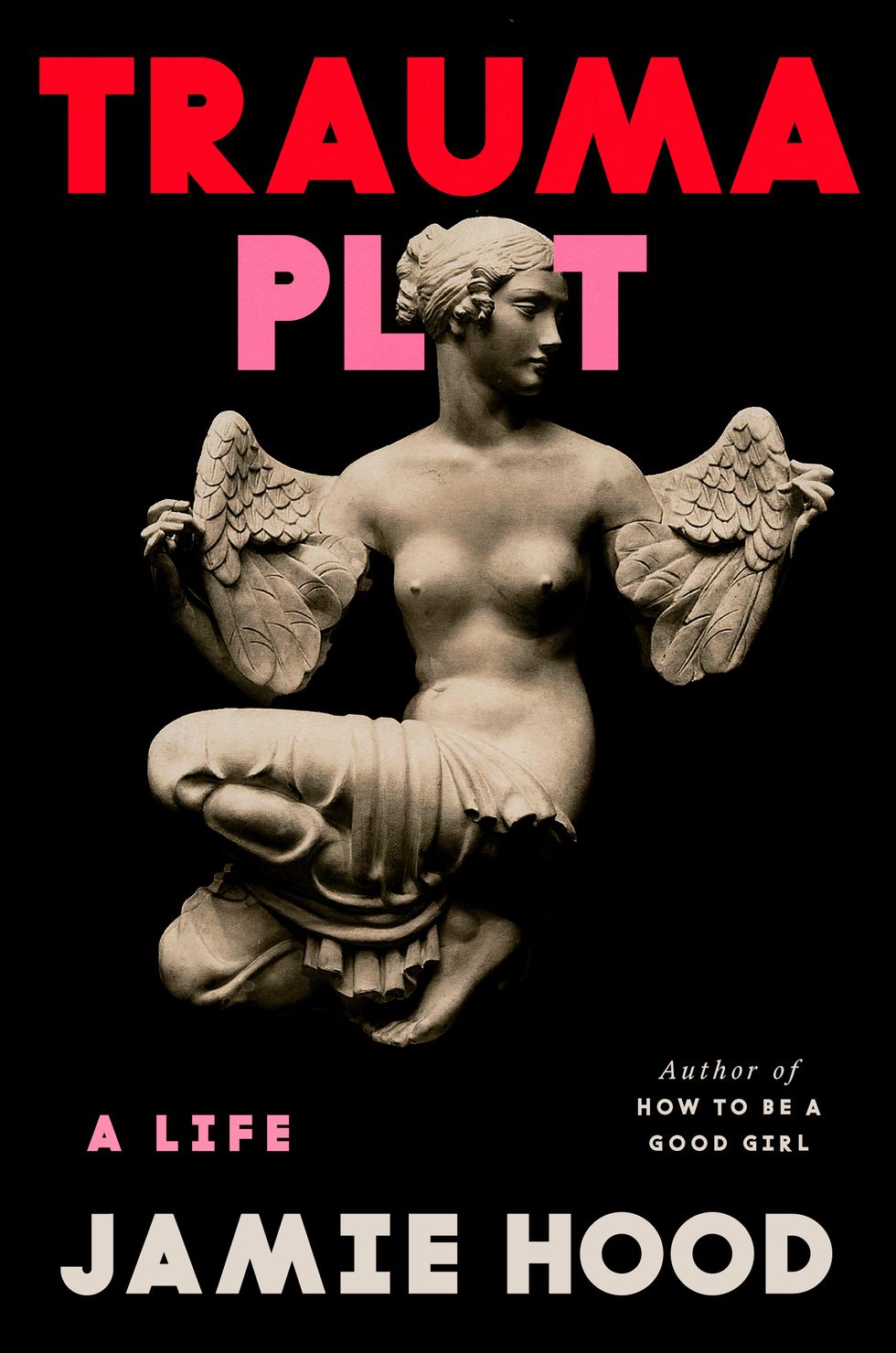

Jamie Hood's 'Trauma Plot' Refuses Definition

Apr 09, 2025

Jamie Hood’s new book, Trauma Plot, is not a memoir — it’s “A Life,” as its subtitle heralds. “There would have been this imperative to stick to some historical factuality,” Hood says of her decision to stray away from calling the book a memoir. “I wouldn’t have been able to be as experimental with it, either.”

Trauma Plot, out now via Penguin Random House, takes its title from one of the more prominent literary criticism discourse threads of the last five years — the idea of the “trauma plot” raised by critic Parul Seghal in the New Yorker. The essay, which made significant waves in the online literary community, posits that the trauma plot “flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom, and, in turn, instructs and insists upon its moral authority;” Hood’s book pushes directly against this idea by illustrating healing through its own medium.

The book is split into four sections: an introduction that sets the stakes against the idea of the trauma plot, followed by four chapters — each in a different narrative style and/or point of view — detailing a series of traumatic events in Hood’s life (rapes, specifically) and the way “these kinds of violence can contaminate decades.” The chapters range from a third-person narrative wherein Hood becomes a character of her own making to a series of journal entries written after therapy sessions. Together, they form a trauma plot that Hood has admittedly found quite healing.

“I went into the process very resistant to that idea,” Hood says of the book’s personal capacity for catharsis. “And then I wrote it, and it did help.”

Below, PAPER caught up with Hood ahead of Trauma Plot’s release to discuss creating friction, shaping the book’s unconventional narrative and the place of the trauma plot post-#MeToo.

How are you feeling with the release looming?

I am feeling stretched thin, very stressed. I mean it’s good, it’s exciting, it’s like getting to the end of the marathon. I have all these things — like, I’m going to a lingerie fitting for Dirt tomorrow.

[Laughs] I think I’m answering in a very logistical way because it’s hard to imagine the way it’s going to be assimilated in a cultural or aesthetic sense. The publishing apparatus takes over in a way… the manuscript itself I finished last April. In that regard, some of the work feels far at that point. I’m also nervous. All the reception has been very good, but it’s also a book about rape. We’re not in a great moment for survivors or, like, trans people, queer people. I didn’t expect the book to be coming out at the dawn of the second Trump administration.

Yeah, how do you feel about releasing it in this moment?

Unsettled. I mean, I wasn’t like, “I really hope Kamala Harris is president when my book comes out.” But there was not a world where I imagined Trump getting back into office. It’s my stubborn optimism.

I talk in the introduction of the book about these death knells of #MeToo that never really got off the ground. I was just reading a great essay by Rayne Fisher-Quann about the Amber Heard trial — she talks about how calling it backlash against a movement feels almost disingenuous, because the movement hasn’t even graduated above a purely superficial level before the supposed backlash began. Which feels incredibly demoralizing.

I do think, in another sense, it creates friction. Maybe my book will have a more intense impact because it’s coming out against the grain.

The book is split into a few sections that are each written very differently. What was the writing process like?

Very complex, very protracted. I started working on this 10 years ago. There have been many different drafts. I originally imagined it as a book of poetry. And then I tried writing it as a straighter memoir, and that also felt very insufficient. I didn’t feel like I was being honest, in some way. I tend to get formally restless as a writer and a reader, I read across all sorts of genres, five or six books at a time. My mind requires a lot of stimuli.

The book’s current form came about when my agent forced me to sell it [laughs]. It was originally going to be nine sections — poetry, memoir, and then lit crit about rape narratives. When I started writing, I began to feel like I was running away from the actual story I was trying to tell. I was imposing a strict formal machine to keep myself from looking at the things that had happened to me. So I condensed what I’d imagined to be 150 pages to three paragraphs on A Little Life in the introduction.

The first chapter was the hardest, the autofictional one that’s an homage to Mrs Dalloway. At first I wrote it in the first person, and it came off as so cheesy and dishonest. So I tried it in the third person. I was like, What if I imagined myself as a character in my own life? I was thinking about Woolf, I was thinking about Clarice Lispector. I kept reading The Hour of the Star. As soon as I switched to third person, I felt free to be a little looser with it. I was like, what if I play around a little and imagine these are not events that happened to me — maybe the facts can be a little subsidiary to imagining a narrative and telling a true story. Once that chapter clicked into place, the rest of the book just sort of came with it.

These kinds of violence can contaminate decades.

Were those cut sections just left on the cutting room floor?

The poetry I didn’t even really touch — it was a book-length poem I wrote a decade ago. I tried to rework them, and they just didn’t feel right. And the lit crit stuff, I didn’t really touch it — I didn’t feel like I actually needed a 40-page chapter on Hanya Yanagihara to tell the story of my rape.

The trauma plot of it all, which you address in the introduction — was that always a framework for the book or something you stumbled into later?

The last time I picked up the book and said, “Actually, I do want to write this” — because there were many times I questioned whether or not it was worth it on a personal level, or even on a political or analytical level — the idea of the “trauma plot” is what made me feel like I had something to say. Especially after reading the Parul Seghal essay in the New Yorker, which I talk about in the introduction. What felt strange to me was the way her taxonomy of the trauma plot became a way for anyone involved in art or literature to form their own backlash against these narratives of trauma and #MeToo. It was seeing the way that article bled into the rest of culture, by weaponizing the language of the article — that’s where I was like, Oh, I know what I want to do differently. I know what I want to say.

Thinking about it as a critical framework to work against helped me think about what the intellectual stakes of the project were. I’m very resistant to imagining the things that happened to me as having any consequence. So talking about the trauma plot and situating my own narrative within a critical framework allowed me to say, Oh, there are political stakes. I didn’t feel like I had to dismiss myself.

Tell me a bit about the subtitle. Why did you choose to call it “a life” instead of “a memoir”?

Some of these decisions happen behind the scenes — I felt compelled to have a subtitle. I forget the original one I suggested, it wasn’t great. My team suggested some others, but nothing seemed to work. I felt very resistant to calling it a memoir, because it’s not a conventional memoir. I was concerned also about what kind of readers it would reach if it was called a memoir — what the stakes would be. I wouldn’t have been able to be as experimental with it, either. Like, are people gonna come at me and be like, Well, you definitely didn’t see a ghost, so you must be lying about having gotten raped. There would have been an imperative to stick to this sort of historical factuality. Not that memoirs, in my opinion, should be beholden in that way. And I was thinking about how these kinds of violence can contaminate decades, which they did for me.

The shifts between the sections of the book are pretty drastic. When in the process did you decide the chapters would be from different POVs, with different forms?

They are sort of drastically opposed, that’s true. There was a point where I wondered if it would be accessible to readers — like, do I need to have recentering meditations between chapters or something like that? But I didn’t want to do that, it felt corny to me. One of the things that felt important to me was to not coddle the reader. It wasn’t pretty to live through this, why do I need to stand on the edges of this idea?

I knew I wanted to do a first-person and a third-person chapter. Once I had those two going in tandem, I knew I didn’t want to jump between them — I wanted to do something with my diaries. The third chapter organically formed from there, where I decided to be even more distant, to act as a kind of biographer. One of the things I was interested in during this process was, especially formally: What does it mean to have an unstable relationship to the way you understand your life? I think we all do.

The book, on a formal level, feels like an exercise in constantly navigating questions of distance and proximity to the subject. And on top of that, it did feel fun to think of myself as a character. It was like, What if I had had control over my life and had been able to stop this? It allowed me to play with that idea a little.

And then I wrote it, and it did help.

I saw you’ve been recording the audiobook, too. What’s that been like for you?

It’s been really tough. Honestly, I think it was tougher than the writing. I write aloud — I have to say the things as they’re coming. But writing imposes distance, because it requires an analytical part of you, right? So even when writing about my rape, I’m still the architect of the narrative. When I went in to record the audiobook — well, for one thing, I’m not an actress, it felt very unfamiliar to me. I was recording for eight hours a day in a weird little cocoon.

There’s something about reading it straight through. You’re suddenly just performing, there isn’t distance. You’re a conduit for something. That enabled me to re-experience some of the awful things I had written. I did the last 15 or 20 pages in a single, uninterrupted take. It was almost like casting a spell. I felt possessed, at the end of it I just took a break and started sobbing. I couldn’t stop sobbing for like 20 minutes. I didn’t even cry when I finished the book. I just kept waiting for it to happen. It turns out I just needed to say it out loud.

This is a big question, of course, but do you feel like the process has been cathartic?

I went into the process very resistant to that idea. I talked to my therapist quite a bit about it — I was like, I know this isn’t gonna heal me. I don’t want to say writing my book cured me or something, but I did come out of the process feeling much more at peace, in a way that was very unanticipated to me. I’m fundamentally an optimist, but I try to temper expectations about my own life. I told myself, This isn’t gonna help. And then I wrote it, and it did help.

Photography: Matt Wille

MORE ON PAPER

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October

Entertainment

Matthew McConaughey Found His Rhythm

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

30 September