Oscar yi Hou Keeps It Real

By Petala Ironcloud

Nov 14, 2024

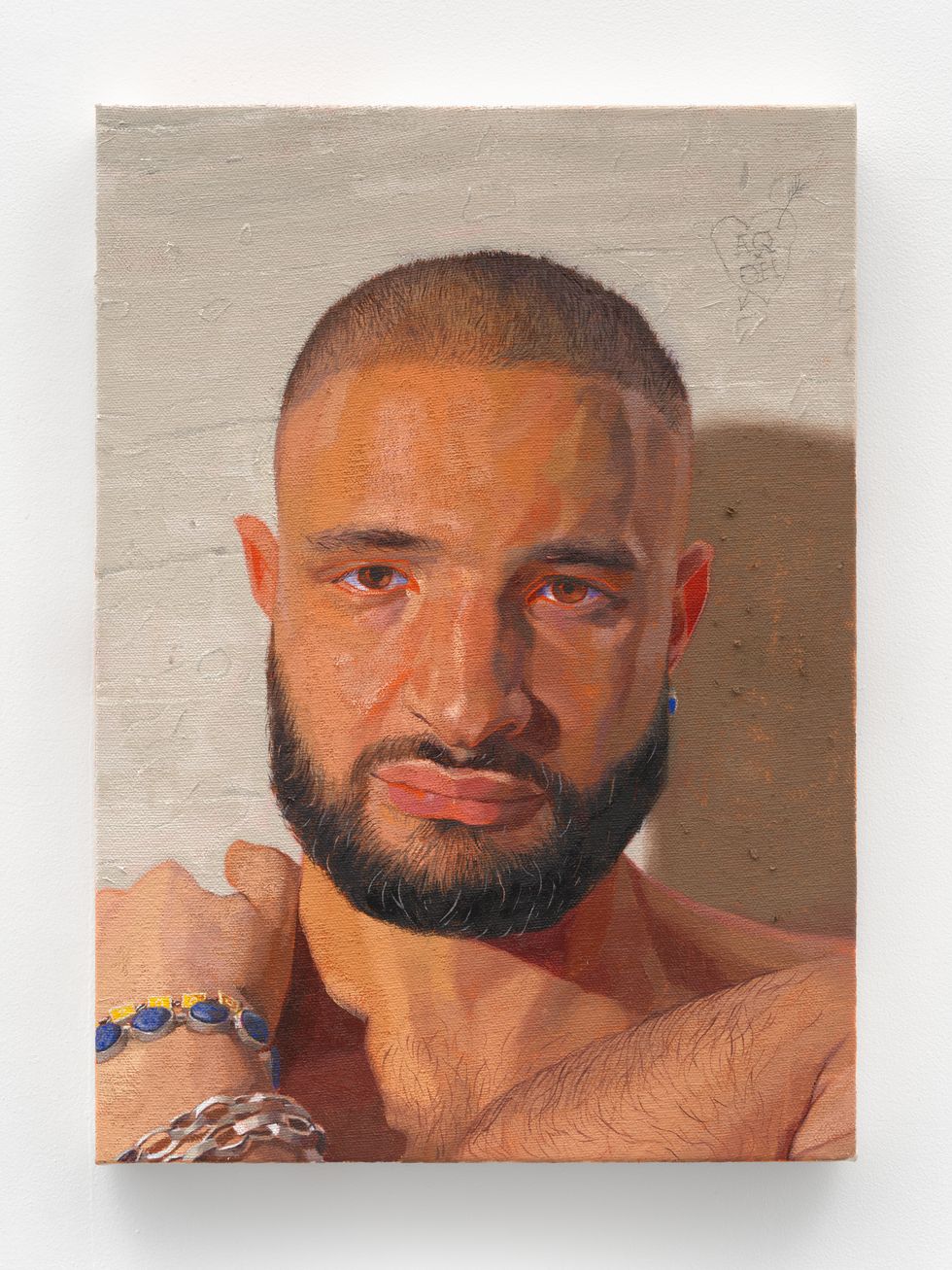

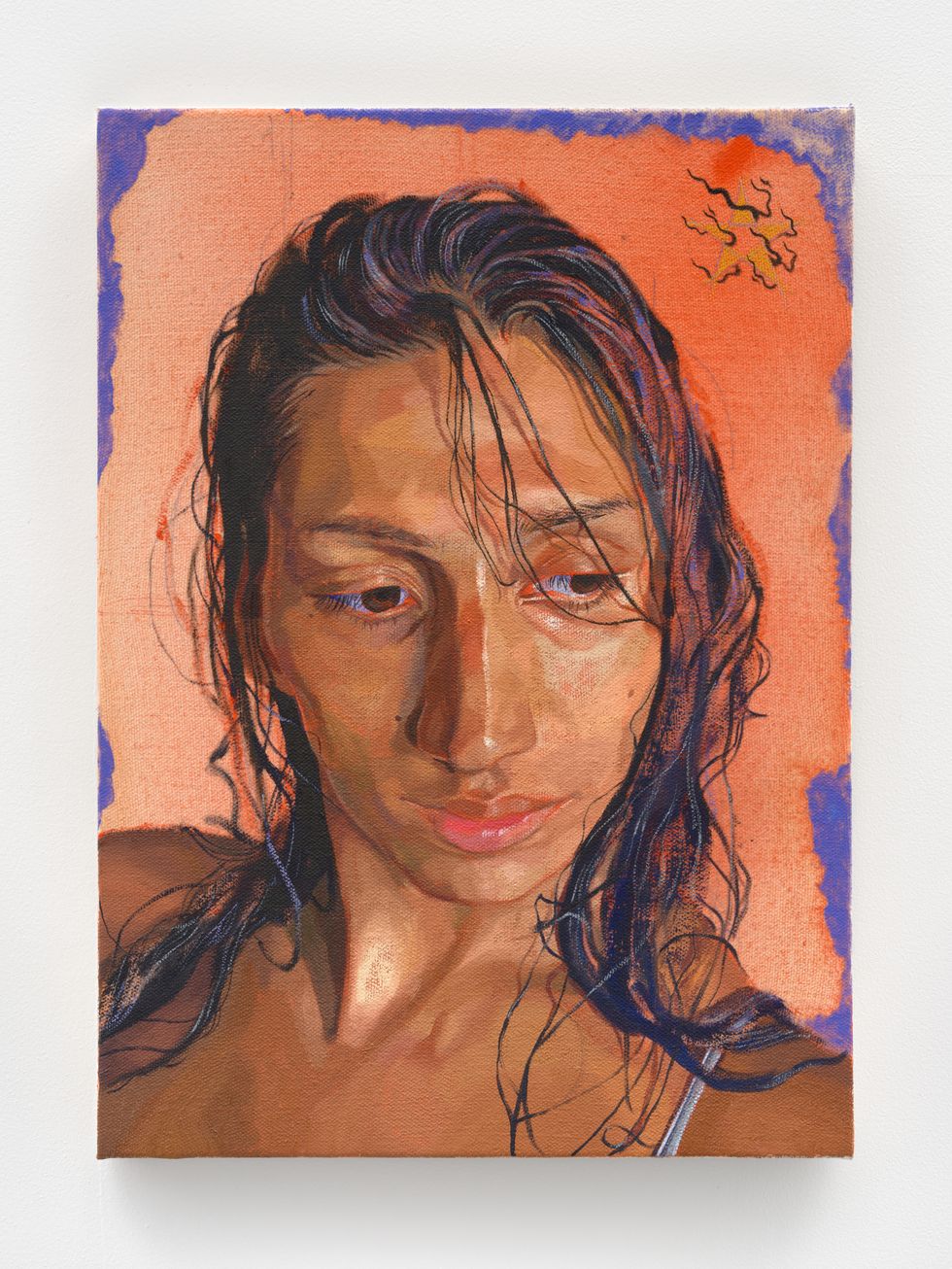

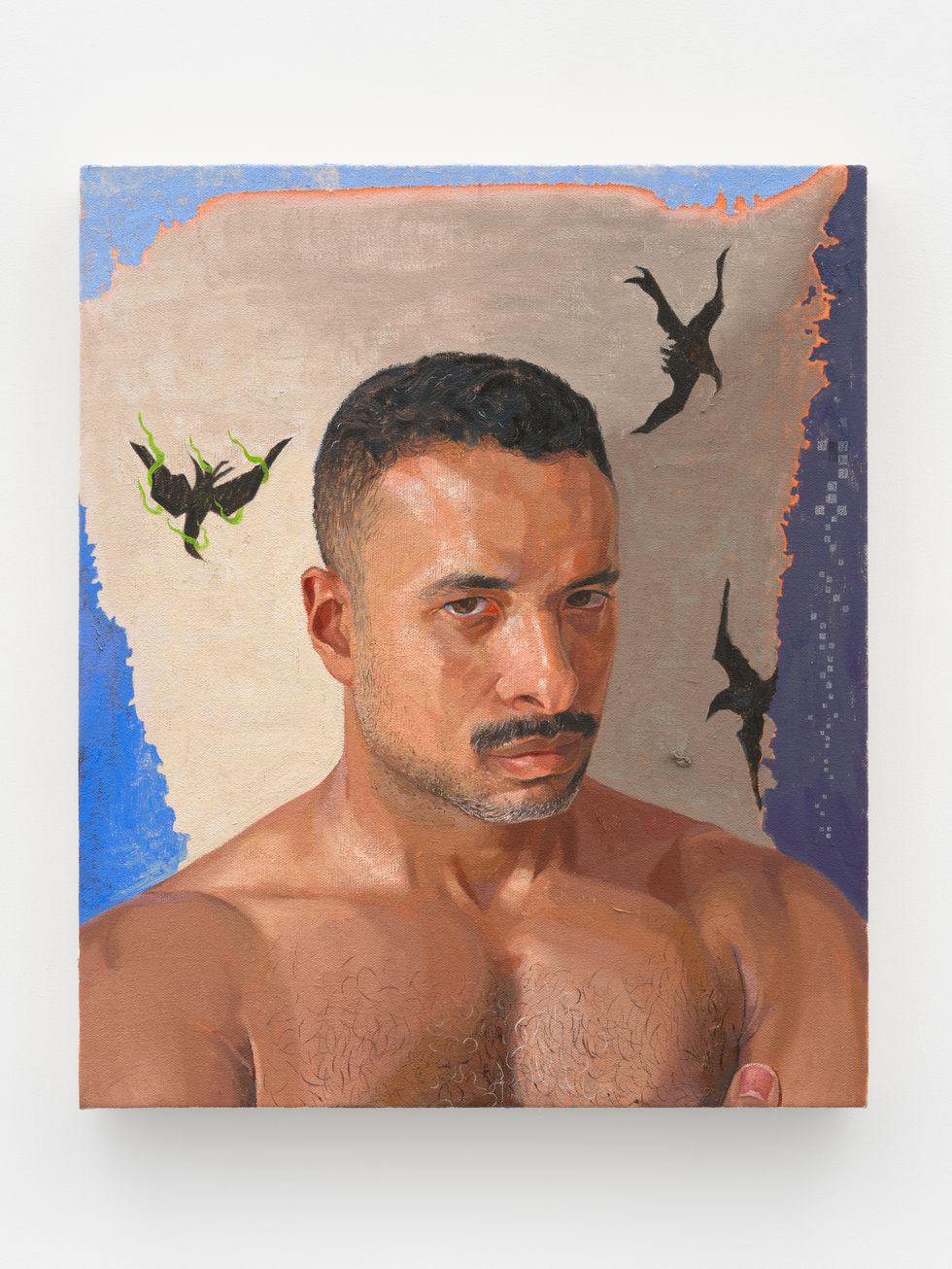

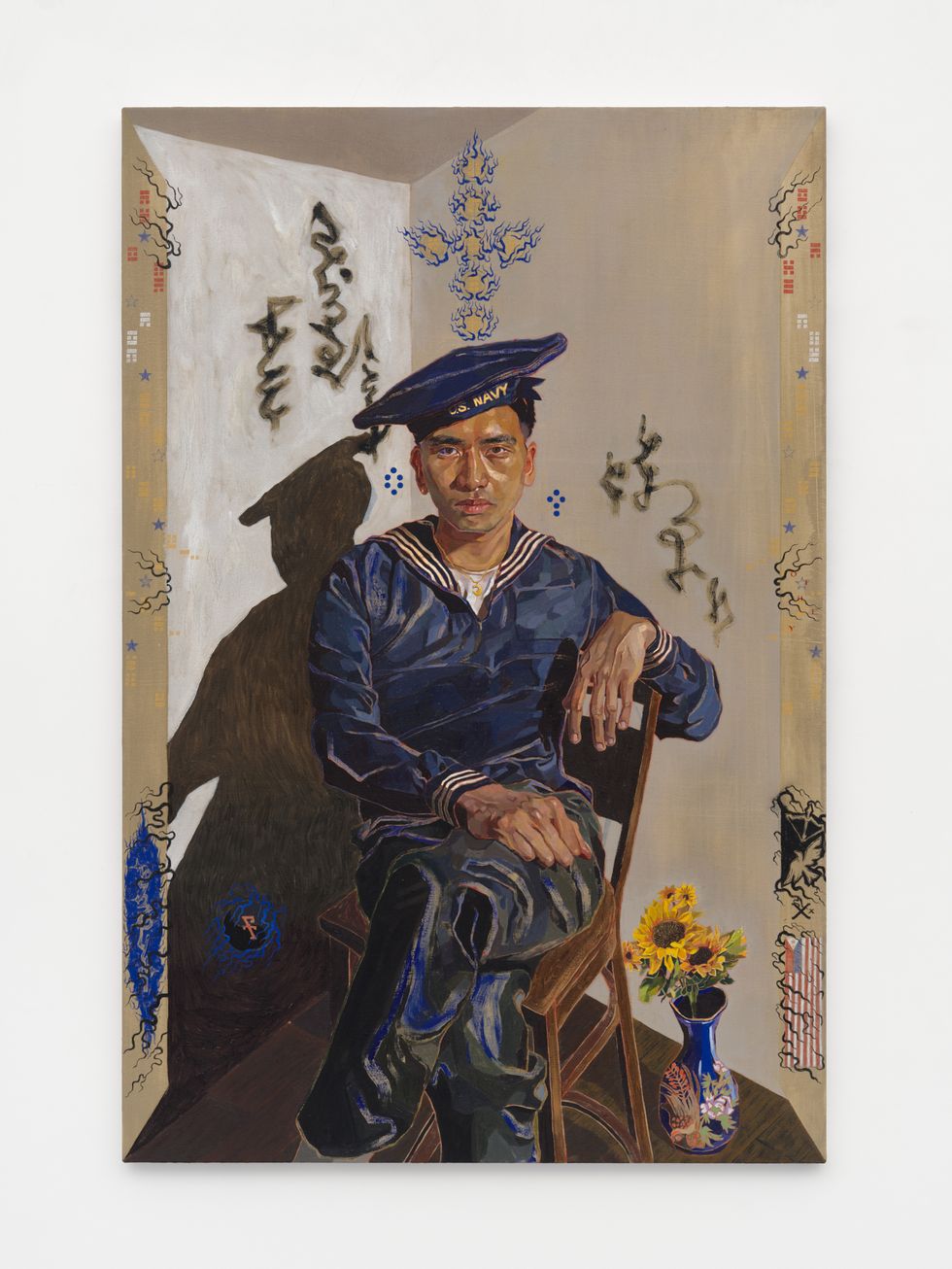

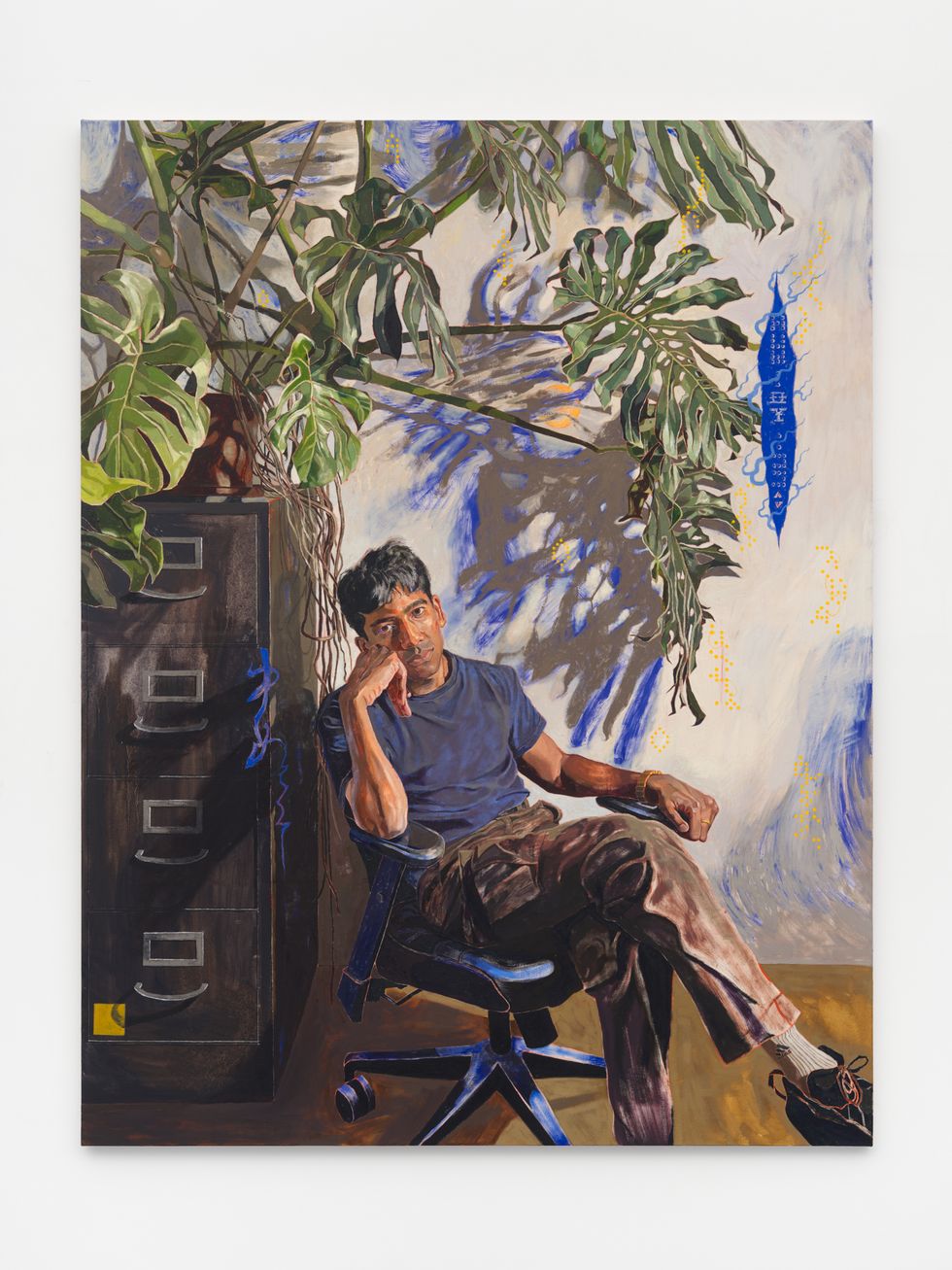

The posturing of Oscar yi Hou’s cosmopolitan models confers an unexpected intimacy upon the primarily masculine figures in his portraiture. Though yi Hou has reckoned continuously with gender performativity since his meteoric rise in and after college, like the essence of drag, he doesn’t seek to dismantle the social construction so much as play with it. A direct gaze and myriad semiotic gestures bedazzling the borders around his subjects two or three years ago has given way to semi-profiles and anterior views, restrained symbolism and lustrous hand and facial details. Supple cheeks enrobed in assless chaps, a secret agent triptych and a limp-wristed, cross-legged Navyman also feature his toying with sexuality.

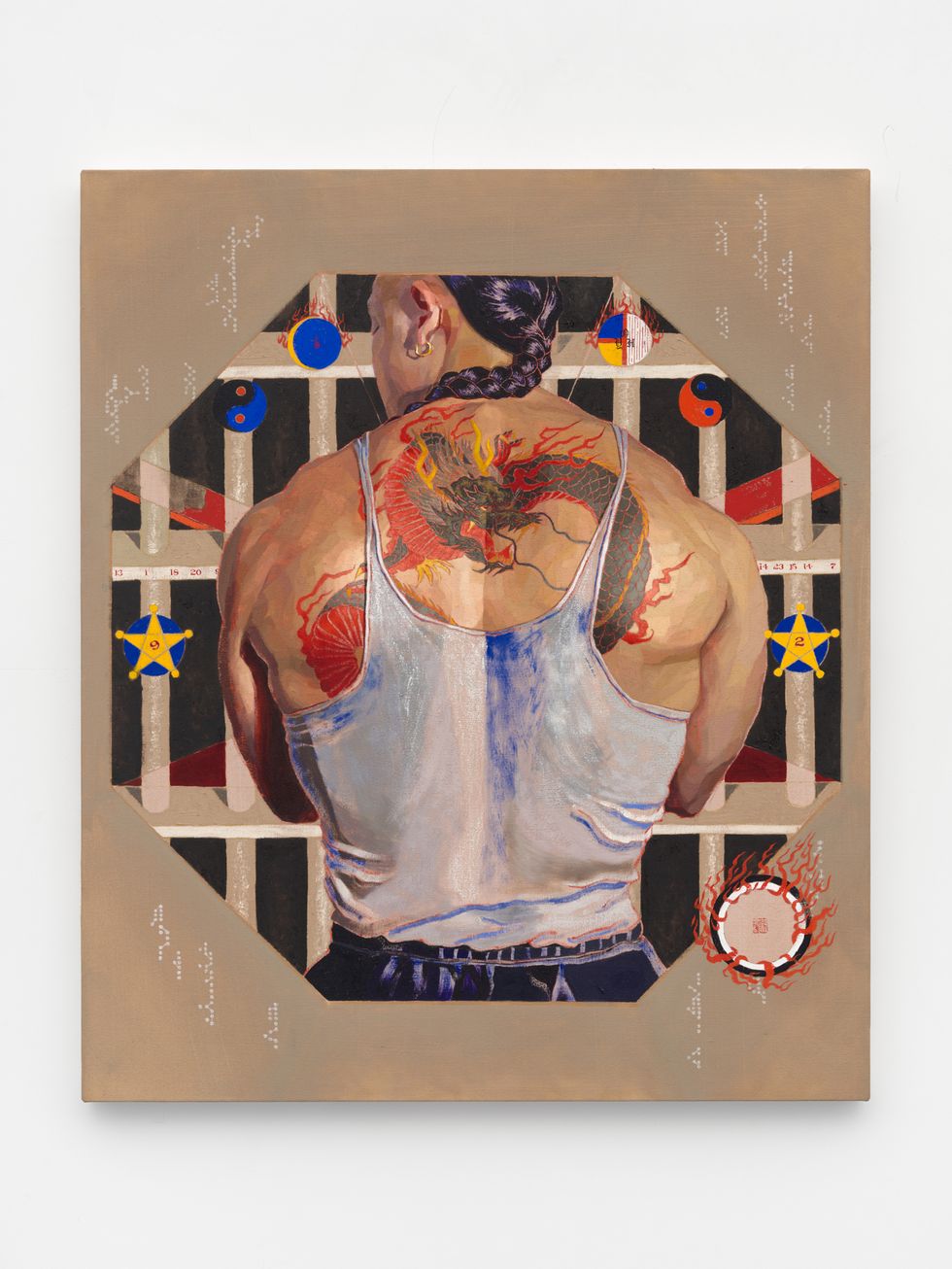

The recurrence of gender and sexual stigmas in the American political landscape of late make yi Hou’s puckish barbs all the more subversive. At James Fuentes Gallery in New York City, he hung his show The beat of life with the BTM-heavy painting “Coolieisms” centrally visible from the street, “inviting in the riff raff,” announcing its directness and receptivity. The exhibition’s soft power repudiates recent amplifications of conservative desires, fears and anxieties transposed onto queer people, particularly queer and trans people of color — a displacement rooted in fear and fantasy gender theorist Judith Butler calls the “phantasm of gender.”The triptych “Birds of a Feather” is agentic in two ways, displaying the artist and two dear friends as secret agents, and these figures jovially and self-determinantly engaging with stereotypes. Yi Hou is designated “Agent Crane,” reflecting the recurring motif in his oeuvre based on his Chinese name meaning “one bird song.” The middle panel shows Amanda named as “Madame Butterfly,” alluding to Puccini’s opera and perpetuating the notion of subservient Asian women willing to do anything to serve the dominant force, in this case the Western man. Sasha on the right-hand panel is referred to with the moniker “Dukes Dragon” refers to daisy dukes and is a play on words, twisting the sapphic “dyke” into “duke.” Together, these multidimensional renderings embody several dualities — masculine/feminine, homosexual/sapphic and signifier/signified — thickly contouring the human experience and leaving the stereotypes inanimate and effigial.

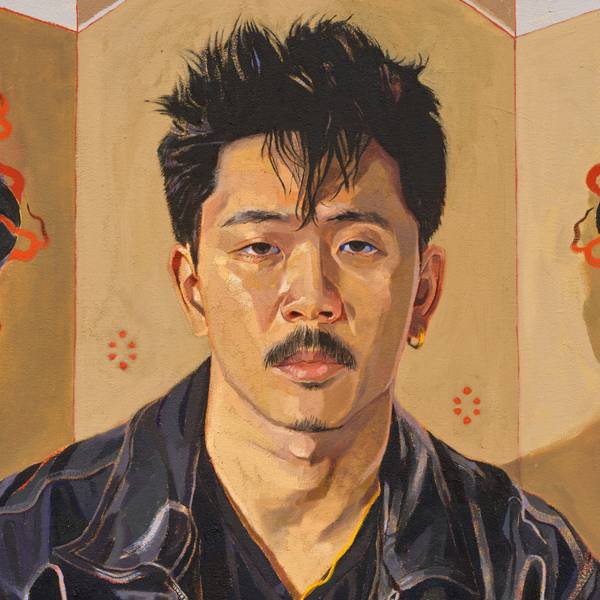

Between his first James Fuentes show, headlining at the Brooklyn Museum and his current display, the juxtaposition of his portraiture puts its development into sharp relief. “Self-portrait (21)” thrusts upon the viewer yi Hou’s youthful panache, emulating Van Gogh's bold, directional brushwork and brightly saturated oil-based palette. Its colorway conveys an ebullient femininity suggesting the transient nature of masculine and feminine energy, perhaps especially in youth. Conversely, “Self-portrait (25)” uses gouache and oils, producing darker, richer colors and material qualities. The shift in ethos over time may appear purely external but perhaps shows maturation that is natural with age.

“It’s funny that as I feel less pressure to present professionally and precociously, my painting becomes more refined,” yi Hou tells PAPER, adding, “When I was younger, my youth was such a big deal, especially to the press, but now it's gotten old.” His earlier work was more colorful, frenetic and loose,reminiscent of Mattise’s colorscapes and the blurred gesticulations of Van Gogh’s “Wheat Field with Crows.” His seated subjects remind Liu Xiaodong’s Xuzi at Home, while the perennial and at times repetitive emblems perhaps drew from Tibetan Thangka scrolls and Qiu Zhijie’s Writing the “Orchid Pavilion Preface” One Thousand Times.” But now his high-frequency colors and sigils have slowed to a more efficient beat, the color red remains an intense and culturally significant hue, evoking sex, politics and violence.

The crane is another connecting theme, referencing yi Hou’s name, the meaning of which originates from a fragment of a Chinese idiom: Once flies, this bird will fly high into the sky; and once sings, it will amaze and startle everyone. While an imperfect translation, its nominative determinism corresponds to yi Hou’s overnight success, even before completing college showing in Manhattan’s Lower East Side at the James Fuentes Gallery at 21 years old in August 2021.“The star is a multivalent symbol of American states, communism, sheriff’s star, a symbol of merit. It’s complicated,” yi Hou says. The deputy’s star embedded in “Cowgirl of Connecticut” and “Birds of a Feather” stands out today, imbued with visceral meaning in a seemingly lawless political climate, drawing a through line from the “wild West” to now. “As French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan said, “the signifier is an acoustic image,” in this case, the star, and “the signified is the concept,” unstable and often slipping under the signifier. At this moment, our view of the star as law is obscured.

Visual authority continues to be represented in his sophomore James Fuentes show by way of masculine figures. “The function of masculine figures differs now, as opposed to my more confrontational Brooklyn Museum piece, ‘Coolieisms, aka: Leather Daddy's Highbinder Odalisque,’” he says. He continues, “The ass painting is facing away and is more receptive — you’re put on display, the way masculinity in the butt and dragon tattoo paintings are rendered; there is a bit of scrutiny.”

What is more examined than the face? Yi Hou has leveled up his investment in intimacy through his closer study of physiognomy. “I love painting faces! It’s so pleasurable and interesting,” he exclaims. Expounding upon that, he says, “Every stroke on a face can totally change the meaning,” surmising that the same holds true for larger pieces.

Ironically, he claims with a new self-portrait in process behind him on Zoom: “I care less and less about what I look like. In this one, I am wearing flip flops and gym shorts. I am literally just painting what I would normally wear.” Despite his modesty, his autoportraits increasingly convey a bullish quality, as well as a tension, shared with his other subjects, between hedonism and self-contemplation.

“I have always known who I am. I keep it real. And I have had the privilege to express this in my practice in a multitude of ways, academic and artistic,” he says, asserting consistency and integrity. He adds, “I really value my relationship with other people. I love my friends and family.

Yi Hou’s work personifies a rebuke of heteronormative asymmetry in the relationship between identity, masculinity and femininity, which his work, in particular, deftly displaces onto his subjects whatever their gender.

Photos courtesy of Oscar yi Hou and James Fuentes

Related Articles Around the Web

MORE ON PAPER

ICONOS: Pepe Aguilar, El Oficio del Tiempo, la Voz del Silencio y el Peso del Legado

Español

Jan 19, 2026

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October

Entertainment

Matthew McConaughey Found His Rhythm

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

30 September