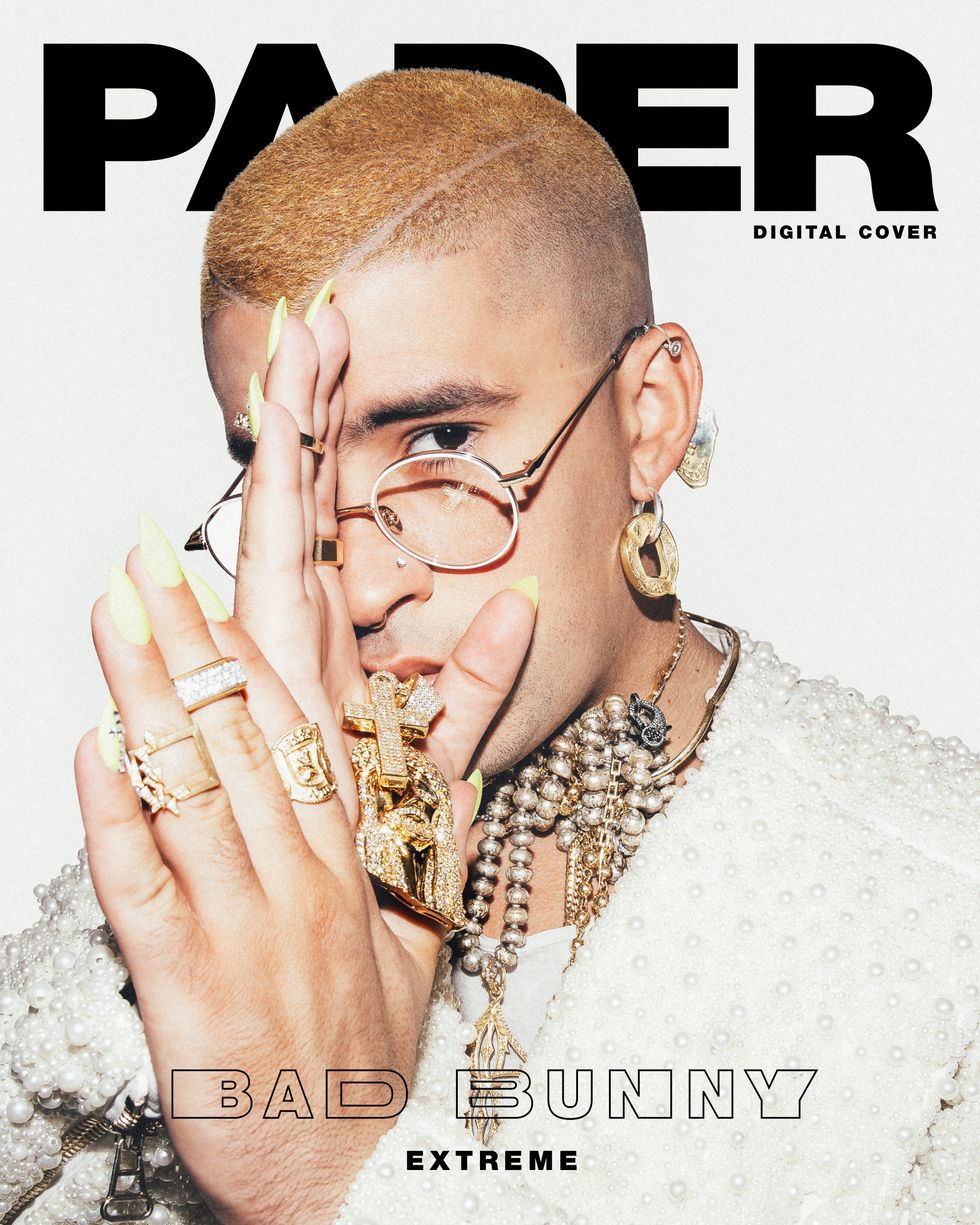

Extreme

Bad Bunny Just Hits Different

Story by Jhoni Jackson / Photography by Robert John Kley / Styling by Star Burleigh

06 June 2019

Bad Bunny sounds tired on first "hello," but his energy soon peps up. When we speak over the phone, he's in the midst of wrapping up a U.S. tour, and a few nights earlier, he'd sold out Madison Square Garden. I ask how he feels about that milestone: "How do you think?" he replies. "Happy. Proud."

The 25-year-old Puerto Rican trapero's celebrity status exploded last year after a series of mega-hits, most notably "Mia" featuring Drake and "I Like It" with Cardi B and Colombian reggaetón star J Balvin, that charted high across multiple categories (the latter, of course, hitting number one on the Hot 100). In November, YouTube announced his placement as the third most played artist globally (just behind J Balvin, with fellow Puerto Rican artist Ozuna, who he also collaborates with, at number one).

Related | Seeing Red: Zendaya to the Extreme

Dropping his debut LP, X 100PRE, last December, Bad Bunny showcased unexpected versatility, blending styles like pop punk and vaporwave into the fold of Latin trap and reggaetón. Its title, pronounced por siempre, means "forever" in Spanish — and the album, which lived up to the hype built off years of Latin chart-topping singles, felt undeniably like a declaration of his staying power.

In Puerto Rico, for a few years now, his music has been ubiquitous: Across the archipelago, any time of day, every day, the thick and booming, subtly garbled baritone of Benito Antonio Martinez Ocasio — el Conejo Malo — can be heard blaring from a passing car, pouring out the doors of a bar, on the radio, floating along the beach or reverberating from a neighbor's apartment. You can even hear it onstage at queer drag shows.

Sunglasses: Christian Roth, Tank Top: Rick Owens, Jacket: Ih Nom Uh Nit, Earrings: Wai Yan Choi, Choker: Hearts on Fire, Pearl Necklace: Loree Rodkin, Cross Necklace: Jason of Beverly Hills, Medusa Necklace: Jason of Beverly Hills, Rings (Left to Right): Loree Rodkin, David Yurman, Swati Dhanak

Part of Bad Bunny's allure for queer fans is undoubtedly his high regard for his own individuality and a respect for everyone else's right to the same. Even more than in his music, that messaging is projected through a distinct style. He's fond of bright clothing with flamboyant patterns, micro sunglasses in angular slivers or sideways ovals, graphic designs carved into his buzz cut and colorfully painted nails. (A nail appointment even had him running late for his PAPER shoot; he arrived with refreshed yellow, almond-shaped claws, like the ones he debuted at the Latin Billboard Awards in April.)

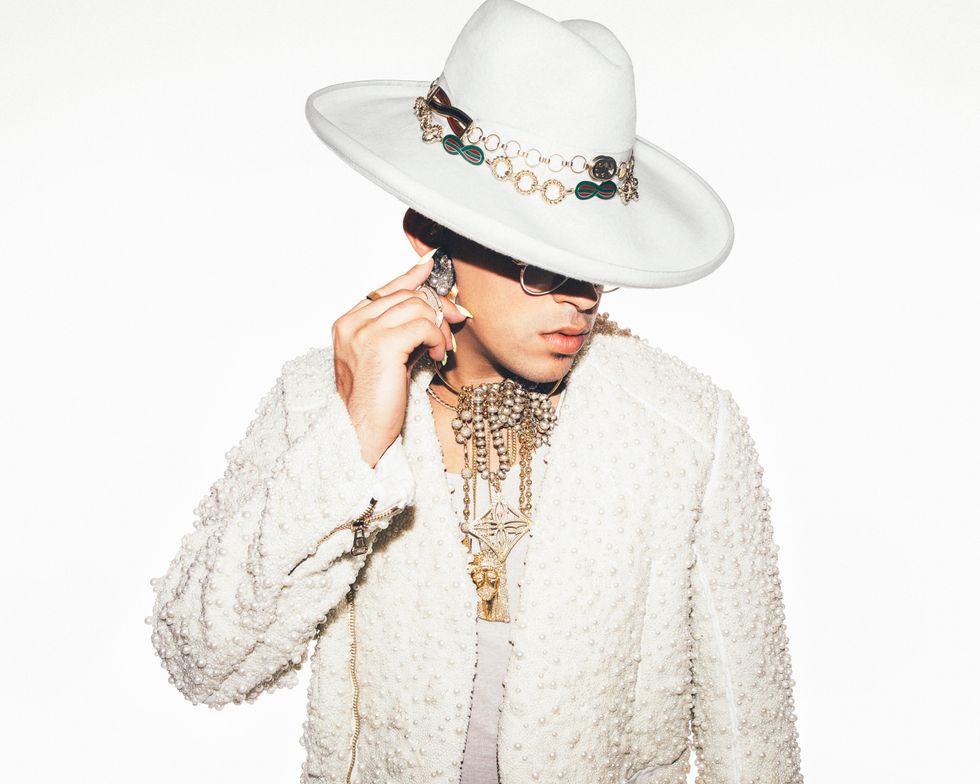

His dress has been described as weird, gender-bending, kooky, flashy, tacky, innovative — and to some extent, all of that is true. Bad Bunny has always championed style, he says, rather than fashion per se. Growing up in Vega Baja, a town of just under 60,000 people 30 minutes from San Juan, he remembers wanting "to look a certain way, or dress a certain way," he says. "So that when I show up someplace, people can identify me — not just now that I'm famous, but always. Like, 'Look, Benito's here.'" (This interview was conducted in Spanish and Bad Bunny's responses have been translated into English.)

Now that millions of people can identify him, his style occasionally becomes fodder for online trolls who question his masculinity or sexuality. (See almost any of his Instagram posts for proof, or recall the time last summer when, after calling out a nail salon in Spain that denied him service because he's a man, his Twitter was flooded with homophobic comments.) But Bad Bunny chooses to ignore the comments and sticks by his signature looks, reinforcing his self-love messaging in the process.

"I'm not telling people, 'Hey, paint your nails or color your hair, do this or do that,'" he notes. "I'm simply saying... do what makes you happy, and to never limit yourself... Just be yourself, and be happy in that. And also not to criticize or judge, because maybe for you something's bad or not bad — if you like or dislike something, that doesn't mean everyone has to share your opinion. It's about that: respect. It's so basic."

In the context of the cishet patriarchy, that's some pretty queer branding — although, to be clear, Bad Bunny has never himself identified as anything but a cishet male. I asked about his familiarity with his queer fanbase which, particularly in Puerto Rico, includes the alternative drag scene of San Juan, where social and political critiques live in the same realm as sex positivity, future-forward fashion and trend-driven camp. He knows performers are incorporating his music onstage: "I've seen videos," he says. "I know about it. It's cool."

Clothing: Versace, Boots: MSGM, Sunglasses: Anna-Karin Karlsson, Necklaces (From Top to Bottom): Adinas, Moschino and Hearts on Fire, Earrings: Hearts on Fire, Bracelets: Miansai, Rings (From Left to Right) Swati Dhanak, David Yurman, Jason of Beverly Hills, Jason of Beverly Hills and David Yurman, Bracelet H. Stern

Hearing reggaeton and trap at queer events in San Juan isn't uncommon and there are some urbano artists who've aligned themselves with drag performers or who, like the late Kevin Fret, were queer themselves. Still, there's something about the ease with which Bad Bunny branches out beyond masculine norms, shaking off contrarians with lyrics like, "How I am, what I say, what I do, what the fuck does it matter to you?" It's a line from "Caro," a self-love anthem that's perhaps one of Bad Bunny's most popular tracks for local drag performers. Released a month after X 100PRE in January, its video starred model Jazmyne Joy as his female proxy and included a scene featuring an inclusive fashion show runway of models of varying ages, abilities, races, sizes and genders. Another scene shows Bad Bunny standing on a hill as naked people run by, only their sunset-lit silhouettes visible; one male-presenting person stops to plant a kiss on Bad Bunny's cheek. It happens during a slowed point in the track where Bad Bunny contemplates, "Why can't I just be? What harm is it to you? I'm just happy." Later, he and Jazzy-as-Benito kiss, the ultimate symbol of self-love.

When I ask why he thinks his work resonates so strongly with young queer people, he says, "It's a message of respect, of freedom. I think they feel comfortable, and they feel, I don't know, like part of what I'm doing. They don't feel excluded from the group, but instead, like, 'We're wanted here; we can be ourselves here.'"

Self-love, inclusivity and LGBTQ acceptance aren't the only progressive ideas reflected in his music. On "Solo de Mi," he sings about autonomy after terminating a romantic partnership: "Don't call me baby, I'm not yours or anyone else's, I belong only to myself." In the video, the theme was translated as a statement against gender-based violence. It's a topic that's particularly salient in Puerto Rico right now; late last November, only weeks before the video debuted, protestors had camped outside La Fortaleza (the governor's mansion) in Old San Juan for a full weekend, asking that the Governor, Ricardo Rosselló, declare a state of emergency after the year's femicide toll in Puerto Rico reached 41 women, with at least 23 of them murdered by intimate partners.

Posting a clip of the "Solo de Mi" video on Instagram, Bad Bunny emphasized his point, condemning Puerto Rico's high rates of violence against women and saying, "The time to take action is now." He called for respect for women, men and all life: "Less violence, more perreo," he wrote.

A few weeks later, he and long-established Puerto Rican rapper Residente, met with Governor Rosselló in person. The meeting was unscheduled, the result of several late-night attempts to gain entry into La Fortaleza before they were finally welcomed in around 2:30 a.m. According to Residente, they discussed the island's issues with crime, education and debt, as well as the Financial Oversight and Management Board installed by the U.S. as a result of the latter.

But as progressive as Bad Bunny is, he's still an artist whose primary lane remains urbano music, a genre, like so many others, where misogyny and machismo culture run rampant. And even if he himself mostly eschews those tropes, he still shows off the same swagger as his musical peers on songs like "Mia," with possessive lyrics like, "Dile que tú eres mía, mía/Tú sabe' que eres mía, mía" ("Tell them that you're mine, mine / You know that you're mine, mine"), that stand in stark contrast to the message of independence in "Solo de Mi."

But ultimately, he's offering up proof that artists like him, people who are trying to do something different, can not only exist in the industry but also find success within it. The foundation on which Bad Bunny stands is a positive one — and could be impactful for urbano music, as well as other popular genres. The ripple effect of his continued celebrity could be far-reaching.

"It's not so much about changing the genre, but instead the way of thinking, not only in the fans but in the artists," he says. "I'm letting people know there's another way that maybe didn't exist, or it wasn't developed. It's not about changing what's already established, either, but instead about opening doors for other messages — another wave, you know?"

Photography: Robert John Kley

Groomer/Nails: Briseida Rubio

Stylist: Star Burleigh

Stylist Assistant: Devin Wright & Deidric Harris

Location: SON Studios