Pierre et Gilles Still Reflect the World Today

By Harry Tafoya

Oct 10, 2024The first art book I ever purchased was a beat-up copy of Pierre et Gilles: L’œuvre complète (1979-1996). It took several weeks of toiling in my hideous temp job before I could afford it, but eventually it was all mine. On days off I would poke my head into Dog Eared Books in San Francisco to marvel over its pages before stashing it out of the way so that no one else could find it. When it wasn’t hidden among travel guides and cookbooks, the shop owner would return their book to its usual place: halfway between the Fine Art and Pornography sections. After the first couple of times I’d done this, he gradually began to include Post-Its telling me to: “Fucking cut it out.”

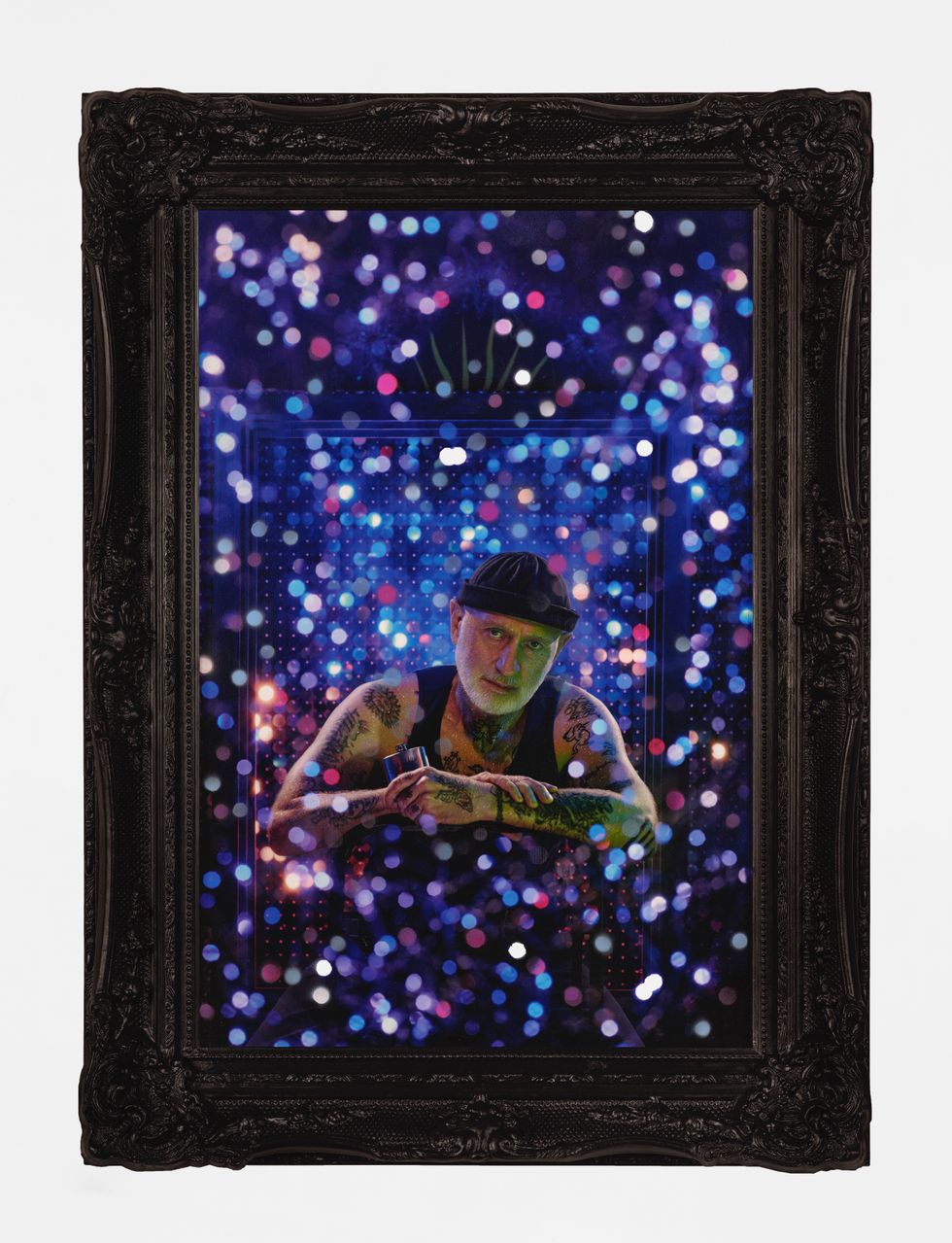

Looking back, the French duo’s photographs were like a portal, a window out of the city and its sterile, tech-bro minimalism into another dimension altogether. My memory of this time was of a chrome-plated metropolis, going to work in soulless skyscrapers and catching distorted glimpses of myself in empty, ultra-polished storefronts. Pierre et Gilles’ work was just as reflective but much warmer. They were among the very first artists who taught me that shiny surfaces could not only be transportive but made for looking at deeply. Like Jeff Koons, Pierre et Gilles’ work is stunningly superficial, charging past any safety marker of good taste, until the extreme end of camp gives way to full-blown supernovas of kitsch. Even though their art begs to be taken at face value, at its best the duo bypasses the folds in a viewer’s brain to access a smooth and infinite horizon of airbrush, sparkle and gloss.

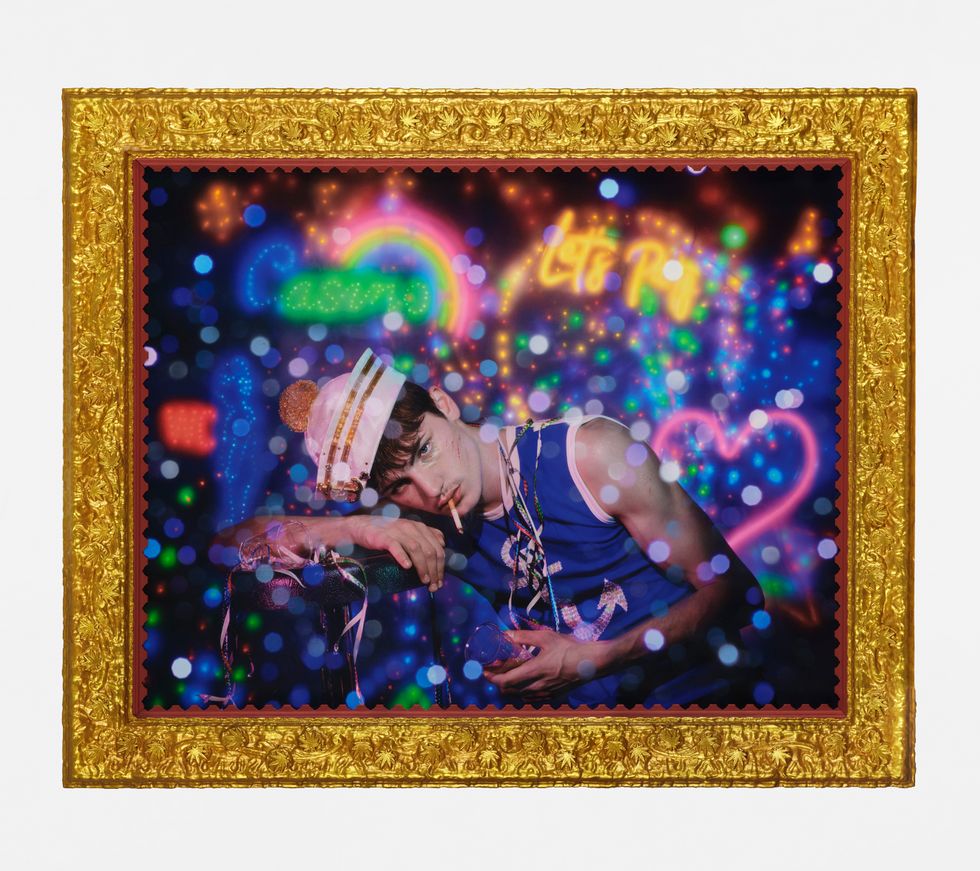

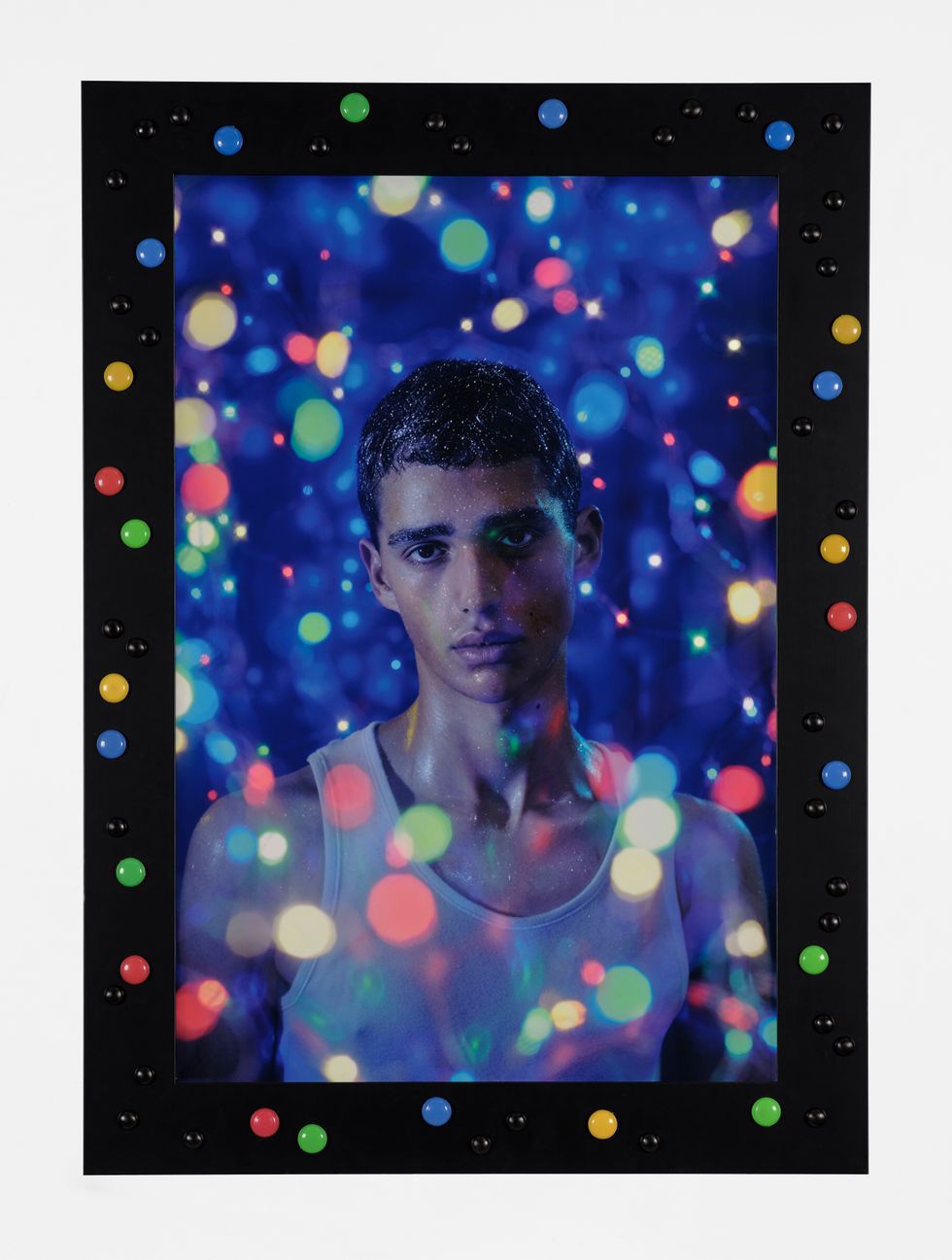

Portraits by Pierre et Gilles exist in a parallel neverland, where impossibly beautiful subjects are eternally game to play dress-up and forgo their (often very public) identities to become one with the shimmer. Their aesthetic is like a Blob from outer space or an ever-expanding City of Oz, capable of absorbing everything in its wake until it re-emerges on the other side in dazzling, romantic Technicolor. Realism has virtually no place in the artists’ universe, so they communicate what matters through other strategies: visual puns, deadpan humor, loaded cliches. When a model smiles, the whole world smiles with them; when they frown, the heavens weep. It’s frankly impressive that the all-too frequent male nudity is somehow less faggy than their knack for constant, fabulous overstatement.

If I had a more conventional art education, I’m sure I’d have been conditioned to gradually hate their work, faulting them for its perfection rather than appreciating it. Sleekness is Pierre et Gilles’ signature, and for some that’s simply not enough to hold onto. But look closer and you realize that their sheen is the synthesis of many component parts: the light and color of James Bidgood photographs, the barely contained joy of Jacques Demy films, the fully-realized fantasy of Jean Cocteau and Bébé Bérard productions, the rhinestone flamboyance of a Paris cabaret revue. Even if French intellectuals were the first to grapple with postmodernism, French artists were invaluable as practitioners of it. What Baudrillard, Derrida, and Foucault explained in dense theoretical language; Mugler, Gaultier, François Ozon, Jean-Paul Goude and Pierre et Gilles brought to life in infinitely more fun and immediate ways. You only need to take a look at one of the duo’s pictures to see how they erase the boundaries between high and low culture, de-center the self, remix iconography and re-write the world in quotation marks to understand how totally they nailed their moment.

Since then we’ve drifted into an infinitely weirder era. The symbols that Pierre et Gilles once used freely now feel more loaded than ever. The same tone of gleeful camp has gone mainstream and beyond the bounds of queer culture, becoming an empty vehicle for politicians to dehumanize as much as empower. There are more tools than ever to make mythologies around ourselves and even greater platforms for sharing it. After 40 years, Pierre et Gilles’ mission as artists feels consonant with a generation of internet personalities who’ve buffed and flattened themselves into their own shiny set pieces. At the same time, the duo’s best work isn’t about self-promotion but how elastic and mutable one’s image can be, while remaining a glittering counterpart to a world that feels overwhelmingly real.

PAPER sat down with Pierre et Gilles at the PUBLIC Hotel to discuss their decades-long career on the occasion of their latest show, Nuit électronique at Templon in Paris.

One thing that I think is really interesting about your work is that there's a number of subjects that are very eternal that kind of come up again and again and I'm curious why they've stayed with you. I'm thinking of street urchins, sailors, working class guys, Querelle de Brest.

Gilles: Well first of all, we both come from the sea. We come from harbor cities. The sea, the boats, that's the entire universe of our childhood that's inspired us. Querelle was not an influence in the first place, it's really just our childhood. I'm from Le Havre on the Channel. And in a way Le Havre and Brest are not that far away. They're both cities that had been completely rebuilt after the Second World War and they're both sitting on the sea.

Pierre: The first book I ever read was The Little Mermaid. It was one of those books with a vinyl record, so you could hear someone read the story and there were lots of images.

Gilles: And as a child, I was always fascinated with sailors. We would see them all the time and the boats would come, they would disembark and crowd the city. And also through films like, for example, Jacques Demy movies like The Young Girls of Rochefort.

Pierre: And there was this legend that if you touched the pom on their hat it was good luck.

Gilles: What's funny is that as a child I thought their uniforms were really cute with their little pom-poms, and I never thought they were actually military men. It never occurred to me.

As you've returned to these subjects again and again, has your approach towards them gradually changed?

Gilles: The sailor is a figure that has inspired lots of gay artists — Jean Genet, Jean Boullet, Jean Cocteau were all very much influenced by that figure of a sailor. It's a recurring theme in gay culture. It's a figure that, you know, brings fantasies. And we were touched by the same imagination as those other artists.

When you have these newer, younger models, are you trying to map them onto your own fantasies?

Pierre: It's always in exchange. It's always a dialogue. They enter into our world and we enter into theirs. It's always a negotiation. They inspire us and through them, we try to express something. It's always tailor-made. It's always based on their own personality, how they can fit into that narrative. We're never going to have them play a role if we feel that they don't fit into that character.

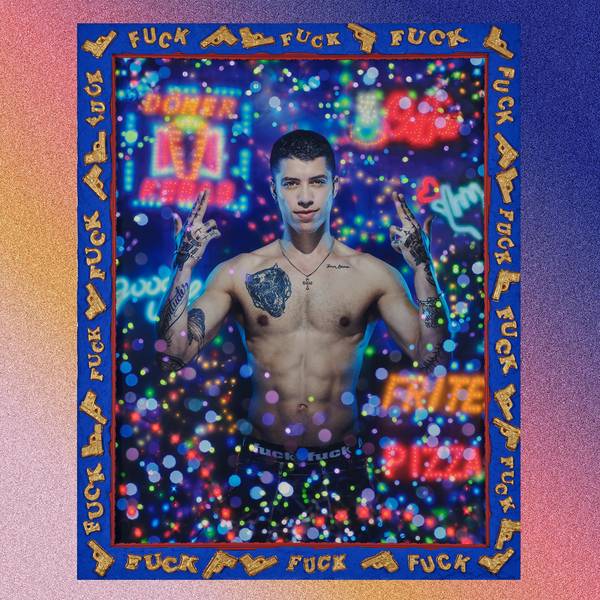

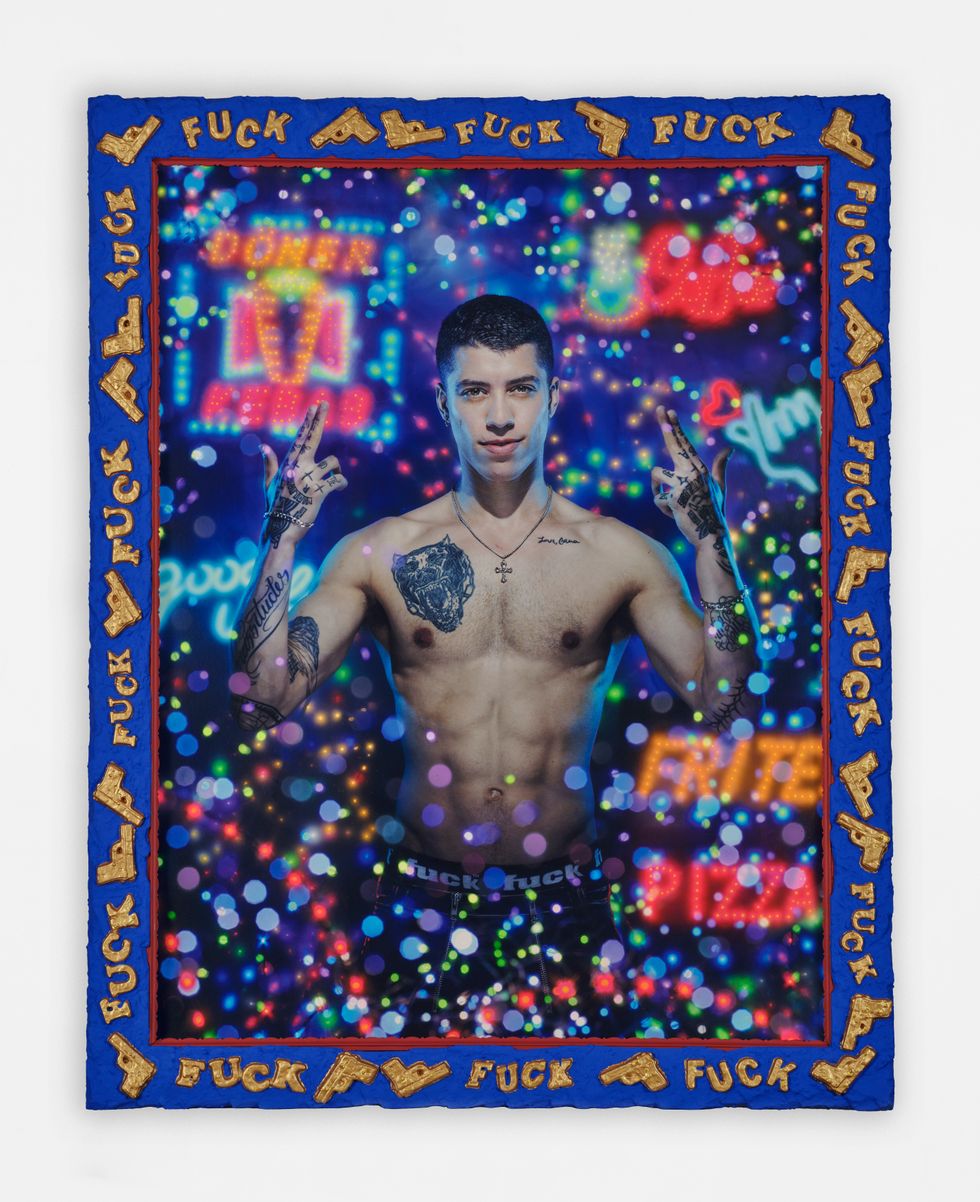

How do you reach out and find new models for your work, like Jonah [Almost], for example?

Pierre: We met through Instagram. We were supposed to do a photo shoot with [a different] gentleman, and Jonah, who was also in Paris, [also] came to the studio, and so we decided to do a photograph with the two, and then that's how they built a relationship. And then we did a new one just with Jonah for this current show. He calls us his "daddies," he's become a good friend.

I'm also curious about models who you've worked with multiple times, like Isabelle [Huppert]. Do you initially have something in mind for her or do you collaborate together?

Pierre: It's based on her own story. It's also based on her own life. She invited us to see her show on the life of Mary Stuart that she was playing on stage and we wanted to do our own Mary Stuart. And she was also interested in experimenting a new dimension of that role, very different from the actual play. We love working with her.

Gilles: We had worked with her previously on the film Souvenir and she was playing the part of some kind, like a singer, working for this contest, like Eurovision. So we wanted to do an image but that served later as the billboard for the poster. And the very first image was a very personal image. Based on Ophelia but Ophelia in the year 2000. She's able to embody so many different parts. She's able to express a wide range of emotions. She loves photography. She understands the work of photography. She always wants to push for boundaries. She always wants to go further.

Could you tell me about how you treat yourselves as subjects in your self-portraits?

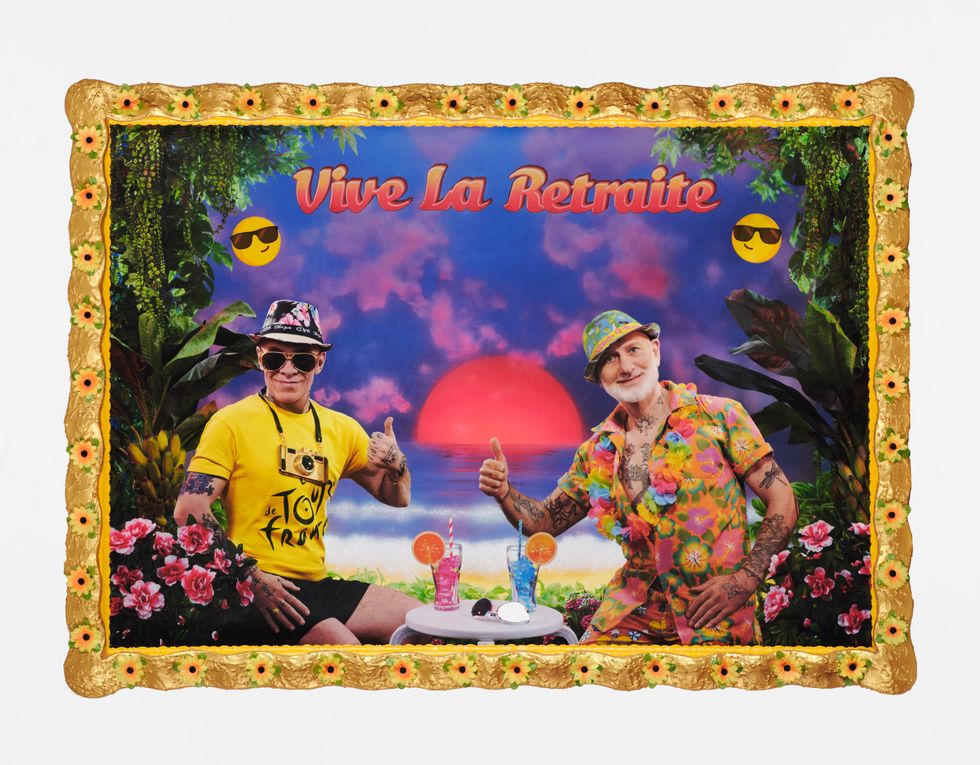

Pierre: Self-portraits, you know, come at irregular times. We don't do them so often. Sometimes we feel there are certain ideas that we can only express through our own bodies, our own faces. This is not what we like best. We don't do them that often, but it's like punctuation for our oeuvre. It's one of the most difficult exercises that we have to do. For example, last year, there was this whole controversy about the age of retirement, they wanted to have it higher and there were demonstrations on the street. It was a big thing politically in France, and we wanted to take that subject of retirement and imagine ourselves as fictitious retirees. We wanted to treat this very heavy subject with humor.

Gilles: We understand why people do not want to lower the age of retirement. But first, it's not the topic that concerns us, you know, we as artists, we want to work as long as possible. We felt we could use the subject to do this kind of tongue-in-cheek representation of this whole political debate in France.

Some of your work actually does get into very hot political debates and approaches them in a very tongue-in-cheek way. “Jonathan and David,” for instance.

Gilles: Oh that is not an image you can put on Instagram, even if they're not naked. It represents Palestine and Jewish people, you know, like hand-in-hand, like an embrace. It's a message of peace mixed with homosexuality and nudity. So it's like three subjects that can really be explosive. You can show it it in a book, you can show it in an exhibition, but on social networks it is just not possible. We're aware of that. It's sad, it's a shame, but that's the way it is. There are some images that we have to accept. Anything that has to deal with nudity, for example, is a problem.

For an image like that, have you as artists had to change your approach toward what political subject matter you'll take on?

Pierre: No. We always do as we want. We work with our heart.

Gilles: We show them in exhibitions. And, of course, sometimes people photograph them, and they may find themselves censored, you know, on their social network. The mayor of Brussels, for example, when we had a retrospective in Belgium, he loved that image [Jonathan and David], and he posted it on his Facebook or Instagram account, and the mayor himself got censored, and he was shocked that this would happen to him. He told us the story of how he had been banned from Instagram for a few days because of that.

It seems like a lot of your style and subject matter comes from some really deeply French traditions. I'm curious how you treat that subject matter with the rise of extreme right, nativist politics in France.

Pierre: Yeah, our work was always inspired by a lot of cultures. We went to India, we went to Morocco, we went to Asia, and many of our images bear the inspiration from other cultures. This is very important for us.

Gilles: Of course, we have our sensibility because we're French, you know. But for the rise of nationalism or national identities, our work plays a role in French society of a message of freedom, of tolerance, to bring a bit of joy, a bit of happiness and humor, also a bit of humor. In this world where people just keep fighting, and where this world of division. But this is really a global problem.

Do you think that your audience is responding to your humor the same way that they would have years ago?

Pierre: I don't think the audience has changed their perception of the world. Our audience is lots of young people and older people. We really are transgenerational. We try to speak to everyone. Our work is really about creating connections between people. I think that it does that. It carries that role. We're always surprised at the diversity of people who love our work.

Gilles: And for example, I was really surprised to see that Sébastien Chenu, who is a politician of the extreme right, is following my Instagram account. So you see... but we don't follow back. I was shocked. If it can help change people’s mentality, that's just as well.

That just reminded me of that one far-right politician Julien [Odoul] who did cam work and posed for [the gay magazines], Gab and Têtu.

Gilles: There's lots of gay people in all parties of Parliament, you know, no difference.

The Prime Minister [Gabriel Attal].

Gilles: And it's good that the Prime Minister was really open about it, because it changes peoples’ mentalities.

What do you think about the gulf between mainstream gay politicians and the more avant-garde gay figures that your work draws from? How do you feel about the space between them?

Gilles: Never believe appearances especially in politics. Maybe this Prime Minister dreamt of having just a big [Pierre et Gilles] work in his living room. Maybe he has one. Private life is very different from what you show to the public sphere of politics. There are lots of things you don't know about people.

How has your technique gradually evolved?

Gilles: As a painter, you know, the main thing, of course, was format. Because in the beginning, images were printed on C-prints, so the format was small. Like for a magazine or a record cover.

Pierre: And we started to have shows like art shows and exhibitions a bit later.

Gilles: We started working together in 1976, but our first gallery show was in 1983, so it took some time. So in the beginning it was like small sizes that were adapted for press or magazines and as we began to make art shows our format started to get larger. For a long time, they remained C-prints, but after the technique evolved, we were able to make large digital prints directly onto canvas. And the size could really get a lot larger. I was so happy to be able to paint directly on canvas, you know, I went to the School of Fine Arts. I used to be a painter, it's easier to manipulate and it's much more sensual, and for the last 10 years, we've been working with a digital camera but everything remains artisanal, like craftsmen, I still paint only with my brush. I can get more vivid colors, more precise colors.

Pierre: And also the photo shoot, like the actual photo shoot has evolved over time, the space got larger, the workshop, the studio got bigger. The sets could change. Sets could get bigger and also the cameras evolved. So even the way the photo shoot was organized, with lights and the camera, also changed over time.

Gilles: What's very interesting now is to be able to work on the screen during the photo shoot, because now I can see the footage as we're taking it, and also the model can see it can reassure the model. So that helps with the psychology of a pose, you know, and before I couldn't see what I was going to paint. We would have Polaroids but Polaroids are not the same thing, it gave a sense, but it was not like seeing the actual image before it's shot.

Now that scale has increased, it's also shrunk. How does it feel that it now is diffused online?

Pierre: We're very happy. You know, before it used to be distributed through the press a lot, or books. And now it's a bit more direct, but it's the same principle. We used to receive letters, like we used to receive lots of mail, and now we receive DMs on Instagram. It's a great way to diffuse your work. In the ‘80s, you know, it was Taschen books that got us exposure internationally. It was distributed all around the world with very cheap art books. This is how we got famous in the first place. And now, you know, social networks have replaced that. But what's really important is to see the image in the flesh, because the pictures are very different from what you see printed or on the screen. When you get close to the image, you get to see the paint surface. It's a completely different experience,

You kind of answered this question before, but would you guys ever retire?

Pierre: No, of course not. But artists never retire.

Gilles: I would be afraid of getting retired. Not being able to work would be a disaster.

Photos courtesy of the artists and TEMPLON, Paris - Brussels - New York

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October