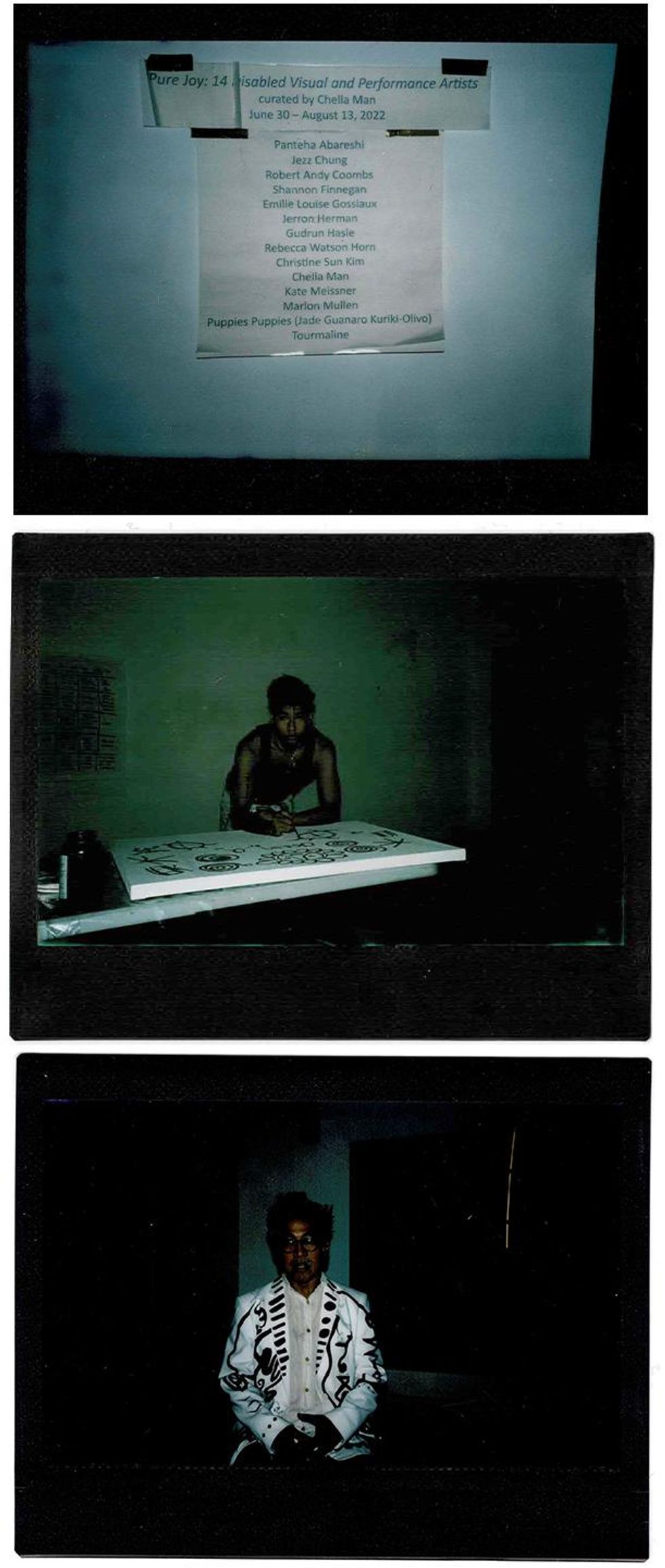

Chella Man is spreading joy with a show featuring all disabled artists, sharing their interpretation of the word. Curating for the first time, the artist, director, producer and author exhibits the work of 14 artists in PURE JOY: 14 Disabled Visual and Performance Artists.

Held at the 1969 Gallery in Tribeca, the show, which opened on June 30 and runs through August 13, matches the diversity of the artists themselves. Their art takes many forms, including live performances, sculptures, paintings, drawings and textiles.

As a whole, the exhibition pushes back against struggle as the focus of disabled artist’s lives, serving as a "reclamation and celebration of humanity." By requiring that artists explore how they experience joy, the show "acknowledges the persistent tokenization of disabled creators, contradicting this cycle by centering ideologies of pleasure rather than pain."

"I hope that it shocks people with how vast and multifaceted we are," Man says of the exhibition. "There's so many different interpretations of the way we approach joy. There's so many ways we are alive, and I think, overall, I just want people to understand how capable disabled people are of living out beautiful, fulfilling, joyful lives."

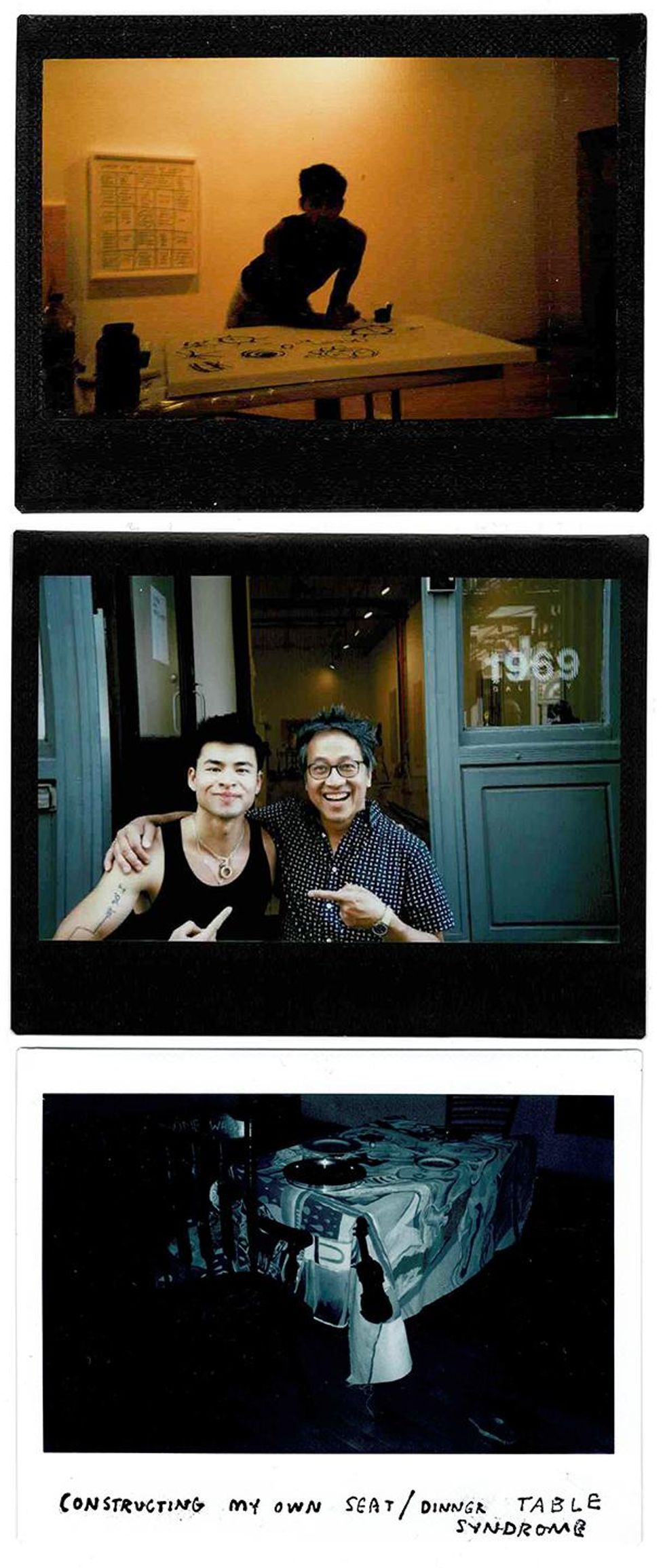

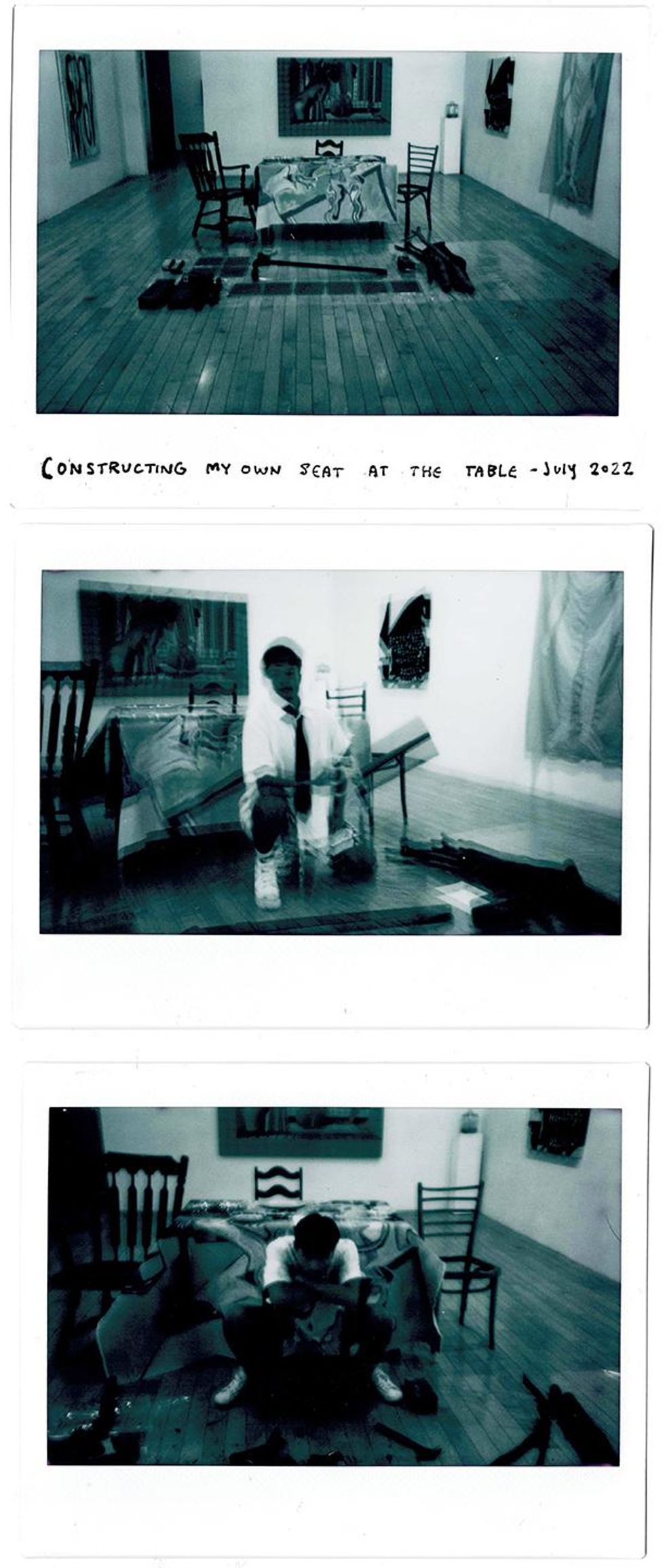

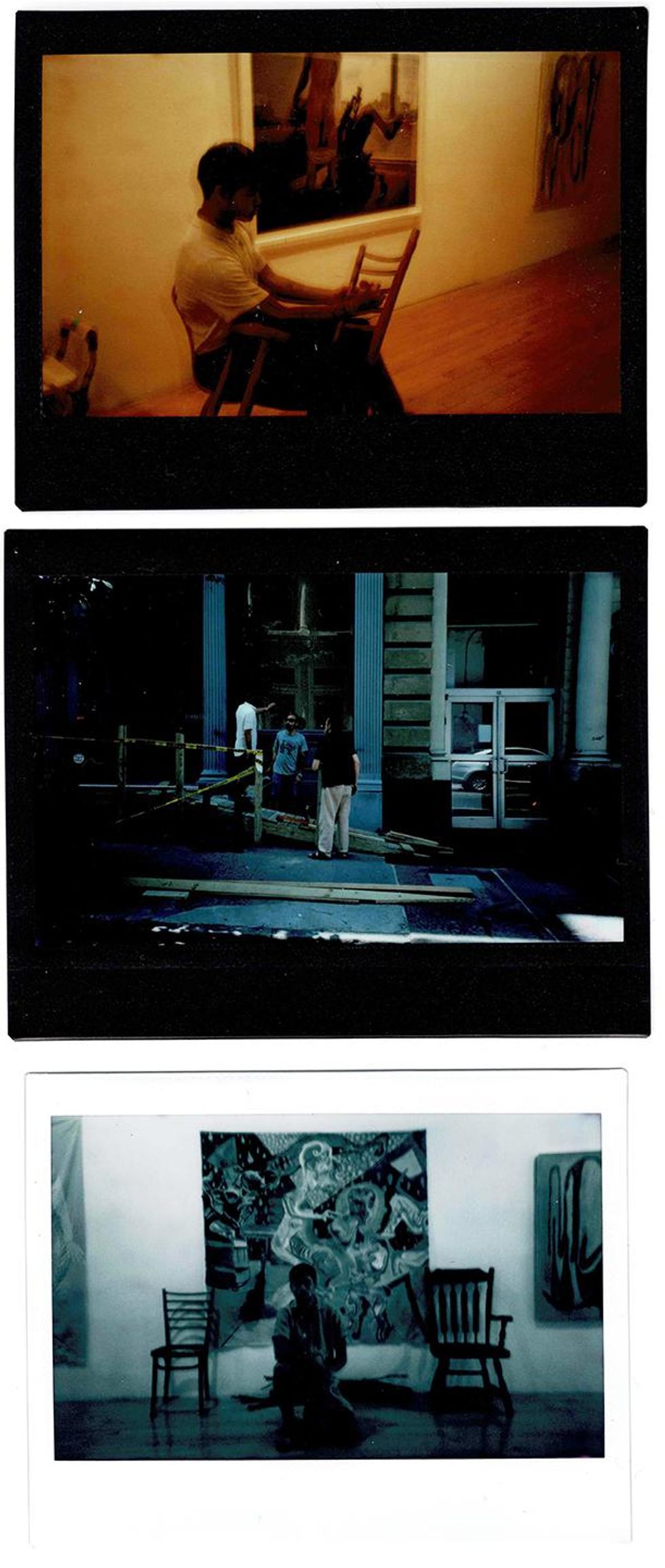

Man also showcases his own work, attempting to navigate taking up space as a disabled, queer, Chinese and Jewish person in “Constructing My Own Seat at the Table.” Accompanying his piece “Dinner Table Syndrome,” the live performance is decidedly uncertain, as his ability to build the chair itself, absent of any formal training, determines the work’s meaning.

Exuberating the theme, Man happily offered us insights into the exhibit, as well as reflections on joy in the disabled community.

What compelled you to center joy in this exhibition?

As a disabled artist, we are often asked to make work about our trauma and our struggles, and this is a way we are tokenized. The word "disability" rarely is paired with the word "joy." For that exact reason, I wanted to expand the stereotypes connected to the word disability and also just the connotations. I would love for that to become more expansive overall, and, unfortunately, there's a lot of people in my community who don’t often think about what their work would look like if it were to just center joy. A lot of the discrimination that we face forces us to feel very heavy emotions centered around the systemic obstacles in our pathways and I don’t want us to feel limited to that. I don’t want disability to only be seen as our struggles.

For you and other artists, what came from the personal exploration of joy, and how did the interpretations differ?

It was really stunning to see the way all the different artists approached translating joy because it was so diverse, just like the people themselves. It mirrored our individuality. Some people chose to approach the word "joy" and the theme directly, focusing on the literary tone of the word. For example, Tourmaline’s image in the show is a portrait of her cat and it's so simple that way because that's what brings her joy.

But, other artists center work directly around their struggle in facing discrimination with disability and, for these, the joy was found in the process of creation. So, for example, on August 13 at Pure Joy Exhibition in 1969, Panteha Abareshi will be performing a live performance, titled Care Transactions. This is all about how painful it is that the medical industrial complex has implemented pain to be such a financial, transactional act, rather than care being something born of love, something led by compassion and empathy. There's a lot of pain in this performance and in a lot of Abareshi’s work. So those are two examples of how artists approached the prompt differently.

What was it like to curate a show for the first time?

It was a dream come true. I felt like I used to make mood boards and collages growing up. It was one of my favorite things, just manifesting all the possibilities in the world. So curating this show was almost like a physical manifestation of one of my mood boards or dream boards, and I could welcome other people into it. And it just existed as a reality. So instead of it being a dream board, it was a dream come true that people could walk into.

What was the inspiration for your piece, "Dinner Table Syndrome," and what does it represent?

Dinner table syndrome is something that happens to deaf and hard of hearing people at the dinner table, especially those who are born into a hearing family or families that don't know how to sign. The dinner table is often known to be a place of connection, but for a lot of us in the deaf community, there is this huge communication barrier and isolation. So I use this performance to alchemize the frustration and stress that I often feel sitting at that dinner table with people that I love, yet [there are] so many invisible barriers. I wanted to alchemize all of that into joy, so I created this painting about how dinner table syndrome feels.

It's a part of a larger installation, which also has three carved chairs that read different phrases. One of them says, "For the one who deserves more space than they have been offered," and this chair is basically a framework of the chair and it's not functional at all. You can't even sit in it because the bottom is broken and this corresponds with a plate that is transparent. The other chair says, "For the one who takes up too much space," and that's a huge wooden chair that corresponds with a dinner plate that is ginormous and looks like this black hole. And the third is, "For the one who has no idea what to say," and that's just a plain-looking average chair, corresponding with a plain average-looking plate.

There is a fourth empty spot at the table and this is where I used the wood from my childhood home’s backyard to literally build my own seat at the table. And I'm no carpenter. I didn't know whether it would sit, remain functional or fall apart when I tried to sit in it. I think that was exactly the point because I had no framework growing up in central Pennsylvania, very conservative, small town. So whether it was functional or not was a statement of its own and I consider the performance to be a huge success.

For "Constructing My Own Seat at the Table," in exploring taking up space as a disabled, queer, Chinese and Jewish person, what have you come to understand about the available resources and framework, as well as the resulting space?

In that performance, I have a lot of reflections again in the diary pieces I wrote, but it came back to community for me. I realized I want to do a second performance in the future and this time I want to still build my own seat at the table, but I want help from my community. And in my diary, I explain maybe that's my dad, but maybe that's also just me reaching out to people who are deaf people who are queer or BIPOC. I'm sure there's a lot of people that I know in my personal circles who have more experience with construction in general. So opening up to others and asking for help when you need it, and also seeking different perspectives that may hold a new approach to the framework that can potentially make the process easier. You can lean on each other. You can move and bond with love, and perhaps build a seat at the table that is just as big, just as sturdy and just as beautiful as the other ones around it.

For Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo’s live performance, "Puppies Puppies," can you talk about the conversations you two had about tattoos and disabilities that gave some inspiration to the art?

For Jade's performance, unfortunately, she wasn't able to perform that night, but I would happily talk about the brain that she included in the gallery show. A little over 10 years ago now, I believe Jade had a brain tumor that she got removed and it's affected her brain ever since: the way that she processes things, the way that she moves throughout the world. So her installation was to include a literal cow brain that was preserved with an empty bottle of estrogen and a section of her vape pen that she uses for weed and a few other pills that she takes on a daily basis to showcase all the different things that make up her brain and how this brought her joy because it's a visual manifestation of herself. It's almost a self-portrait and I'm so happy to have that in the gallery because I think it was quite startling for a lot of people to walk in and see a brain in a jar.

Watch Chella Man perform "Constructing My Own Seat at the Table," below.

Photos courtesy of Chella Man

From Your Site Articles

- Chella Man and Kimberly Drew Front GAP's Colorful Campaign ... ›

- Chella Man Signs to IMG - PAPER ›

- Chella Man and Private Policy Launch Ear Jewelry Collection ... ›

Related Articles Around the Web