The Woman Who Climbed the Statue of Liberty

Story by Michael Love Michael / Photography by James EmmermanJul 04, 2019

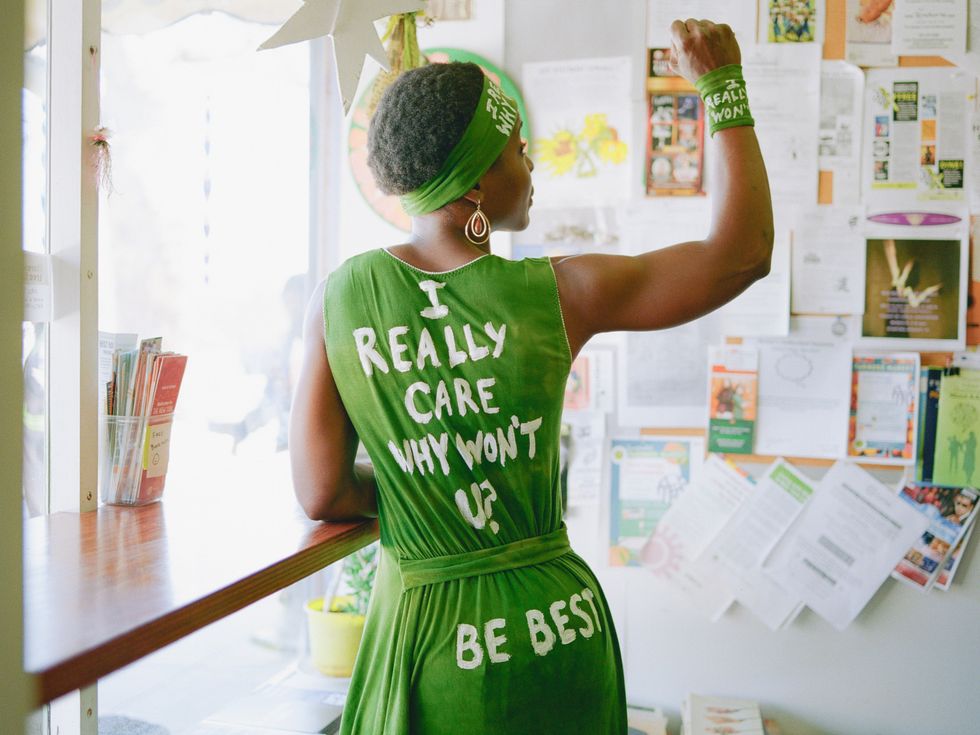

With her daring climb up America's ultimate symbol of freedom in protest of the trump administration's family separation policy, activist Patricia Okoumou is willing to do what others won't: Put her body on the line for her beliefs.

Last year on the Fourth of July, Patricia Okoumou climbed the Statue of Liberty.

Okoumou, who legally immigrated to America from the Republic of Congo in 1994, scaled the iconic structure in protest of President Donald Trump's "zero tolerance" immigration policies, which had resulted in the separation and displacement of thousands of migrant children from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Originally, Okoumou and fellow members of the direct-action activist group Rise and Resist had planned to go to Ellis Island and hang a banner off the statue reading "Abolish ICE." The plan was discovered and the group was asked to leave the island by security, but Okoumou managed to sneak away undetected, and when the coast was clear, she embarked on her treacherous climb up Lady Liberty's base.

Following a three-hour stand-off with rescue officers, during which, according to various New York City news outlets, around 4,500 Ellis Island visitors were evacuated, Okoumou came down and was promptly arrested. A press conference followed the next day, and Okoumou, released on her own recognizance, wore a T-shirt reading "white supremacy is terrorism" and indicted the Trump administration for "throwing children in cages." She attended a pre-trial court date with her lawyers a month later where she pledged to stay out of trouble, while also announcing the launch of #ReturnTheChildren, a mission to catalyze politicians and civilians alike to force the end of the government's family separation policies. It was going to be an improvisatory movement, with Okoumou deciding what types of actions or callouts she would undertake as she went along, until all of the migrant children had been reunited with their families.

These efforts would eventually include Okoumou climbing the Eiffel Tower on two separate occasions this past Thanksgiving during a visit to Paris, despite the fact that she was still facing prison time for the Statue of Liberty climb back in the States. (She says she was inspired to climb the Eiffel Tower because it was the French who gifted America the Statue of Liberty.) She climbed several hundred feet each episode before being aggressively apprehended by French police — a physical struggle that Okoumou says led to pain she still feels in her ribs and back. On February 20 of this year, she scaled the Southwest Key detention center in Austin, Texas, which houses migrant children and claims to take efforts to reunite them with their families, including setting them up with case managers who act on their behalf.

Following the Southwest Key incident, Okoumou was placed under house arrest ahead of her March 19 sentencing for the Lady Liberty climb. On that day, when Okoumou arrived at the Southern District courthouse in New York, she dragged her ankle bracelet with every step. Her mouth was covered in tape, which presiding Judge Gabriel Gorenstein had her remove. Following a heated defense from her lawyers, Okoumou addressed the courtroom.

"This is a case against injustice," she said. "While the world watches in horror, God is taking notes...My fight will continue in the cages [if I'm put there, too]. My goal is to work to get justice for the vulnerable.

"I am not a criminal," she concluded.

The court sentenced Okoumou to five years' probation and 200 hours of community service.

Growing up in the Republic of Congo, Okoumou witnessed horrors many will never encounter firsthand. The country erupted into the first of two ethnopolitical civil wars in 1993 when Okoumou was 19, during the term of its first-ever democratically elected president, Pascal Lissouba, who was eventually overthrown in 1997. When she was in college, she recalls seeing wheelbarrows carrying dead bodies during her walk to class.

Despite all that she's seen, Okoumou says she was "not born with the fear that most people experience," adding that her fearlessness influences her views on interactions with law enforcement. "I'm not afraid of arrest or confrontation," Okoumou says.

This same boldness can be seen in Okoumou's decision to escape the Congolese conflict and immigrate to America, a country where she had no family or connections. She came to the States in 1994 when she was 20 years old and settled in Staten Island. Over the years, she has worked in various social services jobs, including a stint at a battered women's shelter. But currently, she considers herself a full-time activist and has sustained a living through GoFundMe donations from supporters of her work.

Related | Don't Stop Talking About 21 Savage

When Okoumou arrived in the States, the promise of life in a free, democratic society excited her, but her eyes were quickly opened to America's own longstanding challenges, from homegrown political scandals during the Clinton administration to the country's long history with racism. She remembers first learning about the Ku Klux Klan when reading about the Civil Rights Movement. "I would think, Who are these people, and do they really exist?" she recalls.

Later, President George W. Bush assumed office and 9/11's catastrophic events rocked the country. Okoumou saw one of the World Trade Center towers collapse. She later watched with dismay as Bush's War on Terror led to an increase of Islamophobic rhetoric and hate crimes back home, proving, once again, that racism remained a central rot of the country.

By the time Barack Obama was running for president in 2008, Okoumou had become a naturalized citizen and very politically engaged. Inspired by Obama's campaign, she spent time canvassing and encouraging people to vote. "When [Obama] was running, I thought, God, if he wins, that's a sign that you're giving me to stay strong and believe anything is possible," she recalls.

For the eight years Obama was president, Okoumou says she felt relief from the strains of white supremacy, a relief that evaporated during the 2016 election when Donald Trump was elected amidst rising partisanship, racism and white nationalism. It reminded her, like the civil war that divided her home country, that despite the idealistic pursuit of democracy, progress can be battered. Trump's election even led Okoumou to believe that democratic change "can be lost overnight."

Trump particularly drew Okoumou's ire when he gave positions in his administration to Steve Bannon and Stephen Miller. The former, who served as Trump's chief strategist and senior counselor until August of 2017, has supported far-right white nationalist movements around the world, while the latter is Trump's senior policy advisor and was a chief architect of the Muslim travel ban. But, Okoumou says, it was his administration's family separation policy that "was the straw that broke the camel's back."

Ever since then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions promised increased enforcement of the Trump administration's "zero tolerance" policy back in May of 2018, an estimated 2,737 children have been separated from their parents, according to a federal report released this past January. But there are many discrepancies with this figure and, according to this same report, many thousands more children may have been separated from their families as early as 2017 before any tracking system began, further underscoring the chaos, disorganization and mismanagement surrounding the policy. And, although Trump signed an executive order to end family separations last June, long-lasting ramifications like a lifetime of "toxic stress" due to young children held interminably by ICE officials, women having miscarriages caused by stress and inadequate medical care, abuse in the detention centers and illness will outlast this policy. And, as of this February, eight months after the policy was supposed to have ended, administration reports said 245 children were still apart from their families in custody.

In the midst of all this, Okoumou decided the way to make the biggest statement about the colliding issues of anti-immigration policy, family separation, xenophobia and racism was to involve America's ultimate symbol of freedom.

Okoumou says she spent the morning before heading to Ellis Island with Rise and Resist like she does most mornings: in solitude and prayer. She doesn't listen to music or own a TV. She doesn't have a family. She lives alone on Staten Island, but is not lonely. She's an avid runner.

Okoumou did not know that she was going to climb the Statue of Liberty until she arrived there with her group. She'd never been to Ellis Island before and was in awe of the structure's majestic size.

She says she had a conversation with God that morning. "It was like, Tell me again? You want me to do what?" she says. "People have fear, they have embarrassment; there are a number of things that would prevent someone from doing something that would get a lot of attention. I have none of that."

Related | Tierra Whack: Wow, Her Mind

So as her cohorts were being escorted away from the statue's railing, where they attempted to hang their "Abolish ICE" banner, Okoumou scanned the premises, hid from the view of officers circling the base and an overhead NYPD helicopter, and made her move. The climb from the ground to the pedestal the statue sits atop is 154 feet. There were no footholds or grips Okoumou could use to pull herself to the top, and she wasn't wearing a harness or any other support gear. Scaling the pedestal, according to Okoumou, involved hanging on for dear life with the tips of her fingers and toes and using her body weight to pull herself farther up. She took deep breaths before certain pulls. She can't say how long it took because time stood still.

Once she was finally positioned on the statue's base, having completed her pact with God, she took a nap.

Photography: James Emmerman