The Still Life: NYC's Buzziest Art Openings This Month

BY

Harry Tafoya | Mar 01, 2024

Welcome to The Still Life, PAPER’s monthly roundup of gallery openings in NYC and beyond. Art editor-at-large Harry Tafoya checks in on the buzziest shows to let you know what’s compulsive viewing and what’s not worth the trip on the L.

Photo courtesy of Gladstone Gallery

Conventional wisdom holds that the best way to experience art is to encounter it in a vacuum. And so, most galleries present their artists’ work against blank white walls, making sure to keep their floors as echo-y as possible to spare their viewers from total sensory deprivation. To confront paintings or sculptures in lab sterile conditions doesn’t always do justice to the ideas they represent, especially when the subject matter at hand is gnarly, self-contradicting or just plain overwhelming. “Chaos is a tool and a weapon to confront the world,” Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn once explained, “but not in an attempt to make it more calculated, more disciplined, more educated, more moral, more satisfying, more exclusive, more ordered, more functionable, more stabilized, more simplified or more reduced.” Sometimes the most clarifying approach to art is to make an absolute fucking mess of it.

In keeping with this philosophy, Hirschhorn’s latest show, Fake It, Fake it – till you Fake it, at Gladstone is a DIY disaster zone, an exploded view of online violence stitched together entirely out of cardboard and packing tape. It’s installation as a grating Adderall high, an over-stimulated, beady-eyed assemblage of Red Bull cans, Apple products, and RPG carnage — one that takes in disastrous information and registers it as a funny deadpan joke. Canvassing every inch of a space that’s normally as vacant as the surface of the moon, Hirschhorn has transformed the gallery into a bombed-out, hyper-immersive gaming pit. Desks lined with cracked computer monitors flicker with screen grabs from first-person shooter games as simulated violence spills over into heaps of real-world debris. These piles and aisles form rough alleys for the viewer to navigate, which are interspersed, arcade-style, with life-size cut-outs of gun-toting soldiers and flurries of dangling emojis.

Photo courtesy of Gladstone Gallery

Once the initial sense of visual overload wears off, it’s easy to feel like Hirschhorn is being a little too obvious for his own good. There’s nothing subtle about the Call of Duty assault on the audience’s eyes, and the metaphorical slippage between gaming and warfare happens to be as timely as it is cliche. However, Hirschhorn is too skeptical to settle for a critique as boring as “games=bad,” and this is where the poetry of his messiness comes into greatest effect. The absolute, carnivalesque scale of Fake It also means that it’s irresistible as selfie bait, and the artist seems to anticipate as much. At various points I found myself, phone in hand, zooming in on a swaying emoji, only to immediately feel as though it were laughing back at me. What are the broken screens if not beating your own voyeurism to the punch? The wall to the left side of the entrance is the final thing one’s eyes settle on, and it saves the show’s thesis for last. “Dear World, we are talking about ‘Artificial Intelligence’” it reads, “but why only Intelligence? Why not Artificial Willpower? Artificial Belief?... Never give up human competencies other than intelligence to escape robotic control. Be aware or be next!”

To Hirschhorn, it’s worth interrogating AI not because it’s inherently brain-frying but because so much of our critical faculties and personal agency seems to get left at the door as we’re using, or more often, being subjugated by it. Much like actual images of disaster and war, the whole cartoon sprawl of his show can ultimately be reduced to data and churned out a million times over. In fact, the critic Travis Diehl, recently proved as much by recreating some pretty good visualizations of Fake it. What can’t be replicated however is the feat of imagination and sheer human effort that clearly went into producing these styrofoam pizza slices, cardboard iPhones, knock-off cigarettes and ceramic lines of coke. It’s an undertaking that’s crazy, despairing, stupid, funny, inspiring and, above all else, deeply human.

Photo courtesy of SculptureCenter

Even though they’re easy to spot walking around the city, front businesses exist completely out of mind for most people . The average New Yorker has things to do, places to be, and for one reason or another they are not likely to make regular trips to their nearest “we buy gold” jewelers or DVD sex shops. The familiarity of fronts also gives them an eerie charge; they are both a part of our everyday landscape yet operate firmly underground, their true purpose only clear to those who are already “in the know.” However, just because something resides in the shadows, doesn’t mean that it’s always shady, and to UK-based artist R.I.P. Germain, a front is just as likely to conceal a community enterprise as it is a criminal one. Germain has thought long and hard about the alternative cultures that spring up in the gaps where public policy has failed, honing in on these often ignored “baggy spaces” to understand the coded signals that people outside of the law use to communicate with one another and put signals out into the wider world. For his US solo debut at SculptureCenter, the artist looks deeply at false surfaces, creating facades that both open up and conceal entry into the city’s many overlooked portals.

Placing everyday objects into an art gallery is often a low-effort, high-risk proposal, but in Germain’s case there’s too much obvious creativity and attention to craft to be written off as either half-baked appropriation or a David Hammons tribute act. His approach to the show is layered — literally — and by lifting up the iron grates, his fronts zip open to reveal even deeper and stranger rabbit holes. Most importantly, the interplay that Germain creates between the architecture of these fronts, the graffiti blazed on their surfaces and the funny objects scattered around them, ensures that all of these usually anonymous structures possess a distinct sense of personality.

Photo courtesy of SculptureCenter

Tagged signatures compete for real estate across the show, and the grim reaper that looms over Silent Weapons For Quiet Wars (Hypnotizing Minds) (all works 2024) is a funny shorthand for the artist’s own goth-inflected name among them. Germain frequently piles up symbols until they become obscure, using the build-up of mixed messages as a record that people were once here. Silent Weapons For Quiet Wars (Build & Destroy) is scrawled over in big graphic text, but opens onto a front where curlicues of official-looking store lettering are half-visible beneath blobs of white spray paint, suggesting that it’s gone through several cycles of slipping in and out of legitimate business. Only one graffiti writer, M0DUS L1ST, seems to have been credited in the show, and even if it would’ve meant relinquishing some control, it would have been more interesting if Germain widened his collaborators and invited other artists to stake their turf on his work.

The show’s conflicted high point is Silent Weapons For Quiet Wars (...SEOUL TO SEOUL TO...). Along the top ridge, Germain has had the flags of origin for many British immigrants (Bangladesh, Pakistan, China, Poland, Trinidad and Tobago) carved into the wooden moulding.The spray painted mural that covers its main gate appears hazy at first, but it gradually coheres into a landscape full of fluffy clouds and sloping mountains. When the gate is raised, the paint becomes abstracted while also revealing the Union Jack and St. Andrew’s Cross carved into the bottom panels. What begins as a recognizable sense of place becomes fragmented and distorted the second it’s incorporated with the British flag.

The exhibition only becomes truly legible when approached from every angle. The facade of Silent Weapons For Quiet Wars (RA(C↔G)E) is tagged over in green paint from the front, but emblazoned with a decal that reads “ZAZA” on the opposite side leaving little mystery about what’s actually on sale. Behind each work, Germain has also laid out bouquets of flowers, hot plates, children’s toys, and silver trays with magazines like F.E.D.S. (Finally Every Dimension of the Street) and Cocaine Consumer’s Handbook. It’s a funny, pulpy nod to crime and a play on the idea that behind closed doors people are always cooking up something. To me, the view that reveals Germain’s work best is the one that comes as you walk past the grating, when the built-up layers of half-seen art flit by and you can see the complexity at work but not the whole picture.

Photo courtesy of Christopher Culver and Chapter NY

I started becoming interested in art in the late 2010s, in a period that roughly coincided with the rise of a style of painting no one had a very good name for. Tyler Malone came up with the term “New Queer Intimism,” Alex Greenberger identified it under the umbrella of “Zombie Figuration,” but almost everyone I know refers to this particular wave of LGBTQ art by the far more basic “queer figuration.” Its innovation was conceptual, though it wasn’t really much of a reach: artists depicting gay and trans subjects in private moments, without the burden of politics weighing down upon them. The twist was that this work was almost immediately recast as being implicitly political, pioneering a weepy new frontier of representation that GLAAD miraculously overlooked, but that the global art market certainly didn’t. Even if one swoons at Louis Fratino’s overwhelming romance or Nicole Eisenman’s cartoon friendtopia’s (as I absolutely did), much of this work to me now has the feeling of being trapped at an over-crowded and never-ending Pride parade, leaving little space to do anything but cheer.

The duo of Jimmy Wright and Christopher Culver represent fascinating generational bookends to this trend of contemporary art and their show of drawings at Diana is a small but excellent example of where gay sensibility has been and might still go. When I first heard about this pairing it didn’t initially make sense to me. There’s a 40-year age gap between Wright and Culver, and for the greater part of Wright’s career, he has primarily worked as a painter (his sunflowers are masterpieces of art made in the shadow of AIDS). But what unites both artists is an approach to sexuality that doesn’t shy away from what’s most funny and abject and all-around nasty about the act of hooking up.

Photo courtesy of Christopher Culver and Chapter NY

Wright’s contribution to the show is an aesthetic time capsule, offering work that dates all the way back to the 1970s. His drawings feature the kind of hairy, no-bones (or rather, all bones) promiscuity that you only encounter in vintage pornography, depicting the Golden Age of Cruising in all of its dank glory. Scenes of polymorphous perversity spill out of stalls and into orgies of pulled hair, fucked faces and soiled clothes. Wright’s work depicts these all-out bathroom royales with the kind of craggy, Richter-scale jumping lines and seedy/sensual detailing that one usually associates with Expressionists like Egon Schiele and George Grosz.

Like Weimar Germany, New York’s near-bankruptcy meant that gay cruising could not only thrive but be attractive to men from vastly different class backgrounds and Wright nods to this democratic spirit by mixing hairy hippies, 9-to-5 suits, street queens and platform-shoe’d pimps. These scenes still play out today (I’m told the bathrooms at the Oculus are particularly busy), but as lifestyle choices rather than any kind of unified counterculture. What’s most striking about Wright’s work is the utter brazenness on display, the completely hysterical and unsentimental pursuit of desire. These are genuinely decadent works of art, presenting shamelessness as its own end without qualification, and in their face-melting depravity you can imagine them absolutely triggering Wright’s more romantic contemporaries like Larry Kramer, Andrew Holleran, and David Hockney. Wright’s drawings have a fair amount of brotherly love to them, but very little to do with actual intimacy, although in fairness, it probably isn’t easy to come by on your knees in a subway restroom.

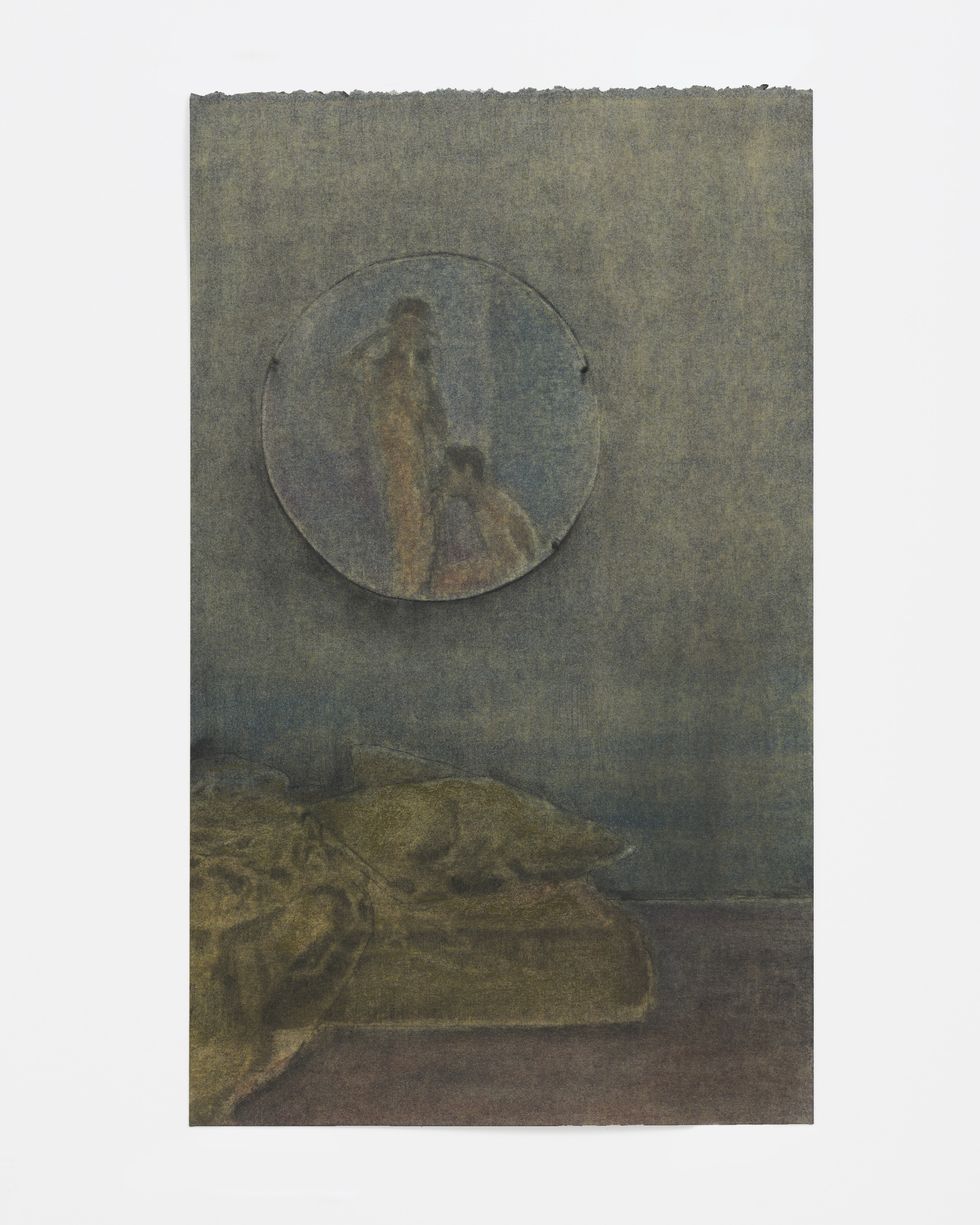

Christopher Culver by contrast works from the remove of almost half a century, from the other side of a historical chasm that spans the AIDS epidemic, gay marriage and the death by gentrification of Wright’s old New York. His layered pastel and charcoal drawings are drab and bleakly beautiful, honing in on scenes of urban alienation and private despair, split between the city’s grimy interstitial zones and domestic scenes where the walls seem to be closing in in real time. Culver is spiritually connected to Wright through the transience of his work, although both men adopt radically different attitudes toward it. Where Wright’s drawings are lit up by a silly, slapstick joy, Culver’s in comparison, are deeply wounded. In pieces like the brutal throat-fucking of “Two Farmers” (2024) sex is depicted as a quick and desperate fix rather than a full body high. His technique gives the piece a gnarly tactility, with the blotchy plains of discolored flesh offset by the chain-link texture of the cocksucker’s necklace.

Unlike the “queer intimacy” crowd, which made a rallying cry out of “friends and lovers,” part of the pathos in Culver’s work is that the subjects are actually his exes; the love on display is dead on arrival, and the ambience between them is of emotional drift. If this all makes his work sound like a bottomless bummer, it really isn’t. What’s refreshing about Culver’s perspective and of fellow-minded artists like Catherine Mulligan, Sam Lipp, Ser Serpas, Kevin Tobin and Shelley Uckotter is that it provides a wholeness to the experience of intimacy, by reminding us that bodies aren’t always beautiful for coming together, and that human connection is richer for knowing it can be lost.