How James Merry Made Björk's PAPER Cover Mask

By Joan Summers

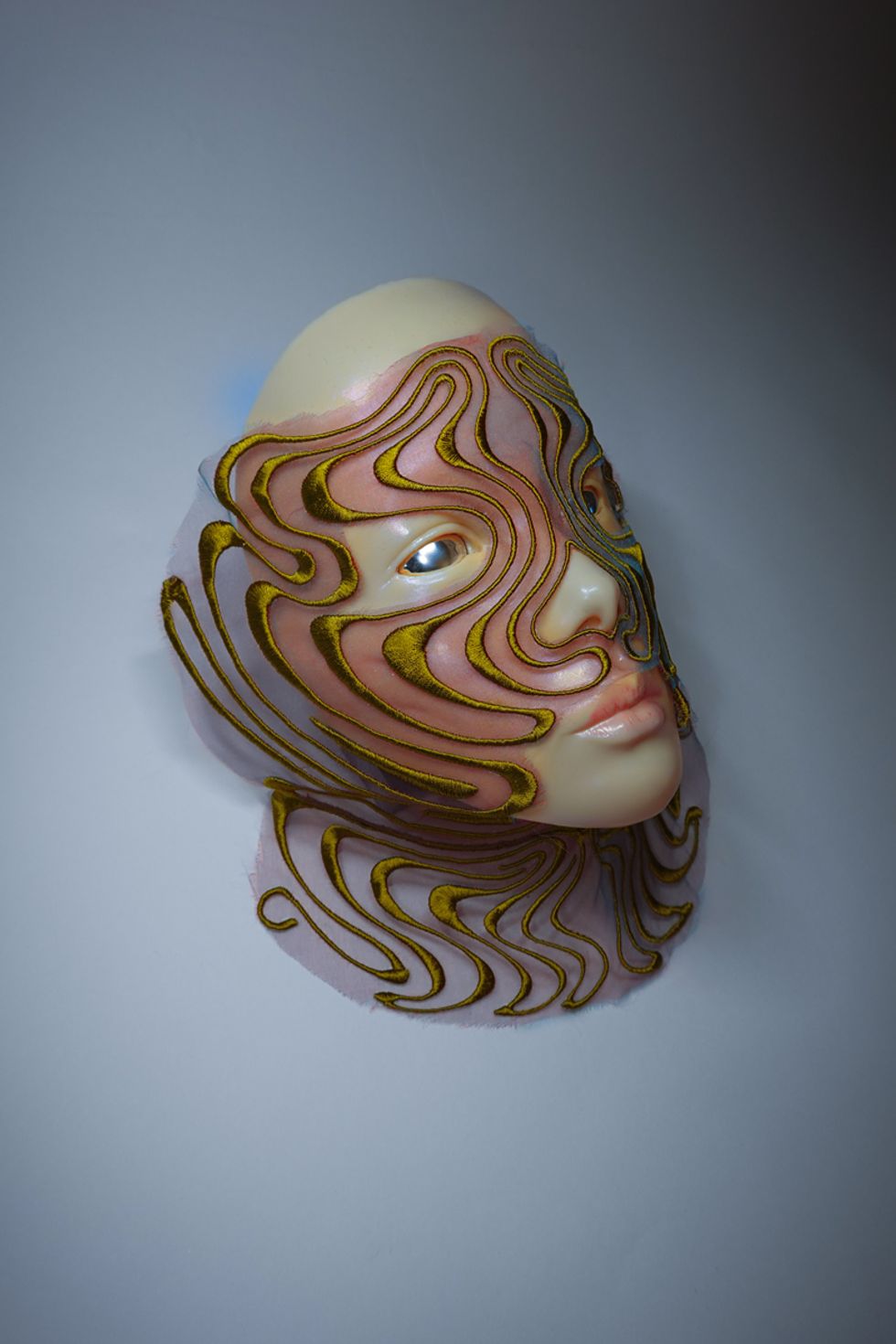

Jan 29, 2025Still thinking about PAPER’s cover story with Björk? Thank James Merry. The renowned artist and the pioneering musician’s co-creative director designed the “Blaschko mask” that she wore. Like many of the pioneering creations he’s made for her since hand sewing masks for the Vulnicura tour, he embroidered the “Blaschko mask” on iridescent gauze and then hand-stitched it together. As for the name, the mask actually finds inspiration in the natural biological function known as “Blaschko’s lines,” which Merry recently found himself fascinated by.

As Merry details in his process video below, Alfred Blaschko discovered that there are invisible lines and stripes across the human body that “trace embryonic cell migration as we develop.”

While sometimes visible through certain skin conditions, these otherwise unseen markings can cover the human body, and are originally detailed in Blaschko’s 1901 paper on the subject, published in German. “My German isn't great so it took a bit of searching, but luckily it was all digitized and easily accessible on the Internet Archive,” Merry tells PAPER. As for what he found there: “His diagrams are so beautiful and detailed. I studied them really closely to get a general sense of how the lines are placed around the body and what sort of contours they follow, before I started any sketching.”

Surprisingly, Merry also discovered that many of his previous masks actually trace these invisible lines, indicative of his innate artistic proclivities. He says of the realization: “That was a cool moment, when I looked at the lines on the face I could immediately see that many of my other masks already followed them. It's nice to know my instinct on form and shape around the head were actually following something tangible and scientific, hidden under the surface.”

For more on Merry’s process, Blaschko’s lines and work with Björk, read PAPER's full interview, below.

Blaschko's lines are a fascinating biological development, and also not something that many people know about. What got you interested in the human body in this way?

I got obsessed recently with stripy hair in animals, mostly because I was really fascinated by the markings on my cat and noticed that it wasn't simply patches of solid color, but the fact that each individual strand of hair was striped, caused by the Agouti gene. I wanted to find out if humans ever displayed the same sort of pigmentation in their hair, and while I was looking into that, I stumbled across the fact that humans do actually already have stripes in their skin!

Your work with Bjork often plays on her artistic relationship to the biological, human or plant or otherwise. Like with Blaschko's lines, do you find that having a deeper understanding of science and nature have become integral to your craft?

Yes, definitely. Most of my work usually begins with a fixation on something biological, usually anatomical, botanical or osteological. That’s often the starting point, but then I spend a lot of time developing it into some new shape or form, and eventually into a sort of character that can be worn on the face. That process takes a while, and I try not to force it. I just let the references swim around for months until it comes out instinctively while I'm working in my studio.

You tracked down the original 1901 paper by Alfred Blaschko. Talk me through how you tracked it down, where it was and how you landed on the final design from there.

My German isn't great so it took a bit of searching, but luckily it was all digitized and easily accessible on the Internet Archive. His diagrams are so beautiful and detailed. I studied them really closely to get a general sense of how the lines are placed around the body and what sort of contours they follow before I started any sketching. I didn't want to be too literal about it and just copy the lines as they are, so I spent a week or two just refining and working on the design until it felt like part of my visual world, but with an obvious nod to its scientific inspiration.

How did it feel, after reading the paper and seeing his diagrams, to discover that many of your previous masks also traced these invisible lines?

That was a cool moment. When I looked at the lines on the face, I could immediately see that many of my other masks already followed them, sometimes almost identically. It's not completely surprising. The lines follow the natural shape of the body as it grows, and my masks are often made to look like they are growing out of the face, so it's likely that those might overlap. But it's nice to know my instinct on form and shape around the head were actually following something tangible and scientific, hidden under the surface.

Your masks have ranged from intricate embroidery to metals and pearls and just about every material under the sun. You've really pushed the possibilities of masks beyond their limits! Through them all, though, do you feel there are important elements, or fundamentals, you think about when designing a mask?

I have recently been archiving and organizing a lot of my old masks, so it was quite interesting to spot common threads that show up amongst them. Obviously, there are exceptions, but I think in general, I am usually trying to make something that looks like it is growing out of the face or head, rather than something placed on it. All my metalwork pieces are made from one continuous piece of metal. I will spend weeks figuring out how to fold a design out of itself so it can be cut from one sheet. I realized that it feels more organic that way to me. When there is no joining or soldering involved, it feels like the shape could have grown naturally out of itself, like a bone or a flower. I often don't like to see how a mask is worn too obviously. I want them to float around the head in an uncanny way, so I think a lot of them have that similar feeling. But mostly I think all of them are about the contradiction between hiding and revealing — how much do you give away, what do you reveal, what character does it create — all at the same time.

Back at the very start of your mask making journey, what first drew you to them?

The whole mask thing was born out of necessity originally. Björk was getting ready to start touring the album Vulnicura, and was looking for some masks, so I started making them in the evening while I was watching TV — just a sort of very casual side project while I was busy during the day with all the other stuff. But then it slowly started snowballing, and as the tour travelled, I would try to make a new mask for each new show. It eventually became a much bigger part of our collaboration. Up until this point, I have deliberately stayed away from reading too much about the theory or history of mask-making, as I still wanted to keep it spontaneous and instinctive. But I think that might change soon. I feel ready to start looking back and understanding them a bit better, in a wider context. The next masks I am making this year will be more inspired by archaeology and my interest in that, so I have a feeling that I'm heading into a new phase, less about following some biological instinct and more into historical symbolism.

As you explore more about your interest in archaeology and the historical context of mask making, are there questions or particular themes or art and time periods that you're most interested in?

I am particularly interested in the later end of the Iron Age in Europe, specifically Britain in the period just before and after the Roman invasion (43 A.D.). I spent most of last year reading hundreds of academic journals and books about this period, especially related to regalia and headdresses found at temple sites. Lots of the objects surviving from this period, particularly a phase called La Tène, are my favorite artworks anywhere in the whole world. The next masks I make will reference this more explicitly, each one taking its inspiration from a specific archaeological site nearby where I grew up in the UK.

Photos courtesy of James Merry

From Your Site Articles

MORE ON PAPER

ICONOS: Pepe Aguilar, El Oficio del Tiempo, la Voz del Silencio y el Peso del Legado

Español

Jan 19, 2026

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October