Sally Potter's Smartphone Cinema Provokes 'Rage' 15 Years Later

By Tobias Hess

Mar 05, 2024“Smartphone cinema” could sound to one like an oxymoron, but Sally Potter, the British filmmaker behind such essential works as Orlando, Ginger and Rosa and The Party, does not see the utility in such distinctions. There must be some way, she believes, to merge the syntax of cinema with the ubiquity of the mobile phone.

In 2024, this idea still strikes as provocative, so one can only imagine, though, how such a project would incite cinephile audiences in 2009, just two years after the release of the first iPhone. In Rage, Potter’s 2009 film, the director boldly explored such a question. The first film designed to be watched on a mobile phone (but also able to to be seen on the wide screen), Rage provoked a small moral panic when it premiered in 2009 at the Berlin Film Festival. “The film was treated as a news item rather than an artistic review,” Potter remembers. “There was one headline that said, ‘Sally Potter wants to kill cinema.’ And I thought, ‘This is the great passion of my life!’”

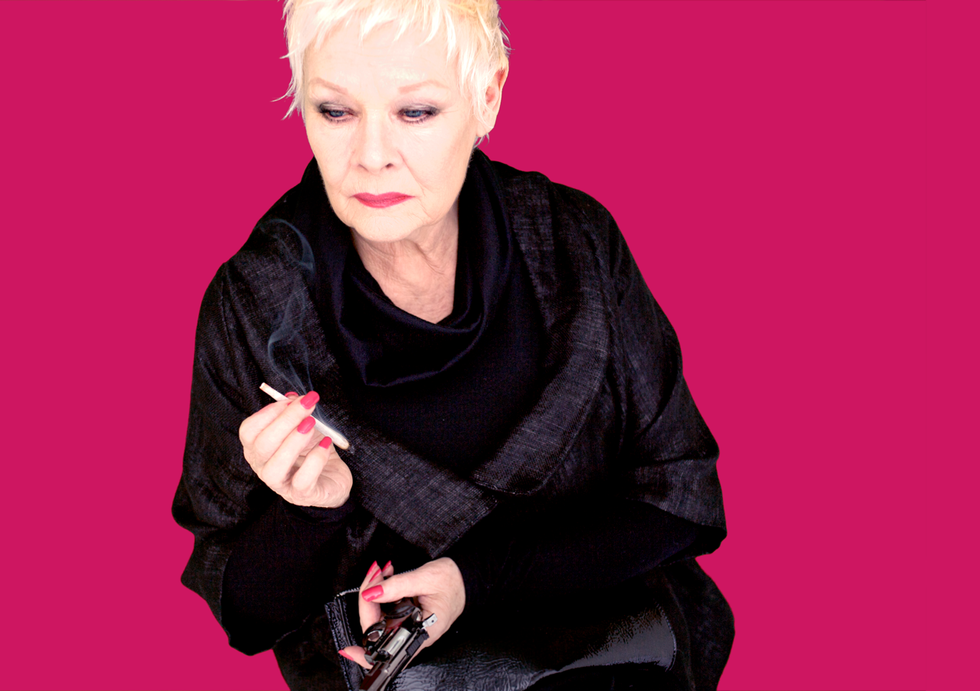

They were provoked, perhaps, by the formal challenge of this film (as being “for” the mobile phone), but also by the experimental format of the film’s narrative: a series of close-up monologues set against bright, single-color backdrops. Via these monologues, the story unfurls over the course of several days at a fashion show, where chaos, and eventually, murder, push the characters to test the limits of their own morality, hubris, greed and paranoia.

“To give narrative information by withholding all imagery, to see nothing except these faces coming and talking against a color: it's almost like a provocation,” says Potter. But it also fits neatly into the narrative framing. The film is conceived to be shot by a young child named Michaelangelo, who, mobile phone in hand (it was actually shot on a handheld camera), interviews the fashion show’s participants with a child’s blind curiosity.

The cast is stellar, and even a bit prophetic regarding the future of Hollywood: it includes the already iconic likes of Judi Dench, Jude Law, Steve Buscemi and Dianne Wiest, along with then-newcomers like David Oyelowo, Riz Ahmed and a pre-Suits Patrick J. Adams. Such a cast, and the truly gripping narrative, should have made Rage a crowd-pleaser, despite its fairly avant-garde format. But, it seems, the film’s essential provocation, and the monologue format, which is ubiquitous today in our age of TikToks and vloggers, was too ahead of its time.

Thankfully, Potter and company recognized that. After seeing the film in New York’s Metrograph theater during a 2023 Potter retrospective, the director decided to give the film another-go, this time on Instagram on TikTok. Breaking down the film into bite-sized Reels and TikToks, Rage is now available to view either piecemeal or in total through its own Instagram page and TikTok account. The question remains, though: is there a life for cinema on the smartphone? Today, due to the device’s overwhelming ubiquity, we are in a much better place to answer such a question.

PAPER chatted with Potter, while she was in the throes of the film’s Instagram premiere, about the film’s initial controversy, facing the chaos of the algorithm, smartphone cinema and unfolding gender roles in film.

Had you thought about re-releasing the film prior? What was your relationship to the film since its release?

[When I made the film], the whole idea was for it to have a sort of multi-platform life and explore what kind of images would work both on a very, very tiny screen and on a big one as well. We wanted to keep a conceptual purity about it and meet the advances in technology head-on, particularly the clearly massive change that we were in the middle of in regards to people's relationship to the internet and to their phones. And so it was a bit disappointing that it couldn't go wider because the technology wasn't there. There weren't enough people who could receive it on their phones at that point. So then, coming back to it [14 years later] and seeing it in New York, it felt so evident that it would be relatively straightforward and easy to [re-release the film on Instagram.]

When it initially came out in Berlin, the film was quite controversial and was received to mixed reviews, which surprises me now because, yes it’s experimental, but the narrative is very gripping, and the performances are so strong. I feel like there'd be an appetite for that. What do you think was going on at that moment?

This isn't new for me. Almost every film that I've done that has broken a conceptual barrier, has been met with a mixture of wild enthusiasm on the one hand and a peculiar kind of rage on the other, given the title. The film was treated as a news item rather than an artistic review. There was one headline that said, “Sally Potter wants to kill cinema.” And I thought, This is the great passion of my life! But I was wanting to embrace the new and discover what was possible with changing forms. I also think that the concept is perhaps closer to an art piece — to give narrative information by withholding all imagery, to see nothing except these faces coming and talking against a color. It's almost like a provocation.

It was ahead of its time technologically, but also formally, because now self-portrait video is essentially the most ubiquitous form on the planet. There are selfie videos, but the film is also akin to confessionals on reality TV.

I was very, very aware of that, and very fascinated by the early days of this kind of explosion of self portraiture. [In Rage], every camera move was at arm's length. I was trying to replicate the selfie distance before there were selfie sticks. It wasn't actually shot on the phone, but the feeling I was invoking came from arm's-length framing and the certain kind of implied narcissism that comes from that.

Speaking of narcissism, the film is set in the fashion world. Did you have a relationship to fashion and the fashion industry prior to this film?

Not really. When I first wrote the script, it was an actual murder mystery set in the fashion world that showed everything. I rewrote it just to trim it down to the most minimal form that I could think of, showing just faces. But I also didn't ever feel it was really about fashion. I felt that it was about the generational divide between the character of Michelangelo, who's growing up in a world with a camera in his hand, and the whole older generation that doesn’t quite know what's going on. I was wanting to explore that divide. And then I wanted to explore the whole performative aspect that happens as soon as you put a camera in people's faces. It's exploded so much since this film was made.

Today, you go to a gig and see people watching the gig, but they’re turning away from what they're watching [and filming a selfie] so they can see their face watching the gig that's behind them. We take these things for granted, but [this sort of behavior felt like] a kind of madness, a kind of aesthetic reversal, a form of uncritical and narcissistic engagement. That's not really to do with fashion, it may have more to do with filmmaking as much as fashion, or, indeed the 15 minutes of fame principle: this kind of lust for celebrity, the sense that people will extinguish if they're not visible. That has exploded in ways that are quite extraordinary.

This is a brilliant cast. How did you engage all of these various, quite famous actors for such an unusual project?

Well, in the way that I always do really, which is to make contact in whatever way is appropriate. I tried to make it an attractive proposition, not just via the character that they would be playing, and the fact that they would be working with the monologue as a form which is both very challenging, but also very exciting, but also that I would only be asking for a day or two of their time.

None of the actors met any of the other actors. I literally worked serially with each person, one on one. They had my full attention, because I was behind the camera at an arm's length. It was intense, but it was short for each actor, so it was not hugely demanding of their time. They certainly weren't going to be making much money out of it, but they were going to have an experience that was extremely unusual. And without exception, the feedback that they gave me at the time was that they loved working that way, stripping everything away down to the performance and the text.

I’d like to address Jude Law in this film. Jude plays a character named Minx, whose gender identity is largely ambiguous in the role, but is certainly femme-presenting. For context, Minx’s demeanor and accent even changes throughout the film, so there are many layers of ambiguity — but I wanted to explore the question of the cis male actor playing an ostensibly trans role. You’ve explored gender and identity deeply in your work and I imagine this would be approached differently today. How are you approaching this question now?

It’s a very familiar and interesting question for me. The way I worked with Jude was not about essential identity, but rather about how this is a person who is moving through performed personas. The character has a Russian accent at times, an American accent at other times. The character would be what one would call genderfluid today, not able to fix and say, “This is what I am now.”

Now, the relationship between who the actor is in their life outside of the film and what they play is more contentious than it was then. But I think that for this notion of somebody performing multiple identities and playing with that: the whole principle of that was to undercut any idea of essentialism, that somebody is, for example, a cis male or female and therefore should only be playing a certain role. The whole idea is to undercut and disrupt that through this Minx persona. It was much more coming out of a drag tradition.

But yes, if I was making this film today, I would be aware that this might be perceived critically. I dealt with this when we were making Orlando. I was attacked from all sides. They said, “You can't have a woman playing a man and a woman,” or, “You've got to have two different people. You've got to have a man playing a man, and a woman playing a woman.” But the argument from Virginia Woolf [who wrote the book Orlando, which the film is based upon] is precisely saying that these [gender distinctions] are now meaningless distinctions, that these are these are roles that we occupy and we build and construct.

Take me through the process of re-editing the film for a new format. What was the experience like reconfiguring the film for the smartphone today?

We tried a bunch of different things, bearing in mind the length of posts on Instagram and TikTok, and how that may relate to the length of the shots in the film, and whether it was necessary to shorten things or compress them. In the end we decided to not do that and stay pretty true to the original shape of the film and make each shot a new post. It's not clear at all how people will interact with it, whether they will watch it as a whole, or they will cherry-pick bits that attract them, watch things out of order. I think I just wanted to leave all of those possibilities open and see what happens. I wanted to see how its syntax would work within the kind of chaotic algorithm of Instagram and TikTok. What will come up on people's feeds?

How are you perceiving the life of the film from here on after?

Re-releases are complex. So it's just a matter of whether it somehow finds its way, and people pick it up for other reasons. Most of my films have continued to have a very long life. They don't really go away; they just crop up, or suddenly there's a kind of revival, or, in the case of something like Orlando, it is never not showing somewhere. I think I'll be intrigued to see what happens with this one. I know what already happened from before. There were a lot of aesthetic imitations of the way the faces were shot. Suddenly, in every magazine, there were people against a plain color background, with this very bold framing. That aesthetic simply wasn't there before. So I noticed how it is fed into the culture. What I haven't seen, however, is people taking something like a feature format into the social media sphere. So I'm going to be very intrigued to see whether the relationship with time is determined by feature length. How it can or possibly translate into something which is as fast moving and immaterial as Instagram or Tiktok. Or whether it can withstand the kind of fragmentation of people absorbing bits rather than the whole, because of the narrative structure. That is all off-screen. There's a lot implied, so you need to follow it narratively to understand what's really going on.

I have one more question. You're essentially posting your film online for free. How do you feel, as an artist who has an ownership over this, giving it away in this fairly radical way?

Well, streaming, for music and a lot of other things, has basically ruined all artists' lives, along with the possibility of any kind of economic survival from our work. And so I've kind of gone along with the notion of just give it all away. You can't fight it, to a certain degree. Obviously we have to find ways to survive, but from an intellectual copyright point of view, I've had my work plagiarized many times over. One can either decide to get very upset and paranoid about it and guard it, or you can decide that your work is there to go out. When I feel my work is ready, I want to put it out. That's the energy. So there's something kind of quite exciting about throwing this film to the wolves: It's yours. Do what you want with it and see what happens. I might live to regret this, but at the moment that's the way I feel about it.

Photos courtesy of Sally Potter/ Adventure Pictures

Related Articles Around the Web

MORE ON PAPER

Entertainment

Dove Cameron and Avan Jogia Broke Their Molds

Photography by Gustavo Chams / Story by Joan Summers

Photography by Gustavo Chams / Story by Joan Summers

18 February

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October