In Chelsea, an unprecedented art exhibit is showcasing works exclusively by formerly incarcerated artists drawing attention to the U.S. prison system — which currently has the disgraceful honor of housing the largest prison population in the world. Inspired and sponsored by HBO Films' new drama, O.G., The O.G. Experience art exhibit picks up where the film leaves off, by telling the stories of individuals affected by the penal system and uncovering the dark history of U.S. justice system, including the racially biased "war on drugs," the exploitative bail bond system and the legacy of the slave trade.

Though renewed attention has been placed on the human rights issue of mass incarceration, we've only begun to scratch the surface to understand the damage that's been done to communities and individuals affected by it. Policy change will only happen when the people demand it; The O.G. Experience and other initiatives like it aim to highlight the human element of an otherwise callous and cruel system that needs our sustained effort to change.

Two artists involved in creating and curating the show, Russell Craig and Jesse Krimes, told their stories to PAPER, below:

Russell Craig, The O.G. Experience Co-Chair and Featured Artist

I would say I was 7 years old was when I first took to art. I was a foster kid, so I would do art and just be in my own world. It was funny, when I went to prison it was like the same thing — the loneliness of being without a family in a foster home setting. I was influenced by cartoons and Marvel comics, the Simpsons, drawing things from magazines. Those are my earliest memories of my art.

In prison it was an escape and an outlet. There's no other way to put it. It was a focus that took you out of your predicament and put you elsewhere — a concentration that I couldn't find anywhere else. I wasn't interested in a lot of things guys were interested in. I would dabble in playing basketball and playing cards here and there, but the mass majority of the time I spent with the art because it was that escape, that focus. I was teaching myself this thing because I had an interest, and my skill set grew with the practice. My development improved by just day to day. I would just keep pushing, keep trying new things and discovering new things art related.

"I realized that that if I could survive in here — which was like the worst predicament ever— off art, then I could survive out in the world."

I was all self-taught. Any resources or support were from guys on the inside, because it was them who bought portraits off of me which kept me alive, because I was never getting visits or money in the books or support from anyone else. As I said, I was a foster kid, so I didn't have family structure and so that's just how I survived. It also made it more important to get good at the artwork, and that's when I realized that that if I could survive in here — which was like the worst predicament ever— off art, then I could survive out in the world. I started to begin to believe in that, and then when I got out I kept pursuing it. Things are very good, very good now.

Will Smith has this movie, The Pursuit of Happyness and he explains that there is no plan B, there is only a plan A. If you have a plan B, that means you'll accept failure and just go to the easy route, so when I heard him say that, I was like, that's exactly how I was. It was going to be art or nothing. Art or die. How some say skate or die; I say art or die. I was following my passion without any alternatives, so it worked out. I put my all into it. I didn't even think about failure or even when things would be rough, I didn't see it as rough. I saw it as just, life. There was never no strong doubt. I was always just like, "I'm gonna do this."

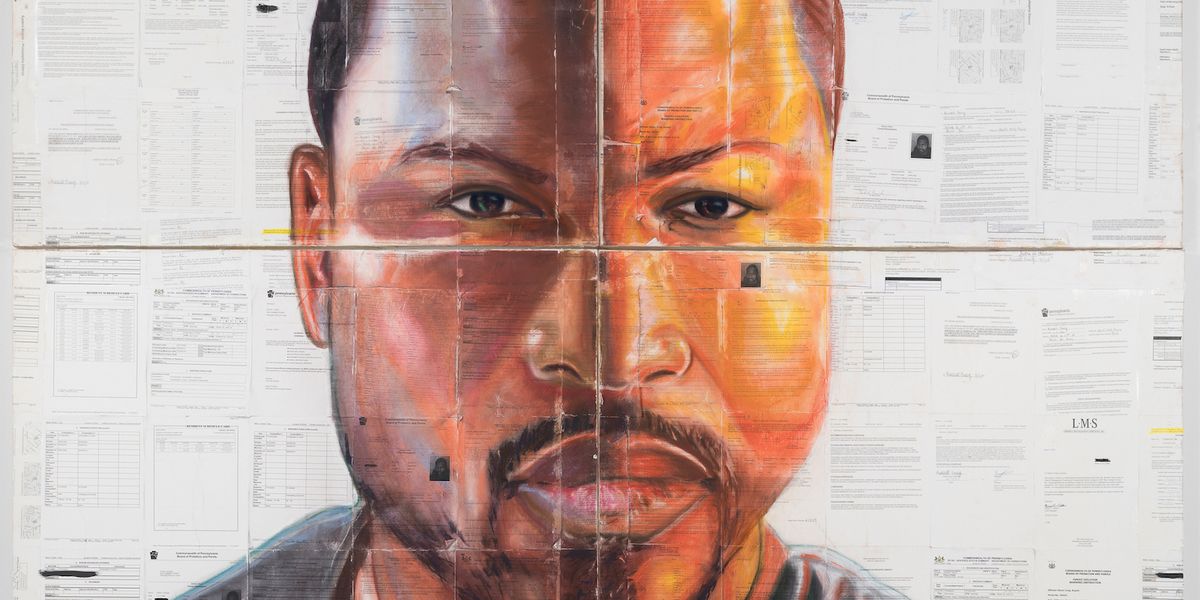

My one piece that's in this show, my self-portrait, speak about the stigma of being a criminal and being labeled that no matter what, even though I'm a different person now. That part of me is supposed to be behind me, and that's exactly the piece that I explain to people — the pastel is transparent for the writing that was on my prison documents. It still comes through — the writing, the charges of my papers— and it symbolizes that stigma that stays with me even though I've moved on to be someone else. I served my time, supposedly, but people still see me as that.

I've found community in people who understand, whether they've had the experience or people that are activists and actors — whoever they may be that have an understanding about it. The art has a meaning that's beyond myself. It's like I have a duty.

I have no choice but to pay attention to criminal justice reform because I'm of it. There are people involved who are getting all this attention and popularity for it. To a degree it's good for that, and hopefully will bring change. But there are people that aren't really true that are entering the space, so that's a bad part of it. But there's always a bad side to things. Like I said, it's our duty to keep it real and keep it pushing. You just have to work even harder to keep things authentic. False stuff comes to light, you just have to keep being more creative and expressing issues that need to be brought to the front.

Jesse told me about this vision a long time ago, so he is the main brain behind it and it's just amazing. He does his homework on other artists. He believed in me; he used to tell me that I was more talented than I could realize. He did that with other artists too, he would study them and find people far across the country to put the work together. It's just an amazing collective of artists. We aren't just boosting ourselves; we put it out there for the people to see and we've been getting good feedback because the work is good, smart. It's just a wonderful opportunity to be a part of it.

Jesse Krimes, The O.G. Experience Co-curator and Featured Artist

For the past four years I've worked with the Soze Agency. Through them I was asked to help co-curate this exhibition, and part of that is because myself and Russell helped co-found a fellowship program with them called the Right of Return USA. Through that fellowship program we support formerly incarcerated artists from across the country with $20,000 grants, and through that application process we came across so many incredibly talented artists that we can't fund. So when this exhibition opportunity came up, we had this extensive list of artists from across the country that we were really excited to include.

Art has always been integral to my life. I grew up pretty poor with a single mother, 16 years old, no father. Lot of other life things that happened. So artwork was always a way for me to have a safe space to create and express myself. I ended up going to school for art and graduated with my BA in art. Then I got indicted, and so art has always been a natural part of my life. It was never anything I really questioned. Then when I ended up going into the prison system, it again provided that space for me to invest myself in that meaningful way under some pretty dire circumstances.

The transition from focusing on my own work as an artist to someone who also uplifts other artists began to solidify for me initially was when I was incarcerated. I just saw all of the incredible raw talent that a lot of people had, because of the same way I started creating art, a lot of people in there do that as well, and for many of the same reasons. When I became aware of all these amazing artists, I started teaching art in there to start develop some more conceptual, critical rigor within their works. I also started organizing some exhibitions on the outside with some friends I still had who would help me display some of the works we created inside, outside. It comes from a place of being in the system and seeing people who have been thrown away and completely disregarded by society, which really made me angry and created this fire in me. I'm not unique, I'm not exceptional, and there are thousands of other people just like me who are just as equally deserving of this platform. That's kind of what drove me to do that when I was in and what is driving me to do that now: to create this space for other artists to control their own narrative.

"It comes from a place of being in the system and seeing people who have been thrown away and completely disregarded by society, which really made me angry and created this fire in me."

It was completely something we had to do on our own, well I had to do on my own. That's why a lot of works you see are using materials and processes that are very — you have to be very creative in how you use materials and create the artwork because there is such a lack in availability of programming and materials and other things to invest yourself in. A lot of it is just sheer force of will to create.

For the specific purposes of what we are capable of, the main thing that we look for are artists who are exceptionally talented and gifted within their craft, but also artists who have a critical perspective and understanding of how their work is engaged in issues of criminal justice reform. It's one thing to be an incredibly gifted artist, and it's another thing to understand how your artwork fits within these larger narratives that can be used for the purpose of creating empathy or changing the prevailing narrative or galvanizing an audience into action. We like to support artists who are very intentionally creating artwork for socially engaged purposes.

Honestly, it has been pretty revolutionary in terms of the responses that I've been getting personally which is that — I just don't think a lot of people in the country in general are aware of the incredible amount of talent and critical rigor that a lot of these artists are making, and how engaged they are in this work in criminal justice reform. The feedback I've been getting has been incredibly positive and insightful. It lets me know that providing this platform and allowing people to talk about their own lived experience is already having an impact on the audiences, and opening people's perceptions to how we can include to people who have that lived experience in a more meaningful way.

There are days when I feel like we make some incredibly significant progress. And then at the same time, I have to keep a realistic view on the fact that we still have far too many people in prison, and far too many people on supervision. In many ways there's a lot more visibility, and people who have the lived experience are getting more opportunities to be engaged in those conversations. But we are still very, very far away from where I would like the conversations to be. We're talking about prison reform, but there are a whole other set of issues that feed into mass incarceration that are pre-incarceration, that are post-incarceration. How do we get to a place where the narratives we're having envision a world where we don't have to rely on punishment as a form of addressing a lot of these other economic and social issues that are going on in our country? It's a fact that punishment is not corrective.

Immediately after this I'm creating a project in a rural part of Pennsylvania, where I'm building a barn in the center of a corn maze with members of the Amish community along with formerly incarcerated people, the mayor and the district attorney's office, and the police department. I've been doing workshops with all of these different system actors and formerly incarcerated people, and the basic idea is to create this similar kind of project that's being displayed here in New York, but figuring out another way to have these conversations with parts of the country that would never come to New York to see an exhibition. How do we engage people in conversations that are outside of our bubble? It's a very important time to figure out ways to engage those communities, because they're reachable but I feel like they've been left out of these conversations in any meaningful type of way.

The main core of the exhibition is being able to provide a platform for other artists. That's the most important takeaway from this that I hope people leave the exhibition with.

"The O.G. Experience" is free and open to the public in New York City through February 25. See pictures of opening night below:

Photography by Kisha Bari