost Bus. How has it been jumping back into the swing of it as an actor? z

I've learned over the years that it's another part to play. You get to get into that zone when you're doing the making of the movies. What I remembered is how much I enjoyed acting, and how much acting actually felt like a vacation, because it was a singular obsession. And over the last six, seven years, I've taken on a few new challenges, like the writing, and had to compartmentalize. When we went back to acting, it's like, whoop! That's it. Take care of mine and be obsessed with that character. That's it. I don't have to look over my shoulder for anything else; that felt like a vacation. Now you get to the press and stuff — I've learned over the years that I get into another zone. I'm in the “yes zone,” meaning I want to arrive on time. I want to be on time everywhere, but never rush. And I get into a zone and I cruise, and I am, if you ask anybody I run into if they're, hey, will you do this? I want to be affirmative.

I always repeat this, but one of the coolest and simplest things I heard early on. I was on The Jay Leno Show, my first talk show. He comes by the green room. He goes, “You nervous?” I go, “Yeah, a little bit.” He goes, “Look, I got simple advice, how to make this work.” I go what? He goes, “Just want to be here.” It's always stuck with me: You just want to be there. All of a sudden the clock goes faster. You look back, you enjoy what you did more.What movie were you promoting on the Jay Leno Show?

Newton Boys!

When you are talking about the singular obsession that is acting — you're also coming into the release of your next book, Poems and Prayers. Do you find that singular obsession translates into the writing, or do you go to a separate place as a writer than the place that you're going to creatively as an actor?

I'm very hermetical, if that's a word. I become a hermit when I write. I go away to write. I need probably, at least, eight days of runway. Just go on my own clock. Forget sundown, sunrise, everything, just when I feel it. In that way it is singular, but I have to control my environment. It’s not singular in that when I'm writing, I'm subjectively becoming each one of the characters I'm writing. I'm clicking into each one. I'm writing as I'm going, I'm having a dialog, Socratic dialog, with myself, playing that character as I remember him, or how I'm creating him.

Acting is just one character. Boom, three months, singular obsession, reverence for the craft, head down. Let's turn up another rock. Let's look at this scene from a different viewpoint. I never get tired of that. I'm convinced that if that is my singular obsession when I'm making a film, if that's all I really worry about, and all I'm concerned about, that’s time well spent.

So much of acting is a dialogue with other actors, with the director, with the writers. But writing is such a singular activity. Where do you then get that creativity in writing, if you're not having, let's say, a whole team of people around you on a set to bounce ideas off of?

As I write, every day, on my phone, I pop it in notes. Last night, I probably had four notes. I'll hit two or three or four notes on this things, pop in a line, something somebody said, something I heard, a malapropism, a diddy. I was saying to the dogs, they were double dipped on breakfast, and it ended up rhyming. I'm going to write that little thing down, maybe that's a lyric. And then I'll come back at the end of the month, or two months, or when I go to write, and I'll pull all of those out and have a look at them. So my launch pad lines are already there for the theme or for the song, for the diddy or for the poem or for the prayer.

I'm not starting from a blank page, with a blank theme. Oh, I'll look, and here's what I’ve been thinking about, here's what's been on my mind, here's what I’ve been hearing.. For Poems & Prayers, it was basically the last three years I really started to lean into the poems and prayers and rhymes and lyrics and ideals of life, instead of the logic of life. I'm a guy who always starts with logic. Always have, and I've had to flip the script with this one, because that's what I'm having the most fun writing. That's what, on Saturday night, having a great time with my wife, sipping on my second tequila, that's where my mind goes. It's rhyming. So forget academia, forget the damn logic. Forget acing the test. Let's slide into this rhyme. I was finding more reason in the rhyme, instead of rhyme out of the reason, which is usually my go to state.

Has rhyming been something that has followed you your whole life? Is that something, even as a kid or as a young actor, you found yourself doing?

Musicality has always been a gateway to imagination. Sports have been: here's how you prepare. I can do sports analogies forever. On Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, he handed every character a cassette tape, and he goes, “This is what I think your character's been listening to.”

I love this anecdote.

You're 19 years old, and the director gives you a tape with some badass ‘70s rock and roll on it, and just says, “Oh, I think you would be listening to this.” That's my homework, but also, that doesn’t tell Matthew what to do. That just frames a world. It frames the movement.

I always take some drums or conga on set and into my trailer. With The Wolf of Wall Street, I banged my chest. That's something I'll do before scenes all the time. We just happened to put that in that scene because Leonardo was like, What are you doing before this scene? I said, Well, I'm just kind of getting out of my head and finding a rhythm.

A way to break into the character, or break out of Matthew.

I was nervous! I'm working on my first Scorsese film. I got a big scene that I'm shooting. It's not a get in the head thing, but getting out of the head. It also lowers the voice. It also makes a lot of people in the crew go, “What's up with the weirdo?” Which I like, because I know that now I'm the underdog and I gotta come out of this. It paints myself a bit in the corner as the odd person, which is a fun place to put yourself in as a performer.

A lot of the different poems in my book, I woke up in the middle of the night with a meter. I got up and walked to go find my pen and paper, and kept it in my mind. It's like staying in a dream, right? The rhythm of a dream. And then I just started writing. It would be one line, and I’d find its meter. And if I found that meter, then I’d write hundreds — all right, twenties — of pages, and I’d go back and go, “Boy, was any of that any good?” If I'm going to start a story, if I can get the first line just right in the pocket, “Oh, that's it. That's got the swing to it from the hip.” The rest of the story just kind of writes itself, and it’s musical.

I was thinking about your staying power as a leading man in Hollywood. It does come from this feeling that everyone is doing the Hollywood thing, and you're just slightly out of step with the rest of the machine — it’s interesting to hear you talk about blending sports and music into your creativity.

I mean, sports is more of a discipline; music is the freedom, the dream. I let my freak flag fly. With work or life, even relationships and fatherhood — these are not political terms, but I've always looked at them as conservative early, liberal late. Let's learn our foundation here. There are some rules, you know? There are some guidelines, there is a border. Let's understand the rules. I think I wrote this in Greenlights: create your own weather, then blow in wind. But if you look around, you go, Okay, I'm gonna get in the sandbox. Well, hang on a second. Let me walk through that thing. Make sure there's no broken glass and stuff. Yeah? And if there's not, well, it's fine to get naked and do back flips in the damn thing.

Coat and Shirt: Campillo, Pants: Giorgio Armani, Boots: Dsquared2, Ring: Grown Brilliance & Talent’s Own, Hat: Stetson

In the intervening years, since you took a break from acting, Texas has become such a focal point culturally in this country, whether it's musically, whether it's in art, books, movies, politically. What's a misconception people might have about Texas?

I’d say Texas is more wide open and unregulated upon ‘howdy,’ but if you screw up, the consequences can be worse on ‘goodbye.’ It's free enterprise on the way in. But if you get out of line, the consequences can be harsher on the on goodbye. The politics definitely lean to the conservative side, but Texas’s brand, Texas’s spirit, is independence. I don't want us to forget that. Pull your boots up, be self reliant. We do have that identity that I think the rest of the United States sees, and the rest of the world sees. For instance, when I was an exchange student and I was meeting with hundreds of other exchange students from all around the world, every one of them was like, “Well, I'm from Stockholm, Sweden.” I would just go, “I'm from Texas,” and everyone knew. I didn't have to say United States, just Texas. As far as misconceptions, it is still a very hospitable state, it is a very welcoming state. And probably more open armed to more diversity than people might think.

I don't even know if ironic is the word, but you leave Hollywood, and then, in recent years, Hollywood has not necessarily followed you specifically, but followed you on the trail to Texas. You leave the system and then the system puts on a cowboy hat and follows you here.

Taylor Sherridan’s Yellowstone helped with that. Even though they're Montana, the cowboy hat and open spaces is probably the most iconic image that represents Texas. So maybe that, along with Texas being such a pro-business state. Still to this day, people go, “Oh, you're from Texas, so you live on a ranch, you ride a horse. Where's your hat?” I'm like, I don't live on a ranch. There are ranches everywhere. I don't, and I'm a decent horse rider, but not a great one, and don't ride one every day.” But I haven't thought about that.

You call the book tour your “revival” tour. What was something that was revived in you during the process of writing this book?

I think part of the reason I naturally found myself, for the last two years, writing more poems and prayers, was to counter the amount of cynicism I was starting to feel. To counter looking around at the world or listening to the news and going, “I ain't gonna chance it. I don't believe in them. I ain't trusting them. Let me just take care of mine. Got my family. Let me put up the walls and just take care of mine, because the world's gone whack.”

I started not giving people the benefit of the doubt, stereotyping, objectifying people. That's a bit of a disease. It started to creep into my mind. What really scared me was when I started to go, “Okay, so that's just how it is.” That's when I went, “Whoa, wait a minute, buddy. We swore that we would never let the cynical disease creep in.” I think that’s one of the worst diseases that we choose to allow ourselves to get. And it happens with age. I get it. We go from being innocent, being born to naive, and we are just ignorant of certain things. And then we learn some more, and we get skeptical and discerning and discriminate and make choices and judgments. But don't go further, because the next step is that cynicism. We're witty at the party. We get to laugh. But cynicism is for quitters, and I don't want to quit. It's easy to become a cynic. It's clever, like I said, it gets the joke. It gets the laugh at the cocktail hour.

It's the easy punch line to look at the world and be like, “Look at this thing we all see, huh?”

Yeah, it's easy, and I think it's a way to get sick. I think writing Poems & Prayers was a reaction to myself going, “Hey, man, I gotta stave this off.” Let's look up. Let's dream. Let's think of some ideals. Let's give more importance to what your kids are saying when they're just innocently doing something. It's a spiritual therapy for me. Personally, I hope it's something that can revive others as well, in that way. But it's personal for me, and it's some of the work I need to do, because I've been dealing with too much. I've been letting myself fall prey to too much doubt.

You’ve spoken quite publicly about being profoundly changed by the Uvalde school shooting. You’ve stepped into advocacy and activism in the intervening years since people have seen you properly on screen. You write the book in the midst of it. It's easy to be cynical, and you made this other choice, to say something, to get involved, to feel like you had some participation in it. How has your creative work, coming back to the grind of Hollywood, and the grind of writing and promoting, been changed by the experience of that event and the years since?

Good question, one I haven't really thought of, but is obviously true. That has affected me and will continue to. It's sobering, and that's part of it, if you go engage in some of those hard things. It’s ugly. I'm on the periphery of it, coming in as, hopefully, a helpful voice. That’s probably where some of the cynicism comes from. I say in the book, about how I'm not ready to say: “Oh, this is just how it is.” With the shooting in Uvalde, there were more before, and there have been more since, and there will be more. But to sit there and go, “Well, hey, this is how it is.” That's quitting.

Look, when I say it's sobering… dealing with Uvalde, or the Greenlights Grant Initiative, I didn't come back and think small talk is absolutely mendacious. ‘Fuck you talking about weather? Hey! Shit’s going on in the world.’ But I never want to let a sense of humor go. And a sense of humor can help us through. And sure has helped me with going, “Okay, how do we untie the knot here?” Humor doesn't mean that I'm not giving the crisis credit. It just means it can help me deal with it, and hopefully help us deal with it, whether that was talking with the families, whether that's the aftermath of coming home and being overly self serious with the kids, or calling out any silly behavior

I don't know exactly how it has affected my creativity, but do I go back and do something like The Lost Bus, to maybe have more of an interest and an understanding of what it would mean and what it would cost, and how painful it would be to be a no show Dad? To be someone who, every time times got rough, or you need to be responsible, to go, I'm out the back door. That is what this guy in my portrayal does. I know a lot of people, a lot of middle aged men, who are walking around in circles now, because they looked up and they were like, “Oh shit, this is not where I thought I'd be.” I failed my way to my 50s and I got nothing to show for it. How much of that is because they didn't put in the smart hustle to get what they wanted, and how much of that is the American Dream is just blurrier than ever?

It's easy to see events and experience events like Uvalde, something that's so common now, and feel a cynicism, feel a hopelessness. “Wasn't there anything we could do? Why couldn't it have gone a different way?” Then you see a story like the one portrayed in The Lost Bus, about people who made a difficult choice, and were heroes in the moment. I don't know, maybe it's those stories we have to hold on to when faced with cynicism.

I don't know, if subconsciously, that’s a reason why Kevin and The Lost Bus appealed to me. Probably subconsciously, because I was around some of those events. People are always talking about what's the definition of a hero? I don't know. It does seem consistent, though, that people who have heroic acts go towards a crisis instead of away from it. You have first responders who are heroic in the fact that they're called on when there is a crisis. Then you have people like Mary and Kevin, who don’t go out to be a hero. They're a teacher and a bus driver, and they happen to be the person in the place, in the time, and they had to make the call, yeah? On a very basic level, they just went: “I'll go pick up the kids, or I'll take the kids on the bus, because it's my job.” They weren't going, “Oh yeah, it'll be heroic.”

I enjoyed wondering about this for my portrayal of Kevin. How much of that decision to go get the kids instead of going home to get mom and son, how much of that was a sneaking, mystical sense that this could be his salvation? I know I've done that before.

Leather Coat & Shirt: Tom Ford, Pants: KidSuper, Boots: Dsquared2, Sunglasses: Jacques Marie Mage, Pocketwatch: Bulova

Story: Joan Summers

Photography: Greg Swales

Styling: Angelina Cantu

Groomer: Kara Yoshimoto Bua

Photo assistant: Justin D. Heron

Styling assistants: Joyce Esquenazi Mitrani, Quinn Tommy Herbert, Sal Lee

Digi-tech: Ish Holmes

Gaffer: Dé Randle

Local production: SUNFALL

Production assistant: Nyres Colbert

Chief Creative Officer: Brian Calle

Executive Creative Producer: Angelina Cantu

Entertainment Editor: Joan Summers

Music Editor: Erica Campbell

Graphic Design: Jewel Baek

Location: Buggy Barn Museum