Break the Internet ®

Cursed Images: Finding Comfort in Discomfort

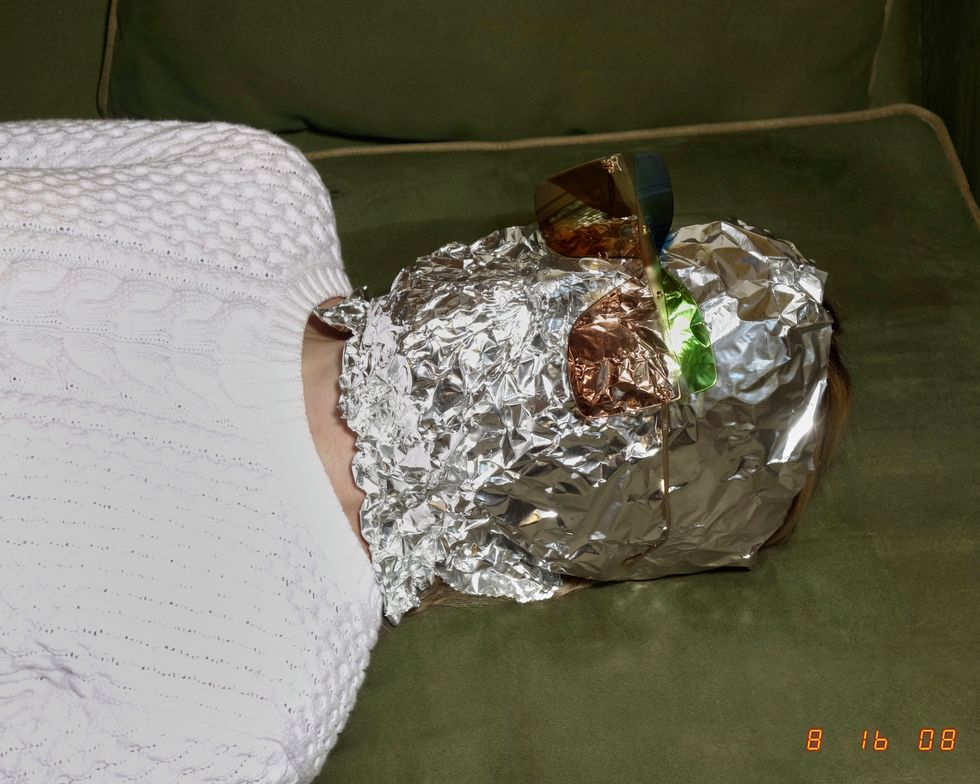

Story by Matt Moen / Photography by Corey Olsen

09 December 2019

A dress shoe filled with baked beans — cursed. A beady-eyed knock-off Teletubby posing next to a crying child — cursed. A carpeted staircase lined with Furbies — cursed. It's a sensation we all know when we see it — a friend eating mayonnaise straight out of the jar, a porcelain doll tucked in the back corner of your grandmother's closet, a dumpster full of fresh broccoli discovered behind a concert hall at 2 AM — yet nevertheless struggle to put into words. They lurk in the corners of our feeds, the runoff from our group chats, the bottom of Google searches we instantly regret making; the cursed image is the mold collecting along the edges of the internet. We have no idea where they come from, we know they shouldn't exist and yet there is something about these so-called "cursed images" that fascinates us nonetheless.

The cursed image as a concept originated from a Tumblr blog in 2015. "At the time, I had a voyeuristic hobby of searching the archives of Flickr to look at forgotten flash photography from years in the past," explains the owner of cursedimages.tumblr.com, a 19-year-old female photography and film student from the American Northwest who spoke on the condition of anonymity. "Some of these forgotten photographs just had an eerie mood about them, like someone had captured a moment from a dream or another life. I was particularly interested in finding photos of dark and empty rooms, mannequins and costumes, all of which became common themes among cursed images."

The very first image ever posted to cursedimages.tumblr.com was that of an old farmer surrounded by crates of red tomatoes in a wood-paneled basement, expressionlessly staring at the camera. "It's the perfect cursed image to me because there's nothing inherently unsettling about any part of it," she says. "It's a totally mundane moment transformed into something else by the camera and the new context I've given it." The image gives off the feeling that you've accidentally walked in on some strange produce-based ritual and witnessed something that you were not supposed to. The effect is visceral: A cocktail of dread, unease, disgust and confusion washes over you. "They're images of memories that never actually happened to you, but the moment you see them, it's suddenly happening to you."

Sunglasses: Fendi

The initial image only gained a little more than a thousand notes, which is hardly viral by today's standards, but the concept of the cursed image took off, with scores of copycat blogs popping up across Tumblr, then migrating to Twitter, Reddit, Instagram and, if you were particularly desperate, Facebook.

Now, four years later, a community of cursed curators flourishes on Instagram, each with their own specific tastes and definitions of what it means to be "cursed." Some accounts choose to tailor their content to specific sub-genres like the dysfunctional furniture of @uglydesign or the ever-popular well of odd food combinations like the nauseating amounts of hot dogs and baked beans found on @boyswhocancook. "If it needs a caption underneath to explain what makes it funny, then it isn't funny," says Instagram user @earlboykins4, whose own preferred flavor of cursed content involves visual gags like a man holding a medieval sword as a small chihuahua pokes its head out from his shirt or an alligator wearing green sunglasses and a tiny yellow sweater traipsing along the beach.

"People have always been obsessed with the oddities of the world dating back to freak shows and other circus stuff, moving into tabloids and crime drama," explains Jim Swill, owner of the Instagram account @Noided. "We love that tolerable forbidden zone, not too disgusting to turn around, but weird enough to keep us looking."

"Memes spread well when they resonate," says Ryan Milner, an assistant professor in communications at the College of Charleston and author of a book about the rise of meme culture, The World Made Meme. Milner points out that most of the time, memes resonate because they're either funny or sentimental. But in the case of cursed images, they "resonate because they're creepy, because they're scary." Ultimately, whether we're creeped out, afraid, amused or touched, all of these kinds of memes provoke "different emotions that make us feel something. And we share what makes us feel something," he adds.

Related | Break the Internet: BTS

The cursed image as a meme can trace its roots back to Creepypasta. For the uninitiated, and ignorantly blessed, Creepypastas were essentially a mix of scary stories and urban legends that cropped up on various forums and dark corners of the web in the late 2000s and early 2010s. A subset of copypasta, which were basically stories that were copied and pasted that circulated online like chain letters, Creepypasta notably gave rise to characters like the infamous Slender Man, Jeff the Killer and, most recently, the moral panic-inducing bird/woman chimera, Momo. "The thing around Creepypasta stuff is that sometimes it blurs the lines between genuinely, earnestly supposed to be scary and something that's scary but also playful and funny," Milner explains. "You can get that with cursed images as well, that balance between stuff that's supposed to be scary, that's supposed to make you raise your eyebrows, stuff that is striking and funny in a really kind of morbid way." In this way, Creepypasta functions as a proto-meme for cursed images, laying down a roadmap for how to unsettle the digital masses.

According to Joshua Citarella, an adjunct professor at the School of Visual Arts who specializes in post-internet art, horror is a vital part of the online experience. "Despite its many wonderful features and side attractions, the internet is first and foremost a place for horror. We come to be horrified." This was perhaps most true in the wild, unmoderated early days of the Internet, where paranoia over predators lurking in teen chat rooms ran high and a few wrong clicks could easily trigger a jump scare on an unvetted site. In her own deep dive on cursed images, The New Yorker's Jia Tolentino recalls that "in the '90s, the shock site Rotten.com became famous for publishing a fake photo that purported to show Princess Diana's corpse just after her death in a car crash." At the time, the internet felt like a vast and mysterious place with bogeymen around every corner — but that's also what made the whole ordeal kind of thrilling.

What separates cursed images from shock sites that depict outright gore and peddle cheap jump scares (like 4chan's infamous /b/ board or the r/FiftyFifty subreddit) is that the terror is implied rather than stated outright. There is an imagined narrative behind it, albeit frequently opaque in meaning. You're left with the sense that there was a series of horrible and bizarre events that led up to the creation of a cursed image. Stripped of context and lacking any rational explanation, a dark aura often hovers around these images, and the uncanny valley opens up like the Grand Canyon, forcing us to confront the break in the simulation before us.

"We are drawn to 'cursed images' because they somehow present us with a nagging ambiguity," says Francis McAndrew, a professor of psychology at Knox College. "Things that we cannot quickly make sense of trouble us and hold our attention, and we feel compelled to analyze them until we feel as if we understand them."

"To talk of the curse[d], we must mention Sigmund Freud, who, at the turn of the 20th century, attempted to describe its effect with his theory of the uncanny, which he identifies as a strangeness in the ordinary, that he traces to unusual repetition, mechanical entities that appear human or prosthesis that invoke a sense of unease," says artist Ed Fornieles, who recently curated a group show on the topic of cursed images. "However, we need the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan to supply us with a broader definition. Lacan writes that the cursed places us 'in the field where we do not know how to distinguish bad and good, pleasure from displeasure.' This accurately describes the limbo the cursed leaves us in. Unable to reconcile what is in front of us, we hover."

Related | Break the Internet: Pete Davidson

Going a step further, the Bulgarian-French philosopher Julia Kristeva, a disciple of Freud and Lacan, posits in her theory of abjection that subjective horror is the result of a breakdown of the Self and the Other, i.e., the sensation of seeing your finger bleed and understanding that the blood pouring out is simultaneously a part of your body and not. It is in these instances that we are confronted with our own mortality, and in order to keep it from crushing us, we dismiss the feeling as abject, disgusting or horrifying as a way to defend ourselves. In this regard, horror and disgust operate as two sides of the same coin, with horror being the logical revulsion to something that threatens us and disgust being an emotional response to something distasteful or unpleasant. Unable to parse whether a cursed image poses a threat to us, our fight-or-flight response stutters and leaves us trapped between the two, recoiling but transfixed. Not scary in the traditional sense of inducing mortal terror, the cursed image poses more of an existential threat to our sense of self, challenging our sanity with its various flavors of creepy, eerie and uncanny scenarios.

In a chaotic world that seems to defy logic more and more with each passing day, the cursed image offers us a perverse sense of comfort by reaffirming the fact that it's not just us who seem to be going crazy. The cursed image exists as a direct challenge to an Internet flooded with deepfakes and photoshopped candids, positing a reality that is far stranger than anything we could fabricate by ourselves. The cursed image feels like proof that we've crossed over into an alternate dimension, a Twilight Zone populated by the mundane. The cursed image haunts us and, scarier still, we like it.

Photography: Corey Olsen

Prop Stylist: Megan Kiantos

Prop Assistant: Dominique Turek