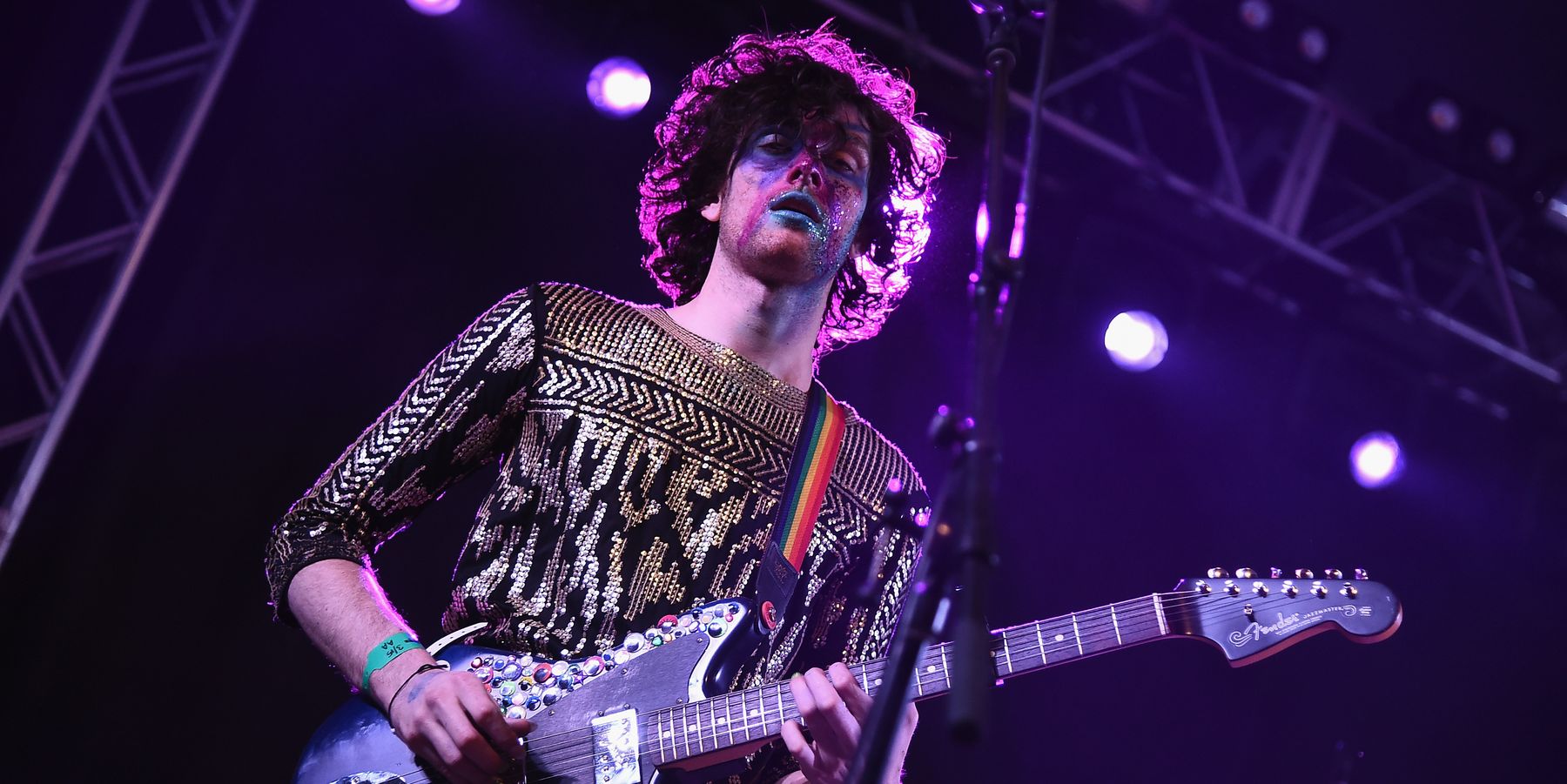

As sexual harassment allegations involving hugely popular entertainers, from comedian Louis C.K. to Bill Cosby to indie music darlings, queer band PWR BTTM, emerge increasingly frequently, we have an obligation to ask ourselves why. Some have alleged that abuse often occurs in artistic communities because of sheer white maleness. But Baltimore writers and artists Maura Callahan and Rebekah Kirkman say that it's bigger than toxic masculinity — it's our whole society.

In their national attention-grabbing piece for City Paper, "Abuse and Accountability in the Art Scene: A Reckoning," Callahan and Kirkman explore a series of situations in which abuse and harassment were carried out in the Baltimore arts community. They speak to survivors of assault and abuse, making sure to center their stories and feelings. Callahan and Kirkman also talk to experts and offer up difficult solutions to the ongoing epidemic of sexual violence. PAPER sought the duo out to hear their story and the changes they hope to see in their community.

What was the impetus for the piece, why write this now? Did it feel as if abuse within the Baltimore arts community was hitting a critical mass? Or a particularly egregious act occur?

Kirkman: I think it's most accurate to say that it felt as if abuse within the arts scene here was hitting a critical mass, yeah. We had been hearing about abuse in different ways—social media callouts but also people just telling us directly what someone had done to them, things like that. It got to a point where we felt like we had enough beginning knowledge about instances of abuse. We were tired of this being a conversation that many people within this art scene will have but then they decide they're not sure what to do with it and it all gets swept under the rug, brought up again later, then swept away again, and so on. The conversations, and the issue of abuse in general, of course, aren't new at all but the ways we all talk about them, and how we are starting to demand better treatment and accountability—those things feel newer or evolving, at least. Another thing that really lit a fire under us on this story was that the paper we work for—the Baltimore City Paper, the city's only alt-weekly newspaper—is getting shut down before the end of the year. So we wanted to try and start to untangle some of these knots in this issue, in this scene that we are so entrenched in as viewers and participants and peers. We wanted to try to let survivors and activists and allies speak on it, we wanted to write it down and draw connections and examine nuances and see how maybe the scene could start to do better by survivors of abuse.

Callahan: There were a few cases where multiple people would come forward online with their experiences about the same abuser, someone who holds a lot of power in the art scene here—in those cases the survivors wouldn't speak to us on the record out of fear for their own safety and privacy, which is understandable. But it wasn't one incident or one abuser, no. That story might've been easier to write, if it was about one guy with a record, but this was a story about harm suffered at the hands of many people, who often cannot be criminally charged because what they're doing—emotional abuse, for example—isn't necessary illegal, and even difficult to name in some cases. This is something that we'd been chewing on for ages, not knowing how to write about it, and like Rebekah says, it got to the point where it was now or never.

What was the goal of the piece? To educate? To explain? To offer a fix? None of those? All of those?

Kirkman: All of those, in some ways. To me it felt like an earnest attempt to give a platform to people who are already having these conversations—survivors of abuse and assault, their friends, allies, and so on. There were also certain things we tried to sort of clarify for readers or people who maybe don't steep in this topic all of the time, like hey, by the way, emotional abuse is very real and often devastating—that is something more people need to be aware of. For me this stuff hits close to home too. I kept thinking about people I love who've been through truly horrible shit and how most of the time there was no accountability at all. Literally nothing. They have had to heal on their own and try to feel safe again. They are still healing.

Callahan: Right—everyone has either been abused, been an abuser, or cared about someone who has had one or both of those experiences. So this is an important issue for everyone, and the possibilities for how to deal with it need to be more accessible. Bottom line, we just wanted to put it out there, in print, to use our privileged position as people with bylines to amplify what people in the community have been saying for decades. We wanted to agitate in a way that any story about horrific events should, but to do so in a way that's nuanced, neither opening a wound or trying to cover it up.

It feels like you both did extremely thorough work not only documenting specific incidences but also offering solutions and rehabilitative options. That's ambitious for a single piece of work. How long did this piece take to write?

Callahan: It feels like it's been years in the making, just having these issues in front of us and not knowing how to deal with it as writers for an alternative publication. But when we started to get a real sense that our paper was doomed, we sat down with our editor and decided it was time to finally put this out. It wasn't until we were really in the thick of it, though, after we had spent months doing research and talking to survivors and organizers and artists, that we could begin to understand how we could construct this in an empathetic and useful way. In a sense, we felt like we had to throw out what we knew about reporting and start from somewhere else. When we started, we had recently binge-watched "The Keepers" on Netflix, about the overwhelming conspiracy to silence victims of abuse at the hand of priests in Baltimore Catholic schools and its connection to the murder of a nun in 1969—a cold case that was initially investigated by the City Paper, by the way—and we were struck by how the filmmakers centered the survivors and presented the horror of the abuse on their terms. When we talk about abuse, especially the abuse of women, our tendency is to distance ourselves and say, OK, but what are the facts? Is any of this real? Needless to say the facts are important, but I think too often, especially in reporting, we neglect to recognize how survivors of abuse feel as vital elements of the story. The way someone is devastated, that's real, and for us as women who are personally embedded in this scene, that felt increasingly tangible. So we started from that feeling.

Kirkman: Yeah, that we are embedded in this scene was pretty huge, and I mean I guess that's often the case at City Paper; we both went to art school in Baltimore and so we often have friends and peers in the scenes that we're covering—but that was a thing to problem-solve for sure. We are also both art critics (Maura is CP's performing arts editor and I am the visual arts editor) so to me this piece is also a critique of the scene. You know, like, it's really frustrating to see fliers for shows featuring someone we know is horrible and we know that people just let that dude get away with it. So maybe this was a way to confront that tendency.

You choose to center the survivors of these assaults, but why not the aggressors?

Kirkman: Society as a whole centers aggressors and dismisses survivors of abuse. There have been big moves on the part of feminist and queer activists in particular to center survivors and their perspectives, but that's still definitely a work in progress. I think and hope this piece can help sway readers toward a more survivor-centric framework if they're not already there. I think that there definitely needs to be people doing work with aggressors in order to hold them accountable, so like, research about why people choose to abuse their partners, why people cape for abusers rather than standing up against abuse, what sorts of accountability processes are effective, and things like that are all super important. But at the end of the day if we aren't first showing up for survivors, validating them, listening to them, finding out what they need in this process then we've got the wrong focus, we're kinda just doing what's always been done.

Callahan: Yeah, the default for so long—for the criminal justice system, for media, for everyone, really—has been to not believe women, to not believe survivors. That method doesn't seem to be working out so well, except for abusers, and their time is coming to an end, even if we do have one as president. When it comes to dealing with this journalistically, I feel that too often, by focusing more heavily on the abuser and the act of abuse itself as opposed to the survivor and what they're dealing with during and in the wake of the abuse, the problem becomes sensationalized without really being addressed. So as a woman, as a writer, I'm tired of seeing that. We wanted to come from the other direction.

We're seeing a lot of issues of sexual assault and harassment popping up in other arts communities — comedy, as well as indie music — you think you're looking at an issue that runs deep everywhere? Are these problems unique to their communities or can they all be reduced to patriarchal rape culture that privileges toxic masculinity? What I mean is, is there a through line?

Callahan: Absolutely. It's not just about toxic masculinity; it's about our culture privileging domination. Patriarchy and white supremacy play an inextricable role, of course, because those are the dominant cultures, but it boils down to one person or group of people gaining power over another and fighting to maintain that power. That's the through line. It exists everywhere—we've seen it in queer communities, too, like if you look at the PWR BTTM mess. The problem will often manifest uniquely in certain communities and those communities will respond, or not respond, in their own way, and those variations are worth getting to understand. Maybe that's where we start in actually fighting this thing, in our own communities, however small or insulated.

Kirkman: Yeah, it's just pervasive and like Maura said abuse is really about control and domination—it feels important to stress that it's not just men abusing women, that every person of every gender is capable of causing harm. We do spend a long section in this piece we wrote dissecting the "masculinist bohemian," as artist Catherine Pancake refers to the type of dude who runs the scene and gets away with abusing people, but that type of man is someone we know a lot about from paying attention to the scene here, from talking to survivors and friends and others. So listening to survivors and centering them is crucial. That's the baseline. And it does seem like fighting this issue locally first is the way to go. I mean for the purposes of this story we focused on this pocket of the local arts scene, primarily the DIY scene, but this issue exists everywhere and even in the most radical spaces, and for certain demographics the prevalence of abuse is much higher.

I really really appreciate you two doing the work of talking to empathetic experts who have real solutions to some of these issues. None of the options you present are band-aids or easy fixes, you're agitating for real cultural shifts and restorative justice. That's hard work. Can you talk about why it was important to include this section, even though fixing emotional rifts in society can feel murky and solutions aren't easy?

Kirkman: That's true, none of these changes or solutions are simple, and every abusive situation is unique and every survivor's needs are unique. It was very difficult to sort through and articulate what we learned from reading up on accountability and restorative justice and to talk with these "empathetic experts," as you called them, and pull out examples or general threads of things that might work and lay them out in this piece but not be overly didactic or authoritative, to honor the complexity. It was also awesome to read all of these books (see the resources section at the very end of the piece) and zines and to talk to all these people who, it seemed, were more or less on the same page that whatever the solution is, one of the guiding principles needs to be compassion. That was something we talked about quite a bit, I think, because it is really easy to think that just cutting out the problem—isolating or shunning the abuser, for example—will fix it. And that's just what prisons do and prisons are not in the business of rehabilitating people. So that section, and acknowledging the murkiness, felt very necessary. It's also one of few things that, for me, gave me hope while working on this piece. I definitely got swallowed up over the course of the many months that we worked on it, just feeling like everyone is horrible and selfish and nothing will ever change. But maybe it's just that not enough people know about this stuff, or maybe not enough people take their place in their communities seriously, so here are a ton of great pieces of information to get your mind turning on it.

Callahan: Working on the story taught me that yeah, the way we respond to abuse is frustratingly complicated and there's no clear answer, but how we start answering those questions is actually pretty simple: Believe survivors, and focus on their needs rather than retribution against the abuser—compassion over punishment, as Rebekah says. And maybe before we can even get to that place, we have to unlearn all the victim-blaming, all the internalized misogyny and, for women especially, that unruly self-doubt. It's totally on the abuser to make amends, but as we've seen they won't even try a lot of the time, so there are things survivors and allies can do to move forward, things that may be so particular to their situation and community that there really isn't a clear guide.

I'd love to just know what you both are feeling in the days after this piece has been published. Did you get any responses you'd like to talk about? Does it feel like a relief to have this all out in the open and sharing the specific issues of your community on a national and international scale?

Callahan: Speaking for myself, this may have been the biggest cathartic release of my life. We'd both been working on it for so long and had been dealing with our own personal crises in the meantime, including the impending demise of our publication, which we love dearly. In our capacities as writers, this was probably our last big push to cement the importance of the City Paper, because it's really the only place where this kind of story could've been published in Baltimore. In the past when we've criticized elements of the art scene here, there's been some pushback, but this story seemed to really resonate. In the Baltimore scene, everything we wrote about has existed in murmurs—online and between individuals and in small organized actions—but it had yet to really receive the validation of appearing in a newspaper. It's funny; because we work for a local paper, we did not anticipate this story to make the rounds nationally or internationally, so we wrote it with our immediate community in mind as our audience. So the fact that it is circulating and resonating more widely is insane—we've never felt like we've had that reach before, and it took looking very inwardly to do it.

Kirkman: Yeah that took me by surprise, how far it has reached. Kimya Dawson retweeted it! That it resonates with so many people in a way really hurts because I'm thinking again about so much pain and abuse and violence and trauma people are burdened with. I'm thinking again about people I love who have been through utter hell. I am glad to see people all over the place engaging with the piece though and I really hope that people find it useful. Beyond validating someone's experience, which is crucial, I hope that maybe even in a small way this piece can drive people to actually recognize their roles within their communities and how they can be helpful and how they can support each other and take care of each other. It is terrifying to feel alone in the world and, personally, I'm grateful for every person or book or story or piece of art I've encountered that has made me feel less so.

Read the duo's full City Paper piece here.

Image via Getty

From Your Site Articles