Kenshi Yonezu sometimes seems like an idea before anything else. So much rests in the weight of his name that it's almost impossible to escape his orbit. The words "biggest artist in Japan" are often thrown around in his context; the video for his song "Lemon" is the most viewed Japanese music video in history. "Lemon" scored "Song of the Year" on Billboard Japan for two years straight, and if you passed through the virtual vestibules of Japanese music in 2019 (or really, any public place in Japan would have done) you heard his rendition of "Paprika," part of the 2020 Olympics social campaign. The concept of Kenshi Yonezu stretches wide, manifesting in eager nods of recognition or hums of familiarity with his name.

How this idea grew is equally fascinating, since Yonezu's career is divided into roughly two phases. The Tokushima native first gained traction in the late 2000s as a Vocaloid producer on the Japanese website Nico Nico Douga, working under the name Hachi. He released two self-produced albums, but found his field of view restricted in the increasingly isolated Vocaloid world. Shortly after, he joined the independent label Balloom, which was followed by the release of his debut album, Diorama, under his own name. Diorama's success led to Yonezu being picked up by Universal Sigma, marking his transition into the mainstream.

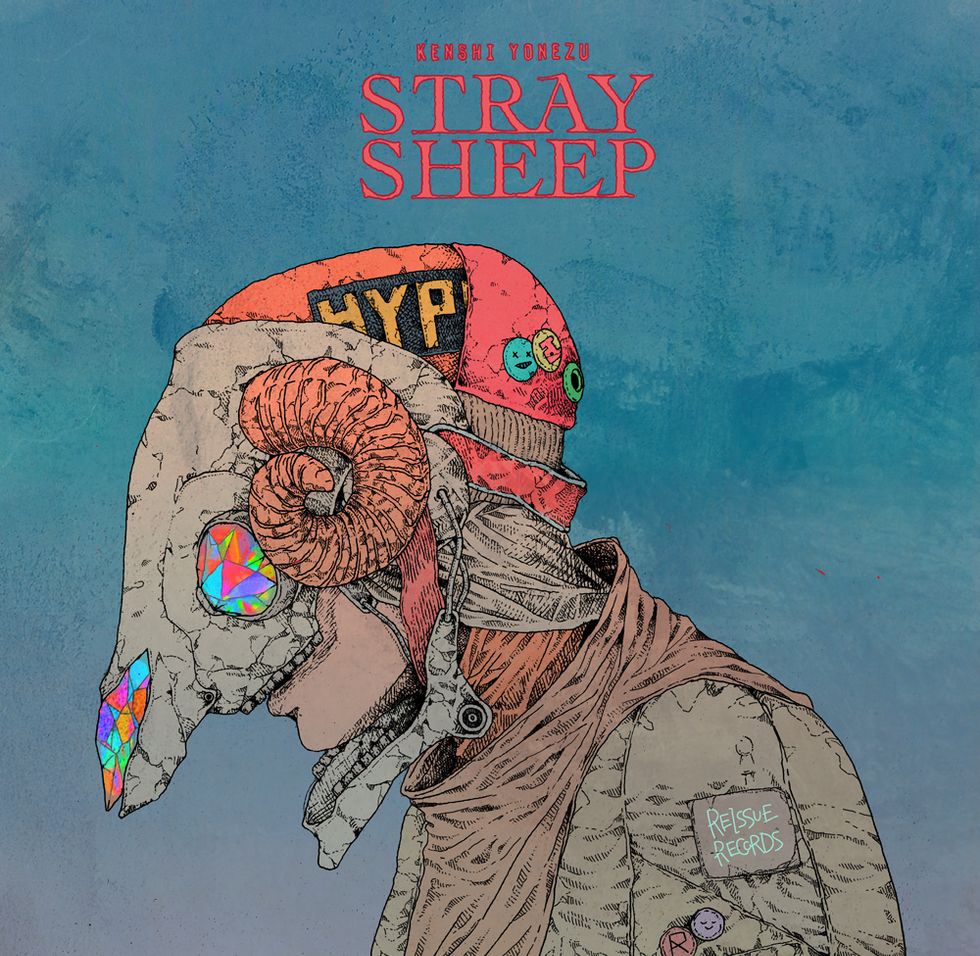

Yonezu's fifth and latest studio album, STRAY SHEEP, can be thought of as the endgame to this metamorphosis, something that he says has been three years in the making, ever since the release of fourth LP Bootleg.

"Initially, I didn't intend to call this album STRAY SHEEP," he says, speaking in a measured cadence peppered with thoughtful pauses and careful musings. "My initial intent was to create almost a story of what I've been through and my experiences, and turn that into an album. But then COVID blew up. Facing all this turmoil, I felt that I couldn't just ignore all that was happening and create music, totally distancing myself from the problems of the world at the moment."

That moment coincided with the creation of the track "Stray Sheep," a physical manifestation of how he was feeling.

"There were moments where I felt this incredible rage, incredible sadness — all these negative feelings," he recalls. "And it's easy to be a slave to those negative feelings and let yourself give in to those energies." But ultimately, he stresses, "I want to create pop songs. It was important for me to use the platform that I have achieved to send out more positive messages. I felt like that was my responsibility."

STRAY SHEEP doesn't feel optimistic at first. Loss and regret eat away at the soul on "Campanella," inspired by the character in Japanese author Kenji Miyazawa's Night On The Galactic Railroad, the pain of whose tragic ending is alleviated only by the reader's knowledge of his ascent to the "true heaven," where he believed his mother was waiting for him. On "Kanden," Yonezu teases a vast expanse of possibilities, only to put them just out of reach. Jealousy rears its head on "Yasashii Hito," reminding you of the ugliness of the moments you revel in schadenfreude. Even the cheerful, funk-leaning "Placebo" — a collaboration with Yonezu's longtime favorite, RADWIMPS' Yojiro Noda — leaves a sour taste in your mouth because of the dolorous possibility that everything good might be an illusion.

Under Yonezu's purposeful vision, however, STRAY SHEEP inverts. As he chips away at these emotions under various lenses — literary sources, his pop culture favorites, science-fiction reference points, and his personal emotional landscape — the excess falls away to reveal lucid pockets of light. It's akin to carving crystals, which are a "pillar to the album" and are peppered all over the artwork Yonezu did himself.

In an interview with the Japanese website Natalie earlier this year, Yonezu drew parallels between human development and crystals, saying: "Gems are born by happenstance as rocks, dug out by human hands, then polished and cut and such to achieve a beautiful form. I think that could be called 'damaging the raw ore.' The act of preparing it to look beautiful is essentially 'wounding' it… Similarly, at the moment of their birth, humans are like perfect spheres, which then get scratched and chipped by their home environment, friends, and other outside stimuli."

These abrasions and alternations litter STRAY SHEEP. In "Kanden," he fills the chasm of rudderless mundanity with the promise of eternity: "I'm sure there's eternity somewhere." On "Campanella," Yonezu turns remembrance into purpose, "devoting oneself more to the other than taking care of your own self," as he describes it during our conversation. In the eponymous "Stray Sheep", selfless love becomes the anchor point in a sea of losing yourself: "In the future, a 1000 years from now, we are not alive/ Friend, no matter what day it is, know that I love you."

Complementing these metaphorical crystals are the literal ones on STRAY SHEEP's artwork. Yonezu's's been illustrating most of his music videos since his Vocaloid days on Nico Nico Douga. Just as the purpose of a piece is to complete the bigger picture, so is a Kenshi Yonezu music video an extension of the ethos du jour.

Related | Break the Internet: BTS

"It's not really a conscious act," he explains. "After creating the songs, I just start drawing. Not with any real intent, but just listening to music and then just letting my hand create instead of my mind."

The artwork for STRAY SHEEP — which eventually was made available worldwide through a collaboration with UNIQLO — is just a little bit more special.

"It was almost like a culmination of what I have been doing so far, and kind of remaking a little bit of what I have done in the past. It was like a reintroduction of myself. 'Yes, this is Kenshi Yonezu,' so to speak, through the six designs," he explains, and in the same breath laughs and admits that he still hasn't wrapped his head around the fact his creations are splashed across people's clothes.

"[In Japan] Everybody knows about [UNIQLO]. That's something very unique, actually: to be something that everybody knows about and everybody accepts as being part of ordinary life," he marvels. "Now that I have come to the place I am right now, I realize that being ordinary and being accepted by everybody is a very difficult thing to do and quite similar to making pop songs as well in a sense."

If there is any quandary in being him, it's this. Yonezu sets a unique precedent in the modern J-pop landscape. Despite separating his career into two phases — his Vocaloid alter-ego Hachi and the music under his own name — his present work carries the fingerprints of the former, though it's certainly not derivative of it. Every work is him through and through, processed by the cogs of his mind and separated into musical and visual concepts, despite the mainstream big label tag.

"I am making Japanese pop music," he states. "Ultimately, that's what I have always wanted to do, that's what I have been striving for ever since I [debuted]. It's what I have always been thinking about. There's so many different types of music, such varieties of sounds. That's what makes pop music what it is, because it's so broad."

Yonezu's position is representative of a delicate reconciliation between "two conflicting ideas": creative control and mainstream assimilation. In the course of his career, for example, some of his biggest hits have stemmed from collaborations with popular art and culture entities. From "Orion," which became the ending to the anime March Comes In Like A Lion; to "Peace Sign," the first opening song of the mega-hit My Hero Academia; to "Lemon," theme song for the drama series Unnatural; to his most recent earworm "Paprika," which he produced for the Japanese broadcasting network NHK.

Despite the roster of third parties, the Kenshi Yonezu zeitgeist stays intact. No one song is removed from his influence, his touch almost tangible on every creation. Of course, this also brings up the necessity of this painstaking process. With resources that could just as easily paint his vision on mediums he wanted in real time, why the grassroots involvement?

Related | 12 Latinx Artists to Stream Right Now

"There's always the type of pop music that everybody is always listening to, that everybody is so familiar with. So, that's the type of music that I have been striving to create. I am always thinking about how to create such kind of music," he explains, but then adds that this creativity needs to be "a bit more fluid." When there are two conflicting ideas, he says, "I want to stand in the middle. There's always the possibility of pop music becoming more violent. I want to be at the exact point, the precipice where it's not too violent."

It's a delicate balance: " I don't want to create music that's for the masses and play it safe either," he counters. "Being in the position where I am now… I realize the position that I have been taking, my views on creating music probably aren't wrong."

Photos courtesy of Kenshi Yonezu