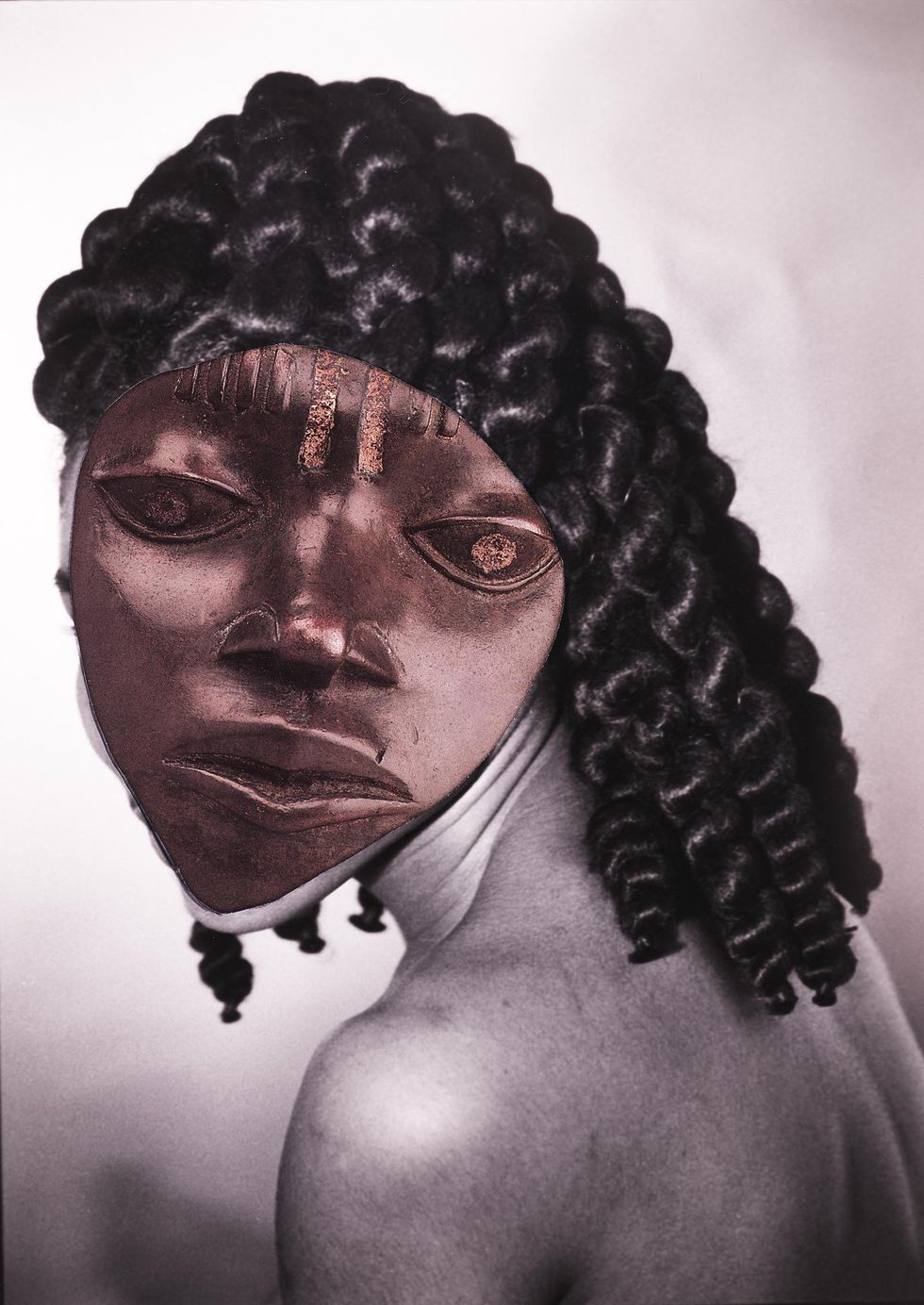

“I know a diva when I see one,” Coreen Simpson, legacy fashion photographer and jewelry designer, remarks on her series, "Masked Nude," currently on display at Fotografiska's new exhibition "BLACK VENUS."

"BLACK VENUS," which opens to the public today, May 13, and is on view through August 28 at the New York photo gallery, follows the lineage of Black beauty through over 30 contemporary works dating back to 1975 and includes a selection of archival imagery between 1793 and 1930. The exhibition investigates the global, cross-generational struggle for reclamation of the Black female body, under the compounding pressure of its fetishization. Featuring works from notable artists like Simpson, Renee Cox, Carrie Mae Weams and Kara Washington, "BLACK VENUS" celebrates Black women exactly as they are.

“This exhibition is an autobiography of the Black woman,” curator Aindrea Emelife says. “Not always nude, not always sexualized, exoticized and fetishized for the white male gaze. The work in the show uses humor, desire, history and at times melancholy to tell stories about the personal and collective history of the Black woman.”

At its center stands three historical reference points of Black beauty: the “Hottentot Venus,” Saartje Baartman, an enslaved woman who was toured around Europe by Dutch colonizers for her non-Western body type; the “Sable Venus,” a reimagining of Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus" used to romanticize the slave trade; and Josephine Baker, who’s tactful navigation of sexuality and politics gave rise to a new archetype of Black women as the “Jezebel.”

But "BLACK VENUS" moves beyond the gaze and fetishization — looking towards current artists who capture Black beauty, oftentimes in their own likeness, in all its varied forms.

“I created a jewelry design that Black women didn’t know they wanted,” says Simpson, whose “Black Cameo” brooch re-imagined Chanel’s famed Cameo style for Black women, who were delighted to wear their own image as a badge of honor. “That’s my legacy as a designer, because Black women didn’t have a reflection of themselves in America.”

For Simpson, whose career runs longest out of all the contributors, "BLACK VENUS" is a chance to celebrate the women who saved her life. “I am a person that glorifies my culture, especially women, because women have saved my life in my 80 years on the planet,” she says. “I photograph women that I think are engaging and enchanting. I’ve been following that all my life as a photographer.”

Growing up as a foster child in Harlem, following her parents' failed marriage, Simpson notes that she's had the fortune of witnessing so many manifestations of beauty and credits her social worker, Miss Foster, as being her first reference point. Captivated by her dark complexion, and the way she put herself together, down to her black suede, and pink pom-pom adorned booties, Simpson felt she could see herself in Miss Foster, or at least who she hoped to become.

“Every time she walked down Pacific Street, she turned it out,” Simpson gushed. “That’s what I aspired to be like, glamorous and fabulous.”

As Simpson's career took off, she met famous faces — like Naomi Sims, who intentionally kept her lit cigarette out of frame during a photoshoot so young girls wouldn't mirror her behavior — each of whom helped her gain her own sense of beauty, beyond the physical body. “Beauty can do that for you,” said Simpson. “It just takes away all your tiredness from your body. I was, like, lifted.”

"BLACK VENUS," too, goes beyond the physical and asks the viewer to see what's within. “Some of the photographs see the artist pose as historical Black women. Sometimes recreating the typical reclining nude poses,” shares curator Emelife. “Their gaze is not subjective — it is powerful. They stare back at you. You see them looking at you looking at them — the complicitness in the gaze is so clear. It's like a dare, keep looking, we've always been there, we see you, now see us.”

"The Hottentot Venus," "The Sable Venus" and Josephine Baker are no longer the only archetypes of Black femininity. Now — thanks to exhibitions, like "BLACK VENUS" — we're able to see the influence of someone like Miss Foster, alongside the more public Naomi Sims. We're able to recognize the interwoven cycles of trauma and triumph that characterize Black Beauty. "BLACK VENUS" is a distinct, and intentional effort to end depictions of black femininity as a commodity and, instead, give thought to the history that courses through each woman, and that which they create.

“I think of Eartha Kitt crooning "I Want To Be Evil,”’ said Emelife. “We can be so many things when we are in charge of how we are seen.”

Photos courtesy of the artists