Are you hallucinating or are you seeing the same face everywhere? You know the one. Highly sculpted. Quasi-"exotic." Suggestively cyborgian with equidistant almond eyes, '90s-supermodel high cheekbones and a poufy cupid pout. Dubbed "Instagram Face" in a New Yorker article by writer Jia Tolentino, it's an exactingly symmetrical look facilitated over the last decade by high-tech advancements in digital facial-tuning filters and injectable facial fillers, aka tweakments, aka the minimally invasive cosmetic procedures that have made Botox and Juvéderm household names. Filters and fillers.

Though this chiseled face devoid of smiles, frowns, furrowed brows of worry or concentration and wrinkles is primarily found on women, it was, in many ways, a face forged by men. As of 2018, 85% percent of board-certified plastic surgeons in the US were male, while 92% of their patients were female. Meanwhile, Facebook, which owns Instagram, home to some of the most popular filters behind these trends, has a tech workforce that was, as of 2019, 77% male.

Related | My Year With Big Lips

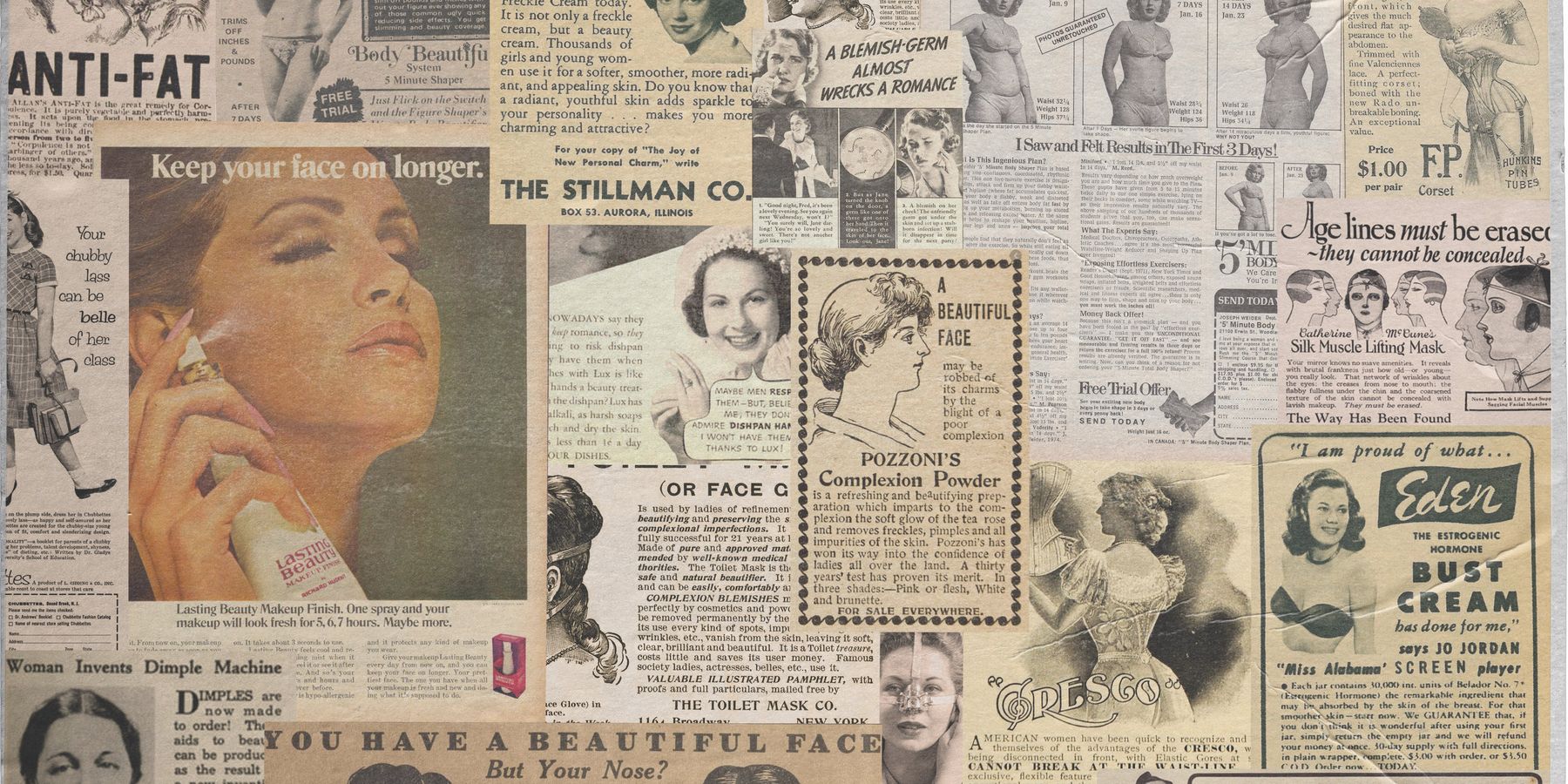

Historically, this "Oz behind the curtain" dynamic when it comes to "ideal femininity" is not new. From 1950s advertising executives brainstorming buxom, button-nosed visions of domesticity to 1980s filmmakers placing a prepubescent Brooke Shields in The Blue Lagoon's thinly veiled mainstream erotica, men in positions of power have consistently manufactured the American beauty construct.

And, like any functioning ideology, that construct has mutated to mirror its moment. The face of the 2010s — indeed, the supposedly ideal face at the core of the beauty paradigm for eons — has often relied on an essential recipe that Dr. Andrew Jacono, a prominent New York plastic surgeon and author of 2019's bestseller The Park Avenue Face, likens to the perfectly balanced proportions reflected in the wings of a butterfly or the gothic cathedrals of France. But remember in the early '90s when we sea-changed seemingly overnight from the flawless buoyancy of Cindy Crawford to the fucked-up teeth and waifish "heroin chic" of Kate Moss? Apart from the golden ratio, there is another beauty truth we could probably all agree upon: The trend pendulum eventually swings. Does that mean that we're in for a face envisioned by women? And, if so, what would that face look like? Could we imagine it might appear not less but more emotive?

Apart from the golden ratio, there is another beauty truth we could probably all agree upon: The trend pendulum eventually swings. Does that mean that we're in for a face envisioned by women?

In sharp contrast to the tacit perfectionism of filter/ filler plasticity, Doniella Davy, the makeup artist for HBO's aesthetic bombshell Euphoria, said in an interview with Allure that she, herself, leaves the house every day in a different color of glitter or eyeliner because she's presenting herself to the world in a way that feels authentic. "I don't need anyone's approval," she put it. Similarly, rather than using makeup to convey a character's stereotypical core identity in keeping with traditional Hollywood sets, Davy applies a Technicolor palette to the show's stars as a way to signal their changing and changeable emotional states. It's a vibe makeup artists like Pat McGrath, who rhinestoned eyebrows and gilded undereyes for Marc Jacobs' Spring 2020 New York Fashion Week show — not to mention drag queens and the LGBTQIA communities — have been experimenting with since the dawn of time. Lady Gaga and Lizzo clearly got the memo. But the crayon box sensibility does seem to hold a new grip on our collective cultural imagination. According to Google Trends, the search term "glitter eye" spiked in September in the wake of NYFW Spring 2020, then again in February on the night of the Oscars, when Janelle Monae showed up in a hooded dress dripping with thousands of crystals — part Little Red Riding Hood, part disco ball — matched by glittery silver eyeliner and cherry red lips.

One potentially telling facet of these new trends' appeal is the fact that they leave much more room for experimentation and customization. Because if beauty is based not just on symmetry but also on value and rarity, and if a glut of influencers have all bought the same injectable features and nearly anyone can go out and mimic them by following one of thousands of rote YouTube tutorials with a highlighter stick and some concealer, does that face even look special anymore? What, then, will we all be fixating on in the decade ahead? Look a little closer at Euphoria. There is a common denominator: Across moods and characters, the skin beneath operates like a clean canvas. It looks raw, fresh, tween. And its desirability isn't limited to the show, to 20-somethings or to Hollywood. It's already attracted a cultish, worldwide following.

The Korean beauty world calls it "glass skin." The basic properties are pristine porelessness and crystalline clarity. We can supposedly achieve glass skin by slathering ourselves daily with several kinds of moisturizers, toners, hydrophilics and exfoliants following a bajillion-step K-beauty routine. Or, in certain states where it is legal, we could have semi-permanent BB Glow pigment microneedled into our skin. But one downside to tattooing fake skin into actual skin is that BB Glow needling is not FDA approved and runs the risk of severe allergic reaction, among other untested, uncharted waters. Artificial intelligence could help. As though to underscore our oncoming skin-tone mania, at CES, the tech expo in Las Vegas this January, the two main beauty attractions were Procter & Gamble's Opté wand and L'Oréal's Perso, both AI gadgets that purport to scan and analyze skin in order to optimize the camouflaging of spots, sunspots and hyperpigmentation over time.

Plastic surgeons, whose procedures, injections and treatments have proffered permanent (or semi-permanent) versions of the contouring and highlighting that ruled the 2010s, are also thinking about how this pendulum shift could affect their practices. "When times are harder and people have to work harder, more chiseled, masculine features become more desirable. Because of this, in the last decade, you saw a lot of chiseled features come into play," Dr. Simon Ourian, a cosmetic dermatologist, tells me, in the glitzy waiting room of his Rodeo Drive enclave, Epione, an aesthetic surgery center in Beverly Hills. Referring to the economic challenges of the Great Recession and its recovery over the last decade, he goes on to say, "Women who were trying to show their strength and independence came to fruition by showing very strong features." But, he adds, for centuries, when the economy is strong, as it seems to be now, society has appreciated a softer, "more feminine look."

As of 2018, 85% percent of board-certified plastic surgeons in the US were male, while 92% of their patients were female

Ourian invented the Coolaser, a cosmetic dermatology office mainstay that evens skin tone. He is also the A-list's go-to expert in Hollywood, counting among his openly vocal celebrity clients Miley Cyrus, Iggy Azalea, Lady Gaga and the entire Jenner-Kardashian clan, including Kylie and Kim.

We talk about what, specifically, that new softer look might be led by, now that the chiseled cheekbones, chins and jawlines Ourian pioneered have become a worldwide phenomenon. Given his inside line, I'm hoping he'll share what the starlet subset is starting to request that they weren't requesting a year ago. He defers, not wanting to dictate trends from his "little office in Beverly Hills," but he admits he derives all of his trend intel from Facebook and Instagram, casually mentioning, on the subject of the platforms' instantaneity, the summer boob job. "Temporary breast augmentation started a few years ago because now we can inject fillers into the breasts and they go away after a few months," he explains. "So if you don't want to commit the rest of your life to being one or two sizes bigger, you can try it for a summer and fit better into your bathing suit." (And, judging by the rash of articles about the surge of temporary, non-invasive "Botox brow lifts" among the same cohort of stars and influencers who personify "Instagram Face," it's not just lips and breasts that are getting these temporary enhancements.)

And does this mean a person could theoretically "try on" Ourian's signature cheekbones too? Will party prep soon include the prosthetic cheekbones that paraded down Balenciaga's controversial Spring 2020 runway? According to Ourian, yes. "You can do the same thing with your face," he says. "You can get a filler in your face that lasts a month or two and if you don't like it, it goes away ... It's like trying something on in a dressing room. That appeals to the concept of the Instagram generation who want to change a filter and see how they look."

Whatever strange, weird extremes the fashion world might pursue, however, Ourian maintains that neither of those two adjectives should be confused with beauty. "One definition of beauty has been average," he notes. "You take a thousand people in a society and you superimpose that face. The average of those faces is what's considered to be beautiful by the people of that society, because they are not very strange." But one thing, he admits, has changed: "Now that instead of seeing a thousand people, our eyes are used to seeing millions of people because of the internet, our average has expanded."

"When times are harder and people have to work harder, more chiseled, masculine features become more desirable. Because of this, in the last decade, you saw a lot of chiseled features come into play." —Dr. Simon Ourian

In keeping with our ocular intake's exponential widening, Ourian concedes that the spectrum for what could be considered beautiful has expanded. Noses, he says, are no longer really a thing. "Ten years ago if you showed someone with a larger behind or a larger nose or a different skin color, few people would jump at it and say that's beautiful," he says, citing the model Winnie Harlow, who's rendered the skin condition vitiligo no less a beauty disqualifier than blue eyes or blond hair. But symmetry, he emphasizes sternly, will never go away. Rather than a cathedral, he points to the sleek sofa I'm sitting on and says pointedly, "Even furniture looks better when it's symmetrical."

After a decade of the Ourian-Kardashian beauty dynasty, however, LA's young, rising beauty vanguard seem to be ready for a look that's less kittenish, more renegade. When I meet up with 26-year-old photographer Kelia Anne MacCluskey, who's shot for PAPER, Playboy and The New York Times, and her boyfriend Lucky Pettersen, 27, a casting director who's cast campaigns for Gucci, Levi's and Calvin Klein, for drinks at a tapas spot in Highland Park, both suggest in their own way that they're constantly searching for models and talent with gap teeth or a unibrow, the sort of authentic, identifying mark that makes an instant, unforgettable impact. Pettersen, for example, philosophizes on Gen Z's desire for honesty as exemplified by 22-year-old model Salem Mitchell. After trolls compared her freckled skin to overripe fruit, Mitchell launched herself on Instagram by posting a photo in response, hashtag #bananaface.

"One definition of beauty has been average. You take a thousand people in a society and you superimpose that face. The average of those faces is what's considered to be beautiful by the people of that society." —Dr. Simon Ourian

Yet as empowering as a swing toward this aesthetic individualism might sound, it would be naïve to assume that any new trend would outright eschew the inherent pressures of the beauty paradigm. New standards will be set, new expensive treatments spawned. At the moment, unibrows and sequin brows aside, all overarching signs point to a standard centered on pristine skin.

In Perfect Me, a book about the perils of our current global beauty ethic, British academic Heather Widdows attributes this growing preoccupation to a "forensic gaze" fueled by visual culture and the omnipresence of hi-def screens and cameras that require us to look smooth and luminous "not just when our picture is likely to be taken (on holidays or at weddings), but increasingly all the time ... given that we can imagine ourselves (or our failings) being photographed in almost any context." In an interview with PAPER, she cautions that the "forensic gaze of HD TV and selfie culture is something we need to take much more seriously as shaping who we think we are and putting pressure on us to perfect our faces in ways that really aren't possible for living, breathing, sweating, aging human beings." She also argues that the widening of the beauty spectrum under the auspices of the internet might actually be just the opposite: a contraction. Whereas, pre-internet, beauty norms were decided by the more localized scopes of one's cultural community into micro-ranges, these ranges are converging into a more singular worldwide beauty window with less room for divergence: "thin and slim, with breasts and butt curves, smooth, luminous, glowing skin, and large eyes and lips ... White women are just as unable to attain the beauty ideal without intervention as Asian and Black women are," she says.

But what if we could regrow our own genuine genetic skin the way it looked before sun damage, cigarettes, sleeplessness, acne and other little scars set in?

What if we rolled out of bed in the morning and didn't have to waste a single second thinking about makeup, let alone fueling the industrial beauty complex and its ecological fallout with our hard-earned third-wave feminist salaries because we'd woken up in our own living, breathing, sweating childhood skin? "That is truly the holy grail of cosmetic dermatology," according to Ourian. "What makes a kid's skin perfect aside from the fact that they haven't been exposed to the environment — their skin repairs itself much faster," he explains. Up until now, there was no way to unlock the skin's reparative memory. Ourian gets enthused again. Declaratively, he pronounces: "Stem cells are going to be the biggest thing." And he's not talking about the Vampire Facial craze. He does not think having one's skin needle-scratched raw and bloody before pouring stem cell serum derived from placentas onto it is of any use. No, if you ask Ourian, the holy grail, the next Botox, is injectable skin.

"White women are just as unable to attain the beauty ideal without intervention as Asian and Black women are." —Heather Widdows

In his office, he already performs a version of it with stem cells derived from the patient, but it's expensive and not as efficient or effective as Ourian believes it will soon become. "First I have to get rid of all the old junk, Coolaser to get rid of the sun damage," he explains. "To get this baby skin we have to retrain it to keep itself healthy, and that's where the stem cells come in ... but in the next five or ten years we will achieve a level of age reversal that will mimic the way your skin was in your 20s or pre-teens." He's hoping it becomes as mainstream as Botox: "For a few hundred dollars, you can get it done."

Then and now, there will always be the non-conformists who consciously push back against the ever-tightening beauty construct, whether it's dictated by Kim-face, Glass-face or any face in between. The artists, activists, intellectuals and outsiders: Alicia Keys, Salem Mitchell, Frances McDormand, Heather Widdows, maybe your daughter or son or nonbinary child, maybe mine. For her part, Widdows has this advice for anyone who wants to help broaden beauty norms: "Call out 'lookism.' We need to name it (as we once named sexism) and make body shaming not and never okay." In the meantime, Simon Ourian will be chasing his white whale. As we age, the extraorbital fat pads that cushion our eyeballs in our ocular sockets erode, and the eyes sink into the face. "We can put a fat pad in the back of the eyes surgically, but not in a quick procedure," he explains. "So that keeps me up at night. How do I put fat pads back behind the eyes without cutting faces?"