Art

UPDATED: Open Letter Calls for Racially Insensitive Painting to be Removed from the Whitney Museum

Trey Taylor

21 March 2017

Update, 3/23/17:

This morning, a purported letter calling for the removal of the painting from the artist Dana Schutz herself made the rounds on the web. Whitney reps have confirmed to PAPER that the letter was indeed a hoax. Schutz did speak with artnet about the controversy, though, saying, "The anger surrounding this painting is real and I understand that. It's a problematic painting and I knew that getting into it. I do think that it is better to try to engage something extremely uncomfortable, maybe impossible, and fail, than to not respond at all."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

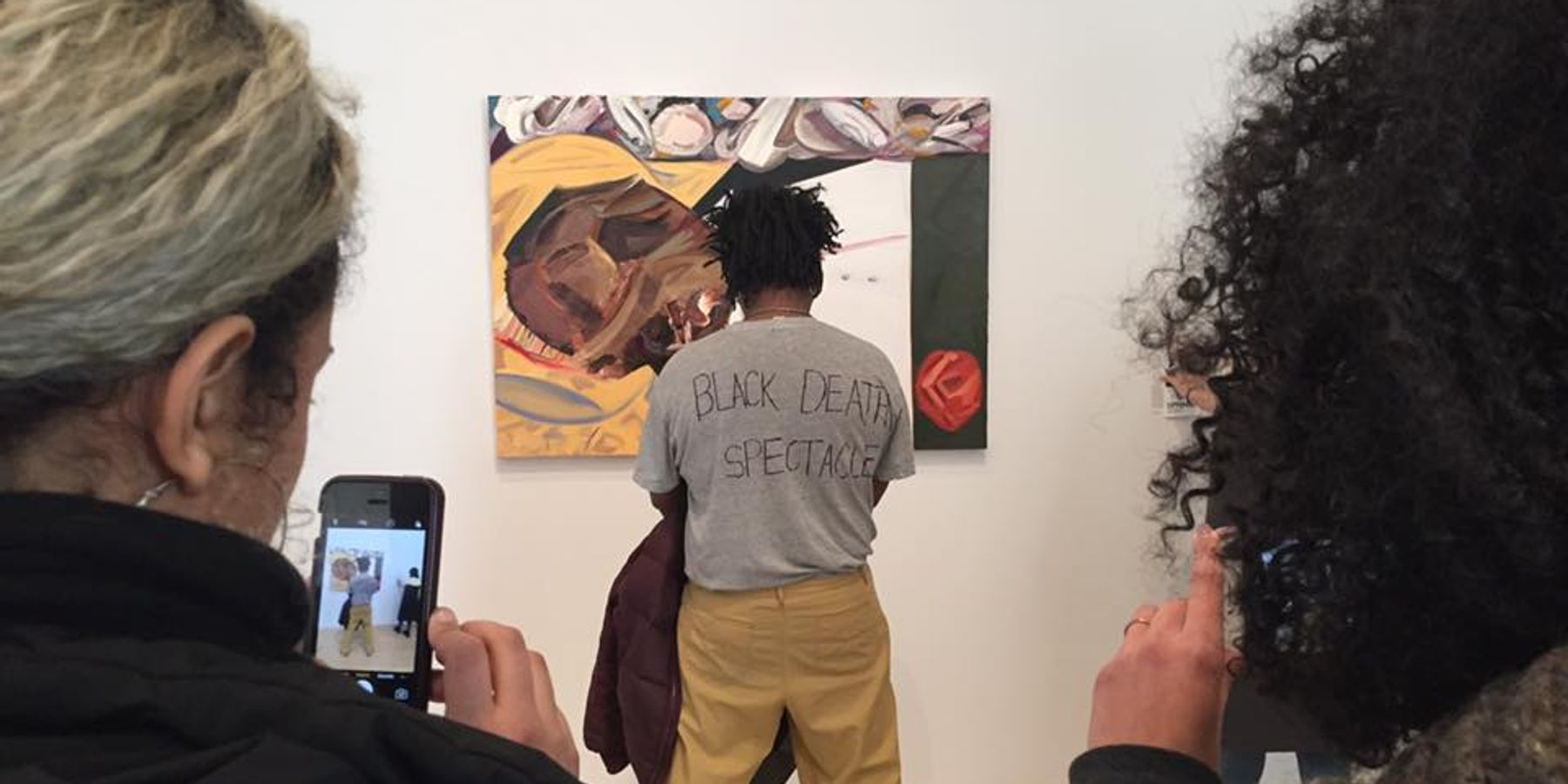

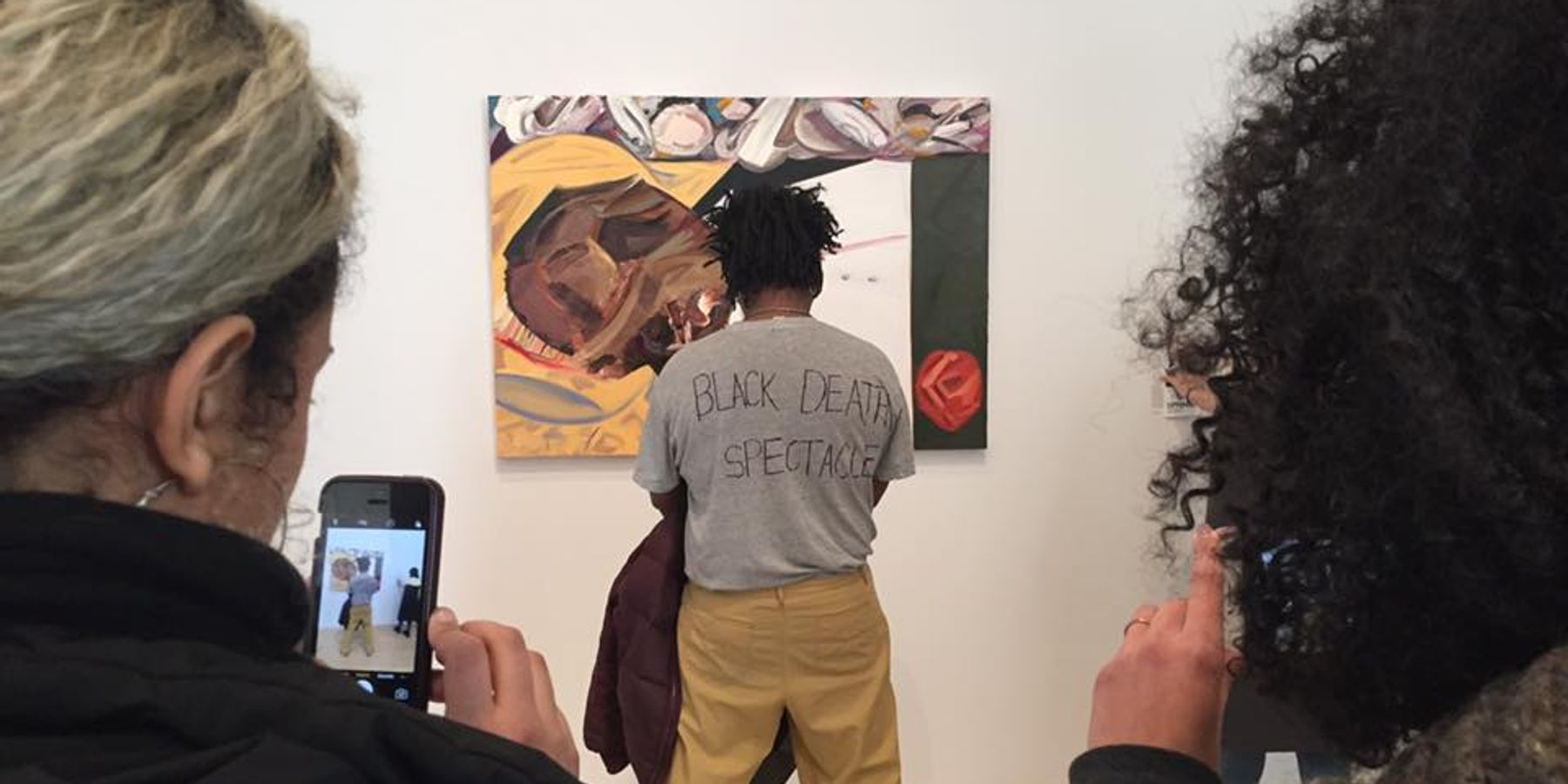

A painting depicting the mutilated corpse of black teen Emmett Till, on display at the Whitney Museum of American Art as part of the Whitney Biennial, has swiftly become the focus of protests and an open letter demanding it not only be removed, but destroyed entirely.

The painting, Open Casket by Dana Schutz, is an interpretation of a photo of the 14-year-old boy, who was lynched in 1955 for allegedly flirting with a white woman. Many in the black art community are outraged that Schutz—a white artist—is profiting off of a black murder.

It's only been up since Friday as part of the Biennial, themed “Violence," but has already become the target of an open letter started by artist and writer Hannah Black. “That even the disfigured corpse of a child was not sufficient to move the white gaze from its habitual cold calculation is evident daily and in a myriad of ways, not least the fact that this painting exists at all," the letter reads. “In brief: the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time."

The letter continues, “The subject matter is not Schutz's; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go."

It has already racked up over two dozen signatures from fellow artists, including artist Emmanuel Olunkwa.

“My heart is heavy, not because of Dana Schutz's painting but because of what it symbolizes, how it has been received, and how it has been accepted as a valid critique by the very system that is responsible for Emmett Till's death," Olunkwa says.

“Racism thrives on abstraction—that continuous act of moving the line of interpretation of critique when it is convenient for the artist or the market. Schutz's piece perpetuates what it actively seeks to critique. In short, the existence of the piece shows that blackness and black people can only exist at the hands of its oppressors."

Olunkwa continues, “History only exists and continues to be produced in an effort to exclude a certain class or body of people. Those in positions of power or privilege actively try to critique a movement or a people that are marginalized and have little to no autonomy over their body whatsoever. Schutz's painting fetishizes black death and normalizes the violence that black people experience daily. When someone who is wrongfully murdered, whose death is captured on video and then spread virally, whose body risks losing its meaning, a certain numbness is created that we have to be sensitive to and be wary of. Blackness has always existed at the hands of whiteness and while this binary at times seems inescapable, we can reject this false economy of critique that is violent."

The open letter's sentiments are also reflected on Twitter, where people are responding to the controversy:

Burn that #DanaSchutz painting of Emmet Till's open casket. White woman profiting off of black murder caused by a white woman #wow pic.twitter.com/7o5XqSmQ14

— 🌸HARD•TWEE🌸 (@RAF_i_A) March 16, 2017

Curious what #DanaSchutz, rich white painter, will do with the sale$ of her open casket Emmett Till painting...

— cathy park hong (@cathyparkhong) March 17, 2017

In a statement to The Guardian, Schutz has defended her position to create the artwork. “I don't know what it is like to be black in America, but I do know what it is like to be a mother. Emmett was Mamie Till's only son," she wrote. “The thought of anything happening to your child is beyond comprehension. It is easy for artists to self-censor, to convince yourself to not make something before you even try. There were many reasons why I could not, should not, make this painting … (but) art can be a space for empathy, a vehicle for connection."

The curators of the Biennial, Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, have also replied, telling artnet News, “For many African Americans in particular, this image has tremendous emotional resonance. By exhibiting the painting we wanted to acknowledge the importance of this extremely consequential and solemn image in American and African American history and the history of race relations in this country. As curators of this exhibition we believe in providing a museum platform for artists to explore these critical issues."

Splash image via @hei_scott