Music

Loners Can Be Lovers: Kali Uchis Talks Activism and Autonomy

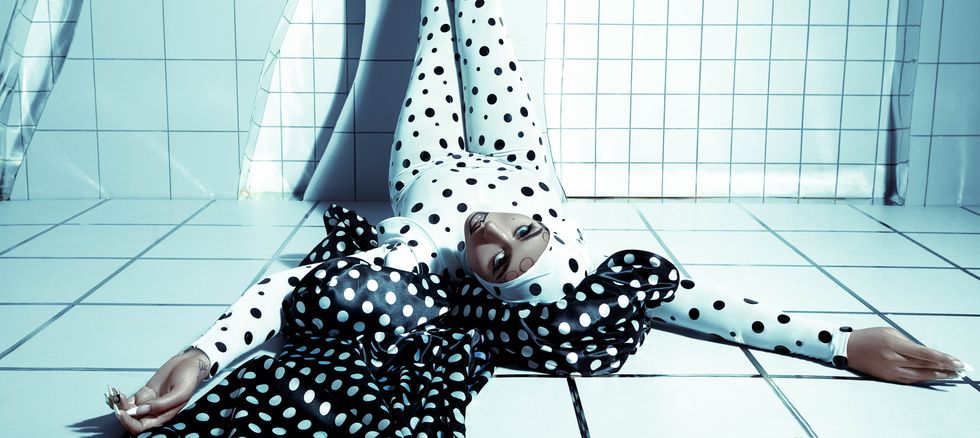

Story by Jhoni Jackson / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Rafael Linares

23 July 2020

"Even since I was little I've always wanted to view myself as a woman that is self-sufficient — that can stand on my own," says Kali Uchis, who just turned 26. She's young, and she has so much about herself and the world already figured out. Environment and her own nature brought an early coming-of-age for the Colombian-American; it's when she realized she was a certain kind of loner.

The subject is broached because the moment we're living through now calls for solidarity en masse. Does that not contradict the loner lifestyle? A predilection toward solitude, she explains, does not necessarily preclude a person from caring immensely about the well-being of others.

"It's more about being independent romantically and being independent spiritually," she says. "You can not have attachment — to anybody — but you can still want fairness for all people."

So as to not detract from the anti-racism uprisings in the U.S. and the overall spiked energy of the Black Lives Matter movement of the past few months, Uchis postponed the rollout of her sophomore studio album. Rather than use her platform on socials to promote new music, she's mostly posting and Tweeting about issues around social justice.

In April, Kali released TO FEEL ALIVE, an EP of reworked older material and a couple new songs, all falling in line with her typical Motown-tinged and reggae-underpinned style, as a way to tide fans over until the timing is right for the full-length. (She tells PAPER she expects to release it by the end of the year.)

In a now-deleted Instagram post, Uchis described the TO FEEL ALIVE artwork, a very femme and opulent scene picturing two women in a sex act, as "the Isolation-era me eating the Por Vida-era of me's pussy." The image feels like a metaphor for the most intimate kind of self-reflection, of unrelenting autonomy.

"How can I give a damn when I don't give a fuck?" she asks on the title track, where vocals are everything, like the smoothest of spoken word performance against a minimal background that serves only to elevate the strength of the message. "Don't believe what I read," she continues. "Got my own mind to think. Guess I'm a misfit baby, they won't have all of me."

Uchis has for years now been conveying her forever-flying-solo personality; in fact, there are tracks dedicated entirely to the subject: "Loner," from her debut LP Por Vida, in which she remembers why she'd "rather be alone," is one.

It's true that Uchis adamantly prefers to be "Solita" — cue her December single with lines about dancing alone, plus a play on the enduring Spanish-language maxim, "mejor sola que mal acompañada," which translates roughly, in contemporary diction, to "better alone than with someone shitty."

Steadfast independence is a primary theme of her first full-length, Isolation, too — that much is obvious. "Dead to Me," for one, makes clear the supreme finality with which Uchis will eliminate someone from her life.

But none of this is evidence she lacks empathy for others. Loners can be lovers, too. "I'm very nurturing," she says. "I love to take care of people, but I also go in my shell and can be really shy and standoffish."

Sharing ways to support BLM, calling out police brutality and violence, and raising the topic of anti-Blackness, discrimination against indigenous peoples and systemic racism in Latinx cultures is, to Uchis, simply "using your platform correctly." It is also, however, a form of attempting to take care of others — of entire communities.

Uchis uses a term, "non-attachment personality," to describe herself. "I just kind of made it up," she says, but it turns out that nonattachment is actually a studied mental strategy for relinquishing the learned need for total control over life. Subsequently, this means stressing less and appreciating the present moment more.

In some ways, that aligns with her personal history; letting go also includes working to stop worrying about other people's perceptions and opinions — and Uchis has always been a disruptor, indifferent to what anyone has to say about it.

Recalling her childhood, she says, "Something didn't sit right with me about authority figures. I was the kid that was always pushing the buttons and asking the questions, whether that be when my mom tried to put me in bible study when I was little, or teachers at school. I was always pushing those boundaries and making people uncomfortable with the questions I had."

Issues within the public school system were too jarring for Uchis ignore. The food served at lunch wasn't healthy, for one, but she was especially affected by seeing firsthand that students with disabilities were treated as incapable of living full lives; the kids were made to do custodial work. When Uchis confronted a school official charged with these students, she was told they were being "prepared for the real world."

Not long after, she "went into a wormhole" studying what some might call conspiracy theories — government cover-ups and the like. She also schooled herself on Buddhism and other religions. Reading Siddhartha was formative. That kind of initiative to learn about the world, about history, about society, about people — it just doesn't feel like something an apathetic person would do. Uchis may choose to be alone, but she does truly give a shit.

For her, this is not activism, per se, but simply the right thing to do. "I do not consider myself an activist," she notes. "I've always had strong opinions about things that other artists might not feel comfortable speaking on, and so I feel that God gave me my voice, my platform and my empathy for a reason."

One particular track from TO FEEL ALIVE, "i want war (BUT I NEED PEACE)," resonates deeply right now, as so many people are fighting to reach the closest thing to peace that's possible: a just and equitable society for all.

The song is intimately personal, however — written in reflection of her own inner war that's related to past trauma. "When you're broken or you've had a fucked-up past, a lot of times you're prone to repeating those patterns, and you're prone to drawing toxic people into your life," she says. "It's a cycle. I was learning how to overcome the self-destructive parts of me to finally accept peace."

But she encourages interpretation of her songwriting, in that she hopes listeners will apply her lyrics "to themselves and their life however best they want to."

Uchis herself thinks critically and liberally — about everything. Freedom of thought is paramount. "When I see people that believe anything other people tell them, it really irks me," she says. "I'm like, 'Why are you doing that?' Look into it for yourself."

That's where being solita has its advantage — one aspect, anyway. The fortitude of self that Uchis developed through her commitment to autonomy has made it possible for her to be candid with herself, to assess and analyze, like in the past mistakes she says she's made.

After all, the ability to self-examine is absolutely necessary for people who want to be allies and accomplices to marginalized people.

For years Uchis has been speaking out for the rights of immigrants and undocumented people. She was at some of the early BLM protests in D.C. six years ago, 20 minutes outside her hometown in Alexandria, Virginia, where she still lived at the time.

Amplifying awareness of these causes is not the only purpose for which she's used her platform, of course — and there is absolutely nothing wrong with feeling-yourself selfies or other mood-boosting content. But Uchis points out she's made mistakes along the way and they've led her to continue to "learn to be better."

A few years back, Uchis created Fundación Visión, Valores, y Vida — Vision, Values, and Life Foundation — with the mission of creating safe spaces; at this point it's an initiative advocating for multiple causes.

In 2018, through her organization she teamed up with Puma to gift toys and clothes to kids in Colombia during the holiday season, and recently collaborated with No Us Without You to support undocumented service industry workers and their families amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Uchis started an Instagram for the foundation only recently, and has been sharing info on Latinx voting power, BLM, the disproportionate climb of COVID-19 in marginalized communities and the origins of Pride.

"That's what this whole movement is supposed to be about, for all of us to be able to recognize how we have benefitted from the system," she says. "Our closeness, our proximity to whiteness, is what we should be examining — how we've benefitted. How if I looked like my grandmother, who was indigenous, I probably wouldn't have had a lot of the opportunities that I've had, or if I were Black."

To be anti-racist as a non-Black person requires admitting your own role in an oppressive system. Not everyone is willing to do this; they're so worried about how others will perceive them, if someone will call them racist, if they'll be called out or canceled. And so they stay comfortable in their privilege, complicit in perpetuating a society that is unjust.

Her education in public school isn't what expanded her social consciousness, either. Experiences by proxy with the criminal justice system showed plainly to her its discriminatory discrepancies. Working in the service industry at one point, she noticed the exploitation of undocumented workers.

Environmental factors — add to aforementioned eye-opening milestones that, while Uchis was born in the U.S., her Colombian father for a time was undocumented — can boost a person's ability to see outside themselves. But that's not the case for everyone. (See: All the pro-Trump Latinx folks, for example.)

What got her to this place is that she's been adamant about self-learning; in her adolescent years she spent time studying Siddhartha and photography and videography and government corruption and cover-ups. As she hits her mid-20s, Kali's education continues; she is a lifelong autodidact.

"I didn't go to college, you know," she says. "There's so much information on the internet, and there's so many books in the world, and there's so many ways to educate yourself, which is what I've done."

For those with a massive audience, with super-wide reach — including non-Black Latinx artists who make their living through music originally created by Black people, like reggaeton or hip-hop or trap — there is no excuse for "the disappointing behavior." There are many, she says, who "should be using their voice and platforms better."

"I try to always keep in mind that my platform should be sacred," she says.

It is not some fluke that a loner like Uchis possesses so much empathy. Caring for others is not a personality trait, and it is not political activism, either — it's what you should do. And no matter the size, every single person has an important platform of their own.

Photography: Jora Frantzis

Styling: Rafael Linares

Fashion: Louis Verdad

Makeup: Josie Melano

Hair: Yalina Flores