PAPER People 2018

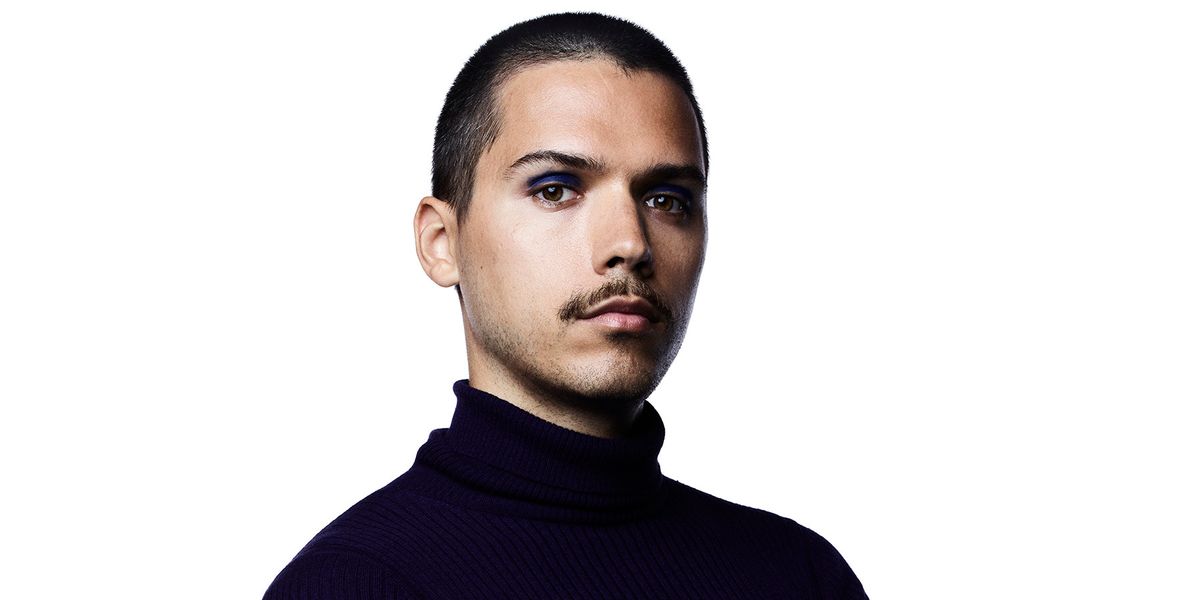

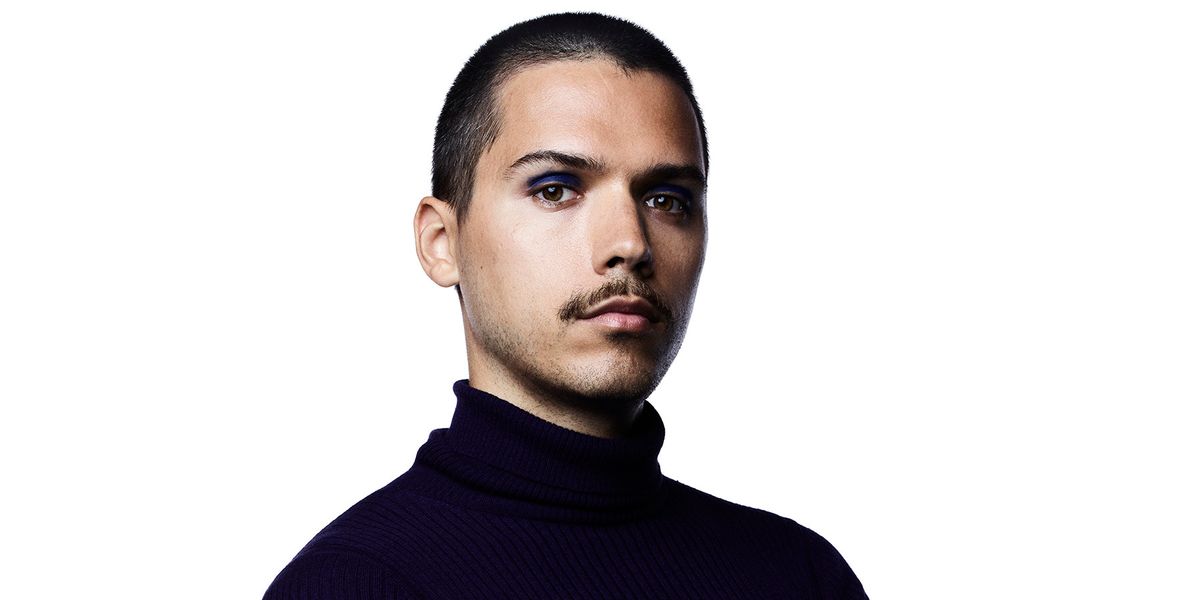

PAPER People: Harry Nuriev

Story by Shyam Patel / Photography by Ben Hassett

04 September 2018

PAPER has always been a place of opportunity, a place that spotlights new talent and people who are doing tremendous things. We've spent over 20 years bringing you the Beautiful People issue, which identified amazing people who were doing things differently and using their creativity, ideas and success to transform culture and create new opportunities for artists, audiences and fans. This year, we have decided to rename the portfolio and call it exactly what it is: PAPER People. — Drew Elliott, Editor-in-Chief

Related | Meet the 2018 PAPER People

Harry Nuriev — the Russian architect and designer behind Brooklyn-based firm Crosby Studios — has been dubbed an Instagram-era creative by The New York Times. While his buoyant take on minimalism makes for attractive social media fodder, his furniture, objects, interiors, and installations are created for more than fleeting digital moments. With deep-rooted memories central to his process, the 33-year-old endeavors to create spaces that become abiding memories for those who pass through them.

Nostalgic vignettes from Nuriev's childhood in Stavropol, Russia — a city in the Northern Caucasus nestled between the Black and Caspian Seas — inform the New York transplant's mirthful approach to color and soften his streamlined aesthetic. Sinuous shapes and the juxtaposition of rough and refined elements bring warmth to his function-first practice, while influences from contemporary art, music, film, and fashion punctuate his designs with exuberance.

From his Williamsburg home studio overlooking the East River, Nuriev delves into his formative years, his mission to create new experiences, and the relentless pace of the Instagram age.

What was your upbringing in Russia like? It seems to play an important role in your work.

I grew up in a very simple family, in a small city called Stavropol. My father is a handyman, my mother is a homemaker, and I have two younger sisters who both still live there. I have lots of warm memories from my childhood that I use in my work every day. The colors I use for example, come from my childhood.

What specific memories are the colors you use rooted in?

My grandmother's outfits. I was always around my grandmother, tugging on her skirt. She wore these funky mismatching colors. Some were super ugly, and others were bright and quite nice. Also, architecture. Russian architecture is very grey, but in small Russian villages super vivid shades of green and pink are popular. These vintage pictures of my childhood have become my references.

A lot of designers are focused on the future, but the past plays a big part into your practice. Why look back?

I think everything in life repeats. When we try to create something for the future, we're just lying to ourselves. Everything already exists. I'm focused on using my design language to transform my memories into a completely different reality and make them beautiful and timely.

For example, Demna Gvasalia [founding designer of Vetements and creative director of Balenciaga] uses a lot of memories from late-nineties Soviet clothing. It's close to my heart. I remember these outfits — leather jackets, chunky sneakers, and large sizes. These low-income looks were our everyday reality in Russia. The Russian aesthetic was asleep for years because no one cared about it. Now, it's a fresh way to talk about design.

What are you looking to for inspiration now?

Strangely enough the aesthetics of punk have become a strong reference lately. In the Soviet Union, it was forbidden. That's why I find it so sexy. I can really feel the freedom in the music and in the images of people in the subculture.

Your references are really stimulating. Is your design process just as dynamic?

I like to be alone in my workspace without talking or music. It's important for me to catch my gut feelings in the first three to five seconds of sketching. I try to stick to those initial ideas and not give up on them. My colleagues will try to turn down the first idea because they think it's too simple and want to think about it more. They'll go miles away from the first feeling and always come back. I don't waste my time on that.

So, you don't get caught up on anything?

If I'm really inspired by a specific material, it gets tricky. It can take my freedom away. All my ideas end up getting stuck on that material. Even if it's not working, I can't give it up. It's a game I like to play with myself.

How long will you give something before you abandon it?

We don't have that much time in this industry. So, usually a day, sometimes a week. I hate being on two designs at once. It's a disgusting feeling.

How does traveling between Moscow and New York impact your perspective?

It's really like traveling between two different worlds, Europe and America. But no matter where I go, I like seeing the dirty areas of a city. If I'm visiting somewhere new, I always ask friends to take me to a local market or a bar where their grandfather would go. I don't want to see fancy spaces. They look the same all over the world. I want to see real life.

And watch people interact with the environment they're in?

That's the most interesting part. It helps me create new experiences in my spaces. Do you remember the first time you held an iPhone in your hand? I'm trying to create new experiences like that, something that you've never had before.

I remember when the first, large multi-level store, like a Barneys, opened in Stavropol. Before that, there were just small shops. I was fifteen and I'd never experienced a store of that size before. It was a totally new idea. It's like the feeling you get when you visit another country for the first time, but on a smaller scale. I never forgot that feeling.

Do you try to recreate that feeling in your projects?

Yeah. For example, I recently completed a yoga center in Moscow. I've practiced yoga for ten years. Every studio I've been in, different as they are, has the same flavor. I wanted to do something new in a yoga space, so I referenced shaker houses. It's a weird reference, but they're super organized and clear, like your spirit is after practicing yoga. When people come into the studio for the first time, they're shocked that there's no Buddha or orange [walls].

Your work is about creating spaces that become long-lasting memories, but a lot of the press you've received fixates on the Instagram-able nature of your work. Does that bother you?

I do want to create spaces that make people curious and get their eyes off their phones, but Instagram is the new TV. In a way, it's become even bigger than TV. You can't ignore that fact. The way I see it, Instagram is a pretty great tool for becoming successful today. Only someone super successful like Angelina Jolie can afford to not be on Instagram.

Keeping up in the Instagram-era requires a constant churn.

It's a lot. My team and I are usually doing twenty to thirty projects at the same time, interior design, pop-ups, art, and exhibitions. We're also currently working on our first fashion collection. It's not just t-shirts, it's a more substantial, unisex line.

Does it ever get overwhelming?

Honestly, by May I had already closed my 15th show of the year. Usually, designers do three max. On top of that, I have my day-to-day practice to deal with. I'm human, so I felt empty. I needed a week or two to recover, but I couldn't just disappear. I've chosen this life for myself, so I have nothing to complain about.

How do you re-energize?

The best thing I can do is return to the basics — go to job sites, speak with my contractors, play with materials, and be present without any ambitious plans for tomorrow. And eat plenty of ice cream, of course.

Photography by Ben Hassett

Styling by Mia Solkin

Grooming by Abraham Sprinkle

Digital Tech: Carlo Barreto

1st Photo Assistant: Roeg Cohen

2nd Photo Assistants: Eric Hobbs and Chris Moore