The Theater Movement Destigmatizing HIV in Black Gay Men

Sep 04, 2019

Around 17 years ago, veteran magazine editor, content curator, and LGBTQ activist Emil Wilbekin contracted HIV. However, with the aid of healthcare advances like PrEP, he is among the millions who can now live healthy, full lives with the diagnosis.

But at the time of Wilbekin's diagnosis circa 2002, almost 1 million adults and children were living with HIV and AIDS in the US. 45,000 of those cases were those who were newly infected with the virus, according to the World Health Organization.

In 2002, though the worst of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (35 million have died worldwide since 1981) was largely on the decline, there remained a social stigma within and outside of queer communities — especially communities of color. Contraction of the virus was more prominent among Black gay men such as Wilbekin, who was 34 at the time. Unfortunately, this statistic remains true, and in recent years, has grown more dire.

The CDC reports that in 2017, 43% of new HIV diagnoses in the US were of Black people, 60 percent of those being gay men. Over a six year period, from 2010 to 2016, the rate of infection increased by 40% for Black gay men between Millennials aged 25 to 34. And in 2016, the CDC released its first-ever "lifetime risk report," which asserted that one in two Black gay men will contract HIV in their lifetimes.

Wilbekin runs an initiative called Native Son, which draws its name inspiration from James Baldwin's seminal work, Notes On a Native Son. The programming he coordinates can be described as an intergenerational movement aimed at bringing together and empowering Black gay men across arts, business, media, fashion, politics, and healthcare sectors.

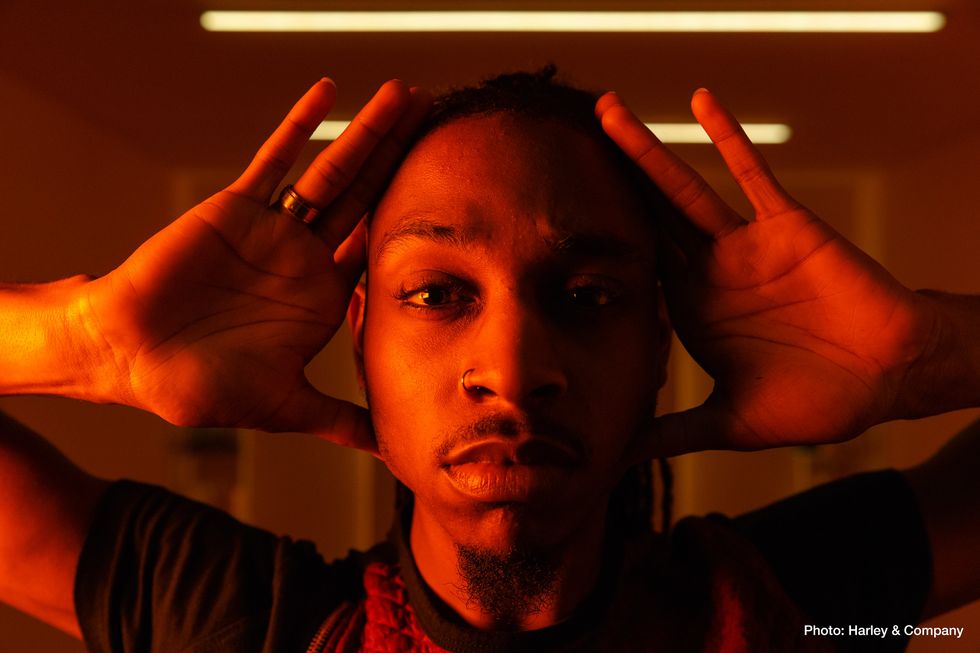

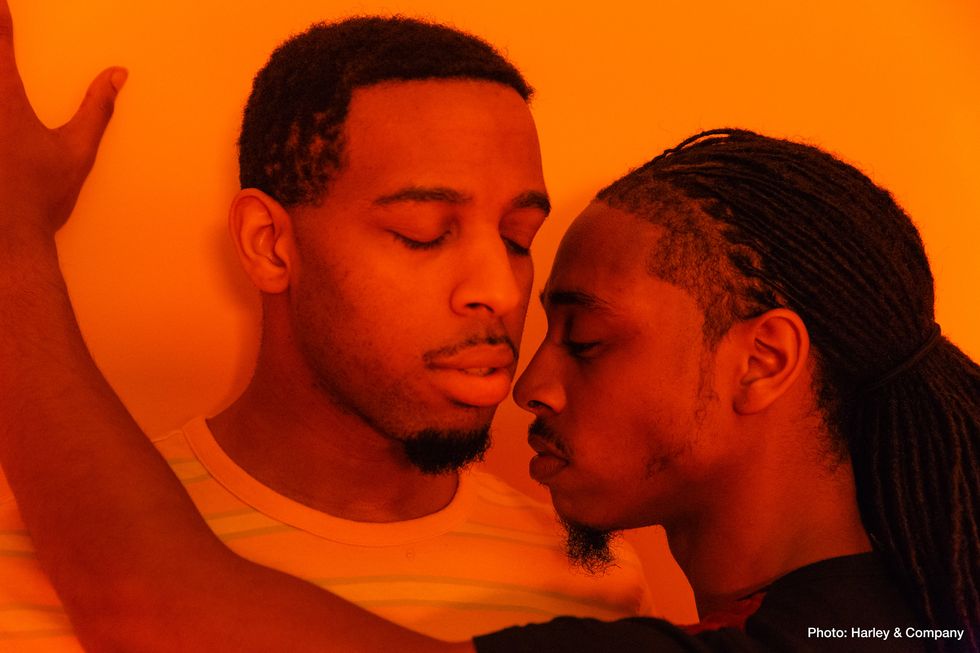

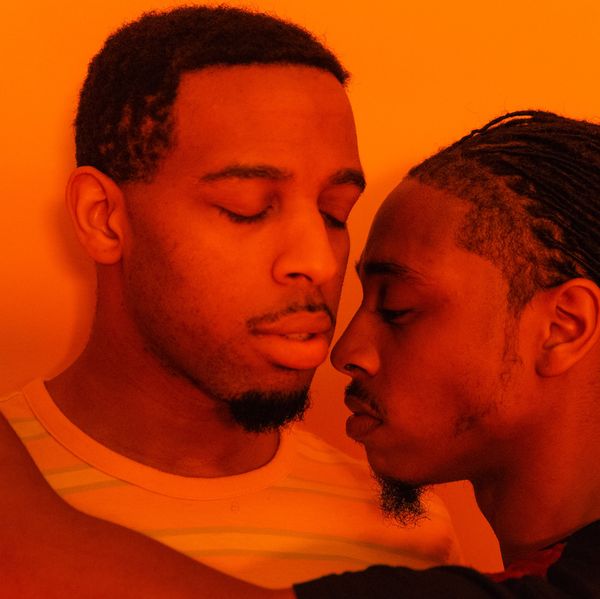

His work made him the perfect partner for As Much As I Can, an immersive theater experience created by Harley & Company, and supported by ViiV Healthcare, that has, like Native Son, become a movement unto itself. They share a common goal of raising HIV/AIDS awareness, and how it continues to impact the lives of young, Black gay men. Principal cast members of As Much As I Can, including Dimitri Moïse, Brandon Gill, and Marquis Johnson share videos about their characters today on PAPER.

As Much As I Can's series of conversation-starting shows began in 2017 with performances in Jackson, Mississippi, and has since been produced in Baltimore, San Diego, and Raleigh. It had its New York debut last year in Harlem, but returns this year with an updated show written by Sarah Hall and directed by James Andrew Walsh. It takes place across 10 performances from September 12-16 at Joe's Pub in Manhattan's East Village. (Tickets here.) Since its start, the show's themes — which tackle stigma, fear, discrimination, and homophobia, whether internalized or externalized, head-on, all factors leading to higher risk for HIV among queer Black communities — have led to eight productions and over 125 performances nationwide.

Wilbekin hopes the show does many things to eliminate these factors, especially if it starts healthier conversations around Black gay men getting tested or taking other preventative treatment measures. One in seven Black people with HIV don't even know they have it. That rate is likely higher among Black gay men, given how they often sit at the epicenter of numerous intersecting vulnerabilities and face a range socioecomic challenges from education down to poverty, as a result.

"At the time of my contracting HIV, I refused to get tested, and it had probably been a year before I really found out, even though I was sick," Wilbekin says. "I didn't want to face it so I took a friend with me. I was disappointed in myself."

Additionally, Wilbekin hopes the show adds to a sense of wholeness among his community. "How do we help heal whatever brokenness or shame lives in young Black gay men, and any other queer people at risk, because there is lack of self-worth within a society that also doesn't value them?" he says. "We have to do better. This is on all of us."

PAPER chatted further with Wilbekin about his work with Native Son, what audiences can learn from As Much As I Can, and self-love.

What led to your involvement with As Much As I Can?

Harley and Company [the show's producers] reached out to me because they read an article where I was interviewed about Native Son. I'm a Black gay man who is HIV+, and Native Son focuses on community outreach and empowering and educating people about HIV and AIDS in the Black community. So when they showed me the trailer for the play, I got choked up and started weeping because it also for me was a sign and affirmation that the work I was doing with Native Son was on point, and had a real need, a real community purpose. So it kind of actualized my dream.

Had you doubted that before?

I knew that there was a purpose and a need for Native Son, but I didn't realize it was connected in this way. Seeing the trailer was like seeing a moving image of my vision. Seeing Black gay men talk about HIV and AIDS in a theatrical space and medium really brought it to life. I think one of the biggest reasons that I was called to create this movement with Native Son was because I wanted to carve out a space for us to see each other, where we can see the beauty in each other, see the value in each other and see it in ourselves as a reflection. So this movement is not about me, this movement is about our community and Black gay men. With HIV rates still rising, how do we as Black gay men love each other, take care of each other, affirm each other, and see each other?

"With HIV rates still rising, how do we as Black gay men love each other, take care of each other, affirm each other, and see each other?"

There remains a general idea that HIV is "over," but this isn't the case throughout the world, and especially for Black gay men in the U.S. Rates of infection have risen steadily in recent years despite the availability of preventative drugs like PrEP.

Yes. As Much As I Can is important, because Black gay men have the highest HIV and AIDS infection rates in the United States and are followed by Black women. So there is a real need to have conversation around this topic because there are so many Millennials are still contracting HIV in 2019. There are medications to prevent that, there's tons of safe sex practices that people can do, but the numbers are still increasing. The CDC is saying that by 2020, 1 in 2 black gay men will have contracted HIV in their lifetime. That's terrifying to me.

What do you think it is about our current system, be it sexual education or healthcare access, that has allowed for this to be the case?

Part of the challenge here is that Black men in general are not valued in our communities. There remains increased rates of incarceration, homicide, police brutality, and early death rates. For some, when it comes to Black gay men, the rationale is, Why would you want to take care of a community that is suffering from HIV and AIDS in numbers that are equal to what it was like in the late 80s and the late 90s? By comparison, when you look at the infection rates of white gay men, they are much smaller and have slowed down. I think part of the reason why we continue to be affected is government, part of it is the pharmaceutical industry, and I think an unspoken part of it really is an issue around whether or not we care about Black people.

For some queer people of color, the process of seeking proper healthcare is a barrier in itself, due to a person's resources, whether it is financial or educational. Information is available, but not always easy to understand or access.

In most countries in Europe, there are amazing healthcare benefits in place for citizens. In the United States, healthcare is overly complicated and doesn't seek to serve everyone and their needs. To that end, the government is actually failing our community. Sometimes people go to the doctor and they feel that they don't know what the doctors are talking about, or they don't trust the healthcare system, they feel like they're being charged every time they go in, so financial barriers are an issue. And because quality care is so expensive, the idea of having to go and get tested and then having to go twice a year to get blood work and medication; those things for many people, especially for marginalized people, is scary. Also, I think it's kind of a known thing in the Black community, but are we accepting of young black non-binary people and allowing them to feel safe and allowing them feel that they can be taken care of, and that they can trust doctors and healthcare professionals? One thing I hope As Much As I Can opens up is exploring how we have real conversations in the community about these issues and destigmatize homosexuality, queerness, non-binary relationships and roles. I also want to break down barriers of communication in families and the church, and even just on the block.

Who do you think is the main audience for As Much As I Can? Who do you think stands to gain the most out of this play?

I think what's great about the show is that it is universal and it's humanity and storytelling. For Black gay men, the power of it opens up dialogue and validates their experiences. The other audience are allies, cis gender men and women and families who maybe their relative is gay, or brother, sister, uncle, father whoever, and they can actually understand what Black gay men specifically go through in their coming out as they're dealing with their own sexual identity and dealing with the same stigmas that then comes from HIV and AIDS. This show is for anyone who wants — or better yet, needs — to bridge those gaps. And it's for Black gay men to discover joy, too, not just sorrow, if only to better love themselves.

As Much As I Can opens September 12 and runs for 10 performances through September 16. Get tickets here.

Photos Courtesy of Harley & Company

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October