Statuesque and fair, 28-year-old Zyra West waits for me in the courtyard outside a gray-shingled townhouse, smoking a cigarette. Her pink tooth gems catch the glint from the blood-red sun sinking behind Wyckoff Ave. She’s wearing a vintage Hustler graphic tee and spandex shorts and ushers me inside her home.

Stepping into West’s pink, sun-drenched apartment feels like you’re entering a Bushwick Barbie Dreamhouse: Barbie’s edgy Big Apple pied-à-terre. “Brooklyn is Tattoo Mecca for self-taught artists,” West says, chattering as I peel off my boots. The private tattoo studio scene, crawling with talent and nourished by queer kinship, is roaring in Brooklyn and is indicative of a culture shift in New York’s tattoo landscape. Spaces created by and curated for the queer community challenge the traditional tattoo parlor environment by creating alternatives for tattoo lovers that don’t feel the heavy-metal-blaring, leather-and-stud, pay-per-hour tattoo shops exist for them.

West converted her living room into a tattoo-slash-painter’s-studio. “It’s just the two of us. We have music playing, maybe burn some palo santo,” she says, describing the “professional but intimate” vibe of her apartment-turned-private-parlor. “It ends up being really intimate and relaxing.” An aisle is tucked into a corner with shelves of craft supplies: textured papers, crinkled paint tubes and bowls of metal instruments. Nailed to the blushing pink walls are her original works on canvas: dramatic oil paintings protruding with chunky, layered acrylic, busily animated with provocative text and nude women spilling breasts and dripping with sexuality. Cut-outs of flash tattoo pieces she’s done are collaged and taped around the hung works.

Across Myrtle Avenue, in the cavernous basement of a Bushwick brownstone, best-friend-and-roommate duo Coco and Indigo play tropical techno and playfully bicker over who has control over the aux. Indigo prefers “chill music,” but Coco insists that slow beats cause sluggish hands. “I’ll end up tattooing slower,” Coco says, laughing.

They scouted their apartment on Craigslist, a labyrinthine four-bedroom with an attached basement space decorated with “eco-futuristic” furnishings. “COVID essentially brought New York back to when it was still legal here 20 years ago,” Coco explains. “In the ’80s and ’90s a lot of tattooers were tattooing out of their homes, and so now we’ve shifted back to that.”

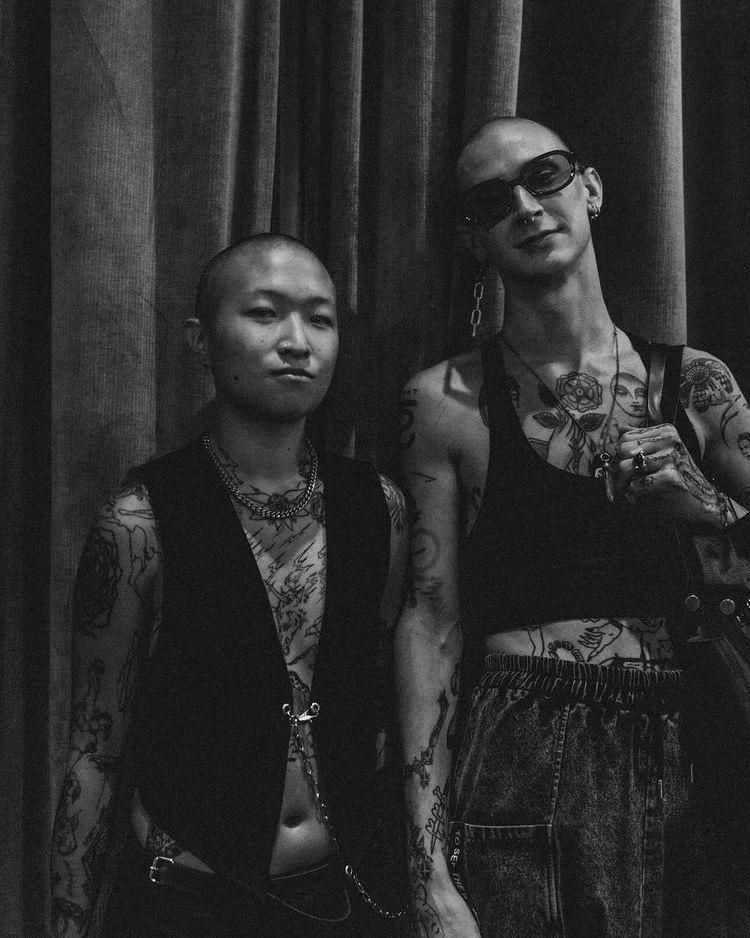

Coco and Indigo

West’s tattoo journey, like those of many stick-and-poke pundits of late, started during quarantine when in-person jobs were moved virtually. West was a copyeditor but got “really addicted to painting.” Tattooing also piqued her interest, as she wanted to get more but found it difficult to book appointments because of COVID. She ended up buying a couple of DIY single-use stick-and-poke kits. “How hard could it be?” she remembers thinking as she began practicing on her legs. She vacillates between pride and sheepishness. “I was painting like eight hours a day every day and just not doing my job.” She was soon fired, she explains with nervous giggles, and this was not a surprise.

A global pandemic, a mandated lockdown, sudden unemployment — these were the unexpected circumstances that colored the backdrop of the early stages of her transition. She was prolifically painting and tattooing close friends, but wasn’t yet charging for her stick-and-pokes. She picked up sex work to supplement her income. She’s now able to live fully off her tattooing practice but still sees the kinkier clients when she wants an extra swell of money.

During the pandemic, as she continued to experiment with her own practice, she was booking with other young queer tattoo artists, “building relationships but also gathering info” on the tattoo trade. West, who had previously gotten tattoos in traditional tattoo spaces, unknowingly stumbled into a pandemic-fueled underground tattoo community. “At first, I was like, ‘Oh, this is kind of ratchet. I guess I’m gonna lie on your bed,’” she says. “But it ended up being really nice. It feels more like hanging out with a friend than like... going to the doctor.”

This comparison is not unusual for queer tattoo enthusiasts entering traditional parlor spaces. “[Traditional tattoo shops] are really, like, cis-heteronormative spaces. You walk in and you feel judged. You’re on a bench with a bunch of other tables. People can look at you while you’re getting tattooed. It’s just stressful,” West explains. “As a trans woman, especially because I was starting to tattoo pretty early in my transition, I don’t really want to be in those spaces.”

Indigo and Coco, who are both nonbinary, have also had uncomfortable experiences in these machismo-to-the-max tattoo shops: being misgendered, pressured into choosing a larger size or continuing for hours without a break. Indigo tells me that they even “present a little more femme” when entering these spaces because “they see me as a woman automatically.” They look to the ground, pinching their lips into a light line. “Also being Asian…” they pause before concluding, “it’s just sus vibes.” Indigo looks to Coco for friendly reassurance.

Coco nods heatedly. “Putting their opinions on your body. You know, the judgment thing, like, ‘Why would you put that piece of shit right there?’” Coco and Indigo laugh, and Indigo chimes in, “Well, I don’t think it’s a piece of shit!” They add: “Creepy men coming over just lingering. Not even asking if they can look at the tattoo that’s happening. Then I’ll start watching them browse my whole body and make faces after looking,” “Like get the fuck away from me!”

Coco explains they’ve been very intentional with the tattoo shops they brought their business to while living in Chicago. “[They] were all femme-run. And I specifically went to female artists because I felt there was a lot more time, care and attention given.”

But when people want tattoos, especially when it’s an important part of their identity and how they self-express, they will brave any situation. West says, “I’ve had so many clients be like, ‘This space is so nice.’ And then they’ll tell you some horror story about going to a tattoo shop,” she says. Eyes widening, she tells me about a client who wanted top surgery scars covered; the artist didn’t know what top surgery was or how to treat the client with respect. “I’m like, yeah, that’s why this space exists.”

Zyra West

The room is warm and feminine, West filling the space with her sunny presence. “The tattoo process is sterile, but the environment is not.” She explains that she’s mindful of her clients’ behavior and intuits their emotions and body cues. If someone’s getting a tattoo in a more vulnerable spot, she will “always ask for consent around touching and will frequently check in,” offering breaks and comfortable positions. “I’ve been told by a good amount of people that I have a fairly gentle touch,” she says.

She explains that once clients feel the lightness of her stick-and-poke skills, she can “kind of feel the energy relax.” She adds: “I have way more clients fall asleep than I ever dreamed.”

I pour over her flash book: mermaids, breasts and devil horns. She laughs. “You can call it what it is,” pointing to the raunchy “Eat Me” inside an outlined heart. “It’s slutty,” she says, both of us breaking out into giggles. “Within the queer community, people don’t really want Sailor Jerry tattoos. The whole traditional American style just has a very cis-het man vibe,” West says. She clocks other queer people on the street purely based on their tattoos. “Whether it’s conscious or unconscious, [tattoos] are intentional. It’s a way to find your people.”

Pulling metal chairs into the center of the room with shrill scrapes, 31-year-old Coco and 27-year-old Indigo face me with cautious smiles. I’m curious how they met each other. They giggle, turning their bodies toward each other, sharing knowing glances. “So...” Coco starts. “Coming back from France, I made a point to find more queer friends,” Coco says, telling me that they had mostly straight guy friends when returning from Paris after a romance turned cold. “Indi just shows up and it’s like, oh, you’re also nonbinary, you smoke hella weed and you like tattoos!” Coco says, ticking imaginary boxes on their fingers.

Indigo nods and says, “I met Coco and saw how much passion they have for tattooing. It [was] inspiring and super dope to see. I worked a really shitty job. And they’re like, ‘Dude, quit your fucking job. You can tattoo. Your work is sick enough and your tattoos are good enough.’”

“My biggest thing about working in other shops is the pay. It’s always about the pay,” Coco says. Indigo nods in agreement. Coco explains that not every queer person can afford an hourly rate, often around $200 per hour. To them, it felt like robbing your own people. On top of this community betrayal, artists must set expensive hourly rates because the shops will keep nearly half of what customers pay. “At the end of the day, I’d just be like, ‘Oh my goodness I lost so much money,’” Indigo remembers.

While many artists pay upwards of 50% of a tattoo's price to the studio, Indigo and Coco can pay for the studio, equipment, and kitschy hot pink blow-up couch, all the while reinvesting in their monthly rent. In this underground Brooklyn tattoo scene, artists are in control of their time, profits, and creativity. In their own spaces, Coco and Indigo can set rates per flash or custom piece and have conversations with their clients about what they can and cannot afford.

“If you’re willing to pay for a piece of my artwork to be on your body, the least I can do is give you time for that,” Coco says. “So opposed to the shops that I’ve worked at, I feel like these spaces allow me to really have time with my person. We can take an hour-and-a-half break and get lunch, shoot the shit, smoke one if we want. Just chill —” Indigo interrupts, chiming in, “The amount of times Coco’s brought a guest out!”

Queer joy and sometimes tearful intimacy shared between the artist and client is a sustaining aspect of this underground community looking to redefine tattoo culture in New York. This burgeoning underground scene, revived during the pandemic, uses Instagram, word-of-mouth, and a network of peers to draw in clients that appreciate the basement-or-bedroom makeshift intimacy between artist and client. The growing accessibility readjusts our knee-jerk reaction that to get a tattoo you should stumble into your nearest tattoo shop. If you’re willing to do a little bit of digging, you can find the right artist and space for you.

Coco and Indigo's studio

“With the American [tattoo] system the way it was, I just didn’t really see a space for myself. But the American traditional [tattoo] system has started to decline a little bit,” Coco says. “Maybe this is the start of a new generation and a new approach. Then queer shops will start to take over a little bit and not just turn it into another money machine.”

Indigo nods. “I think the next step after this would be opening up something else. Like learning how to create a space and somewhere where we can afford [to bring in] other queer artists,” Indigo says. “This tattoo community that I’ve found has been crazy. I didn’t know that something like this existed.”

Images courtesy of Coco, Indigo, and Zyra West