There are a handful of well-known gay and lesbian North American country musicians today, but the visibility of their identities, while brave and important, still exists within the mainstream industry — within which the conversations an artist can present are limited to commercial palatability.

Besides a few exceptions (k.d. lang, for one, and more recently, RuPaul's Drag Race All Stars titleholder Trixie Mattel), to find unabashedly queer country music — and it does exist — you'll need to look beyond the major labels and outside the charts. One of the most radical of those acts is Lavender Country, a group responsible for what's considered the first-ever gay country album.

Bearing the eponymous name of his band, Lavender Country, founder Patrick Haggerty, now 75, tells PAPER he had no chance of industry recognition. He'd deliberately packed it full of concepts and ideas he says were "beyond the pale."

"Not only is it like, who ever heard of gay country? But you're talking about a socialist, feminist, revolutionary gay country artist. It was absurd," Haggerty recalls.

Only surviving photo of original '70s Lavender Country band.

Sexism, fascism, Black liberation, socialism, revolution, white supremacy and heteronormativity, and, of course, gay love — and the connections between those topics — are all addressed on Lavender Country. Most shocking, though, is the ballad "Crying These Cocksucking Tears." It's the song Haggerty credits as rendering him "untouchable."

"No musicians, straight or gay, nobody asked me to play Lavender Country, or to join them in any musical venture, for decades, decades," he recalls. "It's like I was completely poisoned."

He lived without regret, spending the bulk of his life dedicated to activism, from Black liberation to gay rights and socialist, radical politics. Only recently had he found his way back into music, playing covers for Alzheimer's patients at senior centers. Married to his partner of more than 31 years and, to an extent, "back in the biz," Haggerty was, by all means, content — still, though, he describes a lingering "pang" that Lavender Country wasn't heard.

Flash forward to 2014, when North Carolina record label Paradise of Bachelors finds his music on YouTube, then reissues it — to widespread critical acclaim. He's touring now more than ever, sharing stages around the U.S. with queer country and Americana acts like Paisley Fields and Secret Emchy Society. A few months back, he played a surprise set at masked crooner Orville Peck's show in Seattle.

"All these other gay country artists are emerging, and seeing me in ways that I never saw myself — like the granpappy of the genre," Haggerty says.

Ironically, "Cryin' These Cocksucking Tears" — the song "that stained Lavender Country forever," as Haggerty describes it — is now his signature; an unrivaled crowd favorite.

He describes the change through the Marxist concept of dialect: "It's when something turns into its opposite. It's a recurrent theme about how to make revolution. The lowly working class ends up ruling the world; it turns into its opposite. Because I'm a Marxist, I look at things dialectically because it's part of understanding how revolution functions. And dialectically, my song, 'Cryin' These Cocksucking Tears,' turned into its opposite."

Haggerty has also been the subject of several short documentaries and has collaborated with San Francisco's Post:Ballet dance company on a Lavender Country ballet. There's also a Hollywood biopic about Haggerty currently in the funding phase, and it stands to be quite compelling.

Growing up poor in a small Washington town near the Canadian border, Haggerty worked the family's dairy farm; a very tight and overwhelming operation, he says. It's not a scenario one would imagine as welcoming for a queer kid, but in fact, his father loved him unconditionally. Haggerty wasn't out, but his father knew, he says. And having raised multiple siblings before him, he'd honed certain principles in parenting — recognizing the individuality of every child, and loving them as they are, was the crux.

"My father imbued me with such confidence and such permission and such ability to have pride in myself and the talent that I had, that I ran around in drag in a bailing-twine wig, and ran with all the girls, and competed with them in the cooking contests," he says.

The Haggerty family circa 1945.

Haggerty credits that loving upbringing for the acceptance he was fortunate to experience in high school. In high school he was voted head cheerleader and served as president of the senior class, he says: "I was president of any club I wanted to be president of all through my childhood. Everybody knowing exactly who I was; everybody knew I was a sissy in the county. It all emanated from my father."

Later in life, though, Haggerty endured the inevitable repercussions; in the late '60s, he was booted from the Peace Corps. "It's my crowning glory," he laughs. "I have another first before Lavender Country — the first person to be kicked out of the American Peace Corps for being gay." Though Haggerty recalls this with humor, he notes that it was "a very traumatic experience." Politically, it transformed him.

Prior to entering the service, he'd hitchhiked from his hometown and fallen for a Native man on the way. Returning to Missoula, Montana, hoping to rekindle that romance, he ended up working in the county's welfare department. Soon after, news of the Stonewall Riots broke, and within days of the June 28, 1969 events, Haggerty publicly came out.

"I just couldn't stand it one more minute," he says. "I came out, basically by myself, but the hippies supported me."

But bravery and fear can coexist; one does not annul the other. "I was scared out of my mind," Haggerty says. He found protection in a local motorcycle club, bonded by shared traits of rebellion, courage, and guts. Having spent a summer riding with the bikers, he credits them with having saved his life.

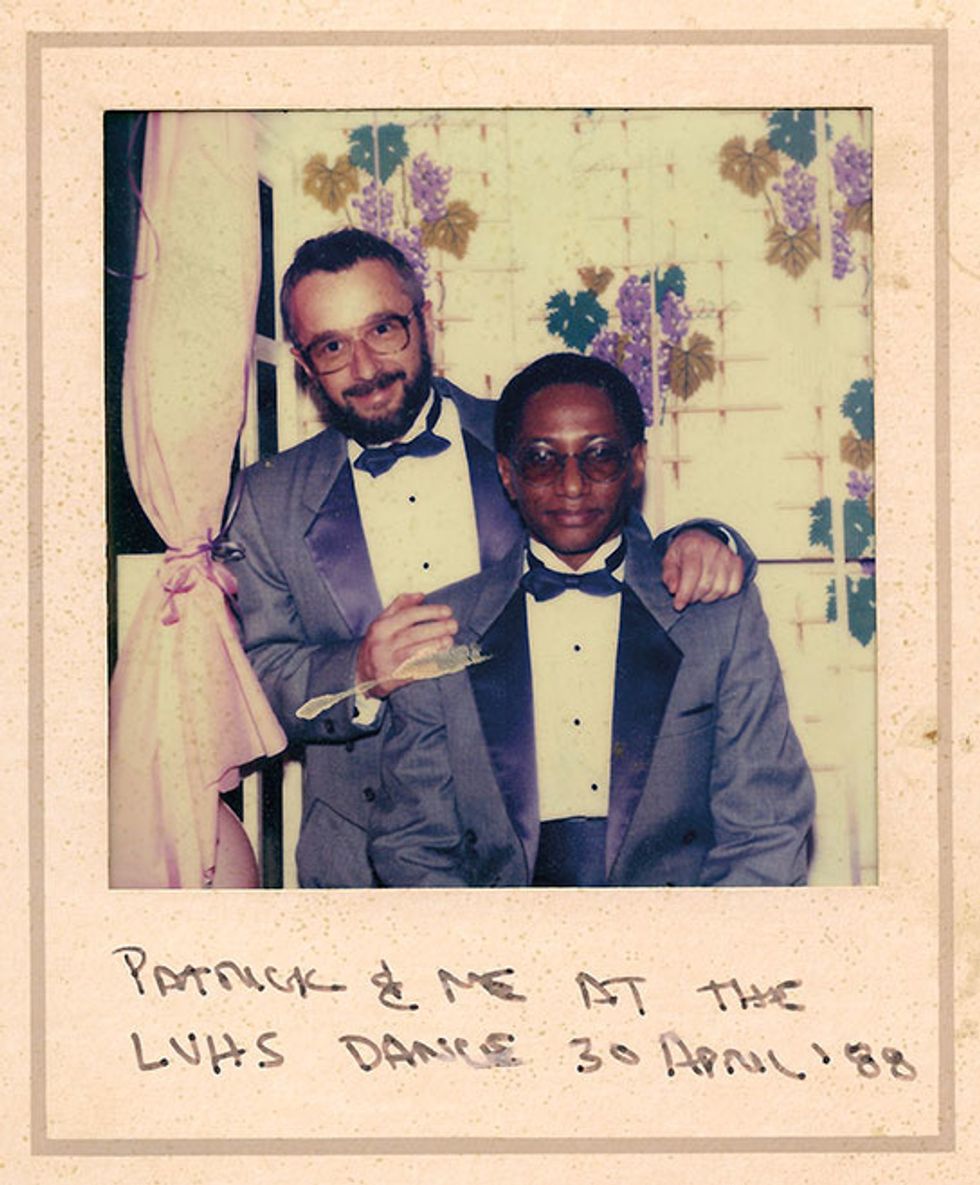

Patrick and husband JB at LVHS Dance, April 30th 1988.

"We would ride around — six, seven, eight motorcycles at a time — and I'd be on the back of somebody's motorcycle, and they'd roll me down the Main Street of Missoula with scowls on their face, like, if you touch one hair on his head," he laughs.

Relocating to Seattle for graduate school, Haggerty immersed himself in the gay liberation movement. It was through the support of the radical activists he found there that Lavender Country was created: It was the community who helped see the album to fruition.

"Somebody managed it, somebody figured out how to get it to a studio, somebody raised the money, and somebody put the ads in the underground papers, and somebody rented a post office box," he says. "Somebody put Lavender Country in mailers and mailed them out for $4 a piece. I didn't do all that myself. The movement did it."

Musicians featured on the record were part of the community, too — like Eve Morris, a Jewish lesbian activist originally from Miami who contributes its one wholly folk number, "To a Woman," and also pianist Michael Carr, who "had a more Marxist and working-class orientation." Then there's lead guitarist Robert Hammerstrom, who Haggerty notes is not gay — whose background as a professional ballet dancer somewhat prepared him for the Lavender Country experience — and later carved out for himself a career in country music, running a small label and working as a recording engineer.

Haggerty isn't in contact with the latter two, but he has reconnected with Hammerstrom. Together, they've completed a new Lavender Country album, Blackberry Rose; a crowdfunding campaign is ongoing, and a single, "Gay Bar Blues," has been released. Some songs date back to the Stonewall era, while others were penned later — he never stopped writing — and a few are newer.

It took nearly 50 years for country's powers-that-be to recognize Lavender Country as the first gay country album. Recognition from the Country Music Hall of Fame and CMT in emphasized in his label and press bio -- but it's probably not Haggerty who's pushing the mentions. Because for him, Lavender Country was created not for a mainstream industry shake-up, but as a vehicle for social change.

"That is the function of the album: It's to advance revolutionary consciousness into the public. That's why I made it," he says.

Touring around the country, Haggerty notes, he's gathered a crew of musicians: He's got a band in Seattle, one in Portland, another in San Francisco, and so forth.

"At this point, there are 50 or more really good musicians across the country who have performed with me," he says. "The thrill of the Lavender Country story is that I get to use Lavender Country, finally, for the exact reason that I made it in the first place."

Photos courtesy of Lavender Country