Introducing 'The Still Life': An Art Gallery Round-Up

BY

Harry Tafoya | Feb 07, 2024

Welcome to The Still Life, PAPER’s monthly roundup of gallery openings in NYC and beyond. Art editor-at-large Harry Tafoya checks in on the buzziest shows to let you know what’s compulsive viewing and what’s not worth the trip on the L.

When the average person expresses their distrust for what modern art is and does, it’s not only in response to the true crimes and gross caricatures that the art world is known for. More often it’s to protect something very basic: having faith in their own perceptions without being made to feel like a fool. After all, the only thing more infuriating than having to pretend that the Emperor’s wearing new clothes is to be told that they’re also a comment on capitalism, kink-shaming and the end of the world.

What I value most about art is silence. Not of getting jabbering gallery staff to shut up, but of the quiet that settles in between myself and the work, when I can feel my focus being guided by an artist’s hand toward something larger and more mysterious beyond the bounds of the white cube. Like praying, art works most effectively through heightened and sustained attention, and deep engagement with the very best of its kind can produce a feeling of genuine revelation. Art does not go down as smoothly as a pop song, nor does it always possess the immediate wow factor of a gorgeous/cunty outfit, but its rewards are great because they are so personal. The prize of looking long and hard at a work of art is not just a keener understanding of one’s own senses, but a deeper awareness of where one locates meaning.

I love art, but not unconditionally. The business is unsavory and runs on blood, tears and exploitation, and the discourse that surrounds it can be insular, deluded and drunk off its own self-importance. But at a moment when we’re being plunged deeper into uncanny, algorithmic hell, actively exercising judgment keeps us from being the passive and overwhelmed objects of online distraction and turns us instead into haters and appreciators at greater peace with ourselves and the world. Here is what I saw...

Photo courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

Early in her career, Cindy Sherman took the post-modern lament that “nothing’s original” as permission rather than paralysis, reinventing and photographing herself as everything from clowns to Caravaggio, desperate housewives to real housewives. The approach was funny, novel and infinitely renewable, and it’s to Sherman’s credit that she fought hard to innovate instead of lapsing into a parody of her own style. Since then, the concerns that she and the rest of the Pictures Generation explored — of images subsuming reality, of the whole world reduced to a cliché — has only been sped up into absurdity. Anything that can be imagined has already been aestheticized into a "-core" online — normcore, cottagecore, Barbiecore — a whole universe of algorithmically generated styles with brand new markets springing up overnight like mushrooms to service them. At key moments, Sherman has navigated her way out of dead ends by embracing new technology, and at this critical juncture where apps and filters are available to LARP as any lifestyle it wants, Sherman has once again leaned hard into her digital tools. Her latest show at Hauser & Wirth is a late career highlight where she’s given up the game of observing and mimicking others in favor of making her own freaky, inspired mess.

Sherman’s show is not her first foray into using digital art techniques, but it is by far her best. Early experiments posted to her Instagram have ranged from twee to terrifying, combining the diaristic quality of a friend’s mom’s selfies with face-melting, cursed image weirdness. This time around, the artist has raised her game, taking portraits and suturing them into grimacing, grayscale mutants. Superficially, Sherman’s work resembles chopped-and-screwed modernist collage, where everyone from Picasso to Man Ray had a field day perverting the female form. But rather than “investigating” or “problematizing” an existing art tradition, Sherman’s work feels much closer in spirit to John Waters, Amy Sedaris and the more mutilated end of drag: reshaping and negating her own image in a profoundly unserious way.

Photo courtesy of Hauser & Wirth

The seams between Sherman’s stitched-up faces vary from subtle to striking, but they ultimately cohere in their alarming glamor. Photos like “Untitled #654” (2023) possess the exaggerated, botched features that make figures like Jen Shah or Jocelyn Wildenstein so iconic, while others like the toucan-beaked “Untitled #634” (2010/2023) or the cavernous nostrils of “Untitled #639” (2010/2023) are realistic enough to imagine jumping out at you from the shadows of a prestige horror movie. But once the initial shock of their appearance wears off, these garish pictures become mesmerizing for their fine detailing. Everything is considered, from the torched eyebrows and overdrawn lips of “Untitled 649” to “Untitled 629,” where Sherman’s bulging Buscemi eyes are so prominent that it takes a second to realize she’s actually hand-painted her teeth pearly white.

Across vastly different styles and looks, the common denominator for all of Sherman’s work has been the pleasure she’s taken in remixing her own image. That, after all of these years, the artist still able to catch herself in the mirror and think her mug isn’t nearly as fucked up as it could be, is enough to make you smile like this.

For more info, visit hauserwirth.com.

Photo courtesy of Theta, New York

German painting can be colorful, chaotic and cartoonish, but it is almost never casual. Even at its most brazenly silly, the modern tradition always has a distinctly serious edge, giving the impression that something far more lofty and conceptual is taking place than the silly puppies, blurry porn or penis sharks might immediately suggest. Gritli Faulhaber manages the unusual trick of being able to tap into this high-brow lineage, while remaining resolutely breezy and low-key. The Zurich-based artist specializes in painting as a form of collage, mixing and matching a grab bag of found imagery until they form a cohesive whole. Her latest exhibition, The Living at Theta Gallery, feels like a glamorously messy but oddly unified closet, one that manages to contain a wide range of styles — from Impressionism to Art Nouveau, to Pattern and Decoration and Pinterest — while still retaining a signature that’s distinctly her own.

Unlike other artists who’ve made moodboards into their primary medium (see Al Freeman, Tom Koehler), Faulhaber’s work thrives on interesting comparison rather than shit-posting contrast. The best example is the dialogue that plays out between the show’s two largest paintings. With its build-up of gorgeously hazy primary colors, “Ohne Titel (Palette Revisitée)” (2021) could easily be confused for a major abstract expressionist piece, but so too could the painting of a flung sweater that sits opposite from it. Despite its humble subject matter, the clever interplay of blankness and color in “Hobby Couture (Billabong)” (2023) elevates a tossed-off garment into an understated color field painting.

Photo courtesy of Theta, New York

More than other artists, Faulhaber lives and dies by her eye as a curator as much as her painterly hand and a handful of aesthetic tricks go a long way to establishing the show’s funky sense of unity. Blocky compositions with large expanses of white canvas, the recurrent use of creamy beige and expensive-looking wedgewood blue and a taste for flowy feminine figuration. At various points, Faulhaber replicates and riffs on paintings by Berthe Morisot and Gerda Wegener, who she incorporates to highlight the mistiness and exaggerated lines of her own work rather than carelessly name-checking for its own sake.

The wide range of genre is impressive, and even then the occasional clunkers like the all-black pigment painting “Debutante” (2023) or the wince-inducing text piece “Abstraction/Figuration” (2023) register as being oddly cohesive instead of eyesore offensive, the way a Prada dress might share space on a rack next to a stupid meme tee. Artists and gallery staff often complain that it’s unfair to criticize them for the press releases that accompany their shows, but in Faulhaber’s case the text does her a particular disservice. To put it simply, the essay’s dense artspeak makes the work seem far more high-minded and heavy-handed than it actually is. If you go visit the show, ignore the gallery text; in its easy eclecticism, Faulhaber’s work speaks beautifully for itself.

For more info, visit theta.nyc.

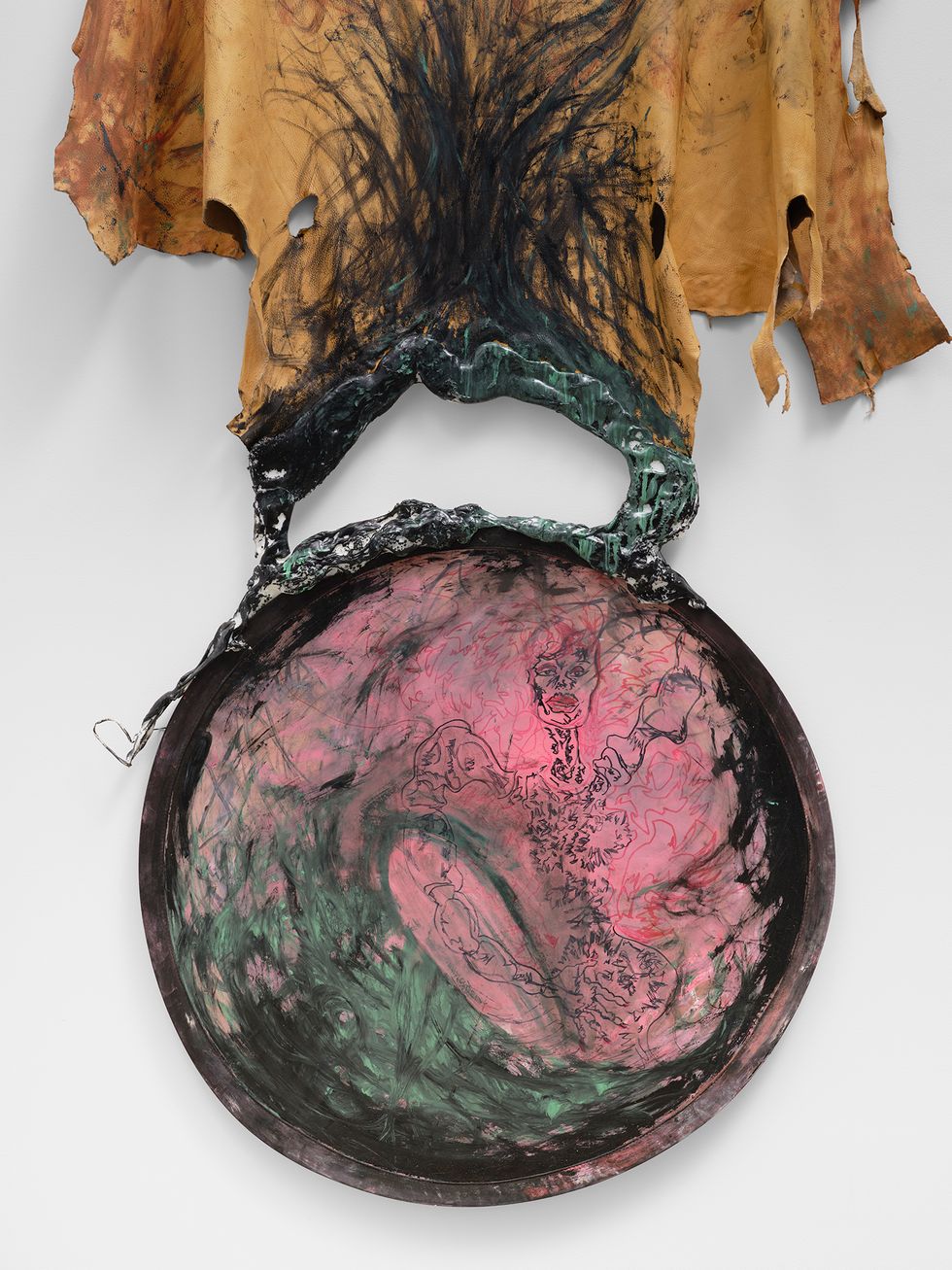

Photo courtesy of Petzel Gallery

Raphaela Vogel’s art fits into the German tradition of silly-seriousness, but also of the gesamtkunstwerk — the total work of art. Unlike Gritli Faulhaber’s painting, there is virtually nothing laid-back about the surreal videos, mangled sculptures and gigantic installations that Vogel creates, which aspire in their sheer size to completely overwhelm her viewers. After making a splash at the 2022 Venice Biennale with a train of misshapen giraffes pulling a model of an oversized, canker-ridden penis (“it takes a lot to get it up...”), Vogel recently made her US solo debut, In the Expanded Penalty Box... at Petzel. The result is a kind of nightmare techno-opera — part hyperbaric selfie-chamber, part Cronenberg body horror — all staged in service of what feels like a single obscure half-joke. Depending on your orientation, Vogel’s commitment to showmanship is either completely audacious and inspiring or indulgent and alienating. True to the spirit of maximalism, I kind of felt both!

Photo courtesy of Petzel Gallery

The variables at hand in Penalty Box are fittingly diverse and crazy. Beneath a terrifying cyber-pyramid, in which a video of Vogel prancing around in a multi-faced Nosferatu mask is projected, several molten humanoids beckon the viewer to a wall of cameras primed to take a barrage of photos of whatever brave soul that wanders in. After a few seconds of death metal shrieking, the pictures are then played in a slideshow on the opposite wall to a German ditty from the 1930s called “Jede frau ist schön” (Every woman is beautiful). This entire scene in turn is flanked by gnarly, painted animal hides and repeats itself every few minutes.

The fun of the show lies in trying to interpret the Easter eggs that Vogel has scattered throughout. Make of them what you will: a comment on digital personhood, the pain and ecstasy of being perceived, the logical endpoint of being a terminal theater kid — all are valid explanations, all are equally plausible. The selfie wall, the haunted tech, the ominous soundtrack are all jagged puzzle pieces that don’t add up to a bigger picture, and it’s to Vogel’s credit that she’s generous enough to leave them unresolved. If she had saddled these fragments with backstory or political significance, it truly would have been indulgent and unforgivable. If I personally struggled to get lost in her work, I still very much appreciate Vogel’s commitment to her vision. The show is a fully realized, internally coherent system that invites viewers in with its awesome scale and leaves them on the other side wondering what the fuck they just saw.

For more info, visit petzel.com.