Julien Ceccaldi Writes a Manga Human Comedy at MoMA PS1

BY

Harry Tafoya | Apr 29, 2025

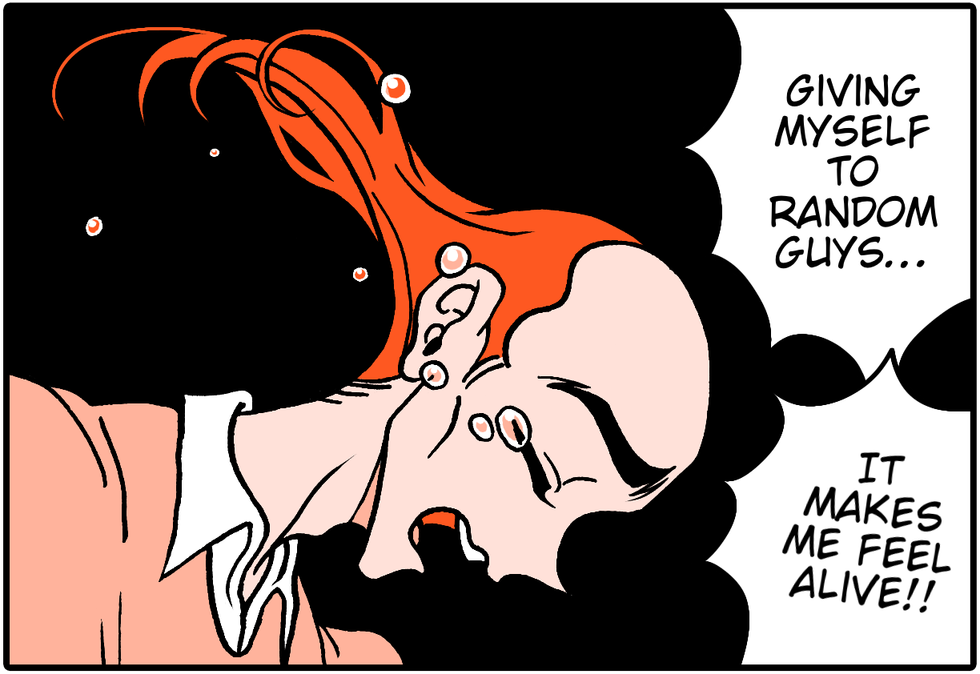

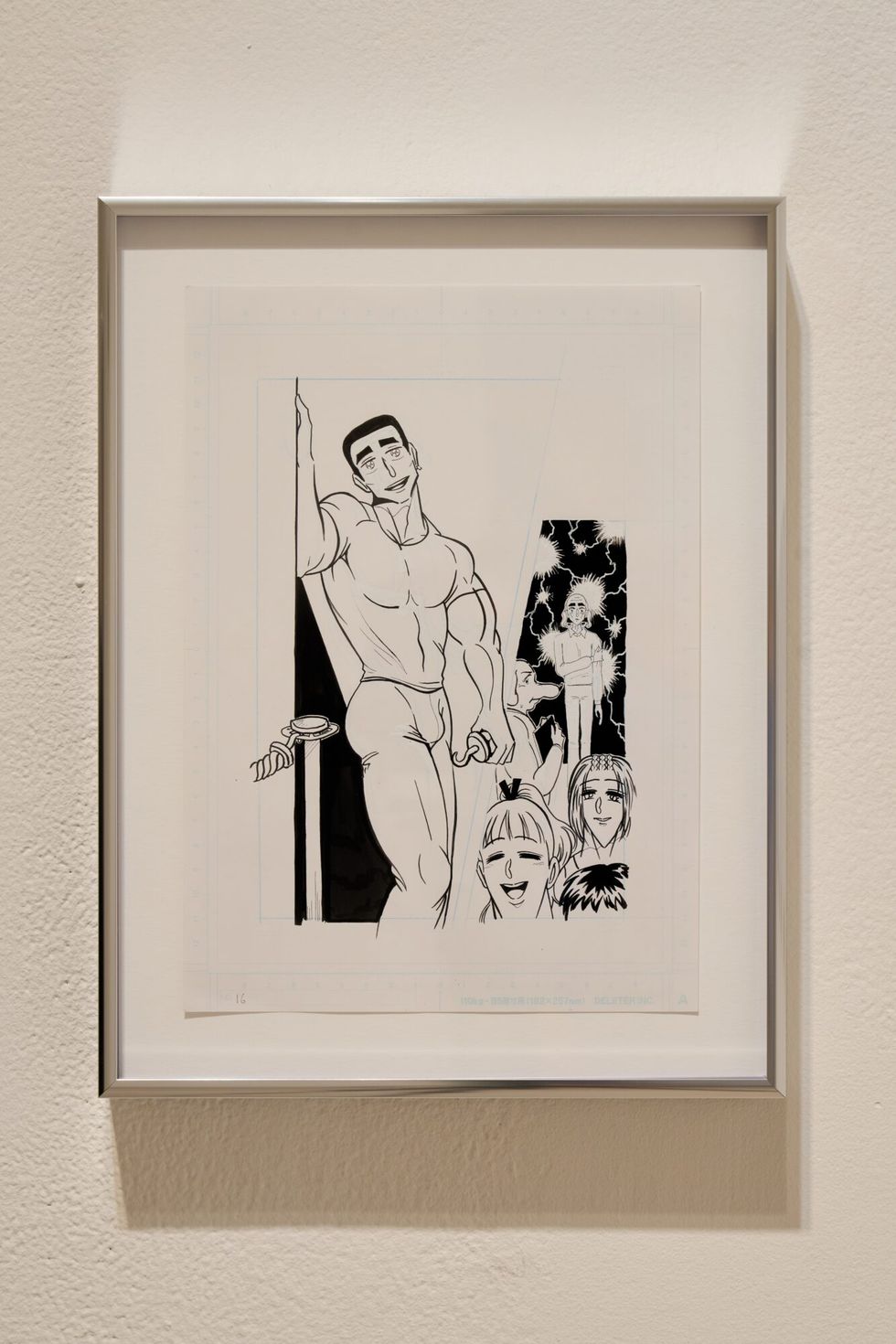

There’s a moment in Julien Ceccaldi’s animated short film Human Furniture where the main character, Francis, suddenly comes undone. Out at a club for the first time after a long stay with his parents, he bumps into his long-time crush: a charming-but-clueless himbo named Simon. Ceccaldi depicts Simon as a mountain of muscle in a skin-tight shirt, topped by an angular face so blindingly handsome everyone around him practically melts. Francis is puny by comparison, with sparkling eyes, a twink-y build and a hairline in firm and humiliating retreat. You’d be tempted to call him the more plausible character of the two, but both are so extreme in the way they’re drawn that “realism” hardly seems to factor in at all. When Francis tries to duck out of the party, Simon pulls him into a drunken bear hug. The sudden proximity between the body he longs for, and the reminder of the emotional gulf separating them, causes something to break inside of Francis. “This is not the first time my tear drops have rolled down his meaty pectorals,” he thinks to himself as he’s left silently weeping on the dancefloor. In an instant, the world disappears and Francis is swept away by a cascade of his own tears. “Here I go,” he thinks, “drowning in memories again.”

Manga is an overblown style of art, which is one of its greatest strengths. It’s a genre that honors the extreme emotions and active imaginations of its fans by matching form to feeling. The epic inner lives of its protagonists can rage on for pages, zipping past in a frenzy of cartoon action or unfolding gradually like a slow-motion daydream. Conflicted personalities are given voice by a whole cast of characters, who can embody all the parts of a fragmented self: he’s the serious one, she’s the stylish one, and they’ll never stop until they finally get revenge. In its most remarkable moments, the narrative dips into pockets of wordless poetry, with illustration carrying the mood into difficult places where language can’t follow.

For years, Julien Ceccaldi has sought to break out of the defined limits of a comic panel. The French-Canadian artist uses his talents as a painter, designer, filmmaker and sculptor to project his characters’ psychology into immersive, full-blown exhibitions. His work has been featured in galleries and sent down runways, fitting neatly among contemporary fusers of fine art and anime like Julien Nguyen and Kye Christensen-Knowles, while firmly occupying his own lane. His first solo museum show in America, Julien Ceccaldi: Adult Theater at MoMA PS1 is both a career high point and another entry in a long-running story that the artist has told about the dramas and adventures of Simon, Francis, Solito, Marie-Claude, Haydee and a whole host of other long-running avatars.

Despite the initial steaminess of its title, Adult Theater is more of a buddy comedy than a sexy romp. You don’t need to be immersed in the deep lore of Ceccaldi’s work to follow along. Like switching on Sailor Moon or The Rose of Versailles at random, his subjects announce who they are at nearly every turn. Caroline is the cool diva, Oscar is the fairytale prince and Francis is the lovable, lovestruck loser. The mischief they get up to and the positions they occupy shift from episode to episode, piece to piece. Even if their personas are relatively stable, Ceccaldi is artful about leaving a raw edge to their psyche. A major inspiration to the artist is the filmmaker, Catherine Breillat, whose dark fairytales and brutal character studies mix a love of surface with heart-rending abjection. With Adult Theater Ceccaldi reveals himself to be her star student.

Throughout the show, the artist treats the space like an exploded version of his sketchbook, building out flat illustrations with 3D elements that warps the line between the characters’ world and ours. The first piece the viewer is likely to encounter is “Curious Girlfriends” (2025), which features two life-size Ceccaldi divas painted onto a clear panel and peering around the corner into another gallery. It’s a mirror of the audience’s own interest and a clever cue to direct our attention: ohhhh, the rabbit hole starts over here.

These little touches carry over throughout Adult Theater and showcase again and again how clever Ceccaldi is at conceiving new dimensions for his work. In his stand-out mural, A Collection of Little Memories (2025), Ceccaldi depicts a queue of anonymous lovers lining up to get swallowed whole by Francis’ gigantic head. It’s a study of ravenous appetite, using the grotesque scale and gnarly detail you’d associate with an anime like Akira, to show how insatiable his longing is. The bridge that both connects the audience and carries his hook-ups over to their doom is an IRL step ladder jutting out from the wall. Isekai world-building overlapping with your local hardware store.

Alongside older pieces (like the excellent Pompeii Bathhouse (2017), the most exciting work in the entire show is the adaptation of Ceccaldi’s drawings into short films. They’re very minimal, really just sketches bound together by music, some rudimentary animation and the artist’s lilting, slightly-accented voiceover, but they speak to a whole universe of potential. You’d hope that someone would see this show and hand over the budget to give Ceccaldi a full series. After seeing Adult Theater, you can’t wait to tune in again.

PAPER spoke with Julien Ceccaldi about bottle service, make-up tutorials, gay saunas, Gothic art and much more.

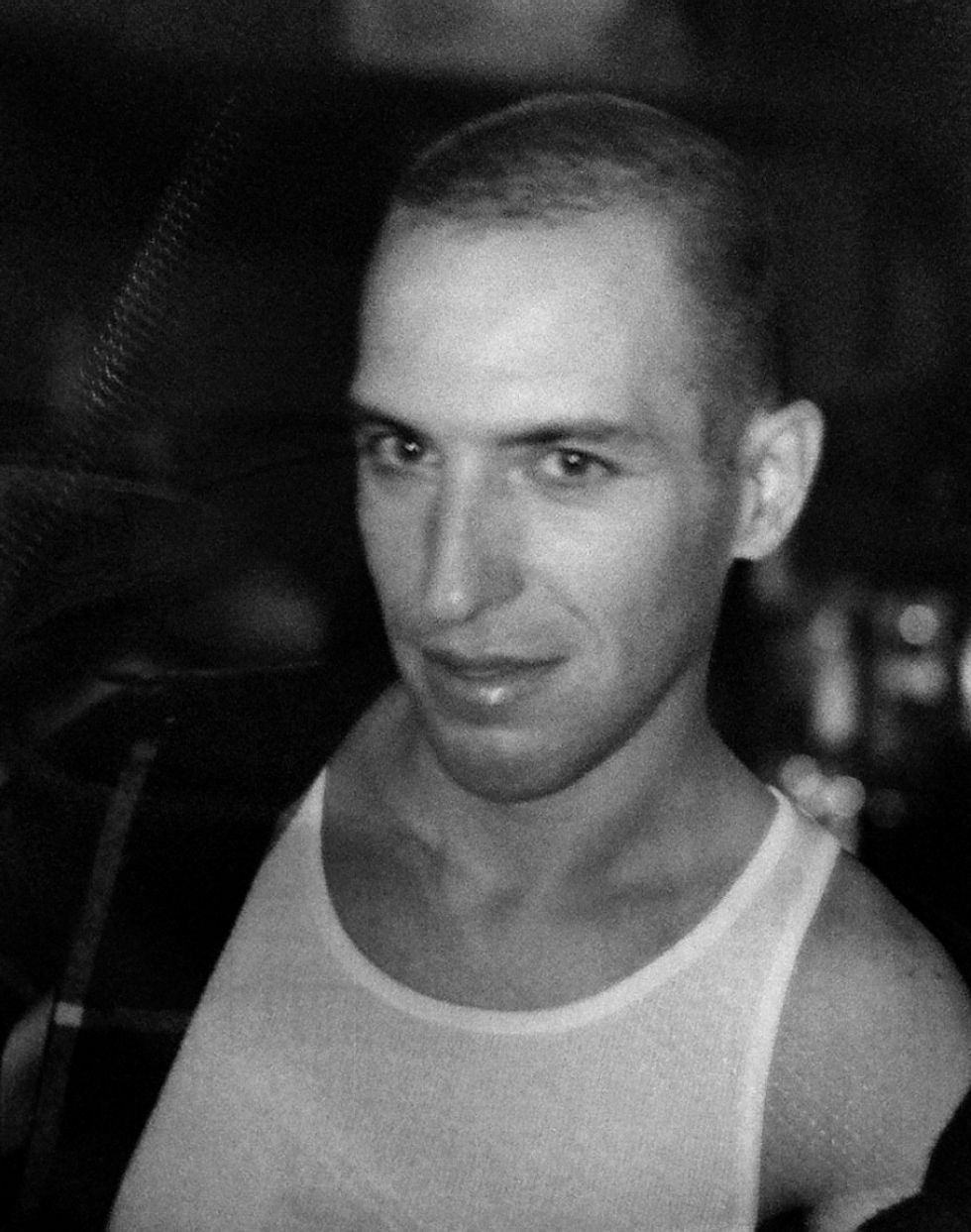

Portrait of Julien Ceccaldi. 2024. Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery Photography / Film. Photo: Hanayo

Were you kind of a girly boy growing up?

Yeah I was asked to swish less when I walked, I was bad at sports, I drew princesses.

I ask because your work feels like it's quintessential girly-boy art, there's both intense introversion and a real commitment to fantasy going on. Could you talk a bit more about the things you were drawn to as a young person?

I think they all fall somewhere on the girly spectrum. It goes kind of from Rainbow Brite to Sailor Moon to YouTube makeup tutorials to Catherine Breillat movies.

Were you doing makeup?

I beat my face a little, but my technique sucked. I did wear concealer in secret most days in high school, just because I had bad pimples. Sometimes my girlfriends would notice because it was not a good color match. I'm still mortified.

When did you first get into anime?

I guess, like, from childhood. I don't know when I got a video from the internet. It was my favorite cartoons to watch growing up, and then as a teenager, there was an era where video game magazines would talk a little bit about manga and anime and in them, they would share websites to visit if you wanted the latest news. There was this website called Anime Web Turnpike, which was a directory that had thousands and thousands of websites pertaining to anime fandom. You had official news websites, you had fan artists websites. And so I think I was actively pursuing that world as a teenager in the 90s and 2000s.

Did you ever participate in events? Or cosplay?

No, I wasn't close enough to Paris when I lived in France and in Montreal, at the time, it was kind of too small for there to be fan events. So I would read about French conventions and I dreamt of going, but I never went.

One thing that strikes me as being very true to anime is that you have these characters that exist at different levels of coolness and uncoolness. You'll have the most composed character one moment and then something will trigger them and they're suddenly freaking out inside. I was curious about how you related to that and how it's been an influence on your art.

I think you feel good imagining that all the cool, collected people were freaking out inside. There was this one-off reality show, Tool Academy, where these strong muscle-y jocks, who were kind of bullies, do exercises with a therapist. One of them has to draw a self-portrait, and all the big, macho, muscle-y bullies drew themselves as frail, stick figures. That was a cool twist that they were putting all this energy into appearing strong, but inside they felt scared and emotional. I think the kind of contrast was inspired by how I could feel sometimes going to the club. I don't know how it happened, but my friends would drag me to the capital "C" Club with bottle service. So I'd say the origin of these power imbalances come from those experiences where I'm 17 or 18, tiny in a big man's blazer, surrounded by adults dancing and drinking. And looking back, it must have been quite a spectacle, I really looked out of place. But eventually I learned to love the club — the less bottle service-y club.

Another thing about the club though is that part of dancing and going out is also about feeling comfortable in your own skin. How has anime influenced the way you depict sexuality?

I'm not sure I reference anime when I depict sex. The manga and anime I consume don't have that much sex, or if it's pornographic work, I don't really reference Tagame [Gengoroh] or the yaoi stuff. And for me, anime is really in my head. It doesn't lead to me feeling embodied at all. It's just me alone in my room, and I rarely even talk to friends about it, not embodied at all. I came more into my body through going to the club.

Was there any shame around anime for you?

It was put on me by other people growing up. But I don't think I obviously don't give a shit anymore, because the influence is everywhere in my house, in my work. But growing up and even in university, the only rule I had in art school was that the teacher didn't want us to draw something inspired by anime.

And look at you now! But also like... why?

I don't think it's because the teacher hated it. They just wanted us to use the school time to open up our horizons. I guess I'm not upset about it.

When I asked about sex before, it seems like you do have these really eroticized, super muscular bodies —

I think of them as more athletic than erotic.

It doesn't seem like it's work that is about their physique. It's all about what they represent for the head as fantasy figures. It feels like a lot of your work is about the internal headspace.

Yeah that's really the main strength of the genre of shōjō manga, it really elaborates on characters' interiorities. That's what differentiates mostly from shonen, which is more for boys, which is more action or adventure driven. It's about tasks and action a bit more, even though you do get a window of the characters feelings. But shōjō is really delving into psychology, and I think my favorite books and films do that too.

Part of what's great about shōjō as well is you have these figures who are so perfected, they are perfect ideals.

They're photogenic, maybe in a more conventional way, like the hot people in shōjō are probably more thin and pretty. I thought it was interesting to like to use the tropes of that world, but apply them to characters that align a bit more with like the Tom of Finland standard of beauty or the more handsome kind of androgyny.

It’s almost like smashing Barbie and Ken together. Could you tell me about fashion because it feels like a very big part of what you do. You've done collaborations with designers [like Ottolinger, Kenzo, & Arielle de Pinto] previously — how has that inspired you?

I was keeping up with it more in the 2010s, and then in the last few years, I've focused more on the character stories, and I've neglected their outfits because I just wanted them to have a recognizable uniform. But early on, I really used the characters as models to draw my favorite Versace or my favorite 2000s club-wear that I saw in music videos. I always think of clothing like armor and as costumes for play. So I think of it both to display a character's inner world, but also to display what the character wants to show to the world, even if they might not be how they live. It's fun to think about clothes. This show is very fashion-oriented, but I consider it especially when I need to draw a character when their story is a bit about being on trend. So that's when I'll pull the K-pop references, or I'll have fun with the accessories and the styles.

Your work is not just two-dimensional. Your characters themselves are literally flat, but they interface with the wider world through these built-out installations. How do you come about bringing these characters into a 3D world?

My favorite thing about comics is that when you're reading, you're saying the words in your head. And so I love if a character is going through despair, imagining someone saying to themselves a really self deprecating line. And then I like to think, "Oh, well, let me make them think about treating others better, or treating themselves better, maybe." And so the characters become really themselves through dialogue. In the space, when they're painted in life size, they're meant to be kind of like photo props and fellow audience members. And then when you go to a club and you see someone on Instagram, but you've never talked, so you feel like you know them a little, but you're also aware that you can strike up a conversation because you've never met in person. That's kind of the effect I'm going for.

We talked before about space in terms of these zones where the rules of gravity don’t necessarily apply, could you tell me what draws you to them?

I got the idea for that from this book on Gothic [art], and they had one chapter on the maze and I enjoyed thinking about how gay saunas often reflect a labyrinth concept or architecture. And I also don't really care for backgrounds. They don't need to make sense. I use them more for practical reasons or symbolic reasons. So as long as there's a door and a window frame, it doesn't really matter that it's where it should be in a three-dimensional space that makes sense.

I want to ask about the space that you conjure in the show. You have a lot of fake outs. Like the girls peeking around the corner, we can see them but we can't follow. How did you want the gallery to work for you?

I was thinking about how some gay saunas have sections that reflect non-erotic spaces, like some gay saunas will have bath houses that look like a standard bath house. And so I was hoping walking through the exhibition feels like, well, both walking in an adult bath house and a normal bath house, and then being similarly watching a play and being onstage in the play.

One of the things that I really like about the show is that you have these characters that seem to be constantly in conversation with each other. What is the kind of conversation that you want to have playing out among them? And how do you fit in among them?

I mentioned theater, but maybe it’s more a sitcom, and the comedy comes from the clash of these different characters’ points of views and experiences, and so there’s a degree of self-portrait, but it’s also just a portrait in general of different types of people. The idea is that the reader could identify with one person or the next or consider their friend’s point of view through putting themselves in someone else’s shoes via the comic.

I’m like Solange, the main character in [Catherine Breillat’s film] Tapage Nocturne, she talks about herself and her lovers non-stop throughout the whole movie — she talks to herself, to others and even directly to the audience. She says that’s how she discovers what she thinks. I’m just like that.

Portrait of Julien Ceccaldi. 2023. Photo: Angele Balducci

Photos courtesy of MoMA PS1