Saving New York, One Skate Spot at a Time

Story by Anna Grace Lee & Nicole Oliveira / Photography by Sophie DayJul 16, 2019

It's a long-told horror story: New York is dead. You know how the rest goes. The city's boring, it's lost its sense of humor, it's too stressful, it just isn't cool. Everyone loves to lament the loss of old New York, and sometimes it feels like we'll never be able to revive it. So when the chance comes along to salvage a small piece of the good old days, we have to jump on it. The latest in city spaces caught in the war between old and new? Lower Manhattan's Tompkins Square Park.

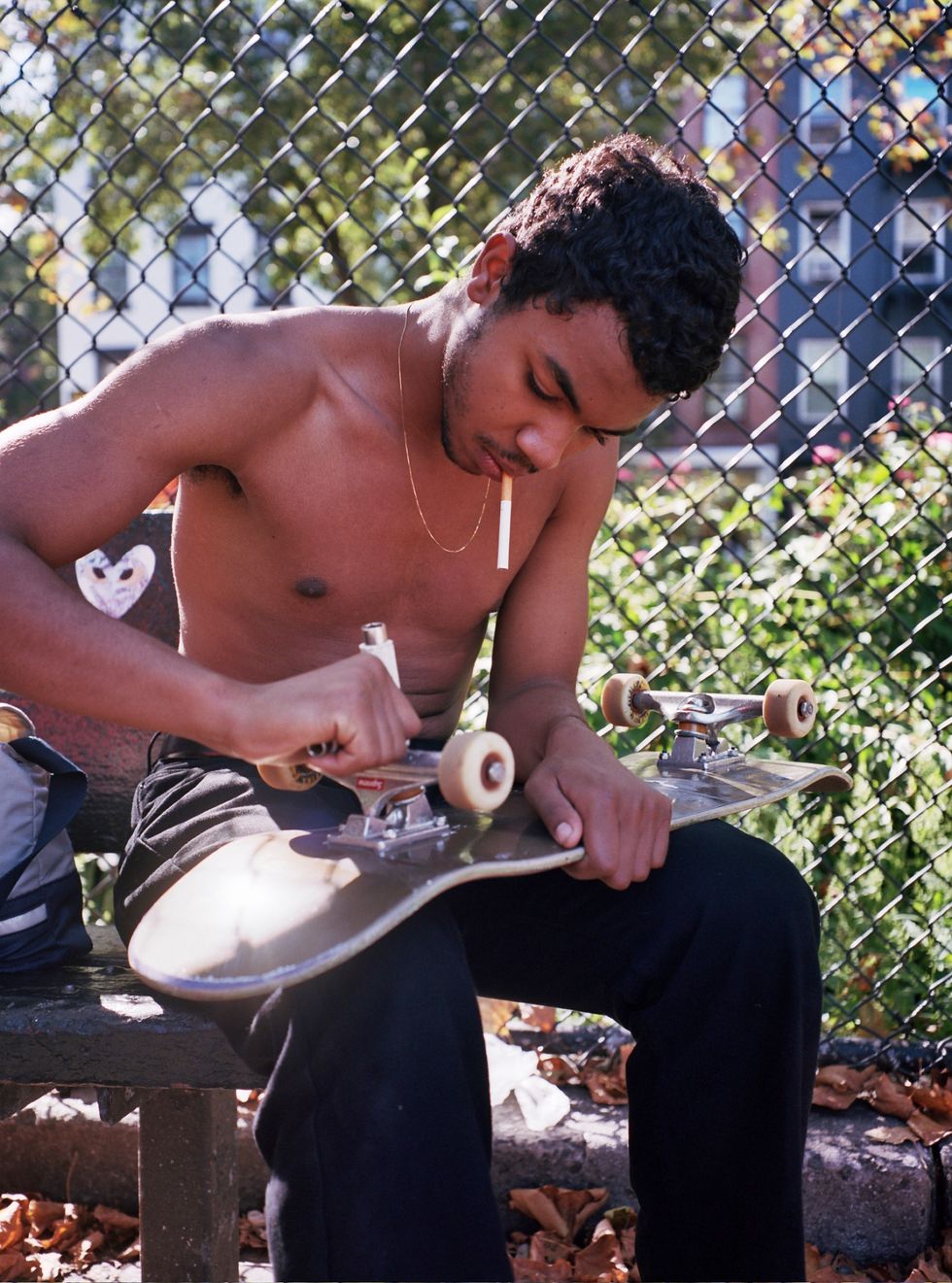

There's a strangely calming cacophony in Tompkins Square, the sounds of people in the East Village park going about their days — playing chess, smoking cigarettes, twirling ribbons, lounging in the grass. All kinds of people come and go, but you can always count on seeing skateboarders. No matter the weather, they're always there.

The skaters may be the underlying melody keeping the park in tune: the sound of wheels rolling on the asphalt, of tricks attempted, failed, then finally landed. Lose the tune and the spirit of skateboarders, and the symbiosis of the park just might fall apart — grow eerily, sadly silent, fallen prey to corporate softball games and tepid picnic lunches.

Skaters are all over the park and in the East Village neighborhood, but they mainly congregate in the northwest corner of Tompkins Square, known as the TF, or "Training Facility" because of the approachability and versatility it offers to first-time skaters. The TF is the only spot in the neighborhood that provides flat, open ground and the space to learn the sport, which will make its Olympic debut at the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.

Now, the New York City skateboarding community and their allies are rallying to "Save Tompkins" after the City's Department of Parks and Recreation approved a proposal to replace the asphalt at the training facility with synthetic turf in 2020. The Parks Department's decision was made in order to accommodate those who would normally use the fields at the East River Park, which is set to undergo a $1.45 billion flood-protection plan that will take more than three years.

Synthetic turf, the skaters argue, would render the TF un-skateable and therefore exclude an entire group of people who make up the great majority of park users. Local skateboarder Adam Zhu started an online petition to express to the Parks Department just how important of a space it is, not only for skaters, but for a larger community of people whose activities rely on the asphalt there. At time of writing, the petition has more than 24,000 signatures, including that of notable East Village lover, Chloë Sevigny — who told AM New York that Tompkins Square Park is one of the only places left in New York that is "still really real."

This is not the first time Tompkins Square has been a site of unrest within the East Village community. The relatively small (10.5 acre) park has seen numerous demonstrations and riots dating as far back as the 1800s, many in response to forces of gentrification in the area. Next month will mark the 31st anniversary of the Tompkins Square Riot in which squatters, the neighborhood's homeless, and community organizers rebelled against the Parks Department's attempt to enforce a 1 AM curfew for the park. Intended to "curb disorder," the responses to the curfew were stronger than some expected. For those who frequented the park religiously, free access wasn't a privilege, but a right — one they were willing to fight for. Clayton Patterson, photographer, videographer, and Godfather of the East Village, remarked that the "road to the police state" began the night of the Tompkins Square Riot. After "endless protests [and] hundreds of arrests," the police learned to control the streets, Patterson said.

Patterson was right in more ways than one. His video documentation of the riot opened the public's eyes to excessive use of force and police brutality against some of the East Village's most vulnerable. A New York Times article published a week after the events at Tompkins claims that the "scenes of violence seemed all the more surreal because of their rarity on such a scale in the city." Though a protest of this scale may not seem so unusual in an era where marches for women's rights, environmental protections, and queer liberation are so frequently in the public eye, the world was a different place 30 years ago. The Lower East Side was known as a haven for artists and other eclectic personalities, but it was also subject to increased police surveillance under the Koch administration, primarily in response to the drug use that occurred in the park. The government did, at times, go to extremes to address social and political issues around the city.

When asked what the neighborhood was like back in the '80s and '90s, comic artist and author of War in the Neighborhood, Seth Tobocman, said the city failed to maintain the area or support it with the proper infrastructure. There was a sense, he explained, that nothing was being done by the government, leading community members to take matters into their own hands. Therefore, while the LES is more often recognized for fostering a "counter-cultural youth movement," as Tobocman put it, it's important to remember its legacy as a civically-minded community.

Since the Parks' turf proposal became public knowledge, there have been a few comparisons made between the riot of '88 and the struggle today. Steve Rodriguez, unofficial mayor of New York City skateboarding and founder of skateboard company 5BORO NYC, told PAPER: "I think it's a completely different situation, but it definitely brings up those memories because that did happen." He continued, remarking on the way in which New Yorkers often remember extreme situations when similar events happen again. Is history repeating itself? Not entirely, but we can't (and shouldn't) forget the past. Rodriguez said, "For people that grew up around Tompkins Square in the East Village during that time period, the police riots in the '80s are so ingrained in their memories."

Despite the neighborhood changes, it seems the locals remain tight knit. Even earlier this year when the Parks Department scrapped its remodel for East River Park — deciding to bury it under a landfill— people spoke out in defense of the local ecosystem. Many residents and community leaders were outraged, considering the East Village has had to say goodbye to several virtually historic landmarks. In 2019 alone, both St. Mark's Comics and Moishe's Bake Shop, closed after 30 years of serving the community due to the steady gentrification of lower Manhattan. With the local landscape having changed so much, some feel the neighborhood they called home growing up, isn't the same East Village today. Chloë Sevigny, once an East Village queen, told the Daily Beast, "walking around the East Village, I just want to cry at the state of it. There are so many fuckin' jocks everywhere! It's like a frat house everywhere... I don't know if it's a sign of the times, but where are the real weirdos? The real outcasts? They're a vanishing breed here. Maybe New York isn't drawing that anymore because it's too expensive."

In Zhu's opinion, the park is one of the few parts of the neighborhood that has remained untouched. "Tompkins Square is the last cornerstone of the identity of the East Village," he said. Throw in some astroturf and he thinks the neighborhood will be fully gentrified. To Zhu and skaters alike, the park is where many of them got their start. It's a place where they can be their most unadulterated selves and where many have gathered after a rough day at school since they were kids. Sophie Day, 21-year-old photographer and friend of many of the TF skaters, explained: "You can see kids younger than 10 years old starting to skate in the park alongside the older kids. You can see old friends meeting up in the park, and people coming for the first time." For Day, every time she meets friends at TF she's "thankful that [we] all have this special place to go."

The "Save Tompkins" movement may have been jump-started by skaters, but it's about more than skateboarding, Zhu said. It's about "preserving the identity of the neighborhood," and resisting what the city calls "beautification," which locals know is just another way of saying "gentrification." As is typical of urban renewal projects (another fancy term for gentrification), newcomers may not know the history of a community, leaving OG's feeling like the changes unfolding right outside their doors are not happening with them in mind. If the history of the LES says anything it's that folks are more than willing to fight for what they believe in and in this case, that means protecting the park.

For Steve Rodriguez, much of the issue with the synthetic turf proposal is the inter-generational importance of the space. "Beyond skateboarding, for me, it's the cultural significance of that place. I skateboarded there in the '80s. I skateboarded there in the '90s, in the 2000s... It's someplace that is multigenerational. My son can skate there. It's a place where people go to learn, where it's a safe place, and multi-use. You have people kicking soccer balls, you have people learning how to ride their bike, skateboarding, roller skating, rollerblading, scootering." He pointed out that for children growing up in the East Village whose parents want to keep them close, the TF is really the only place they have access to open space to learn to skate.

Amid the uproar over possible astroturf and an end to skating at Tompkins, Crystal Howard, Assistant Commissioner for Communications to the Parks Department, released a statement on her personal Instagram on July 2nd. In it, she explained the City's motivations for pursuing the proposed changes. Replacing the asphalt with synthetic turf, she stated, is part of a larger effort to provide more green space for the community. Though the Department claims the "decision wasn't made lightly," many were unsatisfied with this response, and took to social media to share their stories to #savetompkins. In response, the Parks contacted key leaders in the area to get their input.

Ralph Musolino, Deputy Chief of Operations for Manhattan parks, reached out to Rodriguez two weeks ago to connect him with Sarah Neilson, Chief of Policy and Long-Range Planning for Parks, to begin the process of working with the skateboarding community to resolve the issue. Rodriguez has worked with Musolino "for at least 20 years" and said that "in reference to skateboarding in New York City, [Musolino] has always worked with the community to at least try and have the best resolution for the end users of parks. He is amazing, and he has gone out of his way." Rodriguez himself has served as a pro bono skateboard consultant for Parks before, playing an integral role in the establishment of the reworked Brooklyn Banks in 2005, which revived the historical skate spot as an official skatepark for a time before being closed for construction.

A meeting to discuss the Tompkins Square turf proposal was held on Tuesday, July 9th. Along with a representative from Quartersnacks, a website dedicated to NYC skateboarding founded in 2005, a team of people from many end user groups of the asphalt area in Tompkins Square Park were invited to attend the meeting. Rodriguez said the meeting was "kind of like an open forum where everybody said what their affiliation is, where they live, how they are involved with Tompkins. There were skateboarders, there were non-skateboarders, there were professional skateboarders, there were Olympian skateboarders." They did not come to a final decision on the fate of the asphalt, but Rodriguez felt it "was a very positive first meeting." He added, "I really want to thank the Parks Department for listening. Specifically, Sarah Neilson and Bill Castro. I do want to thank them for listening to the community because I know that them knowing will only help the situation." He remains realistic, however: "There's many other layers of people involved in this. [Castro] has to navigate that so that everybody's happy or everybody is a little bit not happy and then there's a solution."

Rodriguez is optimistic that they will be able to come to a compromise with the Parks department. "Parks always says, 'It's your park. You should take care of them. You should be involved.' That's what these people are doing. They had an experience there. They want to make sure that future generations can have that same experience."

How to Help:

Photography: Sophie Day