Film/TV

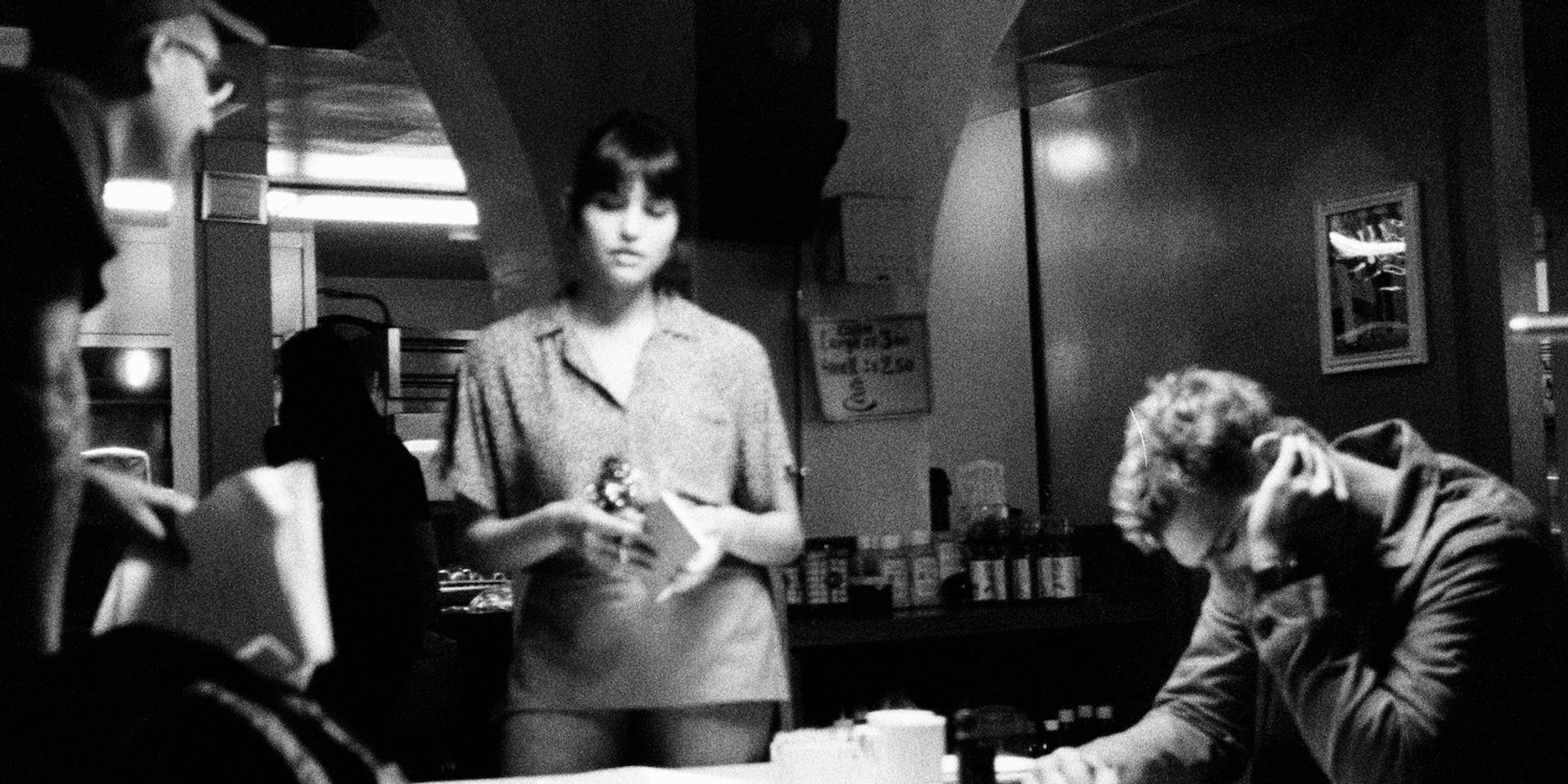

Watch This Short Film Starring Paris Hilton and Nasty Cherry's Gabriette

by Rose Dommu

06 May 2020

While he spent the early years of his career making music videos, Ramez Silyan always wanted to be a narrative film director. It wasn't that he didn't like making song visuals, but he never felt like he was telling his own stories. "It was something you were sharing. It never was yours," he tells PAPER. "Music videos are something that it's the artist's first, even though it's just as much yours in a way. It's a collaboration, but nobody else really sees it that way."

Related | Paris Hilton's Shiny Pink Perfume Legacy

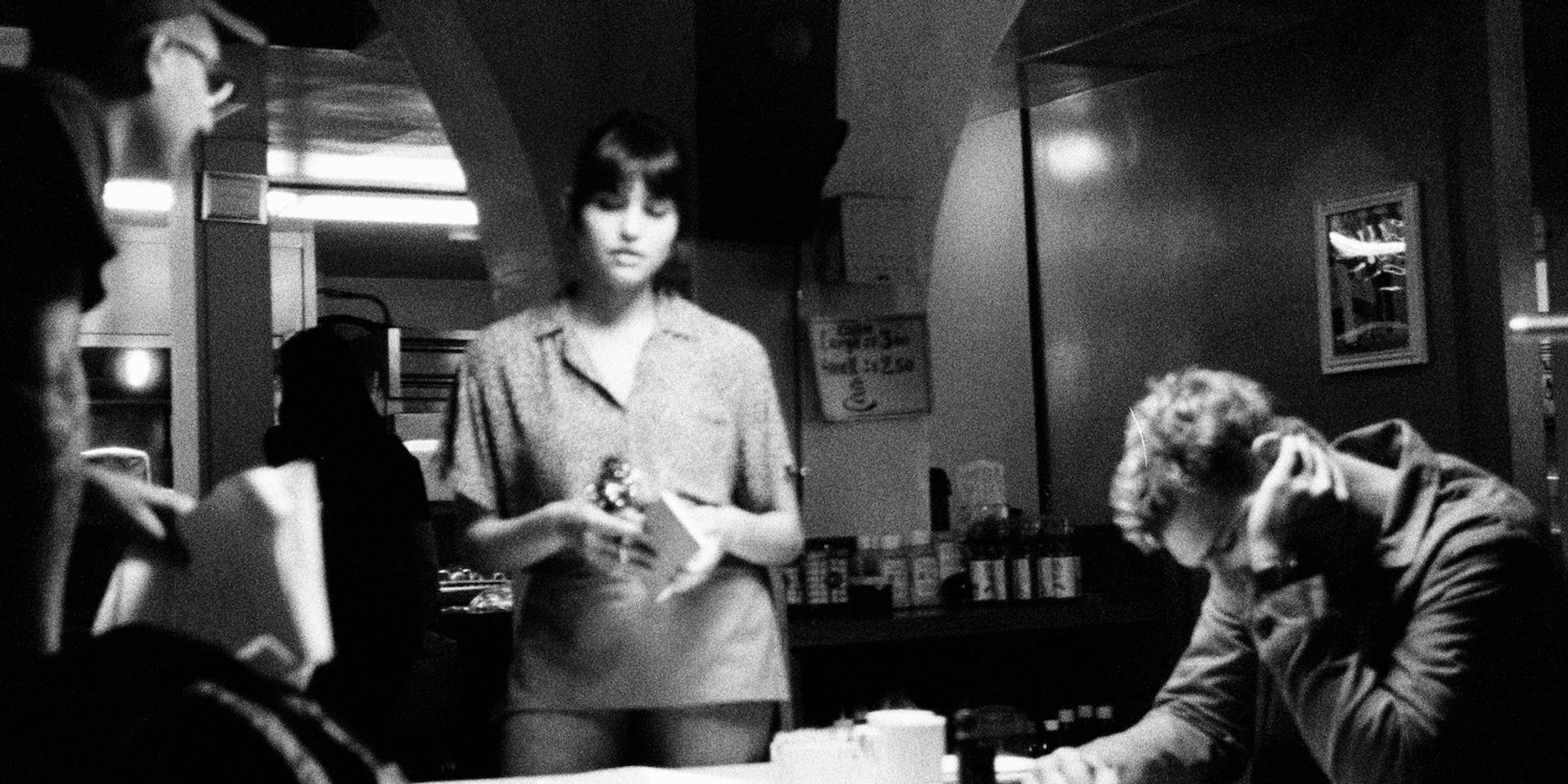

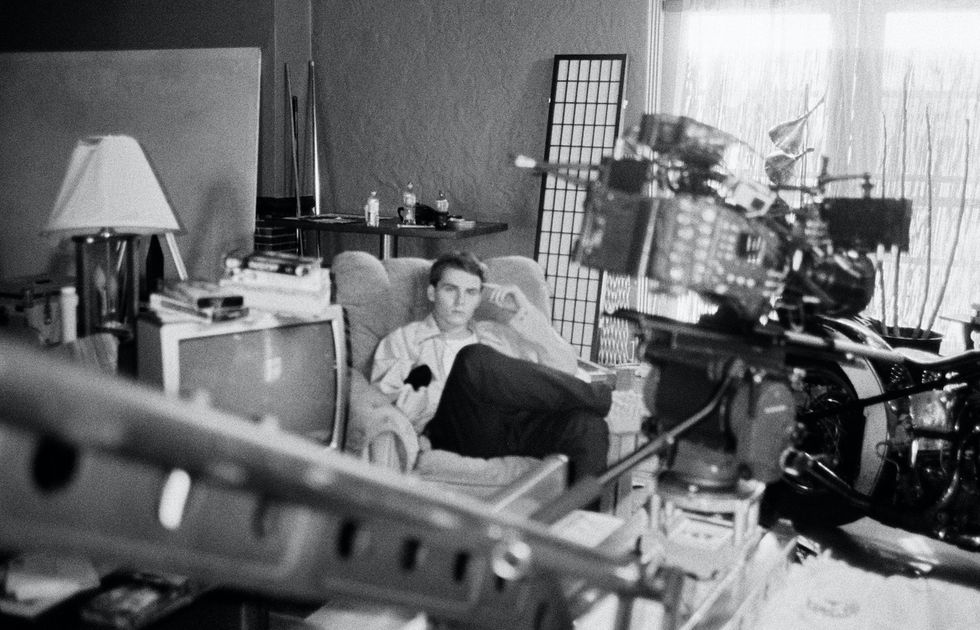

Working in music led to Silyan's feature directorial debut, the Lil Peep documentary Everybody's Everything, and finally he decided it was time to make something that was just his. The result is SORRY (or what could have been), a narrative short starring The Leftovers' Chris Zylka, Nasty Cherry singer Gabriette Bechtel, and — gag of all gags — Paris Hilton in one of her rare acting roles.

How does a filmmaker go from making music videos to directing Paris Hilton in one of her first roles since House of Wax? PAPER spoke with Silyan to find out.

The best music videos often bring to life the story of the song — so did directing music videos leave you well equipped to make a narrative short?

I would say yes and no. My favorite music videos definitely do that, but they're always to songs that just kind of evoke emotion. They have this loose story that kind of matches the way that the song feels. I agree that helps, but you don't always get a project that's sort of meant to do that.

A lot of the times when you're making a music video, it's about making sure the artist is making a statement to the public, or to their fans, which makes a lot of sense. They're trying to promote their music. Whereas as a creator, you're like, "Oh, I want to get into this niche story." But there's always pushback. It's not the norm anymore. Every project is so different, but I definitely saw it as a training ground. I definitely saw it as a place to play with toys that I couldn't afford, play with these cameras I could never put my hands on unless I paid somebody for it, and I was never going to be able to afford that myself, so I was like, "Oh, every time I do a video, let's try something new. Let's get a Steadicam. Let's be able to hire a colorist or use this camera that is like $50,000." So, that's the way I saw it as practice.

Your first feature project was the Lil Peep documentary, Everybody's Everything. That's another project where even as the director, you are telling someone else's story. What tools did you pick up from that to then start bringing to creating your own stories?

Well, with Everybody's Everything, it felt like a project that I sort of naturally just fell into. I worked with Gus, with Lil Peep, on several videos, and we had plans of working on more. Some of that footage you see, I actually filmed personally in Russia, and Europe, and it just felt like I knew the story and I knew — let's say I knew a lot of my part of the story, and I needed to know more. It felt like something that I cosmically had to be a part of.

Not to say that Everybody's Everything wasn't driven by me, but it was definitely driven by the need to want to tell people his story, because he didn't really get the opportunity to do that himself. And I think that he would have. I think that it's almost a shame we had to make the film, but it felt like the right thing to do. That kind of sums it up.

So, I've always just kept pushing to try to tell my stories, I have so many stories I want to tell, and nobody's just going to hand me a big check and go, "Hey, make whatever you want." I have to show them that I can tell essentially someone else's story before they'll let me tell mine. Or tell ones that... I have a script about my dad, and people aren't going to pay attention to something like that until there's an obvious reason. "Oh, well, you know, we want to hear any story by you because you've proven you can do it. You've proven you're a storyteller." And I think that's how you become a director. You have to prove that you can tell a story.

There's this give and take between can you afford to tell the story, or does somebody want to pay for it. Unfortunately, that's the hard lesson.

How personal is SORRY?

It's pretty personal. My girlfriend's name is Sydney, and so the girl's sort of named after her, and also in some ways a tribute to Sidney Lumet, who's one of my favorite American directors. But there's definitely this personal aspect to it, because me and her have been together for 12 years now, and not to think of the story as being — I don't see the story as being depressing. I sort of see it as being hopeful in the sense of like — you work. I think that me and her both work really, really hard at our professions. She works in fashion design. I'm in this. And I think sometimes we don't slow down and look around, and wonder, "Are we accomplishing our goals? Is this what we want to do? Where do we see ourselves in 10 years if this trajectory stays the same?"

And I think that I do have a tendency to apologize a lot, even when it's unwarranted, so that's something I've always sort of tried to self-reflect on.

The film seems to really be about people who are stuck at a crossroads and facing what their lives could be.

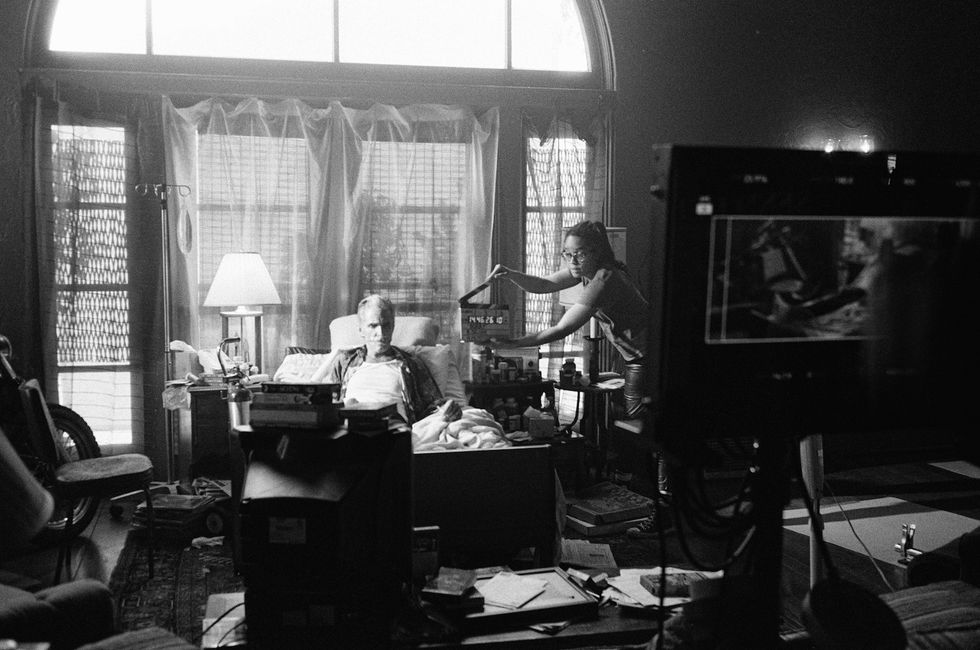

That's exactly the feeling, and I set it in this idea of a relationship, because that feels like the most common place for somebody to feel that. But another big inspiration for that feeling was I was working on this project that hasn't really come to fruition yet, but it's about these old outlaw bikers who used to run Venice Beach, and how it was going around with a peer of mine just interviewing actual bikers, and the older character in the short is directly inspired by one of those people that recently passed away. But there was just something about the way that they would talk about their lives, like they were so carefree, it didn't seem like they worried about the future in that way. They were just like, "We're going to do whatever." Like literally, the story of letting the dogs out of the pound [that's told in the film] is a story he told me.

I envied that idea that you're going to do what you're going to do no matter what, and you don't care if somebody sets the clock back and you're just doing it over and over and over again every day. Every day you're going to go let the dogs out, and somebody's going to catch them and put them back in. You don't really care if that's the outcome, because you enjoy the process. And yeah, this film is sort of envying that outlook. I don't think a lot of people today, given the way our society is set up, feel that way.

It's interesting to be releasing a work about repetition when we're in this moment where everyone is stuck in home and living these lives that feel really repetitive. How does it feel to be creatively in sync with that moment?

It's so odd, because as I mentioned earlier, the days just blur. There's no such thing as a weekend anymore. It's like there's no anchor. Nothing is anchoring time besides the sun, and it's just really weird. And that's one the reasons I really wanted to put this out, that feeling sort of setting in, like I think people are. I was reading an article about people having weird dreams during quarantine, and it just felt like the time.

I wanted to put this in a film festival or something, and then I was like, "You know what? Let me just share this." Because people are at home and it feels like the right moment, and maybe people will see their own lives in something like this. Because none of that, none of the film is outside, either. It's all people inside talking.

One of those people is Paris Hilton, who also produced the film. How did she become involved?

The first short film that I did, I had worked with Chris Zylka, and we had just met randomly through a mutual friend, and I told him how much I liked his work in The Leftovers, which he was on at the time and which I still think is a phenomenal show. Maybe very eerie to how people feel today with the end of the world. So I met him back then, and we had done this first short that was like my very, very first narrative, and we just kept in touch. We had worked on certain things here and there, and when I had this script, we were talking and he just asked if I had anything. And I sent it to him. He was like, "Hey, we want to make this."

I was like, "Oh, what do you mean?" He was like, "Oh, Paris likes it, too. She wants to be in it and we want to help you make it." Which was awesome, because it's like there's not a line out the door to help make a short film. Nobody's like, "Oh yeah, we want to." It's not a huge money making endeavor. It's sort of like a statement, like, "Hey, we're going to put as much money as we have into this. We're going to pull together favors. And we're going to make an expression sort of outside of the market." Because there isn't really one. The best case scenario with a short is getting a bigger next job, or recouping a little bit of money. I don't think they've ever really made any money.

What was it like to direct Paris Hilton?

She is Paris Hilton — she controls a room. She comes into the room and she's very nice, she says hi to everybody. And you don't get started until she's ready to get started, because that's just the way it goes.

It was crazy. Kind of weird and surreal to just be like, "Okay, everyone's ready. Everyone has their places. Let's go." And yeah, it went by so fast. We shot only two days. She was only there one day, but I think that's the sad part is I didn't get to live in it. It almost feels like I was moving and now I'm trying to see myself back there, rather than being able to remember it clearly. There was so much anxiety involved just directing.

Do you see this story as a closed loop, or is it something you'd want to revisit as part of a larger project at some point?

That's a good question. I never thought about expanding it, but I do think the themes would be something that I would definitely bring up again. Just because I feel like the short is just a way to start playing with an idea, and it's very difficult I think to fully reach its potential. This almost piques your interest, and there's so much more to go into, so I think dramatically, yeah. I don't know if the exact setup with the same exact characters, but maybe.

Are you feeling pressure to be creative during quarantine, or are you more focused on just getting through it?

Both. I mean, when everything first started unfolding, I definitely took my two-week, "I'm just going to do whatever makes me feel sane," moment because everything turned upside down. Now I'm still in the process of trying to structure myself in a more productive way, but mentally I'm definitely there, I want to come out of the other end of this having done something I'm proud of. Whether that's writing a pilot or something, or just... I definitely want to stay productive.

But that being said, I don't think people should feel the pressure to make something great in a time where they might not be able, they're worried about being able to pay their rent. We're all just trying to get by, and that's the most important thing. If you make something along the way, that's wonderful, it's beautiful, but I don't want to — me, myself and other creative people shouldn't feel like — when you start to feel that weight of everybody's collective consciousness, I don't think you're going to make anything that incredible. Everybody's looking at creative people, which is interesting, because maybe we get overlooked a lot. But now, in a time when everybody needs a beacon, the pressure's on.

Photography: Sydney Szramowski