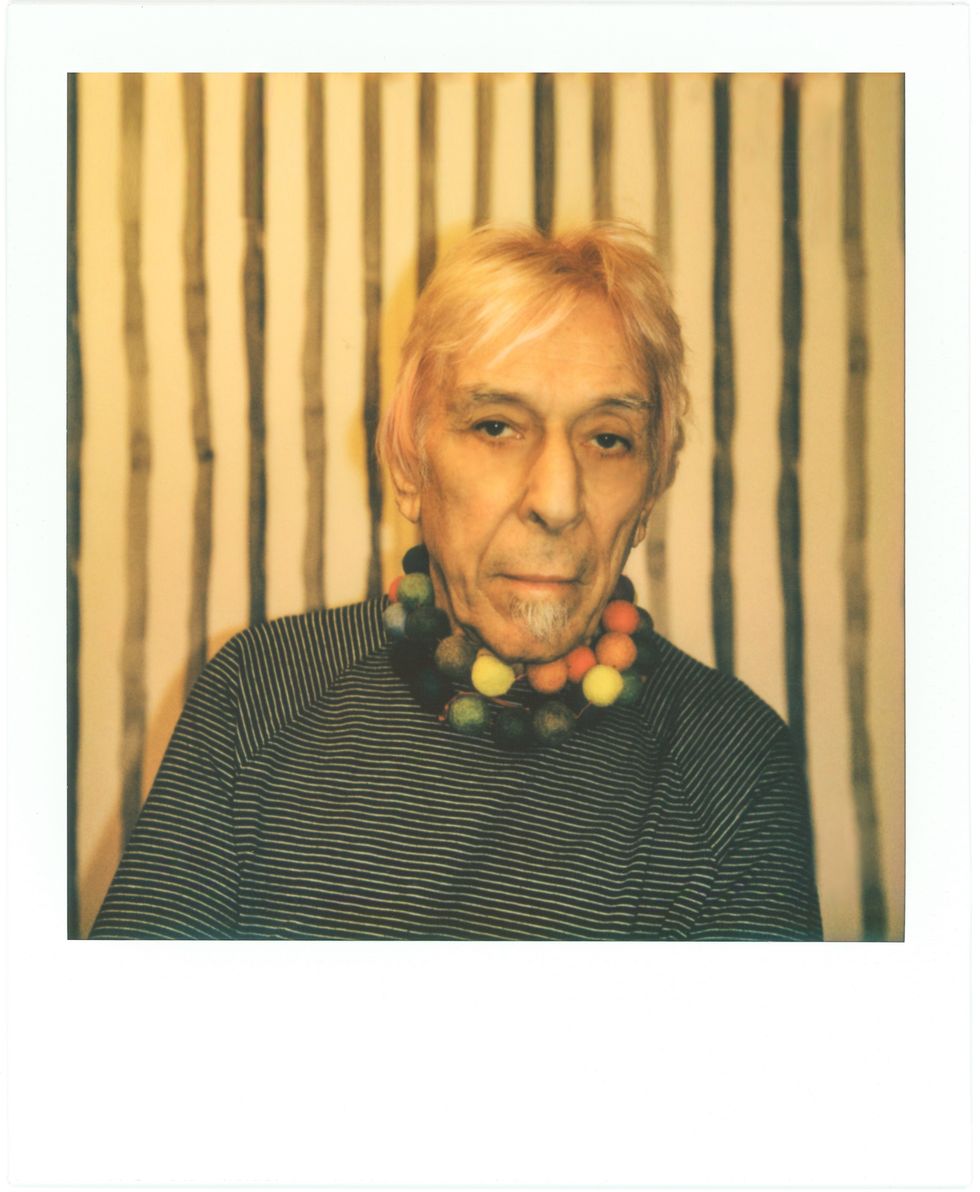

John Cale Never Rests on His Laurels

By Tobias Hess

Jun 18, 2024The thing about this business is sometimes you get an email asking if you’d like to speak to John Cale.

The answer is, of course, “Yes, I would like to speak to John Cale, the legendary artist, producer, and composer.” But if you’re me, you’re likely to be unprepared for the existential scurry to follow. Because where exactly are we to begin?

We could start in rural Wales when he picked up the viola and found himself entranced by the possibilities it unlocked. Or when he was pulled by the Bohemian winds across the Atlantic to the furnace of the ‘60s downtown avant-garde. There, he acquainted himself with John Cage, who introduced him to La Monte Young, the Fluxus composer whose contemplation of drones and harmonics became embedded in Cale’s next project, The Velvet Underground.

Yes, we could start there: at the album that changed the trajectory of popular music, when Cale and Lou Reed clashed in a glorious flurry to produce a body of work that was at once visceral and strange, poetic, yet unencumbered, with forever classics like “Sunday Morning,” “Femme Fatal,” and “I’ll Be Your Mirror.”

We could start at its iconic place in pop culture, cemented by its simple cover, a mere banana designed by Andy Warhol, who managed the band during a productive, ultimately messy affair that would rocket each of the Velvets’ members towards pop-culture shaping careers.

Or, we’d be well within our right to start right after. Though his time with The Velvet Underground ended abruptly, Cale never paused or “rested on his laurels,” a phrase he repeated throughout our conversation, invoking it like a grave sin. He continued to shape the sounds of popular music by splitting the difference between rock and the avant-garde, producing Patti Smith’s Horses, The Stooges’s self-titled debut and Nico’s perplexing, enchanting solo outing The Marble Index, among many others.

That’s to say nothing of his solo career which has careened between the novel and delectable, from the quaint Paris 1919 to the forever danceable Wrong Way Up with Brian Eno, to last year’s Mercy, which found the 82-year-old stalwart collaborating with contemporary favorites like Weyes Blood, Laurel Halo, Animal Collective and Tei Shei. Mercy, which was made during a time of deep productivity in the midst of the pandemic, was a welcome gift to Cale’s longtime fans, who hadn’t heard a new album from him since 2012’s Shift Adventures in Nookie Wood. But Mercy was just a taste of what was to come.

During that same period of creation, Cale also made POPtical Illusion, a collection of 13 songs that vibrate with a sense of wandering memory. On album-opener “God Make Me Do It (don’t ask me again),” Cale’s low warbling voice calls out, “There’s someone whispering in my ear tonight,” evoking those many colleagues, comrades and loved ones whose presence has shaped his output throughout the decades. Though a heaviness lurks, there’s also smirking humor here, both in its sonics — which hop between cinematic soundscapes, vast synth oceans, peppy pianos and trap drums.

From the beginning to this ever-productive now, I was struck by his complete and utter matt-of-factness as I paced Cale's career with him. He is an artist with ambitious aims and ideas, but more so, he struck me as a practitioner. Maybe owing to a working-class, Welsh Protestant background, the simple act of work, of doing the thing and remaining humble and diligent, seems to be the thread that binds his legendary lifetime.

“I am working towards the same ends as when I started when I was 14 in Wales,” Cale tells me at the end of our interview. As someone who’s listened to Cale’s work myself since I was a young boy, I am thankful for his continued diligence.

This is your second album in quite a short period of time, after a long break from releasing before. What was your creative life like before the pandemic? And what was it about that moment that kind of sparked all of this momentum?

Well, it definitely was derived from the pandemic. That sort of shut all the doors. I don't know why it happened other than that. It became a period of intense work. I was very intensely involved in writing and I was really happy with it. I got a lot done. It's still going on, so I'm not shy about getting on with it. You know, when those things happen, you just scramble as fast as you can to take care of what you need to do. And you try not to lose sight of what your goals are with the music.

Certainly. I just wanted to go back for a moment. You came from Wales and quite quickly found yourself in the center of the New York avant-garde. It's quite the leap. What do you think prepared you dispositionally to go headfirst into the New York avant-garde coming from a more provincial background?

Well, it didn't take very long. From the time that I got the viola from the school orchestra, I moved along into different kinds of composition. It was a rough and tumble kind of period of moving from different styles of music. Once I'd gotten into grammar school and then on to Goldsmiths College, it was all very exciting.

I know that working with La Monte Young was a very influential period in your early career. I'm curious what about him and that music specifically resonated so deeply with you?

It began in London, where I got to know Cornelius Cardew there. I was aware of what [German composer Karlheinz] Stockhausen was doing, and it was very entertaining to hear what La Monte was doing in regards to Stockhausen because he was at odds with him. It was a period where there was a changing attitude towards tonality in Europe. He was really driving a different kind of perspective than Stockhausen. Stockhausen was hellbent on saying, “You've got to invest in new music.” In Europe, it was: you just make sure that you have a 12-tone scale, and if you don't have a 12-tone scale, you can have a 12-tone instrumentation. It was a quick shift that was going on in Europe. La Monte was from the West Coast jazz groups, it was Terry Riley, Terry Jennings, etc. So when I got to New York, La Monte had already established himself. And John Cage was very generous with his recognition [in connecting us both].

I know La Monte’s music was infused with a sense of mysticism and spiritual ideals. Did you take to any of those ideas having come from a Presbyterian Welsh background?

That makes me laugh a bit. Anything Presbyterian and related to radical music was a strange world to inhabit in the ‘60s. But once you got into New York, that was what was there. The thing about the scene in New York was that with whatever La Monte was doing, he was also joined by other artists, painters, sculptors. I was really fascinated by the intellectual side of La Monte’s theories, because they covered a lot of ground. They weren't really so much about music, but they were. He'd write pieces that were instructions for performers. He would have one instruction be “draw a straight line and follow it.” If you know his stuff, then you know there were two or three really important pieces like that.

I'm curious then about the transition towards music with lyrics and rock music, especially if you're in this rarefied avant-garde space beyond words. How were you approaching that?

Well, the lyrics were there. I was really into improvisation. And a lot of the times that Lou and I sat down and threw some ideas around, it was really something that was not confined to just lyrics. It was part of the creative process with lyrics and music. So you start with music, or you start with lyrics, but what was important was that you got on with new things that came along. Lou was remarkable like that because he could, at the drop of the hat, just turn around and write lyrics about what happened that morning at breakfast. That spontaneity was very important.

So you didn't see as much a distinction between the world of rock music and the world of ideas expressed in this downtown avant-garde composition scene?

I think it was all joined at the hip. You really got a lot out of the society that was in New York at the time: the musicians and the sculptors. It was a very exciting time.

The new album is called POPtical illusion, which evokes pop art and Warhol’s notion of mass culture. As someone heavily involved with Warhol’s factory, what did you take from his ideas?

I think what was memorable about it was the gentility of it all. It wasn't all furious creativity. It was very gentle and very progressive. Whatever was going on in Germany was very different from what was going on in New York. I learned a lot from that, from the way that the styles changed between what was happening in New York or what was happening in LA and so on. We tried to blend as much of these ideas as possible.

Your career, more than anyone else’s, has tied the ideas of the avant-garde with commercial rock music. Many people would see those worlds as distinct and often at odds, but I don't get the sense that you ever did.

No, you're right. I didn't see any of that as being contrary to everything else that was going on. If you wanted to get work done, [the factory] was a furnace to really live in for a while. And, there was no limit as to what you would start or end with. It was such a hard-working milieu that everybody was getting on with it. Andy and his gang, the Factory, were very productive. But it was not a ferocious existence. It was kind of fun and gentle.

I'm struck by the diversity of types of collaboration you’ve had, be they different musical artists or with different mediums. Do you have criteria for what you look for in collaborators? Is there some kind of universal quality that attracts you to creative partners?

I think my rulebook is about how much I can get done. I never sit still. I get on with it as much as I possibly can. All the people that I've been very fortunate to hang out with are very interesting musicians and sculptors and so on. It wasn’t meant to end. It still isn’t.

MERCY, your last record, featured such an exciting array of musicians that are so important today. Tell me a little bit about how you picked those collaborators?

I tried to combine as many different things as possible. The collaborations were sometimes a little fantastic, sometimes stylish and emotional. I just went with whatever was available, and I really enjoyed it.

Your last record was defined by that community of collaborators and this record was made by your creative partner, Nita Scott. How did you decide to embark on this one?

It was just looking at what the circumstances at the time were about and working it, pushing the edges again. I had a good time doing it. I wrote a lot of songs in that period and I was very happy about how it all proceeded. It was a hard road to charge down. I didn't want to stop with one idea. I was really happy with how careful I was about not doing the same thing twice. That's always important to me. Every day I would be in a studio doing a new song. Every time I got to the end of an idea, I would just go back to the drawing board and start again, and then have as many new ideas as I possibly could.

I know that hip-hop inspired you and factored into the production of this record. Do you remember when you first encountered hip-hop and what about it inspired you?

Yes it was, J Dilla. And later Earl Sweatshirt and Vince Staples. Finding out about these people and trying to understand what their appreciation of what they were doing was was very productive. I enjoyed listening to all those new rambunctious artists.

The musical process changed so much over the years with the advent of computers and software. When did you start working with computers and has that shaped your music?

Well, it started a long time ago. When you create, you run into the usual limitations. You've got a lot of ideas that you want to try, but you can't really follow through on it every time. It's not something that you call somebody up and say, “Hey, how'd you do this?” One way or another, I found a way to get through the density. The density is really half the battle.

One of the things about the avant-garde is that you really don't want to use other people's ideas. The period with La Monte, for instance, was two, three years and there was no such thing as “remedial” in that period. It was every day with Tony Conrad, with Marian [Zazeela] and La Monte. That was a lot of energy that went into that. It got to be really exciting.

Everything you're saying seems imbued with this kind of unstoppable work ethic and an insistence that you won't rest on your laurels.

I'm not trying to tell everybody that they should be doing the same. But I just found it to be really elevating.

It seems like you have a sort of enduring faith that music will maintain. Is that right?

Absolutely. There was nothing that really came my way that made me want to stop, or suggested that I should find another job. There were a lot of really creative people in the world, and I was impressed by it.

The circumstances in which I'm creating this stuff are something that keeps me going. I'm working towards the same end as when I started when I was 14 in Wales. It's my instinct that makes me push in that direction. It could be much more complicated, I know, but I don't really want to do that. I want to create as much variety as I can.

Photography: Madeline McManus

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October