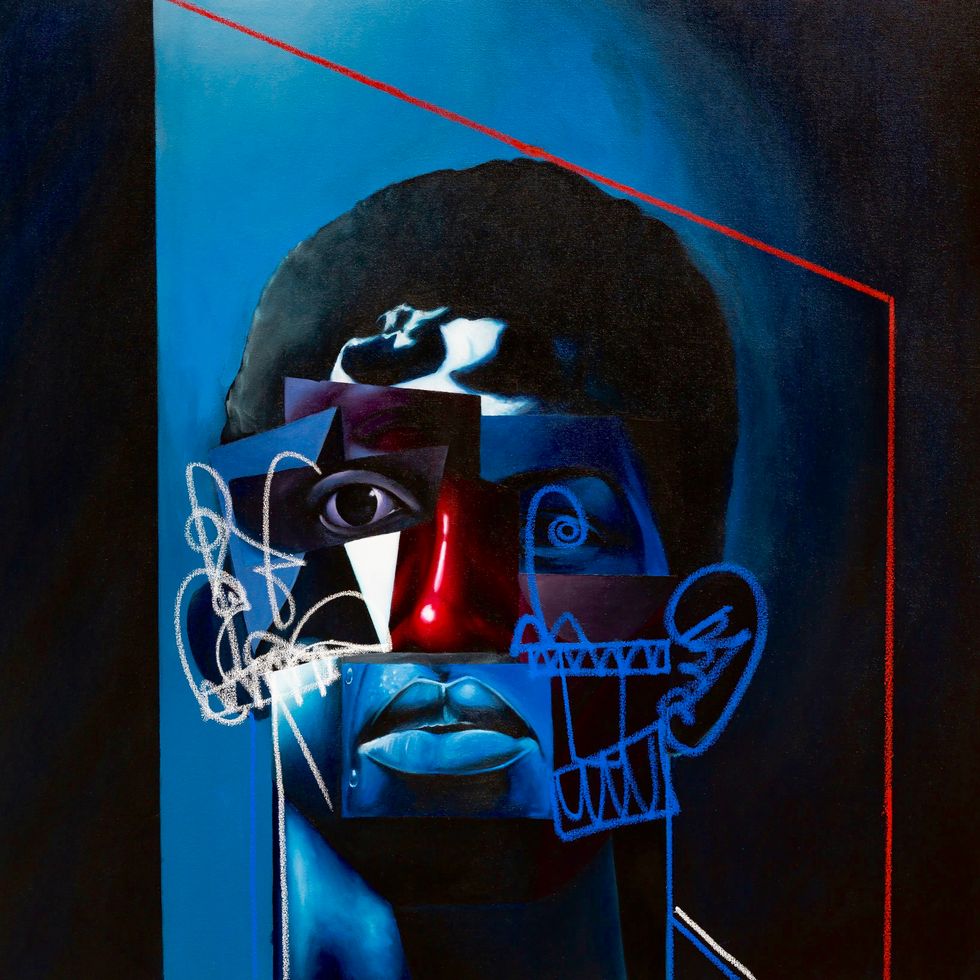

27-year-old Brooklyn native and artist Malik Roberts, is in his Blue Period.

To showcase this, on September 27, ABXY, the Lower East Side gallery founded and operated by Allison Barker, will present Blk & Blue, a solo exhibition of paintings, sculpture, and creative new media by Roberts. Roberts' show Stolen was last year at the gallery, and it shone a glaring light on the ills inherent of contemporary media's appropriation of Black culture. Blk & Blue is similarly, searingly honest, in its aim to dive into mental illness in communities of color, specifically in the Black community.

Roberts culled inspiration from Pablo Picasso's mental state and middle-class angst depicted during his iconic Blue Period — as well as his own (and his community's) experiences as a young Black man in America navigating the everyday tensions of systemic oppression and institutional racism. In doing so, the moody portrait and landscape paintings comprising Blk & Blue examine the conditions responsible for said hardship affecting Black and brown people, and illuminate the mental health consequences made manifest by generational trauma, including PTSD, anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder. And like Picasso, Roberts felt called to explore these themes using shades of blue and grey, with symbolic splashes of color.

Additionally, there is a multimedia component of the show, which enables viewers to unmask deeper truths that the naked eye can't readily see. As such, viewers will be invited to hold the gallery's iPad up to the paintings and reveal Roberts' "interpretation of the untold histories, undrawn borders, and invisible shackles" upholding racist structures in today's America, according to a press release promoting the exhibition. It is from this vantage point that the inner world of Roberts' subjects — ranging from a despairing mother to a murder victim — will be made undeniably clear, leaping from the canvas and into the soul of the viewer.

PAPER visited rising star Roberts as he was preparing the show. He walked me through the gallery and elaborated on the powerful themes present in Blk & Blue, navigating the ebb and flow of depression, and making an impact as a young Black artist. Read on for our interview, and get a first look of what you can expect come September 27.

Blue For Many Reasons, 2018

Is there a particular reason why this has been more on your mind?

My last show, I went more with icons. For this one, I wanted to go with the overall topic of mental health, and not focus on any one certain individual. That's why you can't point out a celebrity face or anything. I feel the conversation that has been bubbling and is getting closer and closer to the point where we can have an open dialogue about what's going on.

Are there any of your own experience that relate to this show? How do you connect to each of these pieces?

Each of these pieces represents people I've seen and known over time. Some are people in my family; people I've seen on my block; people telling me stories about when they were younger and why they had to do what they had to do. I also wanted to highlight what happens when you sit down and have a conversation with people when there is no one around — you'll find the toughest people will break and be like, "bro, I can't be dealin' with this shit by my damn self," you know what I mean? Those kinds of conversations I've had with people one-on-one are the ones I pull from. I'm really trying to tell their story in a way that honors them, something they can see themselves in.

What can you tell me about how you used light, or lack thereof, to frame these subjects?

I wanted to play with the shadows. When I was looking at Picasso, Caravaggio and Renaissance works, I adopted a lot of emotional and strong imagery. In much of what I looked at, light was really playing off the bodies, shadows hiding what maybe the subject didn't want seen. That was compelling to me, and I wanted to try that in these works.

I like the idea of collaging all of these people, stories, and ideas together under one theme.

That's where I started when I was creating this body of work - taking little aspects of things that I've seen and heard to make it into one, to tell the full story that I am trying to get across. That's why you see different styles. You might see a mixture of charcoal or a mixture of paint, but it's all just to tell different sides of the same story.

Who are your main inspirations, artistically?

Caravaggio, as I mentioned before, but this w hole series is based on and inspired by Picasso's Blue Period, it's like my version of it. I was always a fan of that era. It took time for me to find a story that fits and to be actually able to tell that and use those colors. Also, some work by Francis Bacon and a little bit of George Condo moved me as well.

It Couldn't Be Unseen, 2018

Tell me more about the one with the tears forming.

Yeah, you got to see the other side of Black men. I still think that there is this unfortunate thing where people always are looking for ways to take away from the full human experience that Black people are having. There is always this idea that you have to be so tough. You have to see that everyone is not a statue and sometimes they break and some pieces of the statue are breaking off. Everyone is human, from Black women to Black men.

Have you been depressed recently?

I get depressed every once in a while. I just know how I feel sometimes. After my last show, I was depressed for a couple of weeks and locked myself in my room for a little bit.

What do you think caused that after the show?

There's always a lot of build-up and excitement leading up to a show. You put yourself out there knowing people will all interpret what you have to say differently. It's exciting, but it's also a lot, and there was this crash afterward. That's definitely what happened. That was my first solo show and you're telling everyone and they're all so excited about it, and you like don't feel the same about it. Like, I know it's great, but ugh.

How long ago was it from when you started working on your last show to now?

My last show was in November. The idea started in December and as the conversation started building around it, I was like OK, I'm definitely going to take this route. So, about the start of summertime is when I feel like I really started drawing some sketches and coming up with ideas, and building a cohesive story line.

How do you feel about being a young artist trying to make it in this world?

I feel great. I feel like it's a good time to be alive and be an artist in this world. Especially as a young Black artist — a news piece came out recently about Wall Street buying up Black art. There are a lot more opportunities being created now for Black artists to thrive in. People are really looking to Black art across all type of mediums...I now have friends who are artists, so it's kinda cool to go to their shows and their galleries and then they come to my galleries. We all support each other, and that's a good feeling. That said, I am lucky enough to have been given opportunities, but I haven't taken them for granted, and I've killed it. I have. It's about working smart.

Woman by the Window, 2018

Your last show, despite the serious subject matter, used much brighter colors, so this is an interesting shift.

I am taking my work very seriously, I want my work to be as serious as I am. But for some reason my work ends up always being serious. My last show was about cultural appropriation, so this one is just another important topic of conversation. That's why I even changed the color palette, even though I loved the palette, I thought it was too bubblegum. I wanted to pull it back a little bit. I wanted to challenge myself. When I started the work that would become this show, I was doing straight greyscale, but it's hard to do grey against grey against grey. That was really the practice for me, to turn to the bluer hues.

How did that last show come together?

I start to get bombarded by the same stuff over and over. I'd see Kim Kardashian with braids, which she has since called "Bo Derek braids" and I thought, that started here [in the Black community]. Or I'd see a white girl getting a million dollars for twerking, but then I'd think what about the twerk team? It started to seem that everyone was getting credit for shit that I know we did. And I was like oh I have to do something so, I ended up doing the show that ultimately became Stolen. I was seeing too much of this, and it was really starting to get on my nerves. I had an argument with some white woman who said in all seriousness that Debbie Harry was the first rapper or some shit. Not true. Obviously.

Photography: Erik Bardin

Art courtesy of Malik Roberts / ABXY