Care

What It's Like Being Under Lockdown in Spain

Photography and words by Carmen Daneshmandi

16 April 2020

Far before there was a pandemic, there was already loss. The year 2020 was barely four months in but had distressed my family, particularly our family living in Iran. January brought looming threats of a third world war and a commercial plane was shot down from the sky over Imam Khomeini International Airport only a few days before I had planned to arrive in Tehran for a personal project. I cancelled that trip but, two weeks later, my last living grandparent passed away in Tehran and, because it was unsafe to go there for a funeral, I was instead FaceTimed into a makeshift memorial.

Along with Iran, my family is spread across Washington state (where I grew up) and the south of Spain, so geo-politics and regional tension had always implemented a crippling form of social distancing well before we were washing our hands for 20 seconds and staying at home. But, once coronavirus started making headlines about its severe impact — particularly on those same three places so central to my family and me — this evolved sense of distance and separation anxiety seemed a thing of this new continuum I had to accept.

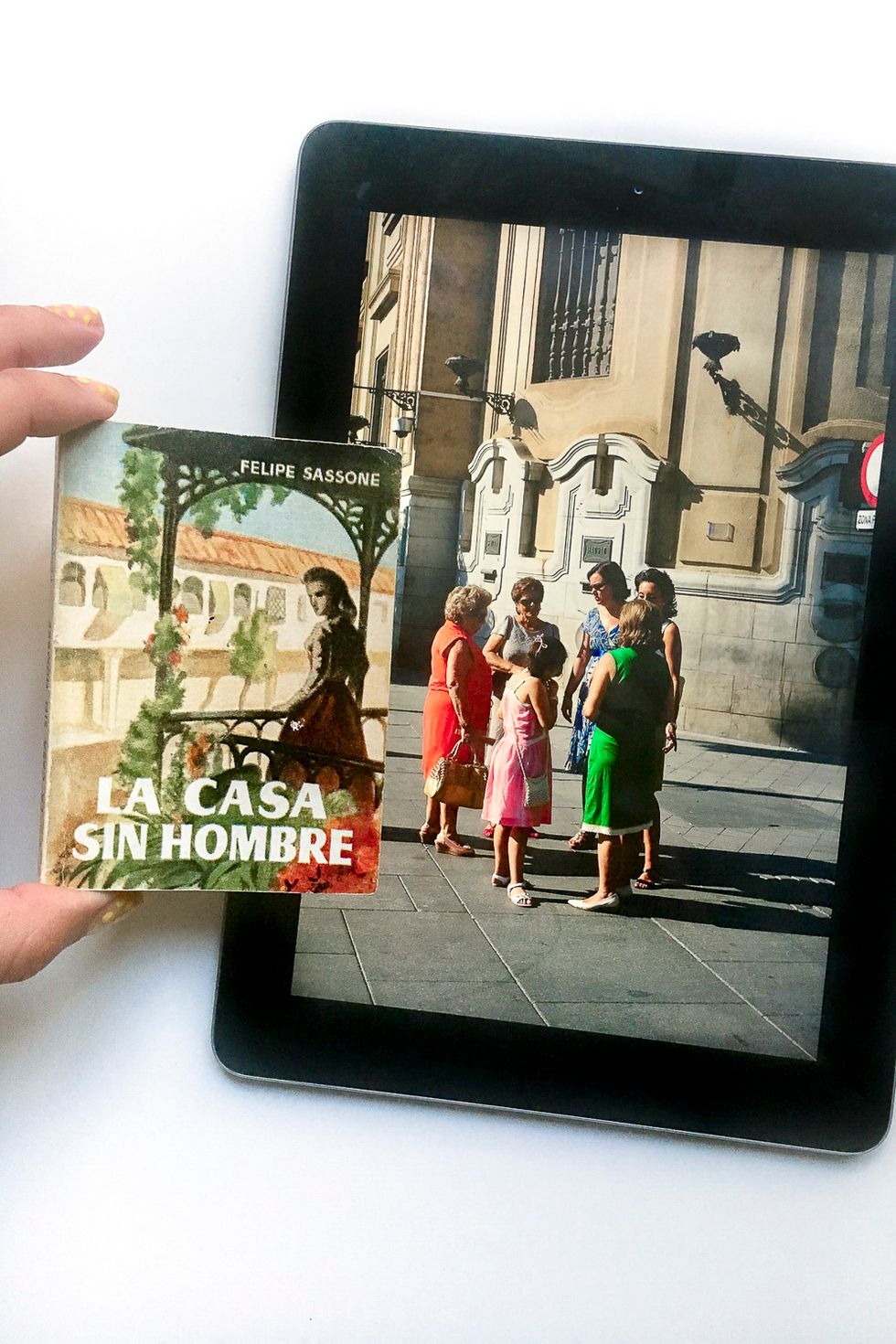

By the time many countries and cities around the world instructed their citizens to stay home, further amplifying the sense of disorientation and dislocation that many of us have been experiencing since the pandemic began, I had already been feeling disconnected from any sense of home and family for some time. I had moved to Zaragoza, Spain in December of 2018 when my younger sister Karimeh got placed into a teaching program in the city. After living in NYC for a few years, I had wanted to move to Europe to explore new opportunities and reconnect with my Spanish side. Neither my sister nor I had ever been to Zaragoza and, for over a year, I had trouble feeling a bond to the reserved demeanor of the people or city for that matter. The Spain I grew up knowing was that of my mother's Sevilla with our family down south, which matched many of the better traits of the US south in hospitality, loudness and passion. Here in Zaragoza, I didn't see myself reflected in the energy, the people or spaces I interacted with every day. There weren't many real job opportunities as a photographer here for me and so I would often escape my reality and go to New York for the work (and friends and general feelings of happiness).

When the official lockdown began here, I didn't initially set out to document my experience; the idea that social isolation could become a creative project wasn't a priority. It wasn't until I experienced a sudden, heart-felt response to simply seeing and talking to neighbors I had never met before that this work started taking shape. The community I had longed for was finally showing its many faces and it gave new charge to my creative air and day to day. It turns out, there was a silver lining to being forced to remain in a place I had otherwise no sustainable relationship with before. The community around me was actually showing signs of life here on my street, Calle La Paz.

At the same time as I was getting to know my neighbors, there came news of ice skating rinks being turned into morgues in Madrid and rising daily mortality rates suggested an atmosphere throughout the rest of the country straight out of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. A public that had always greeted each other with two kisses now looked at one another at the grocery store with a sense of suspicion. And so while there was this new perspective of pause and possibility on our street, there was also a larger sense of guilt. It felt irresponsible and strange to be connected to three of COVID-19's most affected countries but to be doing relatively okay here in our apartment. There was a cognitive dissonance to reading about rising death tolls in other parts of Spain, testing and medical delays in the States or obfuscation and sanctions-related impediments in Iran while my sister and I strung lights between our balconies like this new circumstance was a holiday. I found myself feeling anxious and defeated but also inspired and calm. I guess there is no binary to this experience.

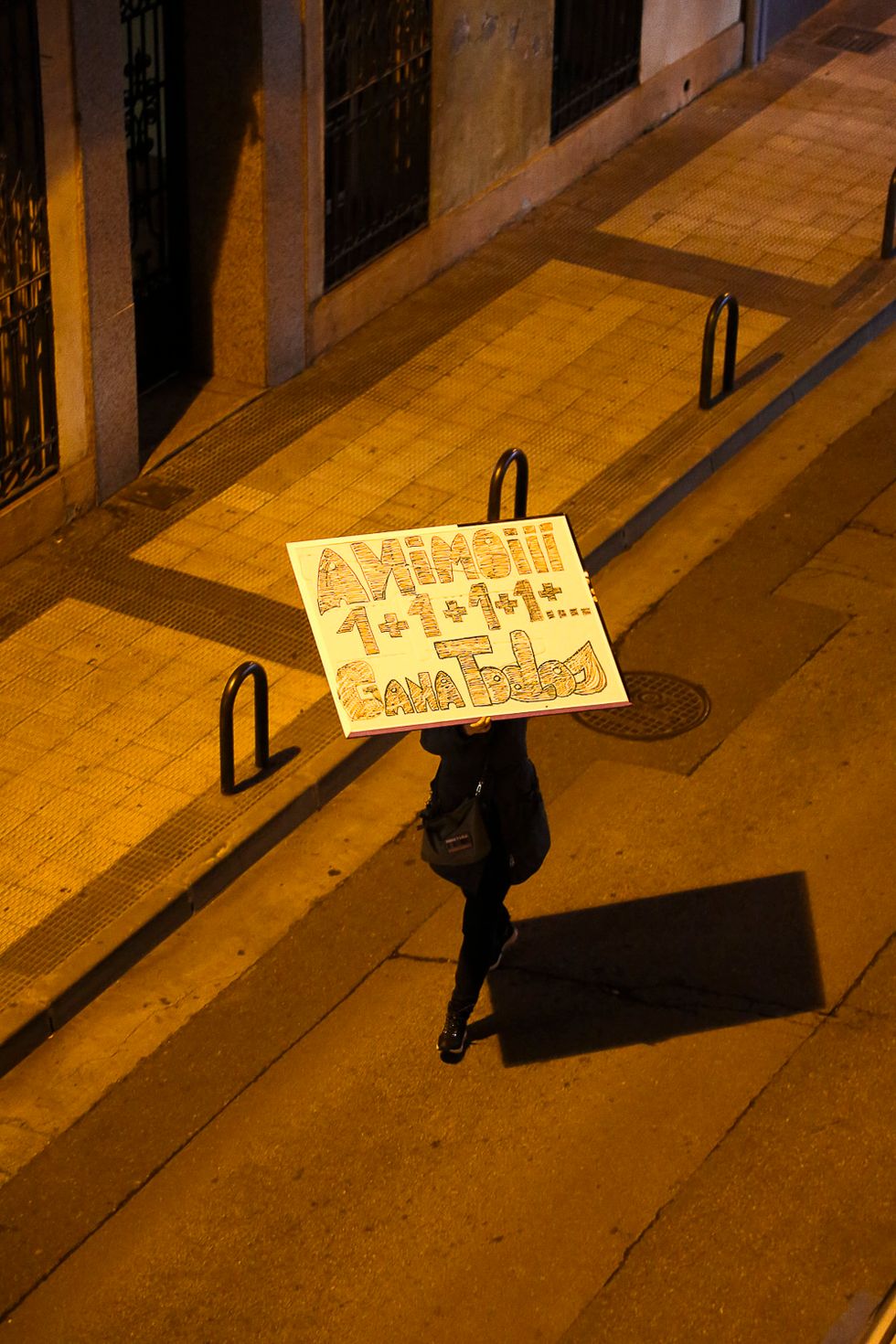

Dating its first image to when the lockdown in Spain began Sunday, March 15th, 2020, this lockdown "diary" taps into a personal spectrum of this experience and chronicles those stark public sightings, the blossoming of (balcony) community, moments of domestic inspiration, and a prolonged celebration of Norooz (Iranian New Year) as a means of keeping the spirit of locked down space lifted and far-away family close.

"Besar Cura Virus."

The morning after we had sat in front of the TV hearing President Sánchez announce Spain's official lockdown, my sister and I decided to take in "one last walk" around the city while we still could. Right as we hit our corner, the one on Calle Héroes del Silencio, aptly named after Zaragoza's hometown rock band, we saw the romantic, optimistic, hot pink tag: "Besar Cura Virus." Kissing cures viruses. This was the first lockdown image I took, no diary in mind. Only a few days ago did I find out the artists behind the tag were my neighbors, a couple named Nacho and Laura. Two weeks prior to lockdown they had gone camping and found most of the forest run down for timber. Hidden behind a stump they found a pink spray can used to mark trees ready to be cut down,and brought it back to the city to write their message on the block.

Photography: Carmen Daneshmandi