Remembering Sylvia Miles, Avant-Garde Actress and Warhol Star

Jun 12, 2019

Sylvia Miles was one of my first celebrities. After graduating college in 1976, I got an office job editing a trash rag called TV Star Parade and somehow I convinced the powers that be that I should do an interview for the mag with Sylvia Miles, not exactly their typical subject. (They specialized in internationally known biggies like Cher and Olivia Newton-John, not New York-based cult figures who'd worked with Andy Warhol.)

The two-time Oscar nominee (for Midnight Cowboy and Farewell, My Lovely) was both an avant garde actress and a gossip column fixture, having appeared in Warhol's Heat, as well as becoming a regular at the sizzling disco du jour, Studio 54. She even famously dumped a plate of pasta on critic John Simon's head after he wrote that she was a gatecrasher; Sylvia said she was always invited, thank you! At this point, I didn't even know that Sylvia was the original Sally in the pilot for Head of the Family, starring Carl Reiner as Rob Petrie. They ended up recasting the entire series, making it The Dick Van Dyke Show, and getting Rose Marie for the part of Sally — I guess this time, Sylvia wasn't invited.

For our interview, I took her to the lunching hotspot the Russian Tea Room, the site of an apocryphal Sylvia story. (A waiter allegedly asked, "How do you like your coffee, Miss Miles?" Sylvia saucily replied, "Like I like my men." The waiter shot back: "Sorry, we don't serve gay coffee.") She was luminous and sexy and fun, with a New Yawk accent and buckets of charisma. I also enjoyed her campy style, which usually included a cacophony of leather and zebra prints, all warring with each other. We became friends, and I ended up accompanying her to all sorts of hotspots, this being the person about whom it was quipped, "She'd go to the opening of an envelope."

She was a feisty soul who came to personally represent the idiosyncratic sparkle of our city at night in the '70s and '80s — and her smoky laugh could light up a room.

Some of the parties were better than others, especially when I went with Sylvia to the dazzling Studio 54, which was a young Brooklyn guy's dream come true, except that — I have to tell the truth — I became demystified of the glamour very quickly as my eyes shot wide open. Sylvia's main purpose in being at a nightclub, in addition to getting photographed, was to track down directors and producers and tirelessly harangue them for jobs. She would actually traipse through 54 looking for show biz folks she could barrel up to and screech "Hire me!" I started feeling like I was Joe, the writer owned by the demanding Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard (though there was no sex in this case).

I also had to roll my eyes a bit when she'd give me holiday gifts based on her own career. A signed Playbill of a show she'd done in London wasn't exactly what I'd asked Santa for, though I eventually came to appreciate it. But even though we parted ways as companions, we remained cordial, and I always admired Sylvia's acting style and star quality. I also came to understand the ways the business pumps insecurity into women like Sylvia, who shaved a bunch of years off her age to try to stay in the game. And amazingly, her constant nudging did result in jobs, as she went from movies — Wall Street, She-Devil — to a soap opera and even wrote a column in the Soho Weekly News for a while, detailing her exploits in the fame game.

And she was usually the highlight of any movie she was in. (Who can forget her Midnight Cowboy performance as a woman who hooks up with hustler Joe Buck — Jon Voight — and is horrified to learn she has to pay him?) She was divorced from radio personality Ted Brown, and must have used the alimony to live in her Central Park South apartment, though the place was cluttered with knick knacks and memorabilia from her career and gift bags, plus a life-sized cutout of rocker Rod Stewart. Sylvia welcomed you there, but forbade visitors to touch anything — especially Rod.

The business played such tricks on Sylvia that she suffered from that weird show biz syndrome of craving attention, then bristling when she got it. When a friend of a friend of mine asked her for an autograph, she almost ate him alive. But she exhibited incredible patience when I'd poke fun of her in my columns, realizing that my obsession with her antics reflected her importance as a NYC figure. She also got back at me — for God knows what—by promising to mention me in one of her shows and then refusing to do so, which I found perversely amusing.

She was a feisty soul who came to personally represent the idiosyncratic sparkle of our city at night in the '70s and '80s — and her smoky laugh could light up a room. One of my funniest memories of Sylvia was taking her to a 1982 screening of Sophie's Choice, in which it was quite clear that Meryl Streep had to decide which of her two kids to give to the Nazis. But the hush in the theater was broken when Sylvia leaned into me and loudly asked, "SO WHAT IS SOPHIE'S CHOICE ANYWAY?" I tried to quietly explain the obvious, then bit my tongue as everyone shushed us — though I guffawed inwardly for the rest of the movie.

When Sylvia stopped turning up at parties, I knew something was wrong. She had been everywhere and then suddenly she was homebound and watching TV, also hanging out in the lobby of her building a lot and driving the doormen crazy. Thanks to another Warhol star, Geraldine Smith, Sylvia had just gotten cast as my mother in Eric Rivas's film Japanese Borscht, literally last week. (Geraldine plays my sister in the film.) I instructed Rivas on how to treat her: "Don't put curse words in the script, make her lines short and manageable, do not have her character dying, and treat her like the star she is. Flatter her!"

Sylvia was a true original and a wonderful actor and presence. I toast her with some gay coffee.

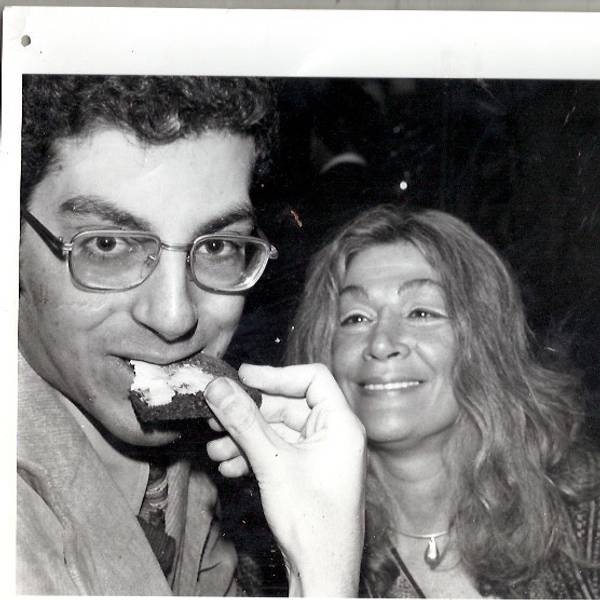

Photo courtesy of Michael Musto

MORE ON PAPER

ICONOS: Pepe Aguilar, El Oficio del Tiempo, la Voz del Silencio y el Peso del Legado

Español

Jan 19, 2026

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October

Entertainment

Matthew McConaughey Found His Rhythm

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

30 September