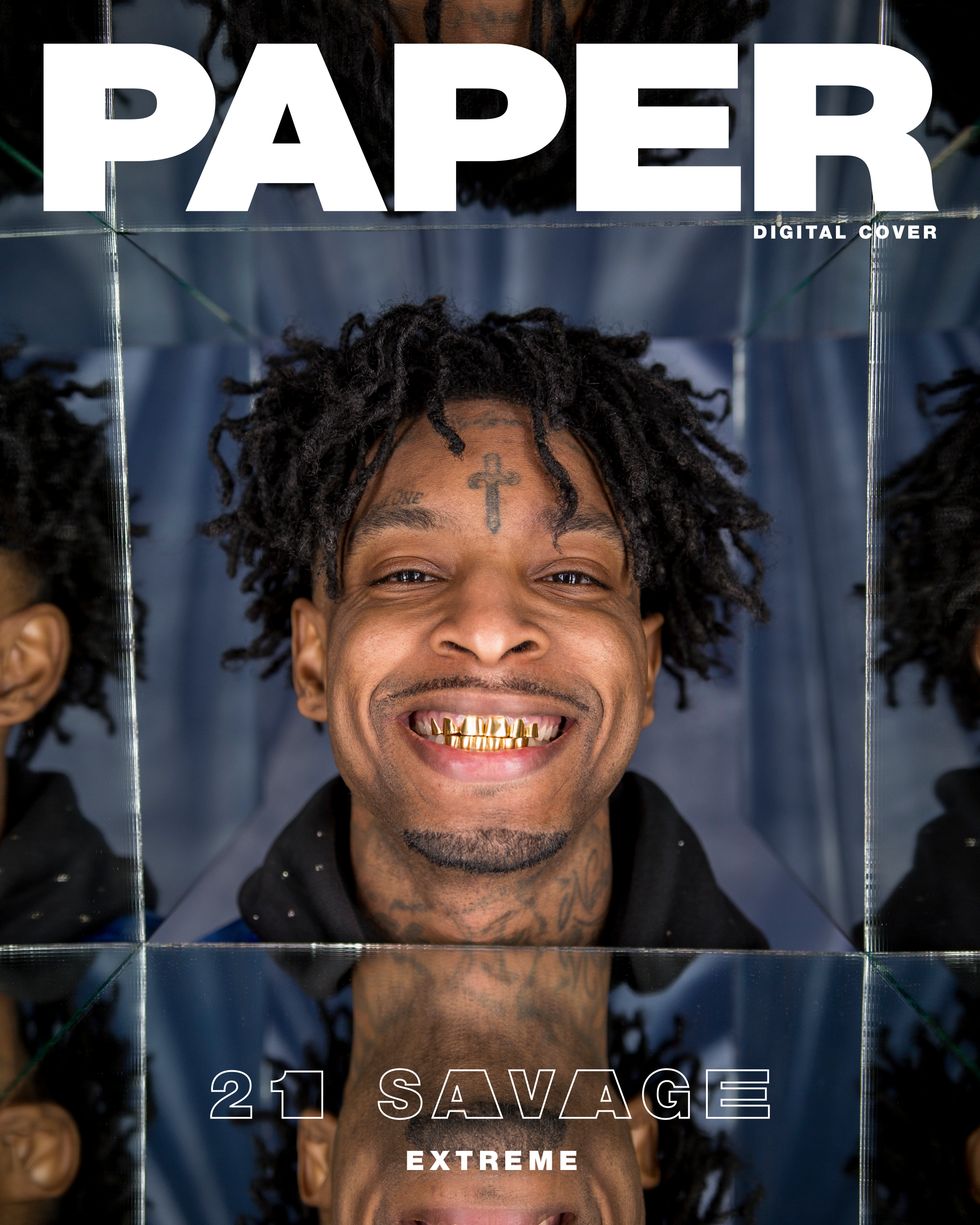

Extreme

Don't Stop Talking About 21 Savage

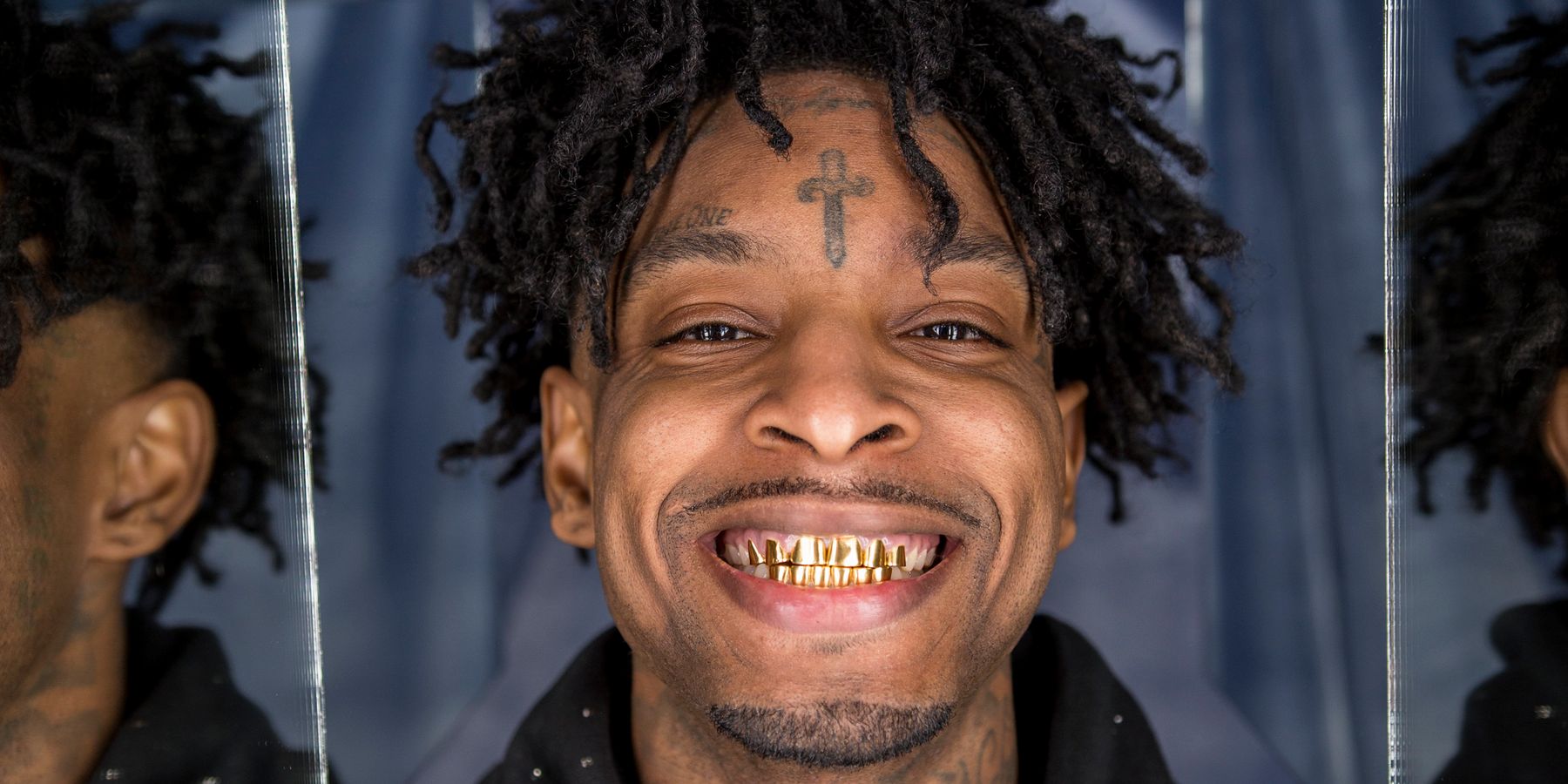

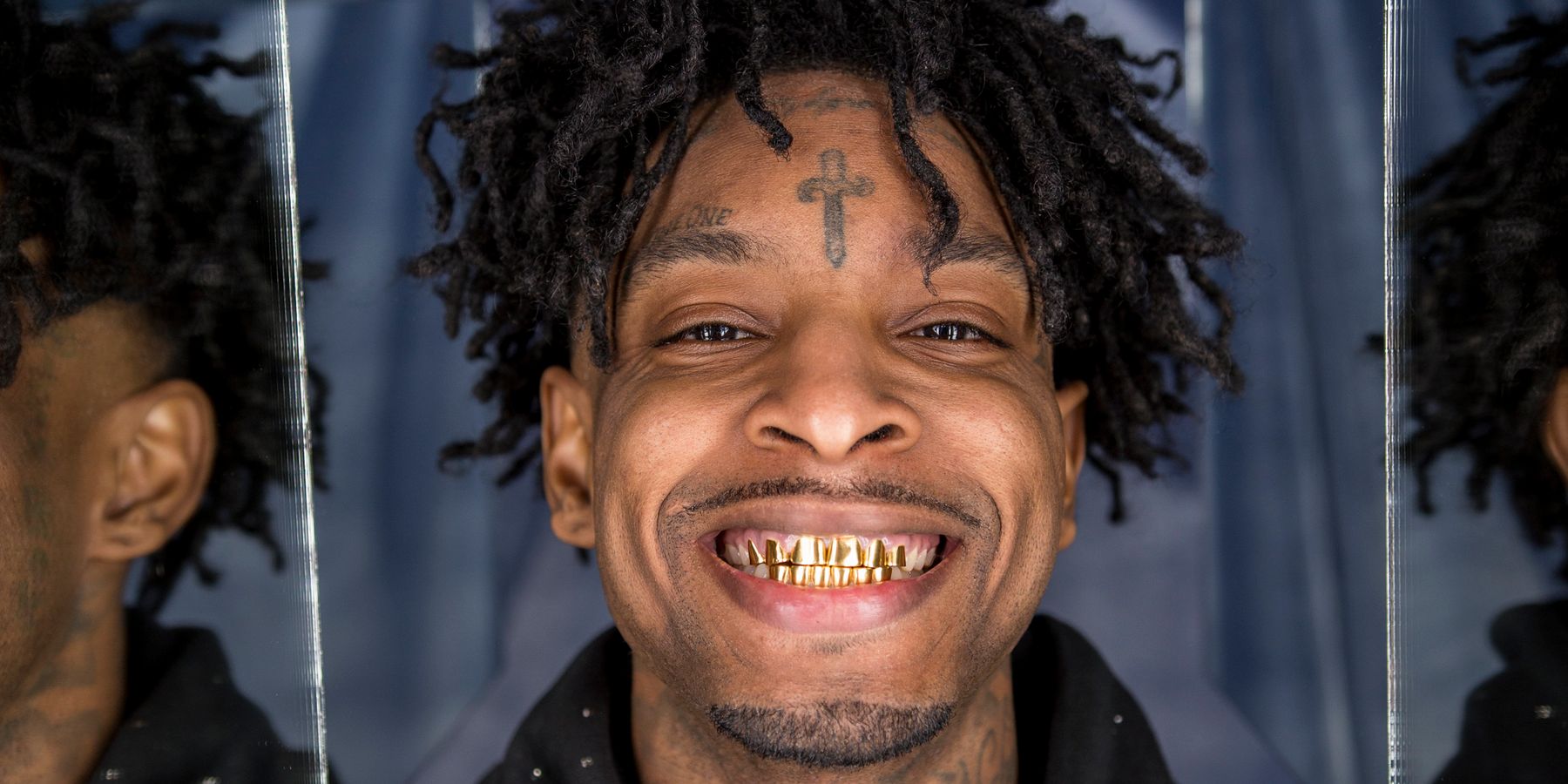

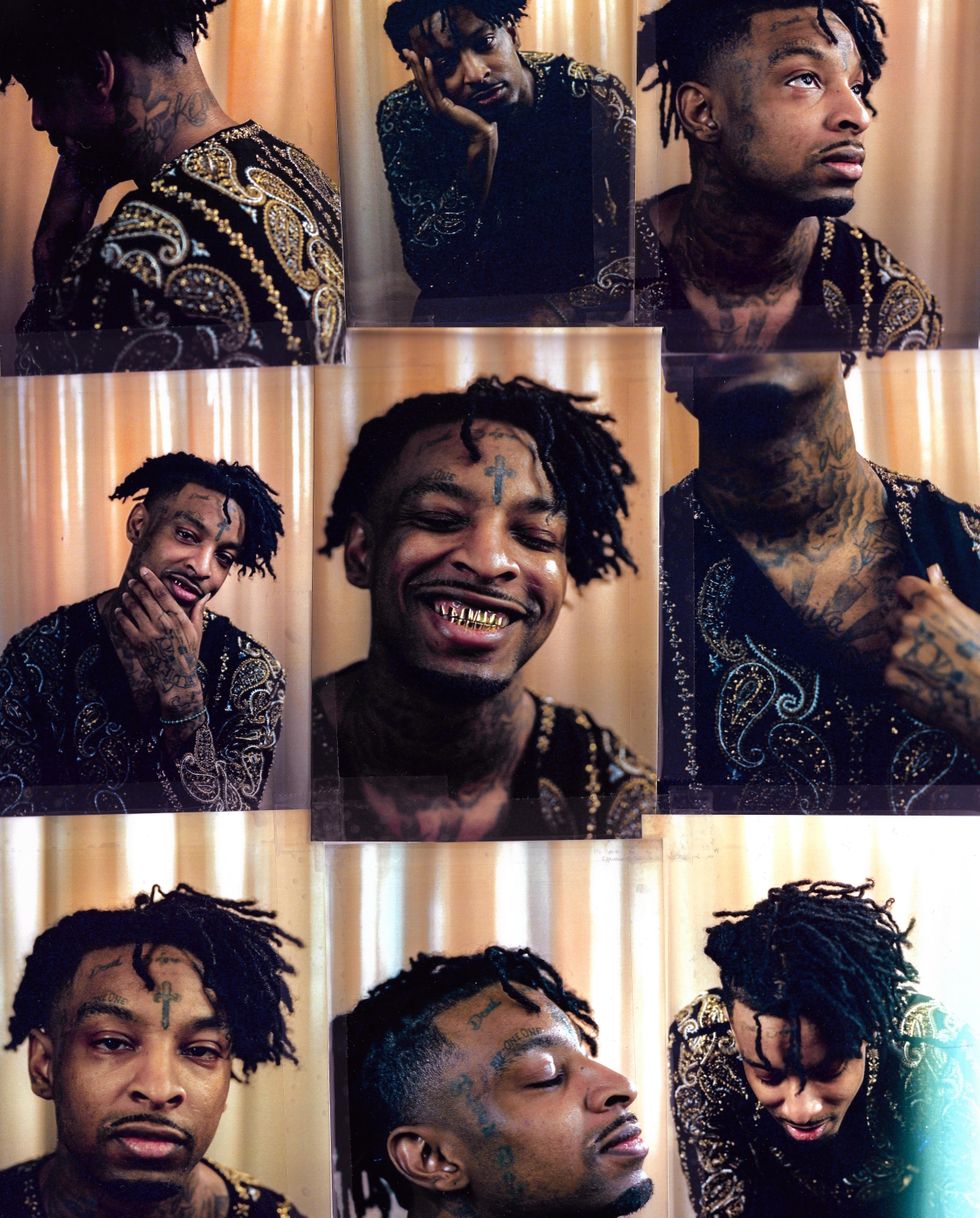

Story by Stephanie Smith-Strickland / Photography by Alex G. Harper / Styling by Sue Choi

10 June 2019

Existing as a Black person in America has always been complicated. The pain and triumph of history can feel as if they are imprinted into the very bones that are our substructure. Perhaps that is why when we gather in close quarters we theorize about these histories. Whether conspiratorial or evidence-supported, the act of conversation is a balm, a way to unpack terrifying realities and to make sense of the senseless, the brutal or the unjust. Hip-hop artist 21 Savage isn't known for being particularly verbose, but has become central to increasing dialogues about Black immigrant experiences. Yet as he perches on a wire-frame chair in a downtown LA studio awaiting the arrival of his barber, it would appear the entire world exists solely on his phone.

Two hours later, not much has changed. He's still putting the iPhone's endless scroll function to exemplary use, but the arrival of food seems to perk him up a bit — that, and a long-awaited haircut.

Related | Bad Bunny Just Hits Different

In front of the camera, he displays the same quiet intensity present in lyrics that vacillate between tales of paranoia and redemption. His features are schooled into an expression that could be apathetic, or perhaps merely guarded, depending on who is looking and what they want to see. In light of his February 3 detainment by ICE, the who that is looking and what they want to see have become central to the rapper's still-unfolding story.

Full Look: Off-White

For some, he has become a beacon of hope and an example of how violently and suddenly life can change for the estimated 11.4 million undocumented immigrants in America. For another subset of the country, he is the "bad hombre," the criminal ghoul lurking uninvited in Trump's America. Following 21's arrest, ICE spokesperson Bryan Cox claimed that in addition to violating federal immigration law, the rapper was a convicted felon who had faced federal drug charges. Shortly after, 21's legal team contested his felony status in a public statement. "Mr. Abraham-Joseph has no criminal convictions or charges under state or federal law and is free to seek relief from removal in immigration court. ICE provided incorrect information to the press when it claimed he had a criminal conviction," they said.

Neither the hero nor the villain narrative take into account the human being, a 26-year-old aviation enthusiast (he is working toward getting a pilot's license, an extension of his elementary school dream of joining the Air Force) and father of three, whose life has been equally defined by circumstance and chance.

21 Savage was born She'yaa Bin Abraham-Joseph on October 22, 1992, in Plaistow in Newham, East London. When he was seven, he and his siblings relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, with their mother following behind them after separating from his father.

Full Look: Louis Vuitton

Life in Atlanta, though far from idyllic, was the bedrock of 21's identity, and up until his detainment, it is where most of the world believed he was born. At the very least, it is where the persona of 21 Savage first took root. According to an interview 21 gave to the FADER, by seventh grade he had been banned from the DeKalb County School District for gun possession after he brought a firearm to school in response to threats from another student. By the time he was a teenager, he was spending the majority of his time in the streets as a Bloods-affiliated gang member.

In 2013, on his 21st birthday, he was shot six times and his best friend was murdered in the encounter. But he reflects on the situation with resilience: "I stay focused on moving forward and not letting stuff put me in a hole or make me feel depressed. I don't really dwell, but I think about the people I've lost. At the same time, I think of the moments I had with them versus them not being there."

Top: Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello

Still, in songs like "Numb," which appears on his 2017 studio debut, Issa Album, he finds space to mull over how early proximity to violence shaped him. "Nigga when they killed my brother, I had to go hard / Put that chopper in his face and then I Bogart / Niggas tryna cross me, I don't understand it / I'm just tryna take care of the family," he raps.

Other efforts, like "Real Nigga" from his 2016 EP Savage Mode or "Gun Smoke," which appears on his second studio album, I Am > I Was, lean into tropes about street life, at times even celebrating the most violent aspects of 21's experiences. Even in these moments, his music tends to return to one driving force: necessity, underpinning how socioeconomic disparity and disenfranchisement are a catalyst for crime.

Full Look: Louis Vuitton

While his undocumented status might have cast the musician as an unlikely champion for immigration reform, there is value in the fact that his life has not been a case study in the model immigrant narrative. All too often, the mentality around immigration hinges on whether a newcomer lives life as a "model citizen." For instance, the story of Emmanuel Mensah, a Ghanaian immigrant who died saving his neighbors during a fire in the Bronx last year, sparked conversation about how valuable immigrants are to America.

Mensah's actions were heroic, but his worth as a human being should never have been tied into the sacrifice of his life. That we see stories from people like 21 Savage — who is fortunate enough to have amassed the wealth and platform to fight deportation — is important. For thousands of others, who lack the financial ability to hire lawyers who can navigate the murky waters of immigration law, their lot falls to the mercy of a historically biased system.

Full Look: Off-White

Even the core of 21's citizenship issue appears to be centered around a misunderstanding. Although 21 Savage and his legal team declined to discuss specifics of his status and case, the rapper told The New York Times that in 2005 when he was 12 he returned to the UK for a month to attend his uncle's funeral. Upon re-entry to the United States he was granted an H-4 visa. An H-4 visa is given to the partner or the children (under the age of 21) of an H-1B visa holder. "An H-1B visa is for a professional occupation and will usually go to someone who possesses a degree that is the normal entry qualification for that profession," explains New York-based immigration lawyer Andrew L. Fair (Fair is not part of 21 Savage's legal team). "Usually the H-4 visa will expire at the same time as the H-1B visa holder, though it might be possible that it could expire sooner," he continues.

Related | Seeing Red: Zendaya to the Extreme

According to ICE officials, 21's visa allegedly did expire sooner; the next year, in 2006 to be exact. What remains unclear is why his visa status would have changed if the attached non-dependent visa had indeed remained valid. "If the H-4 visa holder is from a different country than the H-1B visa holder and is subject to time limitations due to reciprocity, then it's possible that may occur," Fair says of what may have happened (although, again, 21 and his team declined to clarify the particulars of his situation).

Full Look: Louis Vuitton

The rapper had been actively trying to rectify his immigration status since 2017, when, according to a comment one of his lawyers made in an earlier interview, he allegedly applied for a U visa, something typically issued to those who have either been the victim of a violent crime or of aid to law enforcement while in the US. Therein lies the discrepancy.

"It seems to me that if you are [eligible for deportation] for having been convicted of a crime, you wouldn't be eligible for a U visa," Fair assesses, of Cox's statement. If 21's U visa application is indeed pending, then Cox's portrayal of him as a convicted felon would indicate either an exaggeration on the part of ICE, or that its infrastructure is so convoluted even the people who work there are confused.

Full Look: Off-White

In the meantime, the threat of potential deportation still looms, and with family separation scandals dominating the news, 21's plight has struck a chord. "I didn't see my kids for almost two weeks," 21 says of his time in detainment. "There are people in detention centers just sitting for months and even years not being able to see their families. Then some of those people just end up being sent off overnight to a place they ain't never really lived and they don't ever see their family after that."

Within this discourse, the stories of Black immigrants have still largely remained in the background, with the public targeting of Hispanic immigrants and immigrants from Muslim countries dominating media coverage. Part of what makes 21 Savage's case so unique is that it brought these stories to light, but also underscored how race plays a major role in the reality of Black immigrants. Even in the pursuit of the "American Dream," they must grapple with an unasked-for American inheritance, one rooted in a messy racial history that has been playing out in increasingly divisive rhetoric and policies that criminalize Black immigrants at disproportionate rates. A 2016 report published by the NYU Immigrant Rights Clinic and the Black Alliance for Just Immigration found that Black immigrants account for only 7% of the non-citizen population, but about 20% of all immigrants facing deportation. Much of this comes down to how racial bias weighs into the day-to-day policing and arrests of Black people in general, which only makes Black immigrants doubly vulnerable to deportation.

Full Look: Louis Vuitton

21 wasn't aware of these statistics growing up, but being aware of his status made him innately distrustful of the system. "I didn't know all the specifics; I just knew if the government finds out your paperwork ain't all the way straight they ship you out."

Starting the process doesn't necessarily make things easier, either. Situations ranging from job on-boarding to getting a driver's license or financial aid require documents that could expose the status of undocumented individuals. "My situation made me realize I was different. All of my friends were getting their driver's licenses and getting jobs and I couldn't do any of that, so I had to get creative."

Full Look: Louis Vuitton

His inability to find legal employment brings up another hurdle faced by Black immigrants: America's racial wealth divide, which is only growing larger by the year. A 2007 Princeton survey found that 40% of African immigrants (this doesn't even take into account the rest of the Black diaspora) had completed four or more years of college while only 20% of white Americans held bachelor's degrees. In spite of that, the median average income for African immigrants with degrees was $44,000. The national median salary was just over $50,000, and the median average for white Americans with bachelor's degrees was $60,000.

If the reality for "educated," documented immigrants is near-unlivable wages, imagine the reality for someone undocumented. The perseverance of 21 is also representative of many other immigrant stories. Despite being unable to find legal work, he persevered and made music — something that began as a hobby — a viable and lucrative career.

Full Look: Off-White

While rappers like the late Nipsey Hussle considered how disenfranchisement impacts Black communities, few have actually taken the steps to implement change. Where Nipsey focused on real estate and "buying back the block," 21 launched The Bank Account Campaign on the heels of his 2017 charting single "Bank Account." A collaboration with non-profits Juma and Get Schooled, the initiative aims to create jobs for Atlanta youth and teach high school kids financial literacy.

"The goal is creating generational wealth," the rapper shares of the program he hopes to expand into the national school curriculum. "It wasn't until I hired a business manager that I learned about investments and building credit...Kids should be learning that before they get into the real world and make mistakes with their finances."

Even with a legal nightmare to attend to, 21 hasn't stopped giving, living or working for that matter. On May 6, he attended his first Met Gala wearing a gold brocade blazer designed by Harlem icon Dapper Dan. A day later he announced a North American tour in support of I Am > I Was. When asked who he was and who he is now, the rapper's response is expectedly laconic: "I'm somebody who can take care of my people." Whether he's ready to accept the mantle or not, he's also someone whose future in America will impact people far beyond his purview.

Top: Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello

Photographer: Alex Harper

Stylist: Sue Choi

Location: Apex Photo Studios

PA: David Peck