Lyle Ashton Harris on Self-Love, Fortune Cookies and Punk

By Harry Tafoya

Sep 10, 2024Fortune cookies typically offer throw-away wisdom, flashes of insight so generic or confusing they’re more or less designed to be dumped. But one day after polishing off some Chinese food, Lyle Ashton Harris cracked open a fortune that had unexpected staying power. The artist recreated its text in cherry-red neon, spelling out in elegant cursive: “Our First and Last Love Is Self-Love” (1993). The motto does an excellent job at summing up the philosophy that has informed Harris’ art, which for decades has grappled with the limits and possibilities of representing a self. More than 30 years later, Harris has returned to these words to title a survey of his career at the Queens Museum, Our First and Last Love, open through September 22. (An accompanying book is available now, too.)

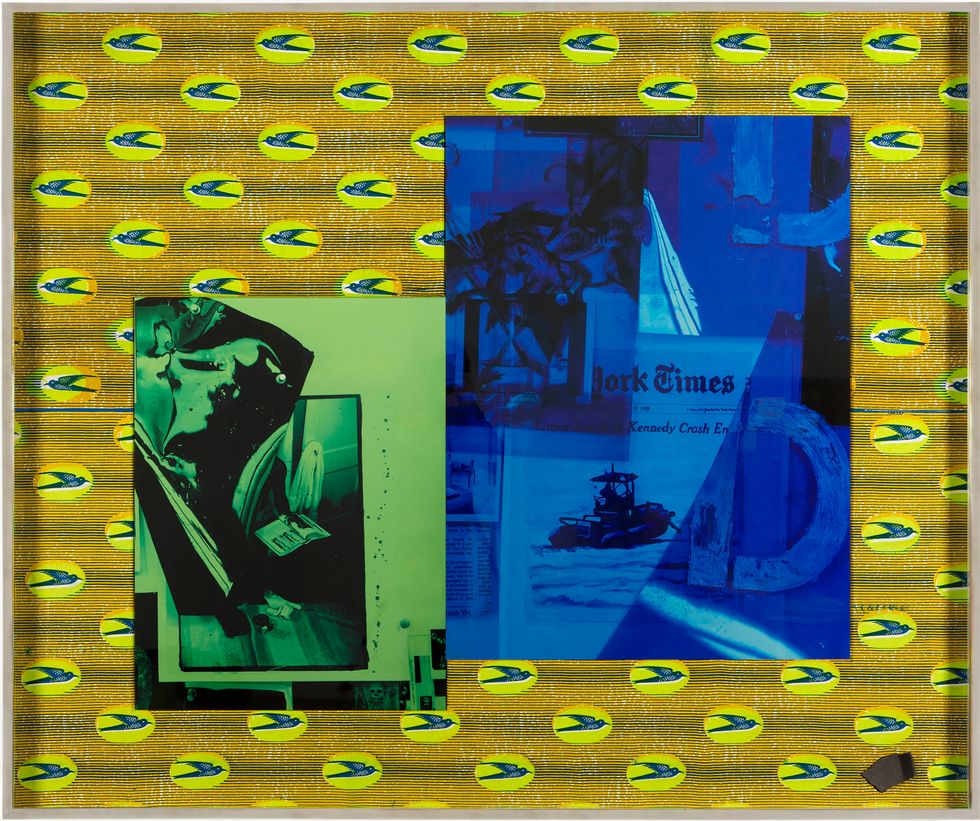

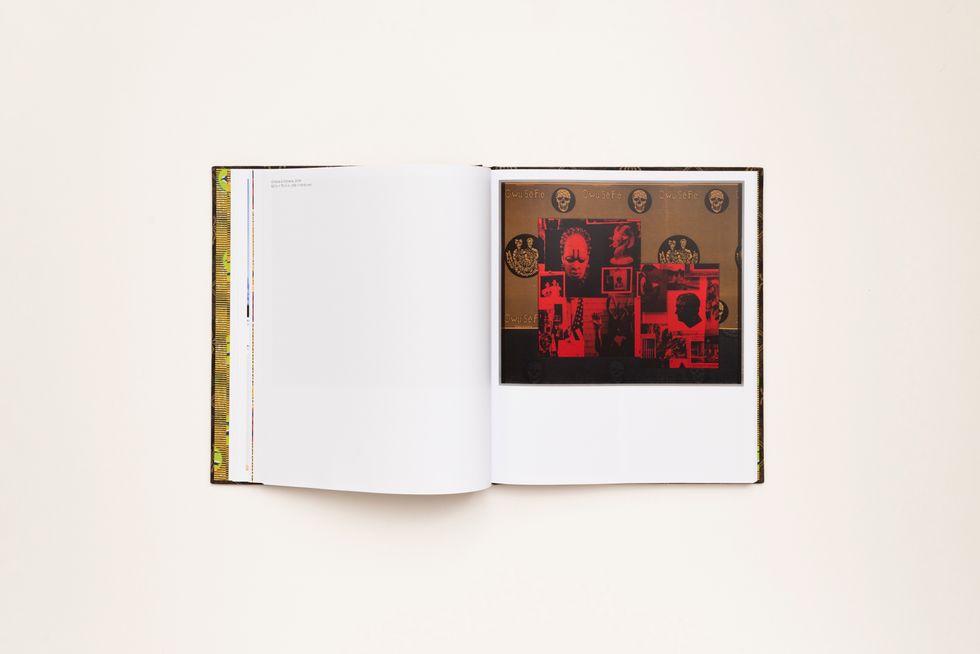

The “self” in Harris’ art isn’t a fixed image so much as a collage made up of many distinct parts. The elements that form Our First and Last Love vary wildly in significance from postcards to gallery fliers to the 30-year-old fortune itself, but they ultimately amount to a lifetime of looking outward and locating aspects of himself in other people. Harris’ assemblage can sometimes resemble a conspiracy theorist’s pinboard, drawing through lines that link discreet references and events into a messy tapestry of emotion. A series like The Watering Hole (1996), made in response to the media storm around Jeffrey Dahmer, probes sex, shame and violence; sidling up to the modern boogeyman and locating where he stands in relation to the killer’s perversion and race obsession. Sometimes the way into a piece is through characters, like in Billie, Boxers, Better Days (2003) where Harris uses drag to channel Billie Holiday’s defiant, tasteful femininity to bare-faced masculine antagonism, all the while asking: which is the more palatable kind of Black anger?Harris became famous with the dawn of “post-Blackness” in the ‘90s art world, which cast off the burden of “having to represent the whole race” while maintaining a sharply critical, politically committed, panoramic understanding of what it meant to be Black. Like neo-soul, its analog in music, Harris’ art sampled casually and freely, weaving threads of radical thought, steamy sexuality and diasporic tradition. His work existed at a time where he could afford to treat heavy subject matter with a light touch, referencing texts without being hidebound by them. The full face of makeup in “Saint Michael Stewart” (1994) is as playful as its subject matter — a man killed by the police — is deathly serious, a way of taunting the meat and potatoes masculinity of the NYPD while declaring a sly form of queer allegiance. My personal favorite is the rude, hilarious Polaroid “Fanon Postcard, Whitney Independent Study Program” from 1992, which bastes a postcard referencing the widely-cited, anti-colonial thinker with a polite spray of cum.

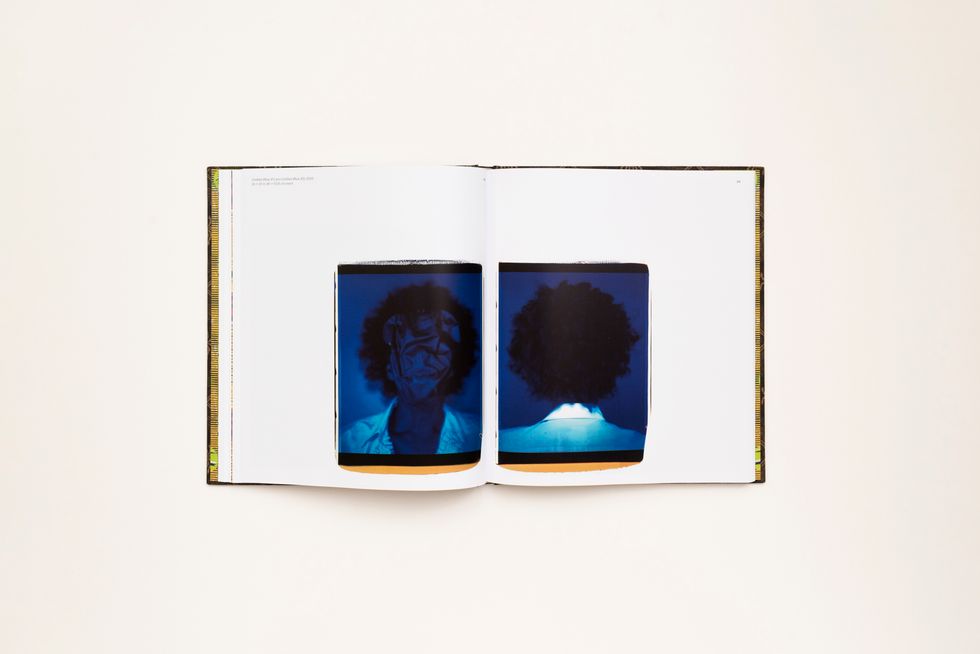

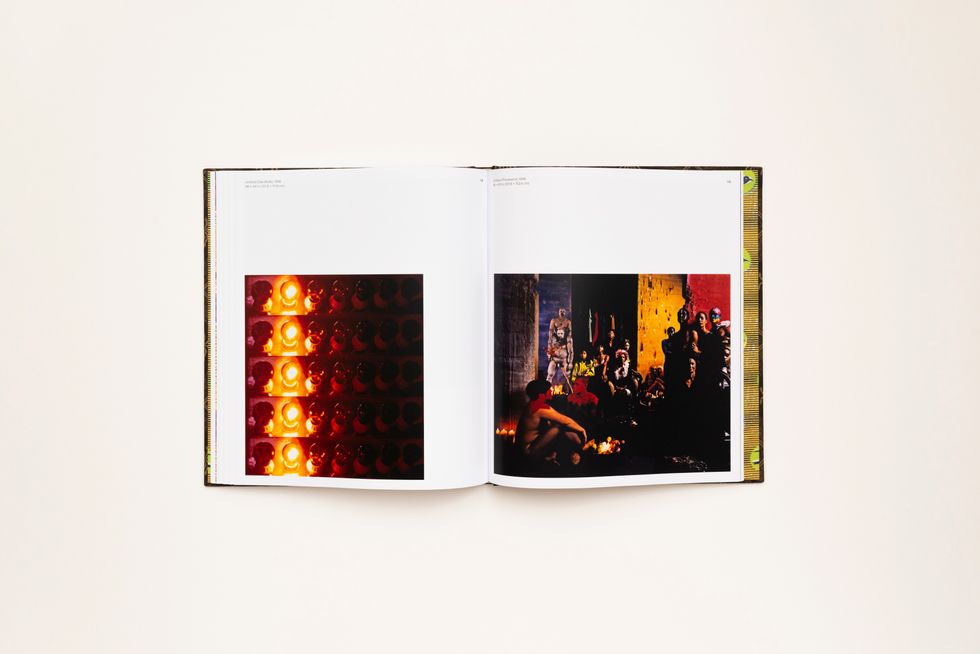

Harris is probably best known for his photography, which has ranged in style from ghostly monochrome to punchy, saturated colors; from ultra-stylized photo shoots to silly, spontaneous point-and-shoot. Like his contemporaries Nan Goldin or Wolfgang Tillmans, Harris captured the casual glamor of a fully engaged life: always somewhere to go, always somewhere to be. Friends, legends, heroes and lovers appear on a first-name basis at parties, marches, openings, and conferences. The poignancy of Harris’ best-known series, the Ektachrome Archives, isn’t simply that his models are young but that together the artist and his subjects form a varied but unified front, animated by purpose and at fierce odds with the negating forces of AIDS, racism and death.

For years, Harris has remixed this imagery, returning again and again to these photos and superimposing his changed understanding upon them. In his recent Shadow Work series, the past and present converge against printed fabric from Ghana, where he’d spent several years teaching. Ghanaian fabric is loaded with cultural associations specific to mourning, which casts a slight but meaningful shadow on the retrospective. Any understanding of our self is bound to become obsolete in time as we grow older and survive loss. With Our First and Last Love, the audience has access to almost every version of Harris as he’s continually found new ways to look in and reach out.

PAPER sat down with Harris to discuss punk, his childhood in Tanzania, self-love and funerary fabrics.

A bit of trivia that blew my mind is that you used to date Tommy Gear from [legendary punk band] The Screamers. Do you have a background with punk at all?

That’s a good question. How do we define “punk”?

I’d be curious about your definition.

Well, counterculture, yes. We met in his post-Screamers days. But I would say, definitely growing up in the late ‘70s, early ‘80s, going into clubs in the city, being exposed to second-generation punk culture in terms of fashion and music, traveling to London a little bit. I wasn't obviously on the early emergence of the punk scene, but in terms of its effect on the broader culture, relationship to music, fashion.

Where does your defiance come from? It doesn’t seem your work seeks to please; it’s very matter-of-fact.

For my particular trajectory, it’s important to say — having grown up as a child of the ‘70s and my mother, taking my brother and I to live in East Africa. She was working directly for the Ministry of Education, so we had the option of going to an English-speaking Swahili school as opposed to being ensconced in the NGO community or the expat community. At an early age, we were exposed to other modalities in terms of thinking about moving beyond the confines of American culture. My mother's second husband was in exile from South Africa, he left after the burning of the passes in '59. He was very much into music. So it wasn't punk as we know it in terms of what you said, but it was a radical black African understanding of music as resistance.

You think about any given Saturday when my stepfather wasn't working and was blasting music. There were a lot of young kids in exile who experienced the atrocities of apartheid who would come to the house. So we were ensconced in the bosom of American family life at the same time that we were exposed to resistance movements, not only in the US. When I first came back from living in Tanzania, and going back to the school I went to in the Bronx, it was just a very different way of thinking about one’s sense in one's body and to one's relationship to culture.

So when you were there, [the Pan-African socialist Julius] Nyerere would’ve been president.

Precisely. In fact, you know, I have a small garden up here that first came into existence the summer of George Floyd, and I planted two beds, and now they're eight. But I was thinking that the last time I had quote, unquote, "my hands in the dirt," that would have been a few decades ago when I lived in Tanzania, where Nyrere required that everyone have a plot of land. You know, the idea of being self-sustaining and et cetera.

Did you have a smooth transfer back to the States? Was it a capitalist overload shock to go from Africa to New York in the ‘80s?

That was challenging. I was 11 years old, I had missed the prompt that puberty had sprung. And it was much more of an idyllic environment. I remember coming back and just being shocked by the level of advertising and also in terms of the pornographic gaze in advertising. That was really fascinating to see, eventually I got used to it but it was like, wow, this hyper-exposure to money, fetishism.

The fortune cookie that gave your show its title, “Our first and last love” — why did that text resonate with you? Did it stick with you for years or did you find it years later?

I was with Tommy Gear in Seattle and we were visiting for his mother's memorial. We were in Pike market and we were having Chinese food when I came across this fortune. I was still at CalArts at the time, I believe it was my last year of grad school. I think it probably had a lot to do with the environment at CalArts and to the type of work that I was doing there in response to it. In a way it probably became a prompt to myself, but also a prompt that was generative in terms of other works. For example the neon itself as well as threads that appear and reappear over the last couple few decades. And it is interesting because what does it mean that a fortune I got in '92 would be the title of this show?

Why return to the prompt now?

It's interesting that the neon first showed, I believe in ‘93, it's one of the earliest works in the show, and this is the first time that it has shown outside of its first iteration. And I thought it'd be nice to include certain works that had not been shown before or had rarely been shown, and I think the curators Caitlin [Julia Rubin] and Lauren [Haynes] did a really great job to try and to piece together various elements and to see the synergy between them.

So as far as them including that particular piece, that constitutes the title for the show: titles are important to me, and we wanted something that did not just say "surveys" but something that felt much more poetic and more invitational, but also something that became a vessel where one could explore or enter into a sort of a certain line of question. And it is curious that, given that the text was from 1991, and the fact that it was something so everyday for me, it obviously resonated. I think it's important to understand at the time that AIDS activism was happening. The program had a focus on neo-Marxism, there was an emphasis on discursiveness in terms of writing and language and text. So in a way, it was almost ready-made to address some of those things; there was something playful about it but also common.

What I like about the show is that it’s reaching outwards, it seems like you’re locating aspects of yourself in all different kinds of places. How would you distinguish between self-love and narcissism?

I can’t, and it’s not my job to do that. But I will say that the show would not be resonating the way it is without having systemic shifts globally and locally in terms of the idea of self-care. People are yearning for that sense of care and intimacy. It provides a salve in terms of thinking about slowing down other modalities, and that’s maybe why [the exhibition] is resonating with people across generations.

I wanted to ask about the funerary fabrics that you got from Ghana. Consistently through your career, you remix work that you’ve previously made. But was bringing in the funerary fabric your way of bringing death into the work, or was it marking an end of some kind?

My first exposure to funerary fabrics was through prints. My first semester in Ghana, I traveled with my partner to where his uncle was, and a year later, this uncle had passed away. So I was struck by the funerary rituals in Akan culture; not only the music and the dance, the formality of it, but also cloth being a major component in terms of how that symbolizes various stages.

I started acquiring fabrics in 2007. And then after returning to Ghana to visit — and the confluence of that time with the ending of a relationship — Ghana had left such an impression on me. I think it was about grieving. It was a way of processing and formally investing some energy into the work. And about radicalizing some of the traditions associated with the materials as well. Maybe it is the death of the Age of Innocence around that. Grieving not just in terms of my own experience but in terms of grieving over a certain type of romantic notion of the fabric as something one can hide behind.

One thing you’ve done in your work is to approach certain celebrities as a kind of conduit for engaging in complex ideas, like Billie Holiday and Michael Jackson. If you were to update that project today, who would you take on?

To be discovered. I’m in the gestation period right now. Stay tuned.

I’m also very interested in the way you approach violence in your work. What draws you towards it as a subject and what is your strategy for handling it?

Maybe experience it personally. It’s something I feel gets under your skin. And if I don’t address it, it will address me. It’s a form of working through something.

Photos courtesy of Queens Museum

Headshot by Lloyd Foster

Related Articles Around the Web

MORE ON PAPER

ICONOS: Pepe Aguilar, El Oficio del Tiempo, la Voz del Silencio y el Peso del Legado

Español

Jan 19, 2026

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October

Entertainment

Matthew McConaughey Found His Rhythm

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

30 September