Talking with Charles Jeffrey about his work is not unlike those long, winding conversations you get lost in with some stranger at the after-afterparty. A few drinks in mixed with extreme sleep depravation, sentences become stories and you find yourself connecting the dots about life with no inhibition. It's all a bit scattered, but inspiring nonetheless, like you've discovered the truth in a sea of hazy, haphazard 4 a.m. thoughts.

Jeffrey, the London-bred fashion designer whose work has become synonymous with queer nightlife, operates a bit like this, thrusting all his ideas out into the world and encouraging his audience to draw their own conclusions. He thinks and speaks with no restrictions, and the result is somehow still poetic and poised, which has earned him comparisons to former fashion bad boys Alexander McQueen and John Galliano.

In his second installation for Dover Street Market New York, Jeffrey leans into this limitless approach to create HEX, a multidisciplinary in-store experience influenced by pagan symbols and rituals. Amidst the 27-year-old designer's unruly, colorful scribbles stands a giant sculpture, called the LOVERBOY yeti, which he constructed for visitors to rub like a Buddha. He says it offers "health, wealth and prosperity" to shoppers who touch his face.

PAPER sat down with Jeffrey to discuss the making of HEX, and how he's maintaining an outsider edge while catering to the luxury market with his rising brand.

Charles Jeffrey January 2018 (Photo via Getty)

I was just talking to my friend, whose brand Private Policy is deeply rooted in New York streetwear, about the difference between New York and London identity. I'm curious to know what you think coming into NYC, and your perspective on New York fashion.

I've had a little taste of it more from a nightlife angle from when I first got introduced to New York. The first time I went was about 2 years ago. So I had that sort of romanticized idea from Downtown 81, Andy Warhol and late '70s. That's my favorite era, and then obviously as a voyeur of New York from Britain there's the whole Hood By Air movement — Vaquera, Eckhaus Latta, and all those people. Then when I went, I got a taste of it from a nightlife angle, and the idea of dressing up being a way of expressing yourself, which we shared in London as a way to engage in fashion design. I think it's interesting to see how we're perceived in New York City, as well.

Related | Private Policy Invites You to Give a Speech During NYFW

How do you think you're perceived by NYC?

There's a few mentions from press with references to previous designers like [Alexander] McQueen and [John] Galliano, saying that I'm a new version of that. I guess I feel like that sort of young Brit designer. It's a big narrative to follow, but I think that's how we've been perceived. With these projects we're doing more [in the U.S.] I think it would be interesting to see how that's bounced off because there's a lot more avenues I would like to be known for.

It is interesting, people latch onto these certain things with you, like nightlife and other radical queer designers like McQueen. None of these references are negative, but it can be limiting. How do you want to be perceived?

It's definitely a title I'm quite comfortable with in some ways because it's valid and authentic, like we know our brand did come from the club space. The way we try to produce our shows has the same energy as some of those previous designers. How I see my shows happening now is that it's a body of work for me as an artist, so I always like to see the show as a form of happening, which is a phrase that comes from old New York and Claes Oldenburg. In that time and era, they would make a space, and create the artwork in that space, and people were performing the work in that space; that was the proposal of it. So I see a few links to that in the workplace. I would like to push the button a bit more and in some ways doing this [Dover Street Market] installation is a good place to do that. At a certain point it is important to concentrate on doing the work and just letting people perceive it how they want to. I think it's a gift in a way to get that feedback, especially from the people that we've heard so far.

Related | To The Moon and Back With Sussi

What were your intentions with this DSM installation?

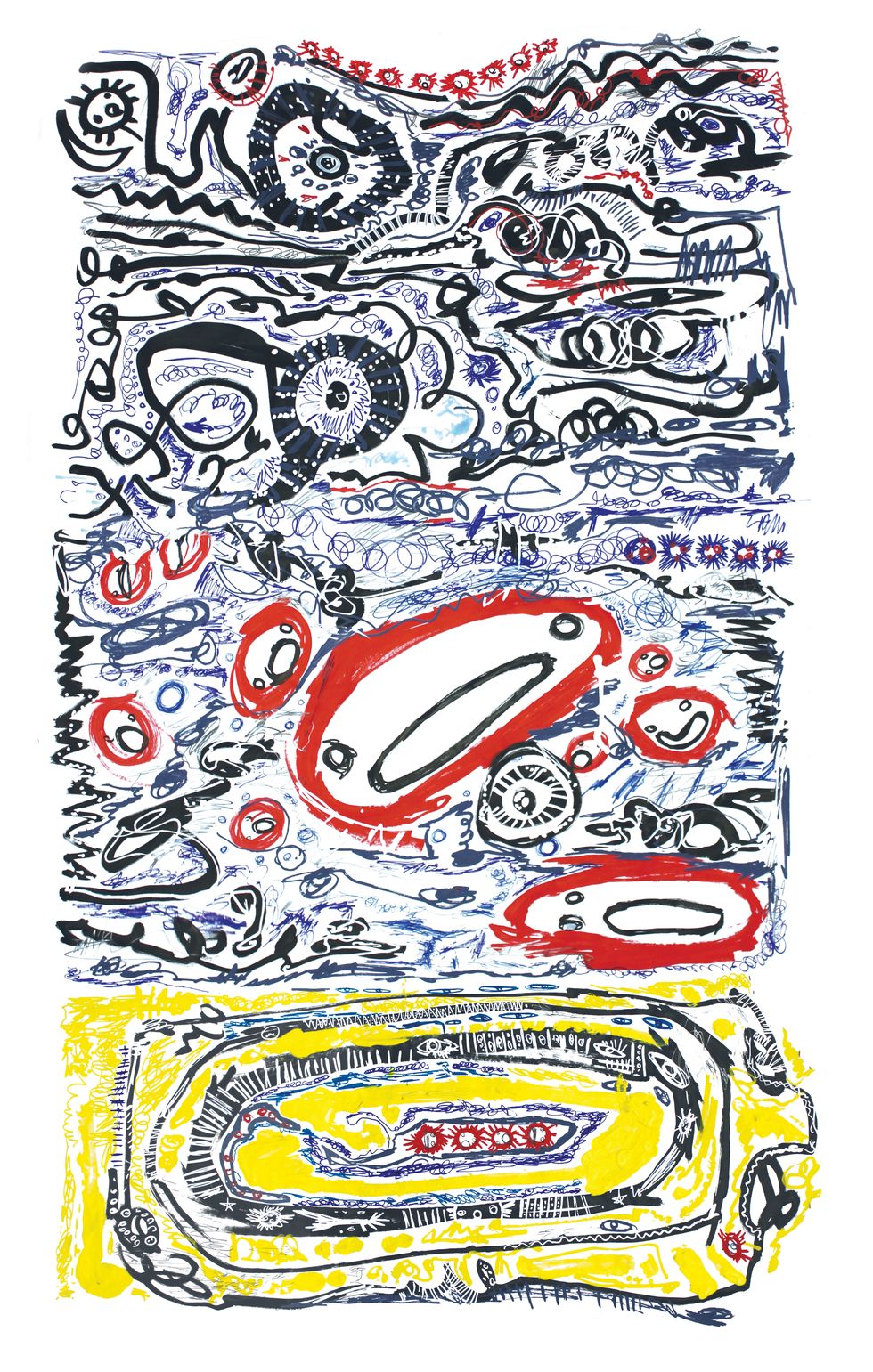

It's the second time I've done an installation in the New York store. The first time we did it, It was more of like a big tapestry, and we just kind of stapled it to the wall and then that was it. This one is sort of an offshoot of the primal work I've been doing in my drawing and illustrations. It's sort of the work I did with the Now Gallery in Greenwich; I did an exhibition called The Come Up, which was a series of sculptures littered with illustrations, and then we did a performance in that space as well on the opening night. This was an offshoot of that and based on a lot of Celtic symbols and signs mainly from the Picts clan in the east of Scotland. They were known as paint people and used to adorn themselves in symbols and signs. My illustrations are scrolls and marks, and the interplay between all those marks together.

This one [in DSM] is a LOVERBOY yeti, which is clad in all these scribbles and marks. We're almost christening it with the people who rub its face to get good luck. I always loved that idea of giving something a sort of magical feeling. I think there's something weirdly existential about it because you're choosing to give it that property and you make yourself feel like you're giving yourself good luck if you rub it. I have one in my room and I always rub its belly every morning if I can [laughs]. The space is incredibly colorful and busy and the decorations are sized to be full fantasy. It's many different mediums — it's not just on the wall. it's going to be on the rail, on boxes, on sculptures.

Illustration Courtesy of Charles Jeffrey

You mentioned the word "primal." What about that interested you as a starting point for this installation?

I think when I was studying, I always tried to work in a very formulaic way because I thought that was the way you were supposed to work. It just never really worked out for me, and then I think the most successful work that I've done always comes from this very primal endeavor, where I really trust my gut a lot more. I think any sort of decision and any sort of designing comes from a very primal place. I always think it's the most effective because it doesn't feel formulaic, or overthought. It feels very pure, and there's this amazing interpretation of creativity that came from the era where gods lived in the walls. If you're a creative person, it was like something flowed to you and then it was an output of that. I think that's a really healthy way to look at it, as well. Instead of something that's dealing with my own ego and emotions, my most interesting work comes from not thinking too much — when it just is what it is.

"Instead of something that's dealing with my own ego and emotions, my most interesting work comes from not thinking too much."

I feel like everyone is so obsessed with logic and reason, right now. Do you feel what you're doing is a response to that?

I think in some ways it's this kind of response to the frustration of trying to be logical. Especially at the moment, I'm trying to be a bit more puritanical and taking in as much information as I can. I've been watching videos on quantum physics; I've always been really interested in space and science, in general, but there is this really amazing YouTube channel called "In a Nutshell" that's done well. I find it all incredibly interesting and then I think to take it and put it into place with something else. So for my new collection we're going to be doing in June, I'm interested in concepts that I learned in cultural studies, and then incorporating that with primal imagery. I'm working with this knitwear artist, and now it's sort of reminded me of this logical way of thinking — the idea of the grotesque and the body. Because it does live together, it's just for peoples interpretation to make that happen and I think that's not necessarily my role as an artist to do that.

It does sound very complicated, even hearing you connect all these thoughts and ideas out loud.

There is a big output of lots of things, and I do that to surround myself with people who can help connect the dots in some way. I think it will always make sense for me in a visual sense.

How do you go about dabbling in the luxury fashion world and still staying connected to the marginalized communities you've always valued?

There is an element of putting it effort. My day-to-day is very much based on being in the studio, looking at my team and doing the work that is required. I do gain a lot from putting the effort into going to different exhibitions and performances and cabarets. It's definitely much more of a effort now because a lot of people have grown up and moved to different places or are doing different things than we originally were connected with. For example, I went to an art show called Cream Concealer at the Flying Dutchman London, and there were about 10 people. It was really interesting to see an artist who's only like 4 or 5 years younger than I am — to see their viewpoint in the world. For me that was really inspiring to know there can still be some pockets of things going on. By putting the effort in, you can gain a lot.

Related | Will Diet Prada Save Fashion From Itself?

When it comes to making clothes, what is the process of maintaining that outsider point of view? At the end of the day, Dover Street Market is a luxury department store — an incredibly cool one, but still luxury.

There's always a process that's a mixture between chaos and control. So I think with my type of medium, it's a primal way of making proposals or clothing or artwork, but there's always that element of refinement coming in logistically. So with Dover Street Market, I could have just given them a print out of an illustration I had done at the studio, and sent over something pre-done, but the whole idea is that there are some cleanly laid out elements but I definitely have to have my own hand on it. With this sculpture, I sent it over to get fabricated but the finishing touches are done by me. All these processes have to happen in order for LOVERBOY to be there. We do all little projects and I always think about commercializing — how price points are going to be if we're going to have to schlep on shredding. Is this going to be too expensive? There's all these conversations that are happening and you have to be creative to in order to come up with solutions. I think it's a really fun job actually to problem solve.

One of the biggest challenges for new designers is reinforcing your point of view until you gain the industry's trust. Do you think you've managed to do that?

It's still a young business, so I think it's going to be a struggle for a good couple of years before we can find ourselves in a place where we can be self-sufficient. But definitely the angst of not knowing if I can pay my rent or not has dissipated a little, which is nice. We're doing bigger projects that are giving us more cash flow. I think people are expecting us now to survive as a business, and I think people are actually attracted to that in a young designer once they know you're doing well. If you continue to do these very creative outbursts of energy but they're not really making any sales, people's perception of you changes. People are more aware of what we face as young designers — it's different from the McQueen and Galliano era, where they were actually paving the way for people like us to exist. Critics would be more interested in the stories these designers were telling, whereas with us our generation they're definitely looking at how many stockers we have, or what's our market like in Asia, or what is our customer age in New York. I really enjoy that type of stuff and find myself unconsciously knowing a lot of this information. It's like reading the news now.

"It's about everyone's identity being valid wherever you come from."

As you grow this business, how important is it for you to be hands on, because realistically you might not be able to do that someday?

I think part of what our DNA stands for is this very DIY hands-on, primal vibe. But I do want it to become a self-sufficient business and want to be able to expand it to a place where it doesn't always have to be me and my scribbles even though it probably will be like that. My vision is always to have the brand be the place where we're open to collaborate with people and still be refined. So I would love it to continue to be that way — it's that sort of dynamic that brings in different creative voices underneath this overarching vision for myself, and then I obviously have my own practices as an artist. Our product comes from that too, and I just don't think that will ever go away — that hands on process. As we get bigger and bigger, it's just about having that mission statement or manifesto that we can always go back to so we don't fluster what we originally stand for. I think it's about time we get a manifesto actually, tattooed [laughs].

What would be that manifesto?

I'm not the best with words, but it would be about the fact that we're doing something for a reason and that reason being ultimately trying to achieve the most creative output possible and building an environment for that to happen. It's an environment so other people can be apart of that, as well. It's not just a singular vision, it's a melting pot of ideas, which it always has been whether it was on the dance floor or being in the studio. Andy Warhol's Factory was just a big warehouse where he was just doing his work and people were doing heroine. The romantic offshoot is that I would love to build some sort of space that is an environment that can allow for lots of things to happen. It's inclusive, because we do operate our brand with a queer spectrum. That's what we came from and it's very important for us to reiterate that, but I think the artistic outputs don't necessarily have to be queer things. It's about everyone's identity being valid wherever you come from. We're about support and I think what we're trying to do with the brand is explore these ideas, but have different outputs you wouldn't necessarily expect. We always tend to go back to that when we're problem solving — it's always about going back to that PH level.

Charles Jeffrey's HEX installation is on view at Dover Street Market New York through May 23rd.