Björk Is Hopeful for Our Planet

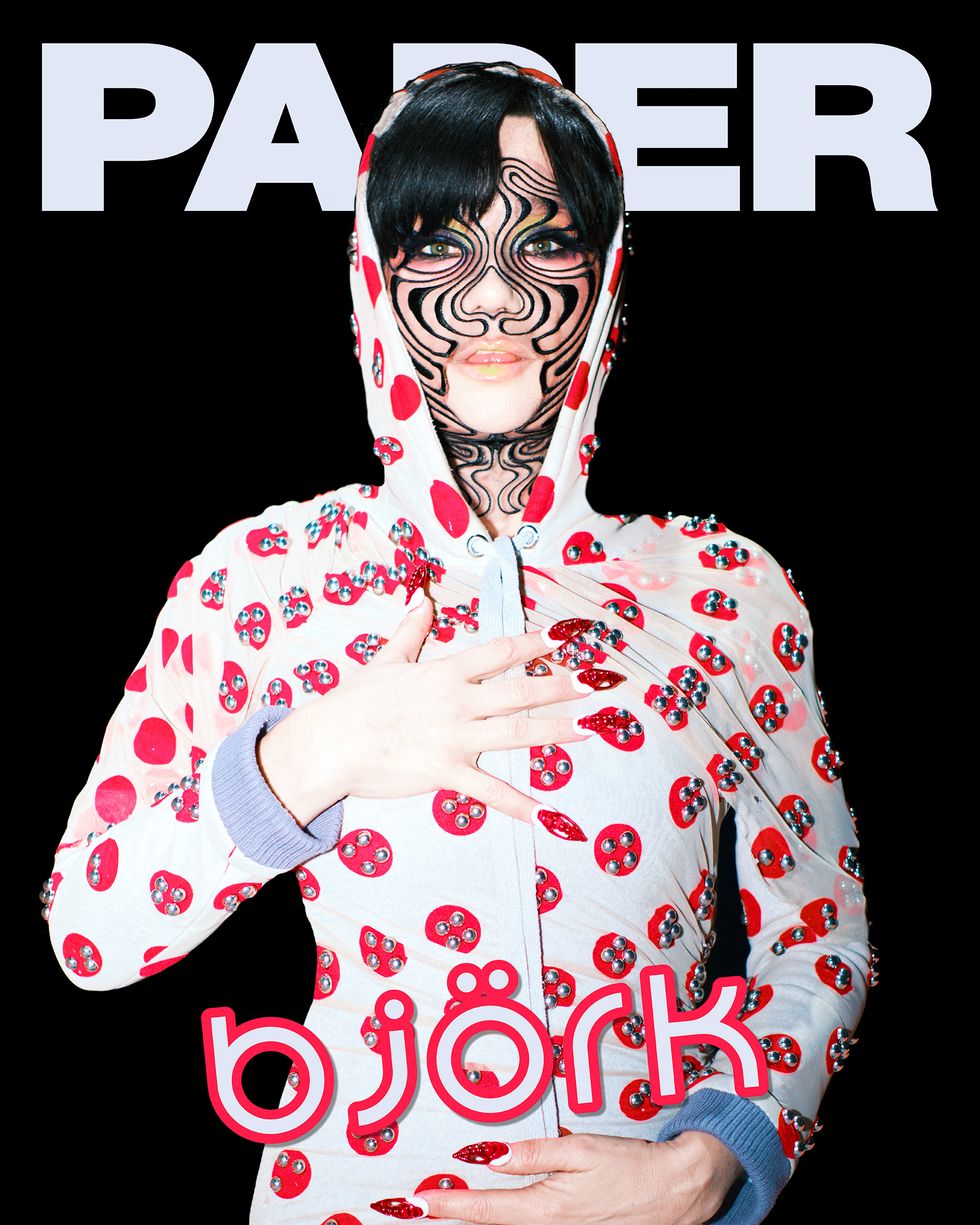

Story by Matt Wille / Photography by Vidar Logi / Styling by Edda Gudmundsdottir / Makeup by Daniel Sallstrom / Hair by Ali Pirzadeh / Nails by Texto Dallas / Set design by Andrew Lim Clarkson / Masks by James Merry

Björk is optimistic about our planet’s future. In the face of seemingly constant environmental disasters, her outlook goes against the public sentiment of many. “The nihilism, the self-pity, it’s like it’s cool to give up,” Björk says, a slight chuckle in her voice. “I don’t think it’s cool to give up.”

This optimism in the Icelandic artist’s worldview is stark and refreshing; it’s also integral to her work. Most recently, she completed the film version of Cornucopia (available for streaming January 24 on Apple TV), a four-year-long “digital theater” tour that made stops in four continents and totaled 45 shows. Originally premiering at New York City’s The Shed in May 2019, Cornucopia took a full two-year hiatus due to COVID-19 restrictions, eventually finishing in Bordeaux in December 2023.

Cornucopia is Björk’s first tour not named after a specific album: “I just knew it would be a vessel for more things,” she says. The show evolved over its tour; originally comprised mostly of songs from 2017’s Utopia, the 2022 release of Fossora (recorded during the show’s pandemic break) added a new layer to the setlist. Cornucopia is what Björk describes as a VR experience made for an IRL audience, an effect made possible by the inclusion of varying layered types of displays and gorgeous animations — ”an overload of screens and colors and celebrations,” as Björk puts it. This is in addition to bespoke instruments (a circular flute played by four people simultaneously, a xylosynth, a piezoelectric violin, organ pipes, an aluphone and a harp with steel strings), a custom cocoon-like reverb chamber, choirs and more.

Dress: Ella Douglas, Mask: James Merry

The show has a strong narrative arc that Björk succinctly describes as being “about healing.” It features a classic hero’s journey plotline that plays heavily into Cornucopia’s environmental messaging — an edict made explicit when a handwritten memo scrolls across the screen during the show. In it, Björk urges audiences to “carve intentionally into the future and demand space for hope.” Björk imagines this future by understanding that the apocalypse “has already happened” — so rather than looking to avoid it, we must pick up the pieces and imagine new futures for ourselves.

“Of course we are facing a very difficult situation. But I think we will overcome it, or for me, it’s more about taking it for what it is,” Björk says. “We have to write climate accords that we can reach. We have to keep tweaking it until we get it right. And I’m hoping the next generation, when they take over, they’ll think about it in a different way and come up with different solutions, green ways of living.”

This understanding allows Björk to feel hopeful about our collective future; that in the face of apparently overwhelming circumstances, we do have the ability to control our fate by building it ourselves.

“It’s about figuring out how we can keep humanity and soul in the future worlds we’re building, where nature and technology can collaborate,” she says. “But I think it is possible. I think with imagination, biology can take it, biology will be fine. Biology always wins.”

PAPER caught up with Björk just before the release of Apple Music Live: Björk (Cornucopia) to discuss the show’s inception, her many masks, the process of turning the tour into a film and, of course, environmental optimism.

“You can change the direction of the current from your heart to become generous again.”

Hello, thanks for taking the time to chat.

Of course, thank you for your interest.

You’ve been on the cover of PAPER a few times — two solo covers and the 20th Anniversary edition with John Waters, Chloë Sevigny, a bunch of other people.

That one was a lot of fun.

I’m excited to talk to you about Cornucopia and I’m curious about how the show started. What was the seed for the show?

I was doing a lot of work in 360 degrees, both sound and visuals. I did both Biophilia, which we were programming for apps — lots of prime numbers. Working on how a pendulum could be visible, but it’s also the bass line in the song. Arpeggios are thunder and lightning — just trying to break up music for myself into a more 3-D, spatial thing. Then the VR album we did for Vulnicura, we ended up working with seven teams and doing seven different VR videos. People were complaining at the time that VR was isolating, all alone with your headset — and I said, “Well, perfect, I just wrote a heartbreak album.” The emotional isolation I felt in Vulnicura matched that.

So I came out of that world, after mastering everything in 360 in the headset and the VR visuals. I was like okay, that was all fine and good, but you’re right, it is a very isolating experience to put on a headset. It’s not communal. And emotionally, I didn’t want to do another lonely album. I felt the opposite emotionally. I was writing very open, communal, celebratory music on Utopia.

So the birth of Cornucopia was about taking the 21st-century headset, taking it out of VR and putting it onto a 19th-century stage. So we did 27 screens that were open and closing, like an analog VR. And that’s why I called it “Cornucopia.” I always visualized it being like Times Square or Trafalgar Square, sort of like visuals! visuals! visuals!, an overload of screens and colors and celebrations. For example, the song “Arisen,” how we did it in the film and the concert, comes from that idea, that celebration of digital theater.

Digital bounty, really. How would you describe the overall narrative of Cornucopia?

I have some friends in Iceland who write novels. More of my friends are authors than musicians, and they ask me sometimes to read through the first draft of their books. And actually, by surprise, they found that I’m helpful in doing that. I’m rubbish with grammar and paragraphs, but I’m okay with structure. And that’s probably because I’ve been doing set lists and bands since I was 14. How you combine the songs, just by doing a different order with the same songs you can do two different shows, and it’s very exciting. So, I guess I’ve been exercising the muscle since I was a teenager.

But with Cornucopia, there are several versions of it, because we did it first straight after when the album came out, then we did it at The Shed, which was the next version, then COVID happened, and I went and wrote Fossora, and then I put Fossora tunes into it. So there have been several narratives going through the set, but I would have to say, overall, we kept the same skeleton. We start the show with “Family,” it’s almost a flashback, when you see those TV series that start with Previously... So that’s from Vulnicura. It’s how that character heals itself. And then “The Gate” starts. That’s the beginning of the show.

Another way to tell the story is to say it’s a collection of avatars. Because I did — sort of on purpose, sort of not on purpose — work with several directors to do a collection of avatars. We started with the avatars of “Notget” and “Family.” That “Family” character is broken, but heals itself, sews itself together and stands up. “The Gate” avatar is after trauma, when you have split your personality into all the different prime colors, you put them all together into one color and you’re healed. And your “gate” is your heart wound, but it’s not a wound inside you, instead the energy goes outwards. You can change the direction of the current from your heart to become generous again.

A lot of the avatars were done with Tobias Gremmler. I told him the color palette, the emotions, the plants, the sci-fi tale. And the whole sort of blooming after the horror of Vulnicura, erotic energies coming again. What I did with Tobias was go through each song literally frame by frame. We spent a lot of energy and time [on] emotional accuracy. I wanted there to be synesthesia, as much seamless merge between the emotion of the song and the emotion of the visual. Open and close and fast and slow, as much in sync with the music as possible.

It is basically about healing. That’s the short way to put it. And it does have an old-school story of a hero, where you start and there’s a problem, and then there’s a cathartic moment. First everything goes well, then there’s the battle of opposing forces, and then it’s overcome, and it ends in a peaceful, happy ending.

Mask: James Merry, Clothing: Kiko Kostadinov

I saw the show in 2019 at The Shed and I’m wondering what it became afterward. How would you say the show evolved over the years you’ve been touring it?

Of course, the first few shows always have some virgin energy. The first three shows were okay, but then the fourth show, everything just fell into place. We all looked at each other like wow, because it was bold to put together a seven-meter-long organ pipe, the circular flutes and the choir. It was sort of megalomania, but on purpose.

What happened later in the show, the songs became more like the length you would normally have in a concert. Not because they were boring or anything, but because I was thinking of the whole structure; it needed to be more streamlined. The amount of animation edits and shortening down the songs, it’s almost been like editing a film. It’s been a lot of work to get it down. So I did shorten some of the songs on the European tour in the autumn of 2019. Then we were away for two years for COVID, and when we came back in California, I shortened a couple more songs, and then we even shortened more songs, and when we added the Fossora tracks we actually skipped a couple of songs. It became even more streamlined.

In that sense there were certain things that improved. But, of course, it didn’t have that virgin energy of the first shows. It had a different kind of energy, and the flute players got better and better. They were phenomenal, because there was space for them to become themselves more. They could make it theirs. There was room for their characters. You could really get the individuals. When I was editing the film, you could see just how much the flute players were giving. You could see the close-ups on the film — that had really grown. And, lyrically, I was fine-tuning things right to the end.

Photo courtesy of Santiago Felipe

How did the Fossora process interact with Cornucopia? Were you working on them simultaneously?

It’s the first time the name of my tour is not the name of an album. I knew it would be a vessel for more things, I just didn’t know what. Nobody had done that before, to have that many screens and those sort of instruments and travel with it. I told my manager before I did this, “Listen, I’m going to do digital theater, it’s going to be megalomaniac, it’s going to be the first and last time I do this in this way.”

Then COVID came, and I was very happy to get two years in my home, not having to take one airplane. Iceland wasn’t really affected by COVID, there weren’t many restrictions. So it was a very happy time to be home and get all my belongings from New York. For the first time since my early twenties, I had all my belongings in one place. So for my next album I just wrote from that point of view.

When the restrictions were lifted, I was like, “Okay, this can be a vessel for two albums,” and I added some of the songs in but still with the same narrative curve as Utopia. There are overlaps — it’s all plant-themed and you also have a binary element there. Utopia is obviously utopian, a fantasy, Fossora is more the reality, more earthy, it’s grounding; Utopia is the sky, Fossora the element earth. We put bass clarinets in a sort of hole on stage. It was almost like the world below the city in the sky.

Dress: Ella Douglas, Mask: James Merry

Masks play a large role in Cornucopia’s aesthetics. Can you talk more about the masks?

I’ve worked a long time with James Merry, he’s one of my closest collaborators. I call him my co-creative visual director [laughs], which sounds insane, but basically when it comes to the music, I’m boss, but when it comes to the visuals, we do it together. The way we work together often is I get the broad ideas — for Utopia it’s flutes becoming synthesizers, plants becoming humans, it’s mutant energy, so I say, “Can we create mutant energy?”

James learned very quickly in a hotel in LA — he’s very DIY and made silicon pieces for my face where I was changing into flowers and orchids. Erotic undertones, and also the sense of the grotesque, because of the sci-fi elements in it, the environmental tale.

But [the masks] all have different stories. I got obsessed with golden floral jewelry, so I showed that to him and he started making masks inspired by a golden botanical world. After the emotional violence of Vulnicura, which was barren, very winter, minimalistic, grief, we wanted plenty. We wanted paradise. We wanted this post-apocalyptic story. Well, I actually call it “post-optimistic,” because the apocalypse has happened and we’re gonna be fine. We will lose a lot of species, we will have radiation issues, and all this global warming fucked-up-ness, but biology can handle it, and we will be maybe mutants with plants and toxic things, but it’s about survival. The lyrics of Utopia are about escaping the violence of a self-destructive civilization and going to a tropical island, and starting anew with the women and the children. And you break branches and create flutes.

Me and James, we talked a lot about that. We were living in the same building, so we would have meals together. James is literally like family. It was very seamless. And the masks came out of that, for myself and for the flutists. When it came to Fossora it was more earth, more mushrooms and he started casting his masks in real silver — more earthy and real.

It’s been one of the most wonderful journeys I’ve had. I’m blessed, even though we don’t live in the same house anymore. We still finish each other’s sentences.

Photo courtesy of Santiago Felipe

The Cornucopia film brings the show’s visuals to the forefront, even overlaying you and the band. What was the motivation behind that particular choice for the film?

I put so much work into the animation, I guess technically I would be called an “animation curator.” [Laughs] And then on stage, we put a lot of work into this lanterna magica effect. Back behind us, we had the LED screen with the high-def animation, and in front of us we had spaghetti curtains and through the whole concert these were opening and closing all the time. It’s always this high-def, low-def experience, trying to create this lanterna magica effect, kind of like a hallucination or a 3-D, VR sort of thing.

But when you film something like that, it becomes very 2-D. So we looked at it and I was like, “Fuck, we spent all that time curating every moment in the show, visually and texturally, we can’t give up there.” So I got the original animation that was made for each song and we added it in front of the film. It’s almost like you add the fourth wall. When you’re there in the room, you see the animation very high-def in its entirety, but the problem you have when you edit a film is you see each thing for only a few seconds. You keep jumping between each visual. So I was just like, “Let’s put that layer on top.”

We spent a few weeks layering and adding to it, because for me it’s always the balance between the digital and the analog. I really like when it’s equal, it’s a twist. If it co-exists, it’s a turn-on for me. Putting the fantasy there in high-res, it kept the balance just right.

It also helped because we only filmed one show. Some songs are more abstract and you want more animations, other songs you want more close-ups. So by adding this fourth wall we made the songs a little more different from each other.

A lot of my work on stage can be very introverted, so I tried to capture that. There’s two ways of singing on stage: looking into everybody’s eyes and merging with the crowd; and the opposite, humming to yourself, like Arthur Russell’s music. I wanted to represent both.

Mask: James Merry

How does the Cornucopia show exemplify the environmental justice issues you’re concerned with?

For me, it’s always the whole picture. This idea that seems very sci-fi and far-fetched — oh, let’s all the women and children go to an island and play flutes, with faces that are becoming plant sand flutes that are becoming synthesizers — for me, it is very environmental. It’s a statement. It’s about saying no to all the films being made today that are post-apocalyptic. It’s about all the self-pity of civilization, of the slow-mo Titanic crashing, and the self-destructive element of Western civilization, the narcissism in it. It’s all about watching a slow-mo narrative we’re not a part of. It’s very US, UK, European-centered, white, male — and thankfully, you know, there are so many other narratives.

Like Iceland, we never had an industrial revolution. Or Southeast Asia, Thailand, South America. Women, queer people, all the other races. There’s a lot of other stories. And of course we are facing a very difficult situation. But I think we will overcome it, or for me, it’s more about taking it for what it is. In my opinion, the apocalypse has already happened, so what are we going to do with the remains? Okay, we have lost half our species. We will lose more. There will be mutants of radiation and toxicity. I think the future is somewhere there, and I think biology can handle it.

So it is a statement, in a sense. When the concert opens, it is like a sci-fi fantasy, but then it is a sobering moment when the Manifesto runs by. Where I’m actually like, Snap out of it! and talk about the Paris Climate Accord. It’s like, if we think of whatever climate accord we’re trying to reach as completely unreachable, then we’ll never be able to meet these goals. The only way to do it is to imagine a future and then step into it. We have to write climate accords that we can reach. We have to keep tweaking it until we get it right. And I’m hoping the next generation, when they take over, they’ll think about it in a different way and come up with different solutions, green ways of living.

Photo courtesy of Santiago Felipe

How would you describe the relationship between activism and art?

I used to think of them as very separate, maybe because I was brought up by hippies. I thought putting activism in your lyrics was an ugly and strange place for it. Like Woodstock, with the acoustic guitar, passive and mellow, and then the very aggressive activist lyrics on it. It seemed like a strange music genre. Maybe I just needed time to digest it. By the time I did “Declare Independence,” which was on Volta in 2006, I almost did it as a joke, because for me it was so absurd. I had done a lot of activism in Iceland, but I didn’t feel like you had to sacrifice the music for it. Why all unite in a bad song? Why can’t it be a good song? So “Declare Independence” was written as a sort of rebellion against myself, because I was so against activism in music. I thought it was so pathetic that I actually thought it was hilarious. It was some strange kind of absurd joke.

But at the same time I feel very sincerely. That song came out almost 20 years ago, and colonialism is still vibrant in Europe, which is insane. But when I wrote those lyrics, I also wanted it to be [about] personal politics. If it was both political and personal, it would erase these boundaries, or rise above it.

So I tried it on. But for me, in general, these things are pretty separate. I tried some things in the ‘90s, like being part of celebrity campaigns for children with cancer or something, a cocktail situation, and it just seemed like turning up for a photo moment and going back home — that’s not really how I do things. I like to be part of the whole thing. So I decided instead of being in a little bit of 50 things, to put all that energy into one thing. For example, fighting fish farming in Iceland. To put all the eggs in one basket, and try to pick a course that hopefully, if it works, can make a change. Not too big that it’s impossible to do it, because it’s very important to keep hope alive in environmental things. You are actually walking the walk.

I’m blessed that I come from the biggest untouched area of nature in Europe. We can actually fight fights there. We can actually win them. We can actually protect it. I take it very seriously, this kind of think globally, act locally.

Would you say you’re optimistic about the future?

Yes. I mean, I think so. I’m very excited about 2025. There have always been apocalypses. We had Noah and the flood, we’ve had plagues. There’s always been this narrative, and now I think it’s about being active and being part of the solution. And also to have the courage to imagine a future and be in it, to be it. To inspire your work locally in your community or however you think you can make a difference. It is important. I do find it hard to watch some of these post-apocalyptic shows or films. It’s like you’ve just given up — the nihilism, the self-pity, it’s like it’s cool to give up. [Laughs] I don’t think it’s cool to give up. So it’s about figuring out how we can keep humanity and soul in the future worlds we’re building, where nature and technology can collaborate. But I think it is possible. I think with imagination, biology can take it, biology will be fine. Biology always wins.

In my opinion, the apocalypse has already happened, so what are we going to do with the remains?

Photography: Vidar Logi

Styling: Edda Gudmundsdottir

Makeup: Daniel Sallstrom

Hair: Ali Pirzadeh

Nails: Texto Dallas

Set design: Andrew Lim Clarkson

Masks: James Merry

Editor-in-chief: Justin Moran

Managing editor: Matt Wille

Music editor: Erica Campbell

Publisher: Brian Calle