Entertainment

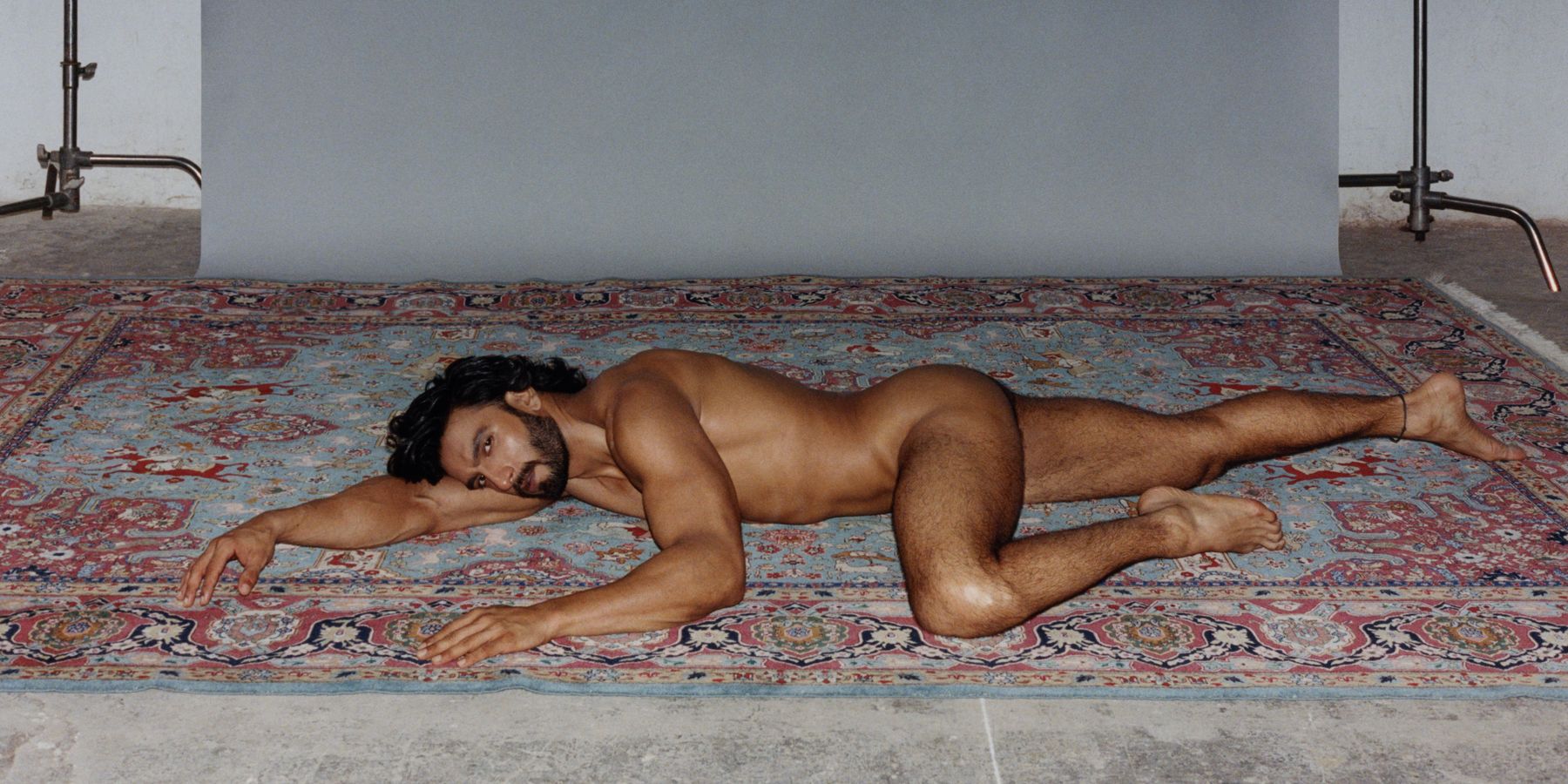

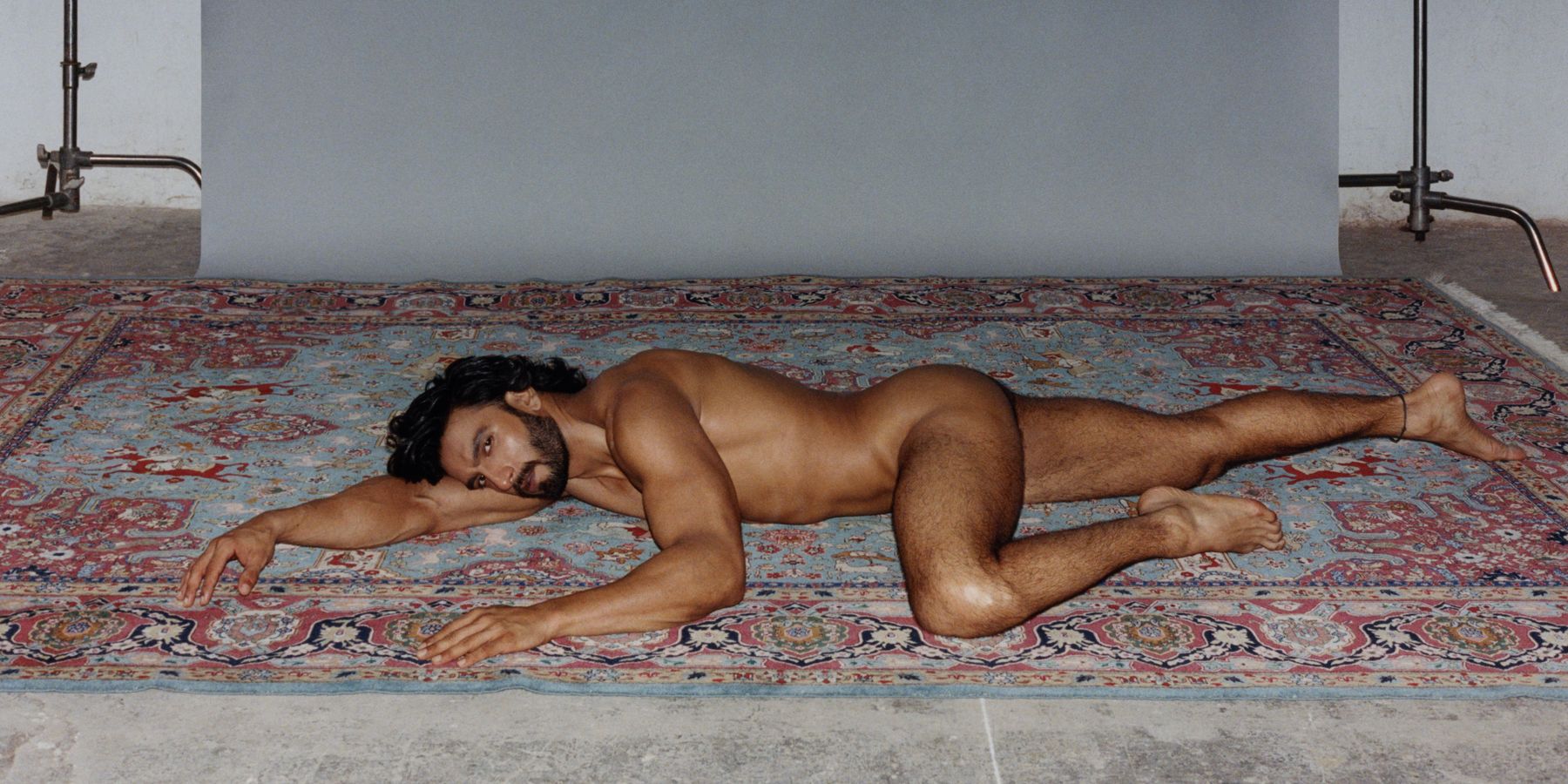

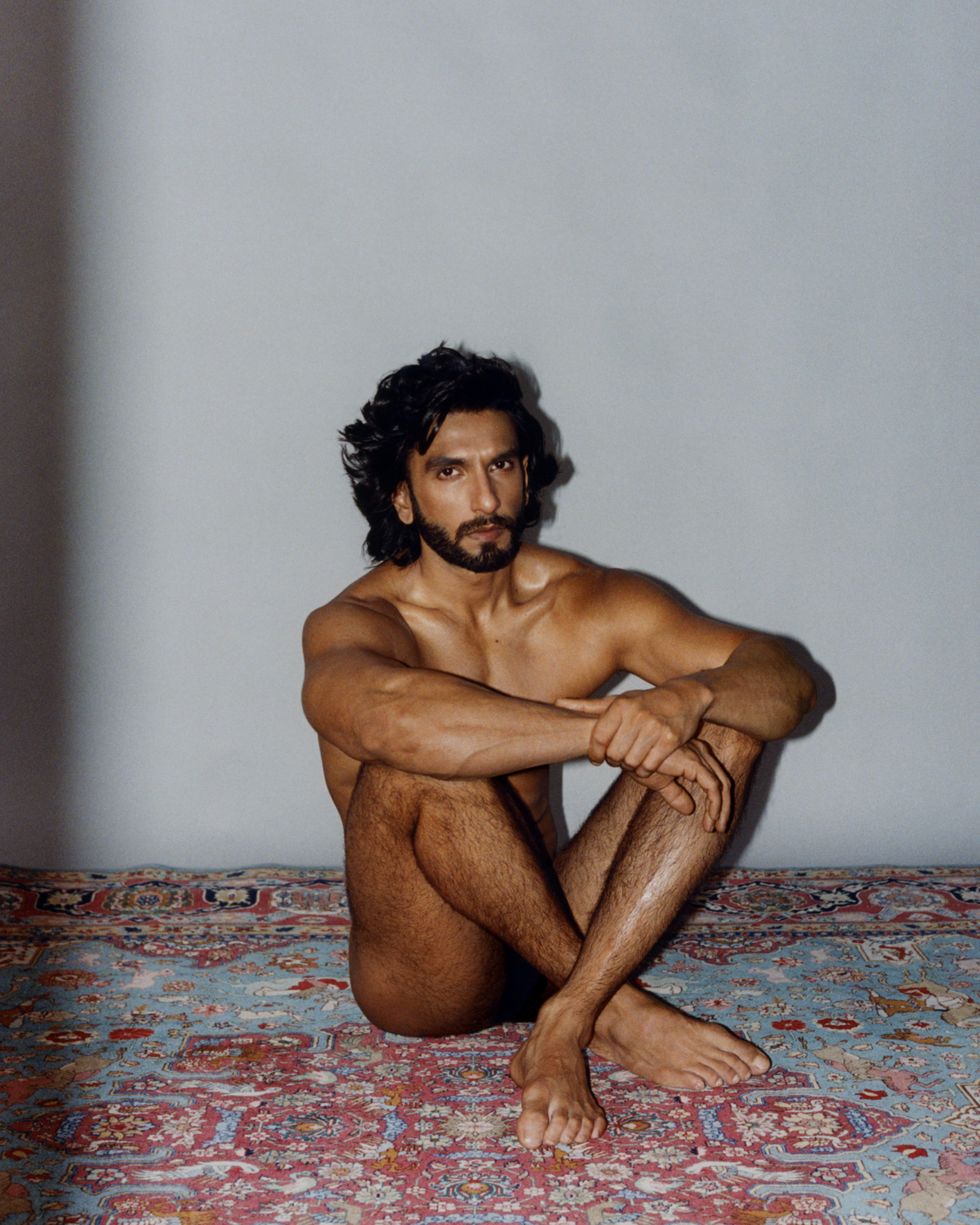

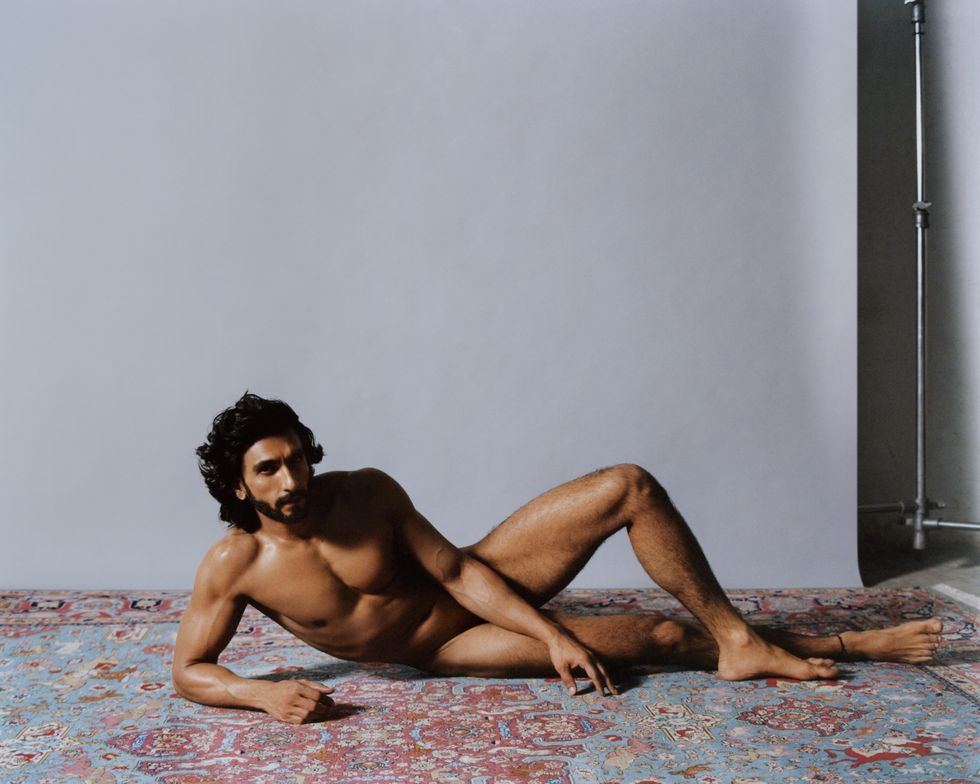

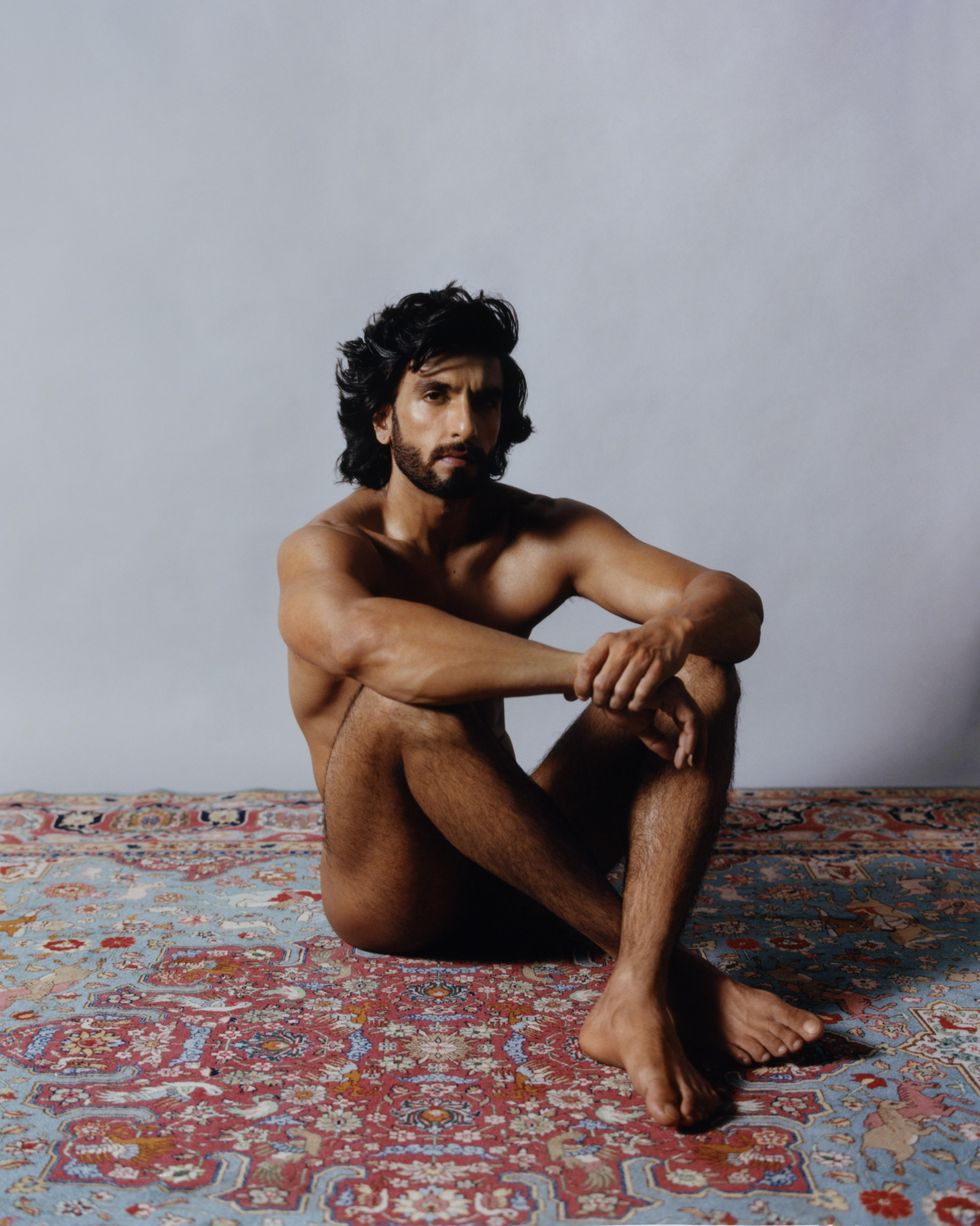

Ranveer Singh: the Last Bollywood Superstar

Photography by Ashish Shah / Story by Aishwarya Subramanyam / Creative direction by Kshitij Kankaria

21 July 2022

It’s a closed set on the PAPER shoot because Ranveer Singh is quite naked — although I can’t imagine he would mind people watching. I can’t actually imagine Singh doing anything without people watching. After all, who is a performer without his audience? If Ranveer Singh makes a joke in a forest and there’s no one there to laugh, does he even exist? What’s he doing in a forest in the first place (probably chasing after Bear Grylls to kiss him)? I’m pondering the deep questions while sitting at the craft table outside the studio, steadily making my way through a pile of potato chips.

Once the shoot is done, Singh walks around hugging people. It’s just what he does. He comes up to me and looms with a big smile, and I nervously ask if he’s going to kiss me. He does, a smack on my cheek. He is performing, as he always is. But it’s impossible not to like him.

Bollywood has never seen a star quite like Ranveer Singh. The immensely popular (and versatile) actor has challenged practically every stereotype of masculinity in still-traditionalist Indian society, all while remaining largely free of controversy and polarizing opinion (except perhaps when it comes to his fashion choices). There is a strong case to be made for the death of the superstar in show business, but Singh is the closest thing we have to one in this generation. He may even be the last of his kind.

Never before in Bollywood has an actor traded sexiness for slapstick, or enigmatic charm for friendly likeability. This is not to say Singh isn’t sexy or charming. In fact, he is both — just in a warm, wholesome, unthreatening way that dismantles toxicity entirely. He is smaller in person than you might expect, not unusual for movie stars. It’s his energy that takes up space and oxygen, making him seem bigger than he is, making you unable to take your eyes off him. He’s loud and obnoxious but in an endearing way, an excitable puppy that won’t calm down. What kind of monster doesn’t like puppies?

I meet Singh for the interview a few weeks later at the end of a long day, and have been waiting a couple hours for him. Normally this would make me grumpy, but he’s in the middle of a dubbing session and keeps leaving it every so often to say hi, have a quick chat and apologize. He compliments me freely, noticing my bag, my shoes, my style. It’s an effective strategy. When he’s finally done with work, it’s late at night and we are sitting alone on a couch at his studio with coffees. He is wearing a Gucci tracksuit and Yeezys and is flagging a little, but staying enthusiastic. “I’m all yours. I’m so all fucking yours, you could pack me up and take me home. I’m all yours,” he announces, settling in.

The one thing Singh aims for when it comes to his work is range; versatility is what he admires most in the craft, and he has picked roles accordingly. He’s come a long way from his debut as a rom-com lead in Band Baaja Baaraat (2010) and has given Bollywood some of its highest-grossing box office successes, including period dramas Bajirao Mastani (2015) and Padmaavat (2018) and masala entertainer Simmba (2018). “I’m just getting started,” he says. “For the past 10 years I’ve only been learning, I’ve been collecting the tools of my craft. Let’s just say I’ve accumulated enough to fill my tool kit, it’s now ready. I’m ready.” He’s had two releases since cinemas opened after the pandemic — cricket film 83 (2021) and Jayeshbhai Jordaar (2022), neither of which have been successful, but in which his performances received unanimous praise.

“My post-pandemic appetite for prolific work has become insatiable,” he says. “I’m so hungry for work, to do, to give, to perform, to ideate, to create, to collaborate. I have a ravenous appetite for work, I’m doing 20 hours a day and I’m damn fucking happy about it.” But the last two years have taken a harder toll on him, as on all of us. It lurks just beneath the surface when he speaks, an edge of madness that’s been freshly sharpened.

“I have a very dystopic view, a very cynical understanding of the world,” he says. “I really believe in the Ghor Kaliyuga, the worst part of the Kaliyuga.” The last and bleakest of the four world epochs in Hindu cosmology, the Kaliyuga is an age of strife and sin believed to last 432,000 years. And we’re only 5,123 years in. Or in Singh’s words, “Everything’s gone to shit. I understand that this journey of life is an agonizing fucking journey. It’s agonizing to just exist. I am hyper-sensitive to everything around me, it’s just the way I am, it’s how I’m wired [he’s a Cancer]. I feel a lot more. If I’m angry, I get really fucking angry, if I’m sad I get really fucking sad, if I’m happy I get really fucking happy. It is very difficult, and I get overwhelmed on a daily basis.”

This is Singh’s first interview in three years, and I’m well aware that my audience of one is sorely lacking. Between questions he gets up and jumps around, climbs up on the couch and walks on it, contorts himself into positions that can’t possibly be comfortable. He’s rarely still, and those few times that he is, when he searches for words, I find us being pulled into deep, heavy waters, dragged towards a darkness inside him.

“I feel like I’ve got FOMO about life. Something might happen if or when I’m sleeping. It’s not sustainable, and I realize that. Here’s the key,” he whispers, “I’m in an experimental phase. I want to see how much I can push myself. I want to see how much I am capable of doing – physically, mentally, emotionally. How fast can I go?” The “before I crash” is implied.

I see him clearly now: Singh is terrified of time, dancing for his life, running from death.

“I have an understanding of mortality. The eventualities of life and existence. I look at it like, what is this? It’s flesh, it’s bone. These aren’t my concerns. This is just a mortal vessel. My concern is with the energy, the spirit, that intangible thing that nobody seems to be able to explain. What is this energy that runs through you, runs through me, runs through all living beings. What is it? That’s the stuff.”

It’s not a side of him we see often, if at all. He’s too busy painting over it with silliness and noise. This sort of nakedness is unsettling. “It’s so easy for me to be physically naked, but in some of my performances I’ve been damn fucking naked. You can see my fucking soul. How naked is that? That’s being actually naked. I can be naked in front of a thousand people, I don’t give a shit. It’s just that they get uncomfortable.”

It's only much later while watching a video interview with film critic Anupama Chopra in front of a studio audience that I see flashes of this side of him in public. The crowd cheers his usual antics until he says, “I keep things light and low-brow and silly and slapstick… there should be humour and a lightness of being. And sunshine, you know? I reserve the darkness for myself. God knows I’m a dark guy, I’m really dark… yeah.” There’s an awkward silence, and he pivots quickly to, “See? No cheer for that. Hmm.” The crowd laughs, and is his again.

This dichotomy in him is perfectly illustrated by the clarity in his separation of private and public. “I like minimalism in my spaces and maximalism in my appearance. You go to any space that’s mine, it’s completely sparse, painfully minimal. And I’m very protective of that. I’ve never shown the world my personal spaces. Never. Not a single picture of me in my house. When guests come over, I ask them not to take any pictures. You’ll never see my house in AD. I just want there to be a space that I know is free of eyes. There are only a few spaces left like that for me.”

His style is quite the opposite, and has invited its fair share of derision. Dabbling in gender-fluid or nonconforming fashion has prompted comparisons to Harry Styles, and he has worn more and more outrageous (for Bollywood, anyway) outfits over the years. It’s been fun to watch him play with fashion, to debate whether he’s being ironic or earnest with his clothing choices — the answer lies somewhere in between, like Singh himself.

Currently in his maximalist Gucci era, he doesn’t see why he shouldn’t be. “I work fucking hard. I want to wear nice shit. Eat my fucking ass, I will wear nice fucking shit. I bust my balls, I work 20-hour days. I’m not complaining — I’m only too happy and too grateful — but I go fucking hard. I will fucking buy Gucci, I will wear it from head to toe. Anybody who judges me can eat my fucking ass.” Amen.

Photography: Ashish Shah

Creative direction:

Kshitij Kankaria

Creative direction assistant:

Keshvi Kamdar

Hair:

Darshan Yewalekar

Makeup:

Tarannum Khan

Production:

Imran Khatri Productions

Carpets:

Jaipur Rugs

Editor at large: Mickey Boardman