The Still Life: NYC's Buzziest Art Shows This Month

By Harry Tafoya

Jul 29, 2024Like music, fashion and publishing, summertime is usually a period of relative hibernation for the art world before it strikes again with a vengeance in September. The conventional wisdom is that those who can afford to, immediately jet off to a luxurious elsewhere, while leaving reduced hours behind and months-worth of leftovers to hang up on the wall. But if this is a relatively low-stakes moment for buyers and sellers, the same is absolutely not true for the viewer. Summer happens to be when galleries are most inclined to take risks on artists who’ve never been shown and to give curators carte blanche to go nuts with their programming. Like a vintage store, cast-off odds and ends can be better than the heavily advertised, overpriced junk in the window. It’s all available for you to take in, even if only to duck in for the air conditioning. Here’s what I saw...

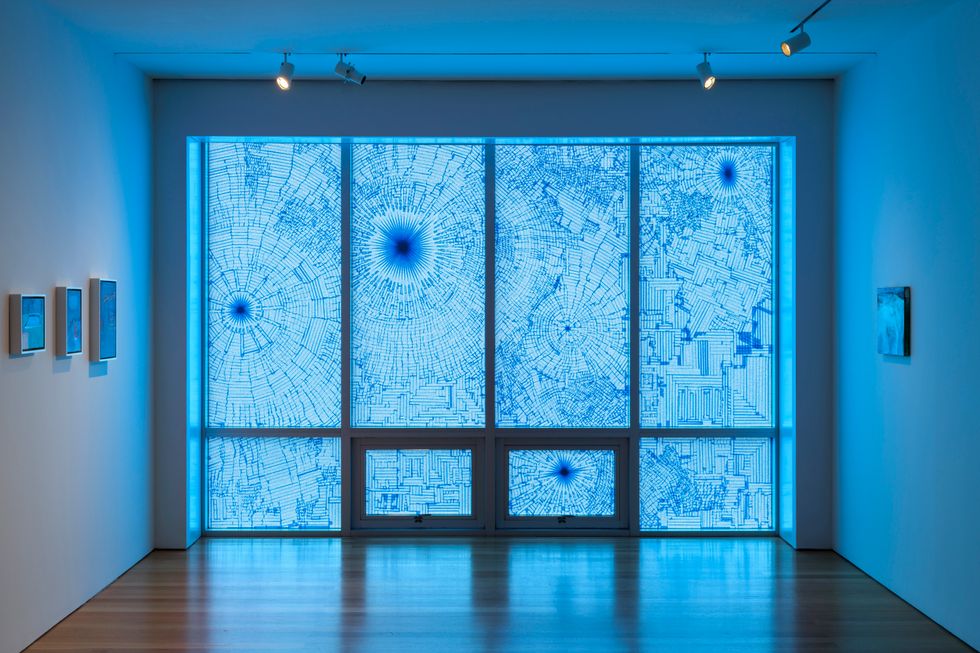

"The Swimmer" - curated by Jonathan Rider - FLAG Art Foundation

It often feels like you have to be Annabelle Bronstein to find a decent pool to lounge by this time of year. But for anyone who doesn’t have an “in” at Soho House or the will to book it all the way out to Connecticut or Fire Island, The Swimmer at FLAG Art Foundation is immersive and refreshing enough. Most organizations of its size tend to play things straight, but FLAG is distinct for being unusually committed to the bit. The foundation has proven over the years that it's willing to throw white wall tastefulness out the window by making the absolute, maximalist most of its two floors of gallery space. Its curators have a unique ability to wrangle big name artists in service of genuinely bonkers concepts while bringing together the resources to execute that vision on a grand scale. This can just as easily mean detonating a contemporary-meets-classical pastel supernova as it does maxing out their wallspace with cartoon drawings of people pissing and shitting themselves.

For this year’s summer show, FLAG takes inspiration from an ominous poolside classic. “The Swimmer” by John Cheever is a dark suburban fairytale about a man who attempts to pool-hop his way home from a party, only to slowly and tragically lose his way. It is a parable about downward mobility and the narcotic effects of denial, how missed steps and ignored signs can snowball into the dawning realization that your life has fully gone off the rails. The story is concerned with drunkenness of all kinds — off alcohol, off self-delusion — as a deliriously sunny day gradually devolves into a gin-soaked nightmare. It’s among the most widely taught short stories, yet it has obvious staying power: America high on its own exceptionalism never seems to realize that it’s sleepwalking to its doom.

When the show fires on all cylinders it manages to channel a kind of creepy mid-century gothic that Lana Del Rey would envy. Scenes of boozy summer leisure slosh over into unsettling moments that reek of liquor and death. Robert Gober’s initially unremarkable newspaper print juxtaposes marriage announcements with an item about a little boy who drowned in his pool who eerily shared the artist’s name. The sunniness of Zoe Crosher’s photographs of Southern California beaches is undercut by their grim context: this charming little cove is “Where Natalie Wood Disappeared Off Catalina Island” (2008), this blazing sunset is “Where Norman Maine Disappeared at Laguna Beach From the 1954 Version of A Star Is Born” (2010). She even manages to fit in an eerie shot of Dennis’ last stop before Kokomo for good measure. Leonard Baby is the most faithful to the source material, hauling a bar cart out for his piece “The Pharmacy” (2024) and stocking it with all of the trophies and vices of an outwardly thriving, inwardly spiraling middle class go-getter.

Staring at bodies of water can be beautiful but it can also be a little monotonous, and there are too many artists who are either simply pretty or who hit all the wrong thematic notes. Painting across the board is the show’s weak suit. Dike Blair and Alessandro Raho acquit themselves well by being aggressively tasteful. Ditto Wayne Gonzales and Cynthia Talmadge who offer their own ultra-graphic and pointillist riffs on hanging out poolside. But Katherine Bradford’s sentimental Gumby-looking figuration, Nancy Diamond’s runny watercolor sunsets, Henni Alftan’s Alex Katz knock-off, Ludovic Nkoth’s plunge into the Mediterranean and Stephen Truax’s idyllic cruising scenes are all a little too quaint for a show supposedly concerned with going off the deep end. Amy Park’s watercolor re-working of Ed Ruscha’s Polaroid series “Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass” loses a little bit of its power when shown beside its original source material, although it does bring the show’s latent alcoholism back into perspective — a witty curatorial touch. You can barely make out the submerged body in Calida Rawles’ painting “I Give No Hiding” (2024), which I guess is the point, but the opacity of representation and “spiritual healing” mentioned in the checklist feels weirdly out of step for a show inspired by one of the most self-destructive WASP stories of all time.

The murky psychedelia of Reggie Burrows Hodges’ “Swimming In Compton 628” (2014) fits the theme more gracefully. It’s a swimming pool as a portal, full of bruised color and suffused with a lovely, conflicted nostalgia. It makes for a nice complement with Melanie Schiff’s hypnotic video a gallery over, which captures the abstract neon churn of nightswimming. The absolute stand-out — which is reason enough to visit the show — is by the late Tony Feher. A floor-to-ceiling mosaic of spidery blue painter’s tape, Feher’s piece resembles the cracked underwater view from a submarine at the bottom of the ocean. The effect is beautiful and doom-laden, like a stained glass window offering up the exact opposite of salvation.

Hugh Hayden - "Hughmans" - Lisson

Until recently, there were two shows in Chelsea about the social and political implications of pissing yourself in public. The first was Maurizio Cattelan’s “Sunday” at Gagosian, which featured sheets of 24-karat gold shot-up by assault rifles and a marble sculpture of a homeless man covering his face while urinating continuously for everyone to see. Apart from initially smirking at the idea that Cattelan had “modif[ied]” this art through gunfire, my overwhelming sense was that it was breathtakingly stupid, tasteless and mean. Worse, it wasn’t willing to own up to it! This was selfie bait that sought attention but morally dared you to take a picture, leaving the audience to square the show’s unbelievable wastefulness with the depressingly familiar sight of people struggling to live in the streets. The more pressing and urgent question was: what compelled the artist to make such manipulative slop in the first place?

The second show, which is still up and running, is Hughmans by Hugh Hayden: a maze of bathroom stalls, interspersed with peekaboo sculptures, complete with fully functioning urinals. Hayden has a much lighter touch than Cattelan and clearly seems more inclined to make his audience laugh than to hold them hostage. But despite its outward humor, you get the sense that Hayden has his own mixed motives. The press release is oddly cuddly, an academia-inflected bear hug that seeks to “investigate experiences of revelation, intimacy, desire and sexuality — this time through the lens of the collective experience.” But these claims, which frankly make his show sound like touch therapy or a nudist retreat, rarely bear out in his art. Like Cattelan, Hayden seems to want his art to play in both registers: as some kind of sweeping humanist comment and as a series of aggressively stupid one-liners that dare you to take them seriously.

As an exercise in making the viewer blush and squirm, Hayden’s stalls are actually pretty effective. Watching people waffle over whether to lock the door or sheepishly opening them for the next person to enter is incredibly funny to behold. The two pieces that build on top of this confused etiquette are some of his best. “In the mix” (2024) features a pair of overgrown Timbs covered in wood and lichen that are only visible if you look underneath the stall, cruising-style. “Sleepover” (2023) is a functioning urinal (built for two!) and scrambles the distinctions between public and private while providing the rare opportunity to piss in an art gallery (one I did not miss!).

If there’s a crude pleasure to “Sleepover” it immediately diminishes in pieces like “How the West was won” and “Boogeyman” (both 2024), in which he (groundbreakingly) uses dicks and guns interchangeably as symbols of masculinity and violence. These lame visual puns set the show’s ambition to “transform mundane elements into profound symbols'' all the way back to middle school. There’s nothing wrong with a stupid pun — I’m about to praise another show loaded with them! — but Hayden doesn’t take them in any new or interesting directions. Sculptures like “Elvis” and “Uptown, downtown” (both 2024) are fun for their racial and sexual antagonism (the black skyscraper is erect, the white one is limp) but ultimately shoot blank threats. This wouldn’t be a problem if they were materially interesting. Unlike Cattelan, who uses gold and marble to beat you over the head with their preciousness, Hayden is ultra-considerate. He’s an architect and carpenter by training and is so skilled with his hands that he can afford to be poetic and mischievous in his choices. Which is why when he settles for synthetics it feels oddly sterile. Conversely, “American Gothic” (2024) reminds you how good he can be: a riff on the Grant Wood painting, Hayden chops off the characters’ heads and replaces them with mops and brooms, reducing them (in a horrible modern twist) purely to their capacity for work.

More often, though, Hayden skirts a line between being sentimental and straight-up trolling. “Squirrel” (2024) features a shearling coat papered over in tree bark sourced from Fire Island, playing on the title’s thottier associations to declare in a freaky, covert (and very clever) way that this guy fucks. The “real boy” remixes of “Ebanocchio” and “Nocecchio” (both 2024) are a little too wooden to feel relatable, never mind to stand as “metaphors for the human condition.” I audibly groaned when I opened the door and saw “Plywood” (2024) which features rib cages in different colors of wood—- from white oak to Gabon ebony — hanging from a subway railing. If I wanted cheap multiculturalism, I’d rather it come from AI than a craftsman who must have spent hours and hours working on it. “Hughmans” is a mixed bag and, like a Port Authority bathroom, the most transportive works encounter splashback from its less successful piss takes.

Pat Oleszko - "Pat's Imperfect Present Tense" - David Peter Francis

Pat Oleszko is the kind of gleefully bonkers original that is now vanishingly rare to encounter in New York. The performer and artist, who stands 6’2”, assumes every inch of her grand height by creating work that’s jarringly, fabulously outsized. Her primary subject — like basically every artist’s — is about bodies in space, but Oleszko approaches her art theatrically rather than theoretically. She treats boobs, butts, legs, and vaginas, as props rather than concepts, vehicles for making her audience laugh, stammer, squirm and think. The figure she cuts is striking, and her excursions into the wider world have the same vibe of freaking out the neighborhood as old RuPaul clips or talk show footage of the club kids. She was once arrested for marching with a pope impersonator through the Vatican (title: “The Nincompope”) and she recently hijacked the Staten Island Ferry with a bevy of young performance artists for a climate-themed Pride parade. If she’s been relatively overlooked by the art world, it’s likely because her swaggering, burlesque approach doesn’t fit neatly under the wider umbrellas of “feminist” or “performance art.” She probably has much more in common with consummate freak entertainers like Leigh Bowery or Grace Jones than institutional darlings like Judy Chicago or Marina Abramović.

In her first solo show since 1990, Pat’s Imperfect Present Tense collects decades of Oleszko’s hats, accessories, props and costumes as a small encapsulation of her life’s work. The challenge of any show made up predominantly of costumes is how to bring them to life. This is not a problem for Oleszko. Her pieces are so loony and extreme that a great part of the fun is trying to piece together how anyone could wear them at all. “The Padettes of P.O. Town” (1977) is a three-for-one Boogeyman costume that slouches and slinks like a cunty version of “Pink Elephants On Parade,” while “Tree-Angle” (2010) splits the difference between fashion week all-star and elegantly sinister video game boss. Visual and linguistic puns abound. “The Coat of Arms” (1972) and “The Handmaiden” (1975) are quite literally garments made up of disembodied hands that grope and reach across each mannequin’s body. “Knee-o-Fashism: Wendy Wear-With-All and Her Sole Sister, Ms. Trixie” (1986) is a pair of thigh high boots that double as a miniature drag show. Even if pieces like this, “Tom Saw-Yer” and “Mike Hammer” (both only make sense in the context of a performance, their silliness is so fully realized that you kind of have to tap out. Oleszko is a maximalist weirdo in the tradition of Oskar Schlemmer, Leonor Fini, John Waters, Machine Dazzle and PeeWee Herman; anything and everything can be assimilated into her bizarro universe.

The only pieces that read as slightly dated or stale are the ones that cross over into our recent political landscape. The humor of “A/Bout Dissent” (2014), which recreates a Wrestlemania smackdown between Edward Snowden and Pussy Riot in hat form is a little too timestamped to be funny. It’s likewise difficult to muster much enthusiasm for “Stoke the Vote” (2020), which is admirably flamboyant about the importance of voting, even if it doesn’t do much to diffuse anyone’s apathy with contemporary politics. Some of Oleszko’s strongest work are her inflatables, which ditch the limits of a human anatomy to multiply and super-size body parts into giant pagan totems. “Udder Delight” (1989) is a multi-breasted blow-up deity that’s flanked on both sides by columnar looking ovaries, showcasing the same kind of monumental psychedelic femininity you see in artists like Dorothy Iannone and Niki de Saint Phalle. “Womb With a View” (1990) manages to be even more outsized and crazy: a pathetic little capitalist humping a pair of giant spread legs, which lead to a zip-up vagina engulfing a pitifully small dick. To be truly ridiculous is actually brave and serious business and at her very best Oleszko’s cartoon vision reminds you as much.

Photos courtesy of FLAG Art Foundation, Lisson and David Peter Francis

From Your Site Articles

- The Still Life: NYC's Buzziest Art Openings This Month ›

- Introducing 'The Still Life': An Art Gallery Round-Up ›

- March's Must-See NYC Art Shows - PAPER Magazine ›

- April's Must-See NYC Art Shows - PAPER Magazine ›

- May's Must-See NYC Art Shows - PAPER Magazine ›

- June's Must-See NYC Art Shows - PAPER Magazine ›

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October