Sasha Velour Is in Her Author Era

by Arya RoshanianApr 10, 2023

“I am trying to survive,” Sasha Velour tells me, in front of what looks like a velour curtain. It’s bright and pink, but Velour is wearing black. “I’m making art because that is survival for me.”

Now’s not a great time for Velour, for me, for a lot of us. Our conversation is dampened by an assault of current events. There are over 450 anti-LGBTQ+ bills floating around the United States; a war between Russia and Ukraine persists; millions of Americans are on the brink of losing their federally-funded healthcare; and artificial intelligence looms as an ethical catastrophe. But even when the cacophony of harmful rhetoric is nearly impossible to drown out, Velour refuses to cover their jeweled ears. They listen and respond — with art.

“Collectively, our definition of art may seem inessential in times of survival, but I think it’s all connected.” They’ve given this a lot of thought. “If we see the work of all people as belonging within the realm of art, or the reasoning to make art as a way of belonging — I think that will also reflect how the people who make it are treated.”

Velour’s conceptualization of art and identity is the thread that binds their debut book together. The Big Reveal: An Illustrated Manifesto of Drag, out now, weaves in and out of memoir, queer history, critical theory, visual art and graphic novel — it fits on many shelves. RuPaul’s Drag Race fans will intuit its title as a wink to Velour’s lipsync performance to Whitney Houston’s “So Emotional” at the series’ ninth season finale in 2017, where they released a torrent of red rose petals hiding beneath their wig — you know the one. It was a moment to write home about, and has since inspired academic essays, copycats and ushered Drag Race into a new, lipsync-for-the-crown-adorned era. In hindsight, it also corroborates Velour’s beliefs in art as a mechanism to innovate the norm.

Much like their book, Velour is a total work of art. Their creations are often as beautiful as they are grotesque, with a careful blend of Leigh Bowery’s decadence, the dialectics of Judith Butler and Mikhail Bakhunin’s revolutionary zeal. It’s possible that such an explanation of Velour ingenuity makes them sound too esoteric, too opaque for anyone who isn’t a club kid or graduate student. As the only child of an emeritus professor and the late editor of an academic journal, Velour is a former Fulbright scholar and holds separate degrees in literature and fine art. They’re smart, but not pretentious, mostly. (“I do get a little pretentious on the microphone sometimes,” they clarify.) Velour keeps the book’s tone informal and meets their reader at eye level. “I love a good academic text that plays with language and strings together long sentences, but I knew my book had to be conversational. I had to ask myself: “Does this sound like Alexander Steinberg’s intellectual voice, or is it Sasha Velour speaking to people in a bar?”

Speaking not in a bar, but at their home in Brooklyn, Velour discusses with PAPER their motivations behind The Big Reveal, examines their Slavic heritage within conflict and explains drag as both entertainment and resistance.

I feel like there’s this elephant in the room where I can’t talk about drag or queer artistry without all the anti-drag and anti-trans legislation that’s happening as we speak. How has your view of the book changed within the context of everything that’s going on?

I feel like this book, with the stories and queer history, is more essential than ever. Facts and truth can combat misinformation. What people decide to do with it and whether they decide to listen is, unfortunately, harder to control — but the stories and information are there. I wrote this book because I wanted drag artists to have access to our own context and our own past, to arm ourselves with information and stories about how we belong as part of world culture and what we’ve had to do to stand up for queer and trans people against oppression in the past. I definitely didn’t predict to what extent we’d be facing those dynamics in real time, like right now. Although, seeing the restrictions for transmedical care, for young trans kids, for women and for bodily rights and autonomy, there’s been movement in the last couple of years to restrict freedom across the board. I was already aware of that when starting this book, and it’s gotten so much worse.

What originally inspired you to write this book? You had to have started it well before all the anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric got this bad.

I was most inspired by queer history, which I’ve been slowly piecing together by reading other history books or out-of-print books from writers who talked about drag in really backwards ways yet still had all this information at their fingertips. I wanted to weave all that into something that used our modern language and understandings and spoke to the present moment. I could’ve left my personal story out completely, but I also recognize that that’s the hook for readers. And to be truthful, I have to reveal my own background and how I came to this story, or where my personal tastes lie, and why. Telling my story is part of that history.

When you put it that way, it makes the “big reveal” that much more multifaceted, because you’re opening up about your personal life that, until now, you haven’t disclosed to the public. Was this always the book you set out to write, or did it evolve and broaden as you wrote?

I’ve always had an idea. I knew I wanted to incorporate visual art and to have the personal and the history come together. But I didn’t know how intermixed it would be. At times, it was more structurally divided — there’s the history section and then my personal story. And it was only when writing it all out that I started seeing really strong connections between stories of my own childhood and tensions in the world at large. And I thought, Okay, we’ll put them together. I also had a really, really good editor. She really helped me weave the pieces of the book together when it was in fragments.

A lot of scholarly texts can be convoluted or difficult to make sense of, especially if you’re not an academic. One thing I appreciate is that you present a lot of opaque ideas and theories in an accessible way without being patronizing or oversimplifying key ideas.

I really do see it as an act of translation, explaining to a wider audience important ideas about culture that are happening within academic circles that, like you say, are hard to understand. I’ve always been interested in translation, saying something that’s legible to a new audience, and how sensitive you have to be, not only with the ideas themselves, but also how your audience needs to hear it. And thankfully, I have all this experience of talking on the microphone.

So, the rose petals. It wasn’t just a “reveal” for the sake of a reveal — you told a story with those rose petals. When you plan a reveal, what are the first things you think about?

I visualize and think about the feeling and emotion. Every drag reveal, or any reveal, needs to be an emotional feeling. When we learn new information or find a discovery or get surprised in real life, it triggers huge emotions for us. So that’s what it should be like on stage, too. With “So Emotional,” I came up with [the rose petals] from listening to the song, by listening to the beats. And you can feel — or maybe this is only because I think about these things now — you can feel that that’s the moment in a song where something needs to shift, or where something can shift and surprise people. I do it when I’m coming up with lighting cues for different performers’ numbers, too. Whatever music people bring, I listen to their description of what they’re going to do and the song itself. And so I’m usually looking out for the moments where something can shift. Like you said, it’s a story. We tell stories through song.

You still perform that number in your shows, but you’ve changed it up several times. It seems like it’s evolved and grown with you.

I would love it if that's true. I keep trying to make it fresh for myself. I love performing it, and it’s still fun doing it for an audience, even though no one is surprised by it anymore. But they’re delighted to see something that’s familiar to them. I still want to play with their expectations a little, or give them what they want in a more dramatic way.

Who or what were, and still are, your inspirations when it comes to a “reveal” in performances?

I was a Drag Race fan before I was cast, so I had seen Roxxxy Andrews’ wig reveal, which set the bar originally, and maybe even still. I’d also seen some of Raja’s performances on YouTube, and some Miss Continental or Entertainer of the Year performances for others. That’s how I first came across Sasha Colby. There’s a fabulous reveal that Nina West did for Entertainer of the Year, where the skirt of her dress comes “to life.” So I knew about the “art of the reveal” in drag for a long time. Leigh Bowery is another inspiration. There’s this incredible performance where they give birth on the Wigstock stage, in the late-nineties or whenever it was. It’s so good. [Bowery] has this giant belly in front, and it turns out there’s a human being upside down in it who crawls out at the end of the performance. That’s the sort of art I’ve gravitated towards as a drag performer. But something that intricate is hard to do in the context of Drag Race because you’re sequestered for filming. It’s hard to prepare something that you haven’t already brought with you. And I did bring a couple reveals with me — if I go back, I’d bring a lot more. I saw the “Lip Sync For Your Life” as a chance to prepare a realized performance to these songs. That’s how I approach drag. There have been some great reveals since my time on Drag Race. I loved all of Silky [Ganache]’s reveals from All Stars. Those were incredible. And Yvie [Oddly]’s reveals on her season, too. If you prepare, it doesn’t have to run dry. But not all drag artists are as insane as the rest of us about preparing a high-concept performance. And you can still give a great lip sync without having that. But for some of us, that’s the whole fun.

You watched the first season of Drag Race while you were doing a Fulbright in Moscow. In retrospect, there’s a beautiful intersection there, because you incorporate so much of your Slavic heritage into your drag. These days, what Slavic references are you drawing from?

I'm not really referencing Russian culture in my drag like I used to. I feel like now is not a moment to celebrate Russia. It’s part of my family story, too. My family had to leave that region. My grandma was born in China, because her parents were escaping pogroms in Ukraine, when it was still part of the Russian Empire. And when I was in Russia, it was clear that the leadership was incredibly fascistic and dangerous, and repressive. Of course, there's a culture and history of art that goes beyond that, but I don't need to give that attention right now. That said, I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that my family is from Ukraine, and how that previously hadn't registered as being such an important distinction. I guess that was the logic behind Russian Imperialism that made its way into my own head. There's not a strong Jewish tradition in Ukraine today because of, well, history. I’ve thought a lot about that, about those histories, and wondering how Ukraine could be a space for queer people, for Jews, for us to have a home in that part of the world again. It’s inspiring to think about. Maybe it's not my story to tell. But I’m very inspired by the resilience of Ukraine.

For those who may be confused or are looking to support or help those in Ukraine and Russia, how have you navigated your love and pride for your heritage with everything going on?

I think informing myself about the area, the history and the politics has been key to understanding that this conflation of Russia and Ukraine that’s been happening for so long is not how we should be thinking about it moving forward, and making clear distinctions when it comes to facts and information. I’ll always have solidarity with queer people, especially in Eastern Europe, because it's not very friendly to queer expression. No place is. And, in fact, Putin is using fear tactics towards trans and queer people as rationale for violence and Imperial violence against Ukraine. So, solidarity with queer people in Eastern Europe means solidarity with Ukrainian liberation at this moment. But I still have a lot of concern and connection to people living in Russia, who are queer as well, who are experiencing the same crackdown within their country.

I did a gig on a cruise ship last summer, and there was a drag queen from Moscow who was on the cruise, and some Americans were upset that there were any Russian people there at all. And that seems like a classic example of confusion. We need to have solidarity with everyone who is experiencing violence, and who cannot live their lives because of an oppressive and fascist government. It's not easy to draw lines, and we shouldn't be doing it from a nationalistic perspective. We should be looking at people and our experiences.

Your father is a published writer and scholar of Russian history. So the art of research and writing seems part of the family business. Was he helpful to you at all during the process?

My dad made sure that revolution — and in particular, the stories of working class people — was essential in my understanding of Russian history, and beyond. There are references to revolution everywhere in his house. The way that he approaches history is inspiring to me. I was just rereading one of my favorite books of his, Proletarian Imagination, which is a quasi-analysis of poetry by those who didn't think that they were making art but were making it nonetheless. And we can use their artistic creation to get a better sense of how they thought. I think [my dad] is a really incredible historian. His current project is somewhat inspired by drag, actually. He’s looking at city life in the 1920s, in Odessa, New York, and Bombay. He’s stepping out of his usual research. He loves the history of underground nightlife as well and looking at how queer people lived in cities during that time. I don't know if I inspired that, but he’s inspired me.

All this talk about revolution reminds me of something you once said, I think in a YouTube video somewhere, about being accused by the far-right of trying to “disrupt the American political system.” And you responded with, “Thank God, it’s about time!” I assume this holds true now, more than ever.

Yeah, definitely, and strategically so. I think that's one of the things that makes drag so special — its connection to radical thought. And the fact that we aestheticize radical life. And why not? Why not change the system? In some ways, I understand why conservatives find drag so threatening, because we do lead with a promise of a more inclusive world, or at least more inclusive within our own world. And that does require a radical change, or a radical reexamination of who matters and what is valid. And change is very scary for some people. Maybe it's scary for everyone. But drag says, “Oh, no, change is beautiful and fabulous and glamorous.” Revolution is fabulous and glamorous. In the book, I cite Angela Davis — of course — who says revolution or abolition is not as much about destruction — and I think that's what people are afraid of, destruction — as it is about reenvisioning the possibilities, creating something new, or an edit that makes things better, something more focused on humanity, more loving. Like, if you look at it that way, it becomes something necessary, not something frightening.

I was touched by the stories of your grandmothers, and how your Grandma Dina was the first to put you in drag for the first time. She really was the ultimate fag hag…

In her own words!

When doing research for the book and parsing through your family archives, were there any heirlooms you found, or anecdotes about your family, that you weren’t previously aware of?

I found this amazing picture in my grandmother's album — my other grandma, Josephine — of her brother in drag from the seventies. It's a faded picture that I remember seeing as a little kid, and that brought back memories. Even though I don't remember learning about drag, it was something that I knew existed and something no one tried to hide from me or shame it. And I recognize that that shaped who I am. And then most of the heirlooms in my dad's family are the stories. I have my own versions of the stories, and my dad has different versions of the stories, and his sister has different versions of the stories. So I would write down my version and share it with my dad. And he’d love my version, but he’d tell me that's not exactly how he remembered it. And so I tried to include all the disagreements and find a happy medium. But I'm convinced Grandma Dina told me the versions that I remember of our family stories.

You also kicked off a new Nightgowns residency at Le Poisson Rouge earlier this year, which is completely sold out through June. In the book, you stress the importance of local drag scenes. I see your joy in bringing the community together in intimate spaces. Nightgowns still retains that spirit of early queer nightlife. This isn’t so much of a question as it is an observation.

I'm glad. I think I do it half-strategically, like you say, because there's so much more to drag than Drag Race. But it’s also out of preference, because I love experimental or unexpected drag. And, you know, you don't really see much of that on Drag Race compared to what exists in these local scenes, so close to home, and the people who put in the work for these shows and take the opportunity to perform on-stage in front of a live audience seriously, which sometimes we forget. I’ve had my moments of devaluing that after Drag Race, but these are the moments where we can really connect and reach people. So that's what I love best about Nightgowns. And I’ll bring in the superstars as well. We just had Peppermint at the last show. So I keep my family, all my different families from the various stages of this crazy career, close to me. And we all fit together.

So, we’ve established that you’re currently in your “author era.” Where do you want to go from there?

Writing the book was something I really wanted to do, so it was a milestone, especially having written it myself. I am interested in doing something fictional. I feel like that's a big stepping stone. People wanted my real story, like the [Nightgowns] documentary and the memoir parts of the book. But I think we need some fictional stories about drag. So that's something I'm working on next. Also, a TV show or film with fictional characters. I think that would give me freedom to explore comedy and horror, things you can’t do in real life. I'm working on a new stage show aimed for Broadway or Off-Broadway. That's in development with Tectonic Theater Project, who’ve done several award-winning plays before. And that’ll be about drag, sort of inspired by the book, bringing to life some of these historical figures and parts of my own story as well.

You’ve maintained this wonderful career outside of the Drag Race franchise. But if you were asked, would you go back for an All Winners season?

Sure! You know, I think you have to know how to work the system and your opportunities while still staying true to yourself. That was my biggest challenge the first time. And I feel like I have so much more to use at my disposal to do that again. So if the opportunity arises, and I have a chance, and the paycheck is right, I will do it. Because they have the money!

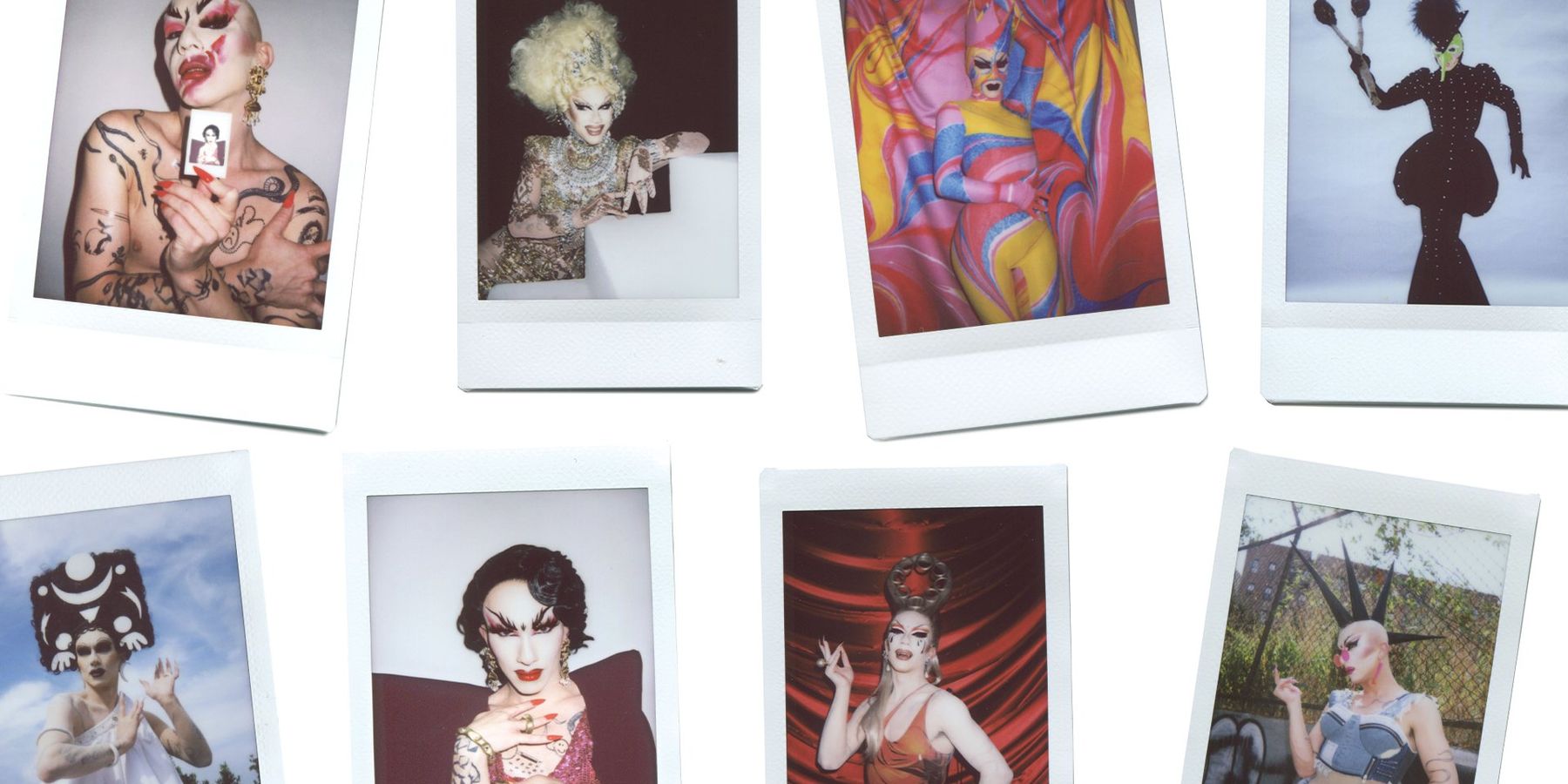

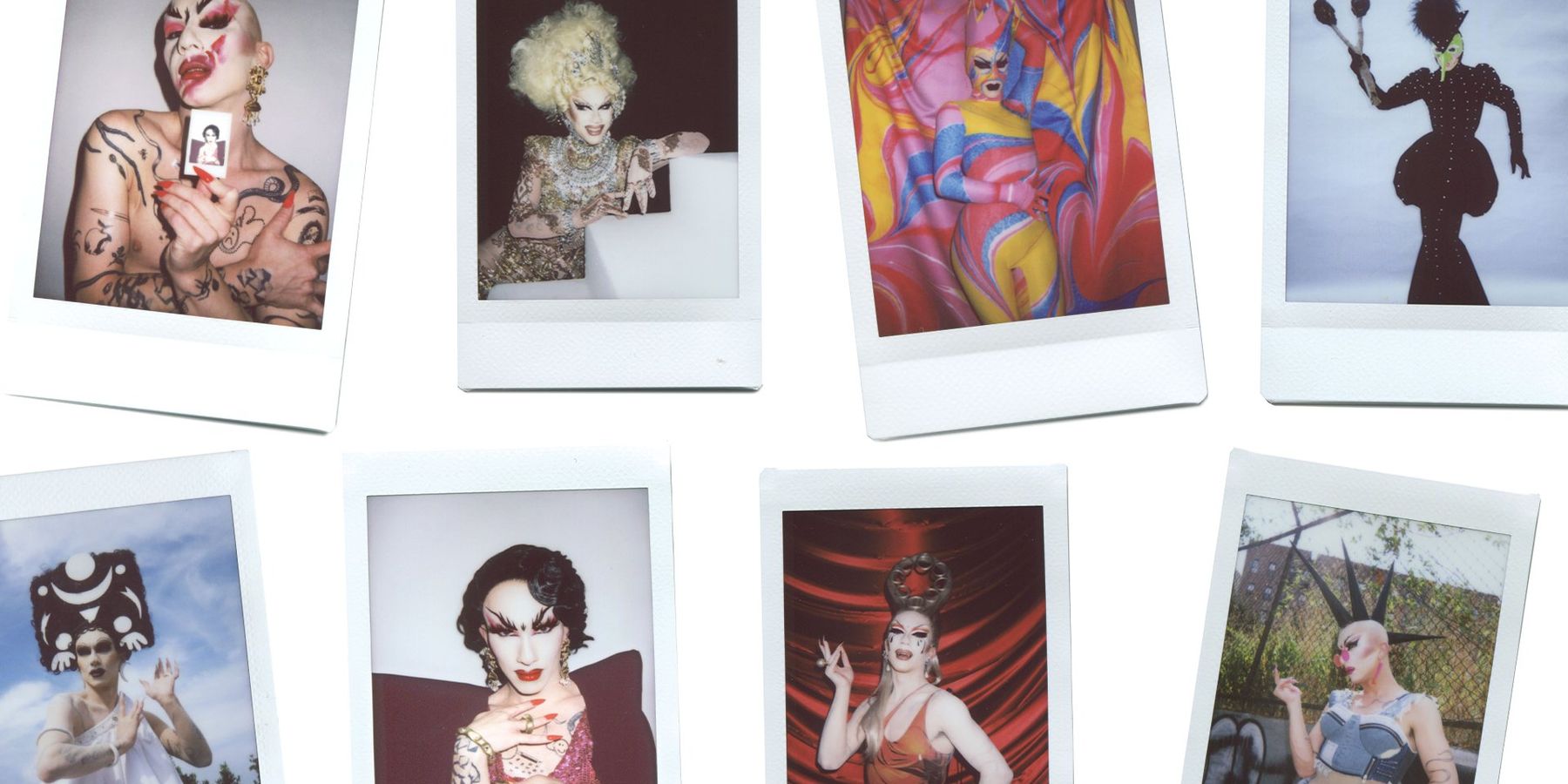

Photography by Sasha and Johnny Velour