It all started with Chet Hanks.

Or, technically, it all started when Chet's parents, Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson, announced they had tested positive for COVID-19 in March 2020 — the first big celebrity case of the virus that for many, and for reasons that say more about who we are as a people than could fill a shelf of sociological texts, cemented the gravity of the pandemic. For artist Isaac Peifer, it was an early inspiration for his pandemic-era celebrity portraiture, a practice he would keep up for over a year, culminating in a new gallery show, titled Cringe: Portraits From the Pandemic, on view July 16 through 18 at THNK1994 in Manhattan.

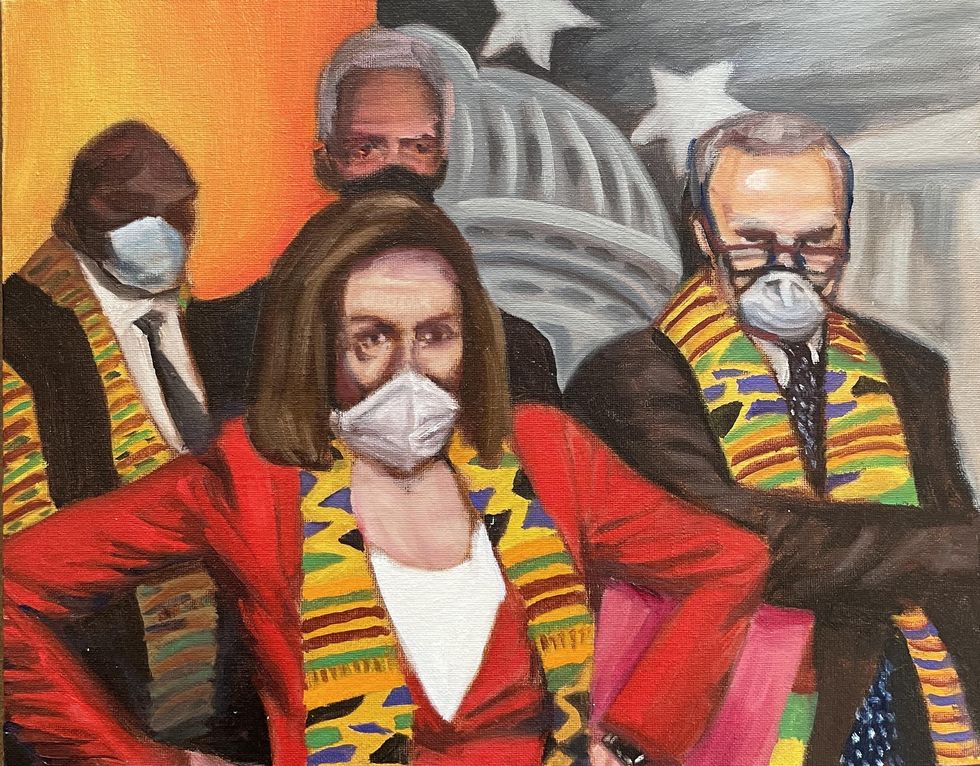

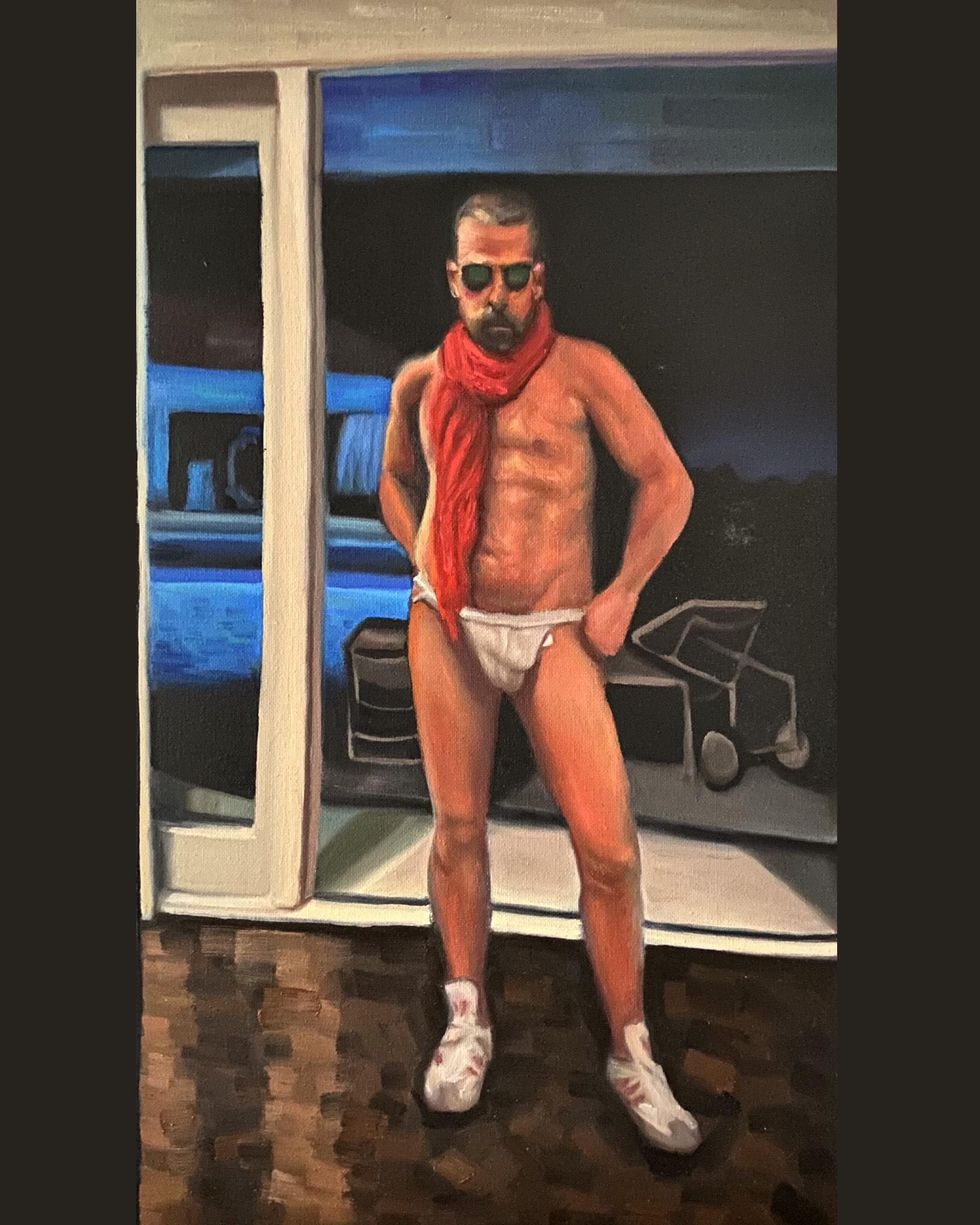

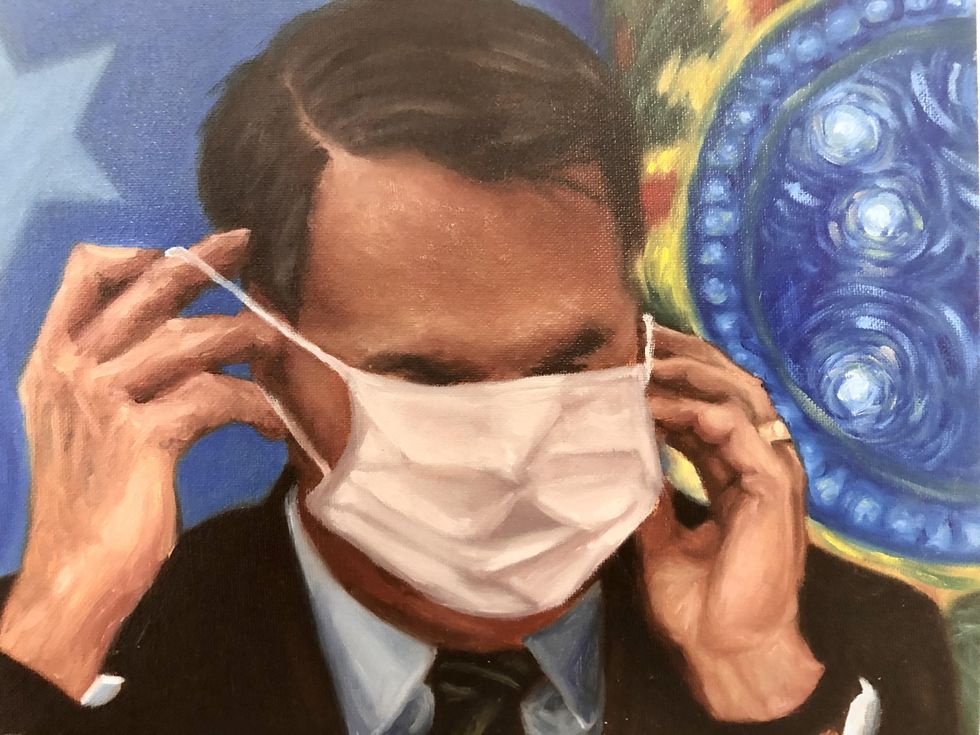

Throughout quarantine, Peifer painted portraits of public figures who captured our fleeting, flattened attention during the last year and a half: celebrities, politicians and otherwise everyday people who'd achieved virality — a term that takes on new meaning in the wake of a global pandemic — at one point or another. (Remember that giant baby?) Cringe is a diary entry of those moments: Gal Gadot, blithely leading an unwanted digital lullaby, hangs alongside Emily Ratakowski as a modern-day Instagram-hot Madonna and child and President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, absurdly half-masked in a portrait titled "Todos Nós Vamos Morrer um Dia." Recreating these contemporary figures in the historically stoic medium of oil on canvas, Peifer in turn bestows his subjects with a sort of goofy gravitas. Through quick brushstrokes, they all appear cartoonish and exaggerated, almost grotesque. As Peifer says, "I don't think I was documenting the celebrities themselves. I was documenting this shift in how other people saw them."

The artist speaks with PAPER about his process, the seedy side of the elite and what the pandemic taught us about interconnectedness.

As you were painting during quarantine, when did you realize that you were creating a series of works, as opposed to this one-off thing?

At the very beginning, when Tom Hanks tested positive for coronavirus and then his son Chet — who would then later reappear miraculously during all this — made a video where he was talking about how his parents have coronavirus but that they're OK and everything is fine. He was very calm about it. I found it to be a very calming video. It helped me sleep at night because at that point everybody thought, "Everybody's going to get coronavirus and everybody's going to die." And here was [Chet,] this very strange character that nobody had ever heard of talking about his famous father and how everything was fine. And so the next day I was like, "I need something to paint because I'm going crazy because we're in lockdown." So I decided to paint him, almost as a gesture of appreciation because I found him to be such an interesting person.

I posted it on Twitter and people liked it. After that, I sort of got into the habit. It was my way of processing everything that was happening: this revolving door of celebrities making some statement about what was going on and most of the time humiliating themselves in the process, becoming [the internet's] "clown of the day."

"Clown" because they're demonstrating how out of touch they are?

They were kind of clowns because — in the same way that normal, average, everyday people were looking for whatever lightning rod there was to attract their free floating frustration and ire and anxiety and fear — celebrities also had this impulse to try to humble themselves. In doing so, it often just came off as insincere, or it backfired because it came off as un-self-aware. It was this moment where celebrities really couldn't win; they were probably afraid of being seen or seeing themselves as the bad kind of rich people. So they have to take a stand against everything that was happening, but in doing so they just revealed themselves to be, at the end of the day, no different than the quote-unquote bad rich and powerful people. They still got to bunker away in their little hamlets.

What was your painting process like?

Whoever was getting attention, I would sit down [and] paint that image. I was looking at my phone in my left hand and painting in my right hand, just painting as fast as I could because I knew that these moments were passing so fast but I wanted to be able to share them while the moment was still relevant.

I found that that fast painting naturally made these sort of cartoony portraits that were sort of funny but the effort, I feel, was earnest. It was this mixture, to me, of irony and sincerity; it wasn't purely cynical that I was painting celebrities because they were having a moment of vitality. It was partly that, and it was partly me earnestly trying to document everything that was going on in the world through a lens of social media and celebrity. I was treating it like a chronology of everything that was happening, because the moments themselves were so brief and forgotten about.

I'm curious about your notion of "cringe" for this show. What does cringe mean to you?

Cringe, to me, is when earnesty backfires. We've been in this period of irony for so long, and there are these periodic calls to return to some sort of sincerity that never really seem to take hold. I wonder if there is something about the digital age that sort of naturally leads to a dominance of irony? There were some moments during the pandemic where these moments of [earnestness] that went viral because it made people feel good — I'm thinking about that guy who drank cranberry juice on a skateboard listening to Fleetwood Mac.

If it feels like it takes some sort of effort, it's just cringe. It's such a nebulous concept. In the age of irony, cringe is what happens when earnesty can't quite break over the barricade of irony. The more you're seen to be a person of status, the harder it is for your [intent] to be understood as earnestness and not as cynicism.

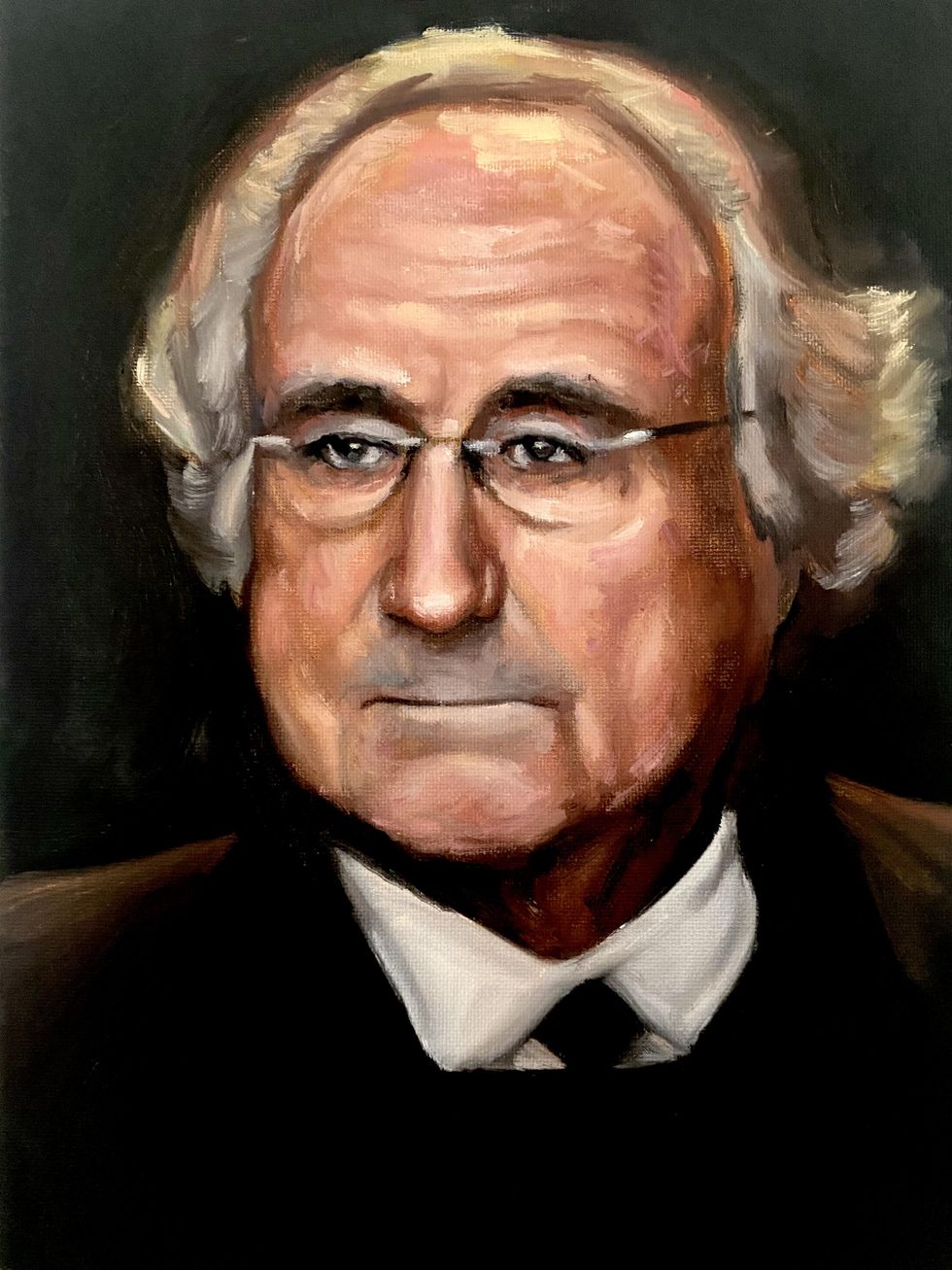

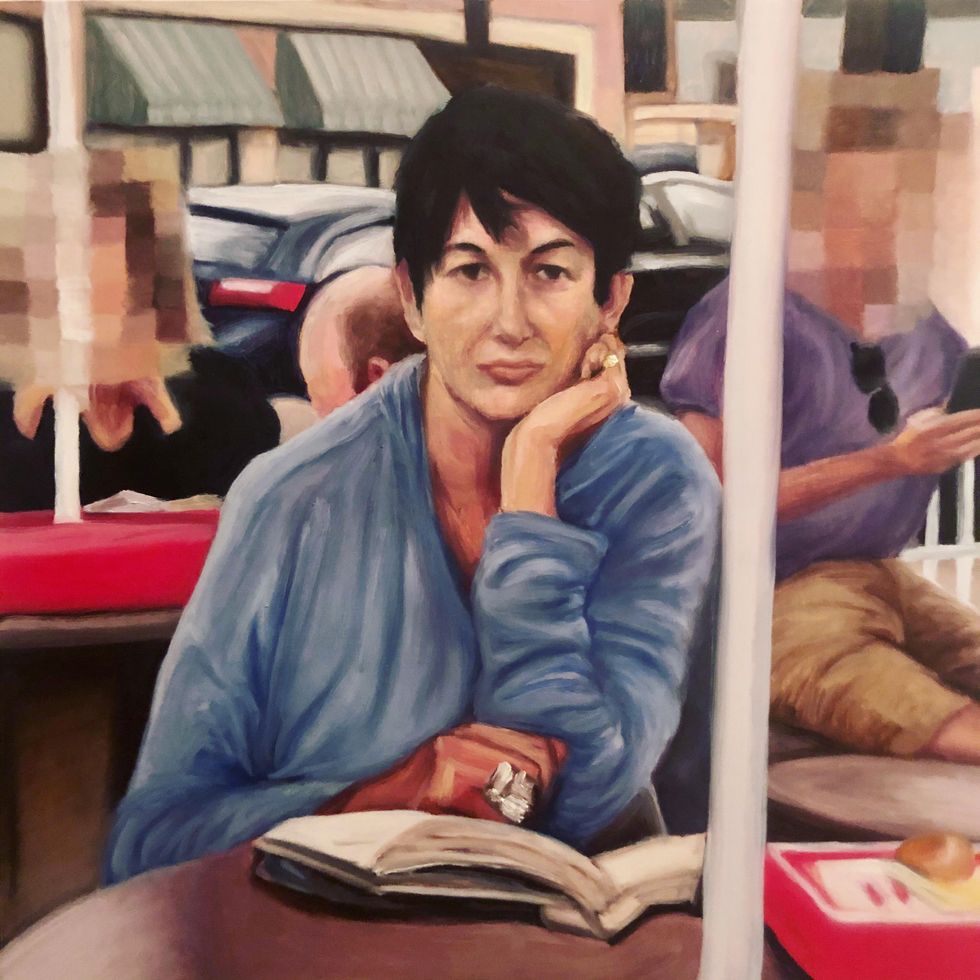

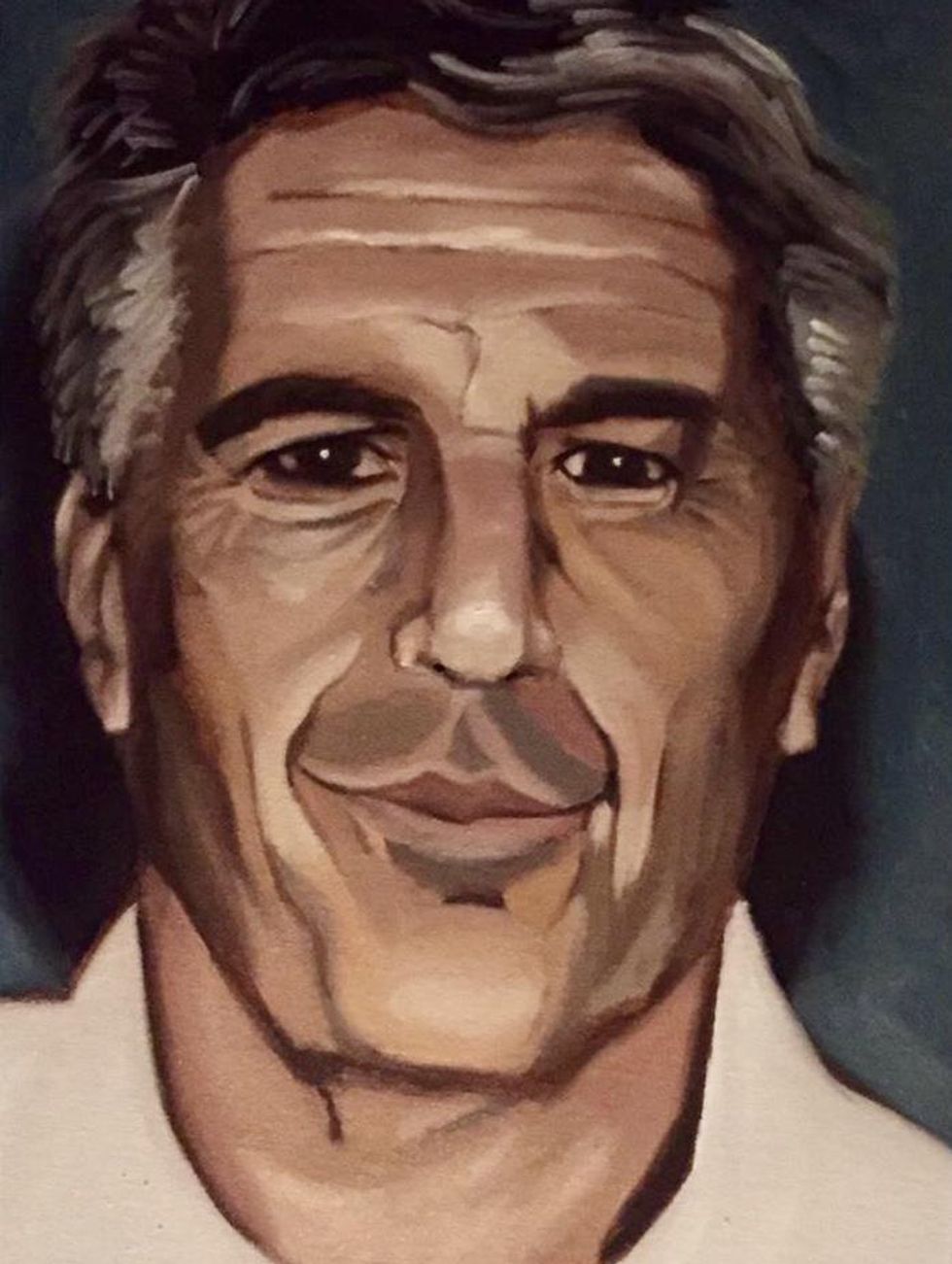

I feel like people might be confused as to why somebody like Adele would be included in a show with portraits of Ghislaine Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein — I don't think I'm creating a moral equivalent between them. To me, the Epstein saga is the zeitgeist that we live in. It's the maximum realization of the logic of wealth and power. All of these moments that we process [are] under the shadow of what Jeffrey Epstein represents, which is sort of the machinations of money and power and corruption. It removed a certain veneer of legitimacy over the elite, in the same way that watching celebrities bunker down in their mansions during coronavirus tarnished their image as benevolent rich people. There's a lot of understanding that, materially speaking, we are not all in the same boat. We are not all in this together. That was the message that a lot of famous, rich, normally ostensibly well-liked people kept trying to say at the beginning of this pandemic — and that message of unity fell flat.

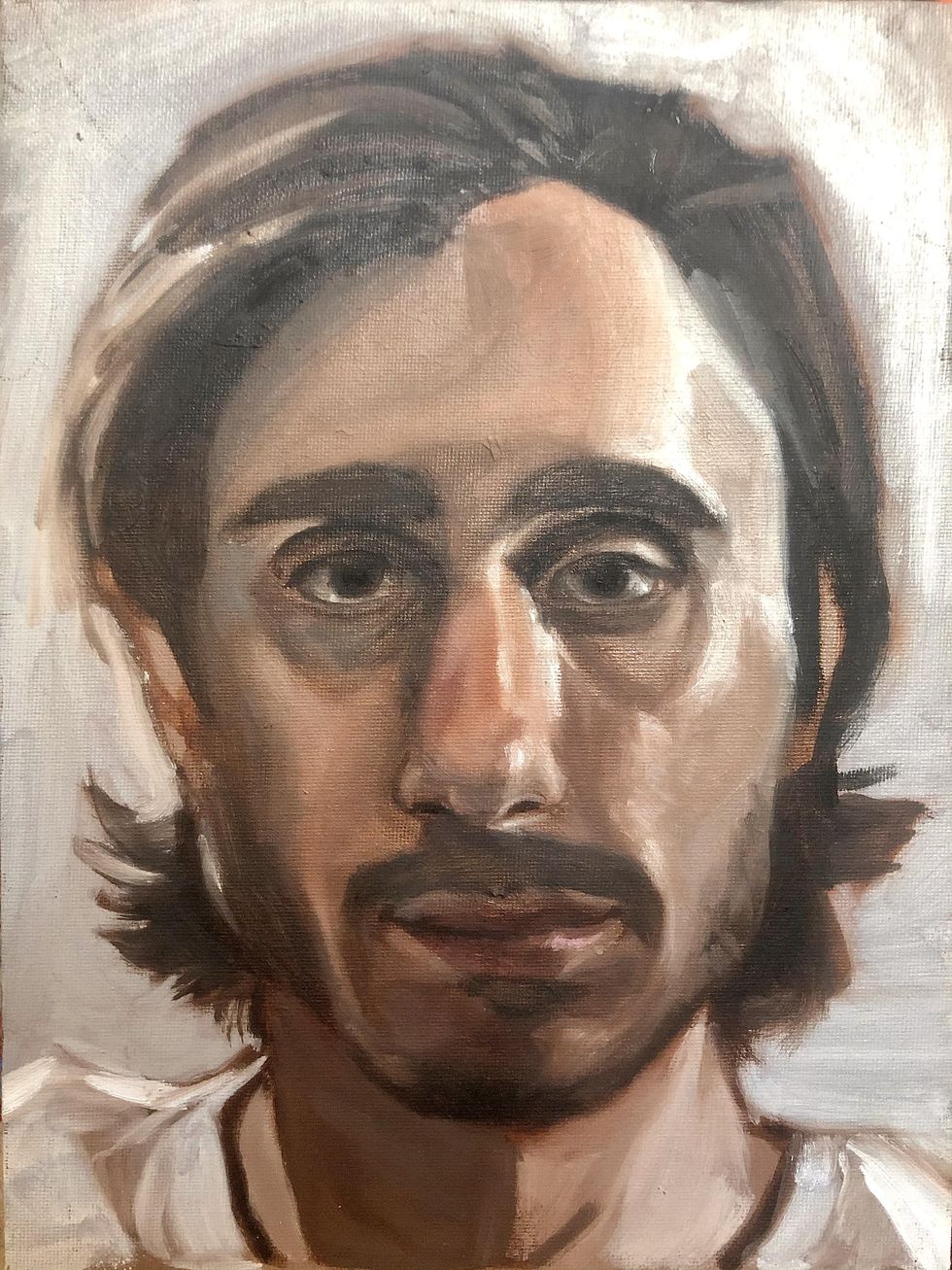

"Quarantine Fatigue (Self Portrait)"

Do you have a favorite portrait in the show, or maybe one that you keep thinking back on?

I have a special place in my heart for the Jeffrey Epstein painting, because that was my first painting where I found painting had a power to it beyond fulfilling my need to take up a hobby. It can engage people. As I would paint all of these things, I would hang them up in the living room salon-style, paintings all over the place. The Jeffrey Epstein one was hanging right above my television, and it was always one the people were interested in. The subject matter is so jarring, so people usually have strong reactions to that one.

I think of it as sort of a pre-haunted portrait. [Historically,] so many subjects of portraiture are painted because they're being honored for greatness [but then] they end up being somehow exposed as villainous in some way. Villainy and power are so intricately entwined, where I think that all portraits have the potential to become haunted by this sort of darkness that's inherent in the subject. With painting Jeffrey Epstein, [I'm] basically pre-haunting my portrait by saying, "This is the type of person who has power in our society. This is the type of person who would get a portrait. How does that make you feel?"

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Photos courtesy of Isaac Peifer