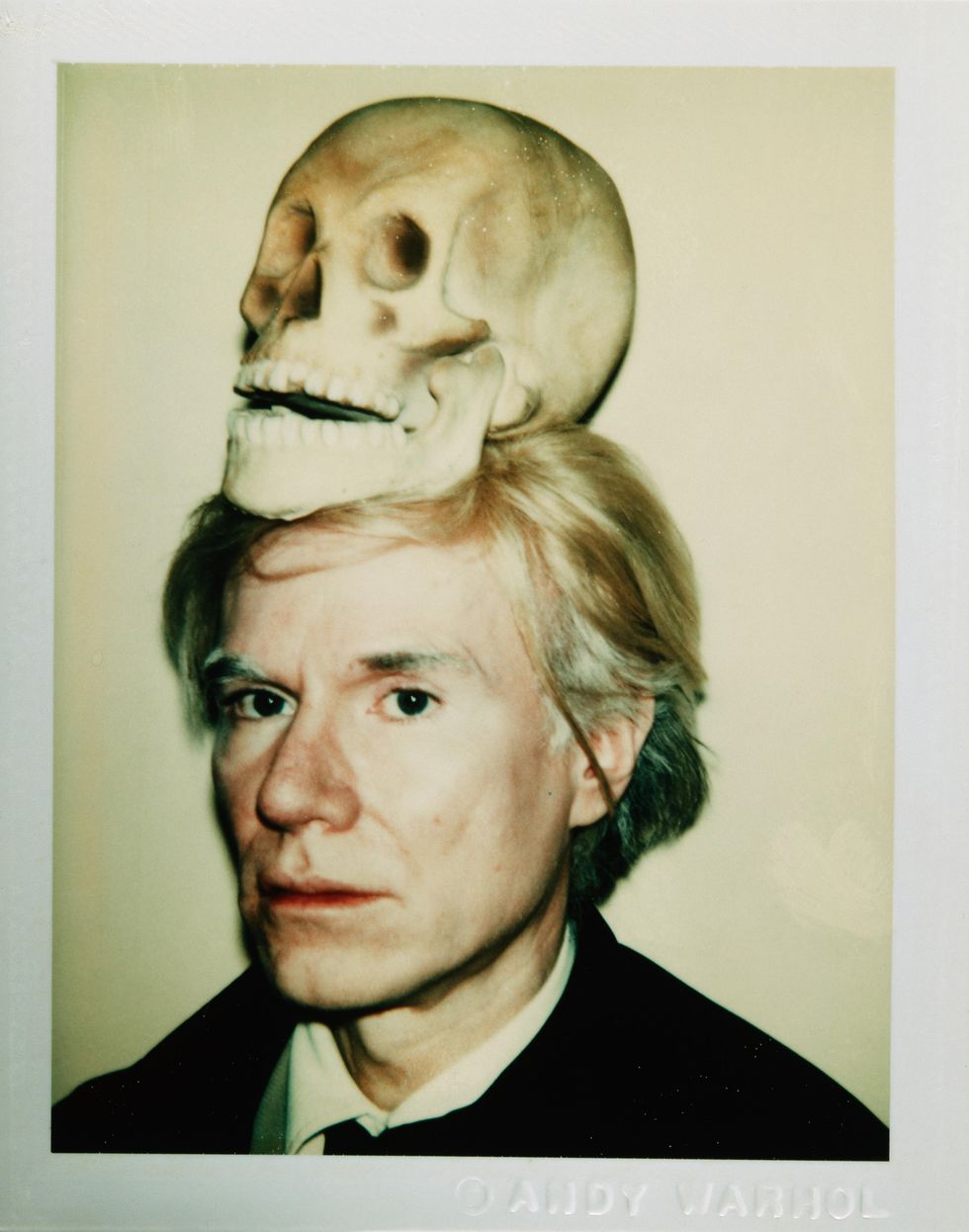

Andy Warhol’s legacy could be defined by extreme superficiality, much by his own design, that reduces all complexities and overrides his personal experiences. That is, ultimately, what the late pop artist would’ve wanted: for the general public to think only of his multi-colored Marilyn Monroe prints as symbols of consumerism, no soul. He wanted to become a machine — to get repeated to the point of total ubiquity, and there’s no room for the real Andrew Warhol, a working class Pittsburgh native, inside such a fast-paced, fame-obsessed operation.

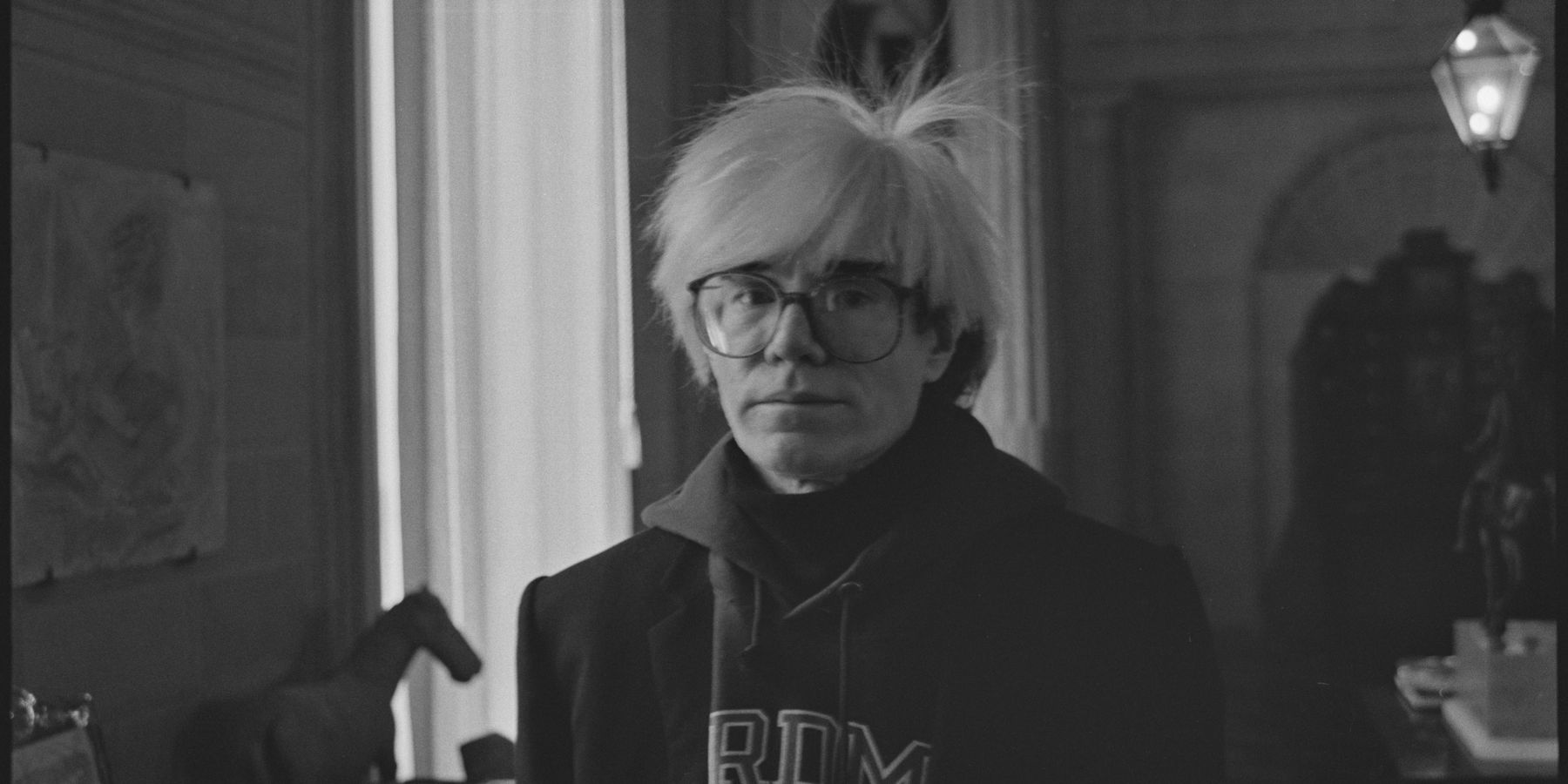

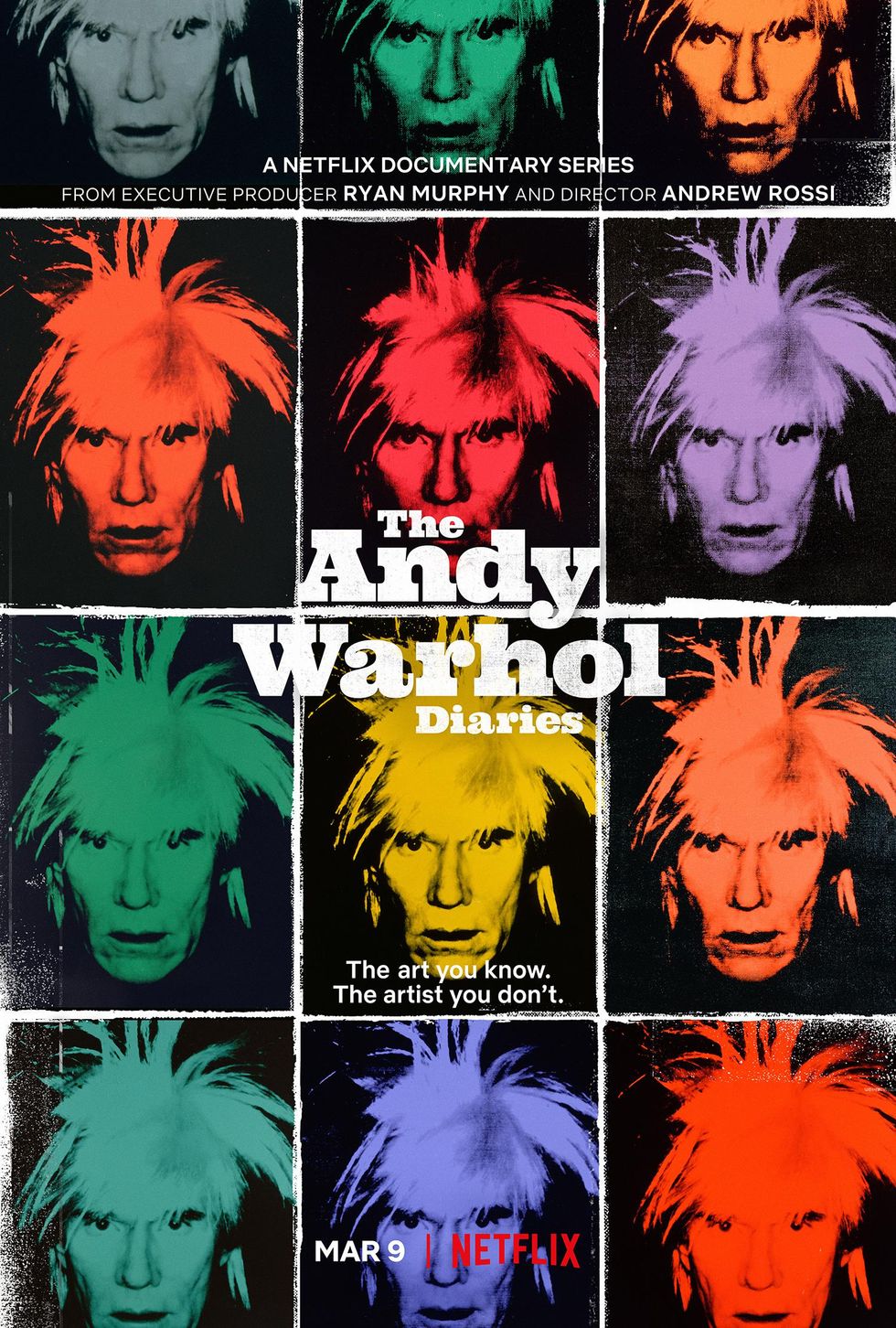

In The Andy Warhol Diaries, a new Netflix series executive produced by Ryan Murphy and directed by Andrew Rossi, the icon’s two dimensions get knocked into a million different parts — all the intimate anecdotes, difficult memories or blunt insecurities that Warhol chronicled in his memoir, published posthumously in 1989. Unlike popular depictions, this compelling six-part portrait zeroes in on Warhol’s personal relationships and the way those evolved alongside his practice.

Underneath the silver wig and emotionless, canned quotes (“Uh yes, uh no”) was a queer man grappling with his own sexuality, and a deep desire for connection and validation. Yes, Warhol chased the magical chaos of downtown bohemia and Studio 54 glamour across NYC, but he also wanted the comfort of love — companionship that was perhaps more settled than anything he could offer a partner. He tried nonetheless, tentatively diving into relationships (all questionably platonic) that helped Warhol dance with a life he never fully locked down.

Although many people came and went from Warhol’s orbit, Rossi zeroed in on three formative subjects. First, Jed Johnson, the young interior designer who stumbled into The Factory one day and would become Warhol’s first live-in friend before the two parted ways in a tumultuous breakup. Then, Jean-Michel Basquiat, the radical, young painter whom Warhol closely collaborated with during a time when his career had plateaued. And, most importantly, Jon Gould, the handsome Paramount Pictures executive that Warhol dated for years until the man’s death in 1986.

Through all these entries, as underscored in The Andy Warhol Diaries, details of Warhol’s relationships were unclear — not only because of his own self-doubt, but as a result of the larger homophobic climate that kept so many LGBTQ people from freely coming out. This was heightened by the AIDS epidemic, and its sweeping culture of fear and confusion, that made queer folks afraid of being themselves publicly and documenting same-sex intimacy. Although Gould loved Warhol, he made the artist promise to not put anything personal about him in the diary.

Ahead of The Andy Warhol Diaries’ official Netflix premiere on March 9, PAPER talked with Andrew Rossi about "the art you know, the artist you don't," below.

Compared to so many depictions of Andy Warhol’s life that we’ve seen, this series really focuses on his love life — or lack thereof. He’s described as “sexless” by some and as “lonely” by others. For you, why was this an important topic to explore?

I think Andy Warhol is always seen as hidden, as robotic, as somebody who doesn’t have something behind a public performance or a mask that he presents to the world, and the key to understanding him was really, for me, his romantic desire that comes through so powerfully in the diaries. He talks about the meaning of life, and that he’s empty and he wants to fall in love as a solution to that feeling. In his pursuit of Jon Gould, in his relationship with Jed Johnson, I think you find the truth that Andy was holding behind the mask.

Why do you think that topic has been largely untapped up until now?

I think there has been homophobia, of course, in society, and even in art history perhaps, and even internalized homophobia that Andy experienced and existed in his circle of family and friends at The Factory. This is a very vigorous conversation that I tried to pursue along with Bob Colacello, Christopher Makos and others who knew Andy. He presented this performance as an armor to protect himself against a lifestyle and identity that when he was born in 1928, and certainly when he was growing up in Pittsburgh, was illegal, and in the ’70s and ’80s, was very difficult for him to live as an out gay man among the high society people he was trying to sell his paintings to and get portrait commissions from. This has been erased from the record and I think the series is a powerful effort to bring it back.

"[Andy Warhol] created work that communicates a queer longing that I think in some ways is an effort to figure out how you fit in society."

Andy wrote in his diary, “People’s fantasies are what give them problems.” For him, fantasies were a double-edged sword because without them he wouldn’t be Andy Warhol, but he was always struggling with his fantasies. After now completing this series, do you think Andy would look back and think everything he did was worth the sacrifice?

I think Andy believed in hard work and in some form of self-sacrifice. I do believe that that was part of his Byzantine Catholic identification. He created work that communicates a queer longing that I think in some ways is an effort to figure out how you fit in society. I think the diaries also show that voice of wanting to belong and so, this idea that there were fantasies that could get him into trouble definitely comes through as you reference, at the end of Episode 1, when he’s trying to have a long term relationship with Jed Johnson, his domestic partner. At that time, the idea of two men being together in a committed relationship was bizarre. It existed, but it was rare and Andy was struggling to figure out how he could stay with Jed. This fantasy of Studio 54 and all of the men he met when he was doing the Sex Parts polaroids, all of those were things he wanted to pursue, so he sacrificed his love with Jed and a longterm relationship to pursue those aspirations.

Andy had such incredible knack for adapting and slipping into new generations, which not a lot of artists have been able to do. People often say, “Andy would have loved this generation,” but we also find through watching this series that he had some insecurities about too much exposure, about public opinion, like when he was nervous that his company was going to get this big profile or appearing on SNL. So how do you think he would actually navigate the world of social media and virality, knowing all of those complexities?

I think Andy is a construction on every level. He reinvented himself when he took the A off of his last name, Warhola, and put on the white wig. He was so meticulous about what he presented, and I think the opportunity that social media presents to become an avatar and reinvent oneself would be appealing, but he would pursue it with a lot of caution. He had been burned many times throughout his life and that’s also what I wanted to show. When he first came into the art world, he brought these boy drawings to the Tanager Gallery that were rejected. They were seen as not art because they depicted homoerotic love. He was malign when he did the celebrity portraits and, as he says when he had the Shadows opening, Rene Ricard described it as “disco decor” when in fact it was the real him, and it was avant-garde and no one understood it. I think he would tread lightly into social media, but also see that it really brings to life his prediction that in the future everyone would be famous for 15 minutes and could reinvent themselves.

In the section where Andy’s heralded as a great example of artists as art, Jeffrey Deitch said TikTok stars are “degraded versions” of artists as art. How do you think Andy would have reacted to that point of view? Especially on TikTok, sameness and repetition make people successful and that’s very pop, which is something Andy championed.

I think the idea of your personal brand also being your commercial identity, and fusing those two, making your public performance and who you represent, part of your creative forcefield, that is something Jay-Z has done and Kanye West, both of whom cite Andy as a role model, and they build multi-platform businesses taking whatever they represent as individuals and putting that into media. TikTok stars are doing that, but on a much smaller scale, in their bedrooms or out on the street dancing, and there is something about who they appear as and their vibe that comes through and gives them a presence. It’s not as sophisticated or multi-media as what Andy was doing with Warhol Enterprises, but it is the seed of the idea.

There's a special moment where Andy finally decides that he’s comfortable dancing. Why was it important to zero in on that as a climax and what do you think it represented for Andy as a turning point or personal awakening?

I really wanted to show that Andy found in Jon Gould some outlet for his personal expression of joy, and a way to let go of some of his guardedness and his armor. I think that’s a beautiful moment that also relates to his dance diagram paintings, and it shows you how some of his artwork is about trying to follow a manual to become something and to lose yourself. In that moment he realizes that Jon [Gould] is this companion who can bring him into a world like Studio 54, or any other venue, where he can dance, and just like the preppy handbook is another kind of instruction manual on how to pass, dancing becomes something he can pursue to be happy.

"I think there’s a cliché on some levels that Andy [Warhol] was a monster, or that he manipulated people."

One of the ongoing arguments surrounding Andy Warhol’s work is whether he exploited his subjects or celebrated them. This is discussed a lot, especially in relation to the Ladies and Gentlemen series, which feels particularly relevant to conversations happening in the trans community today. Where do you stand on the nuanced debate?

I think there’s a cliché on some levels that Andy was a monster, or that he manipulated people. He’s certainly not perfect, he’s not a saint, but there is in my view, sometimes a failure to understand what was behind his fear and his relationships with others in The Factory in particular. As Julian Schnabel says, he gave people the outlet to be who they wanted to be, he gave permission, which is a form of license that has along with it sometimes not a lot of guardrails, so he could be certainly selfish, I think that's clear, but I also think he had a lot of affection for the people in his life. Among the revelations that come out when I spoke to Jay Gould, Jon Gould’s twin brother, is that Andy went to the hospital, which was a place that he was terrified of after he was shot in 1968, and stayed with Jon for three weeks every night to nurse him back to health when he was first diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. Certainly then he went back to Cedars-Sinai Hospital later, but Andy sacrificed his own sense of security to be there with Jon, so there are other examples that counter the myth of him as the manipulative monster, and I think everyone has a textured place in this world and it’s important to understand both sides of Andy.

As a director, why was Andy Warhol’s story, and this series in particular, important for you?

I started making The Andy Warhol Diaries 11 years ago. I had just finished a film, Page One: A Year Inside the New York Times, and my agent, Josh Braun, asked me what’s next. I’ve always looked in my work to try and tackle icons, or big subjects and institutions that loom large in our imaginations but we don’t understand on a human level, and I immediately thought that Andy Warhol would be somebody that I would like to understand better and go behind the mask and humanize. It’s a way for me as a bisexual man growing up in the ’80s in a very homophobic world, I found Andy always to be a safe space, a hero, somebody who had courage to be a queer person and to navigate a really choppy world. I wanted to understand how he did that and what was the truth that he was protecting, and the diaries became this incredible road map to that.

Photos courtesy of Netflix

From Your Site Articles

- "The Andy Warhol Diaries" Spotlights His Queer Love Story - PAPER ›

- Polaroid Legend Maripol and Kelly Cutrone on Andy Warhol - PAPER ›

- Andy Cohen as Andy Warhol - PAPER ›

- A Supreme Court Case Over An Andy Warhol Painting Could End Fair Use ›

- Ryan Pfluger Talks New Art Book 'Holding Space' ›

Related Articles Around the Web