Ivy Wolk Worldwide

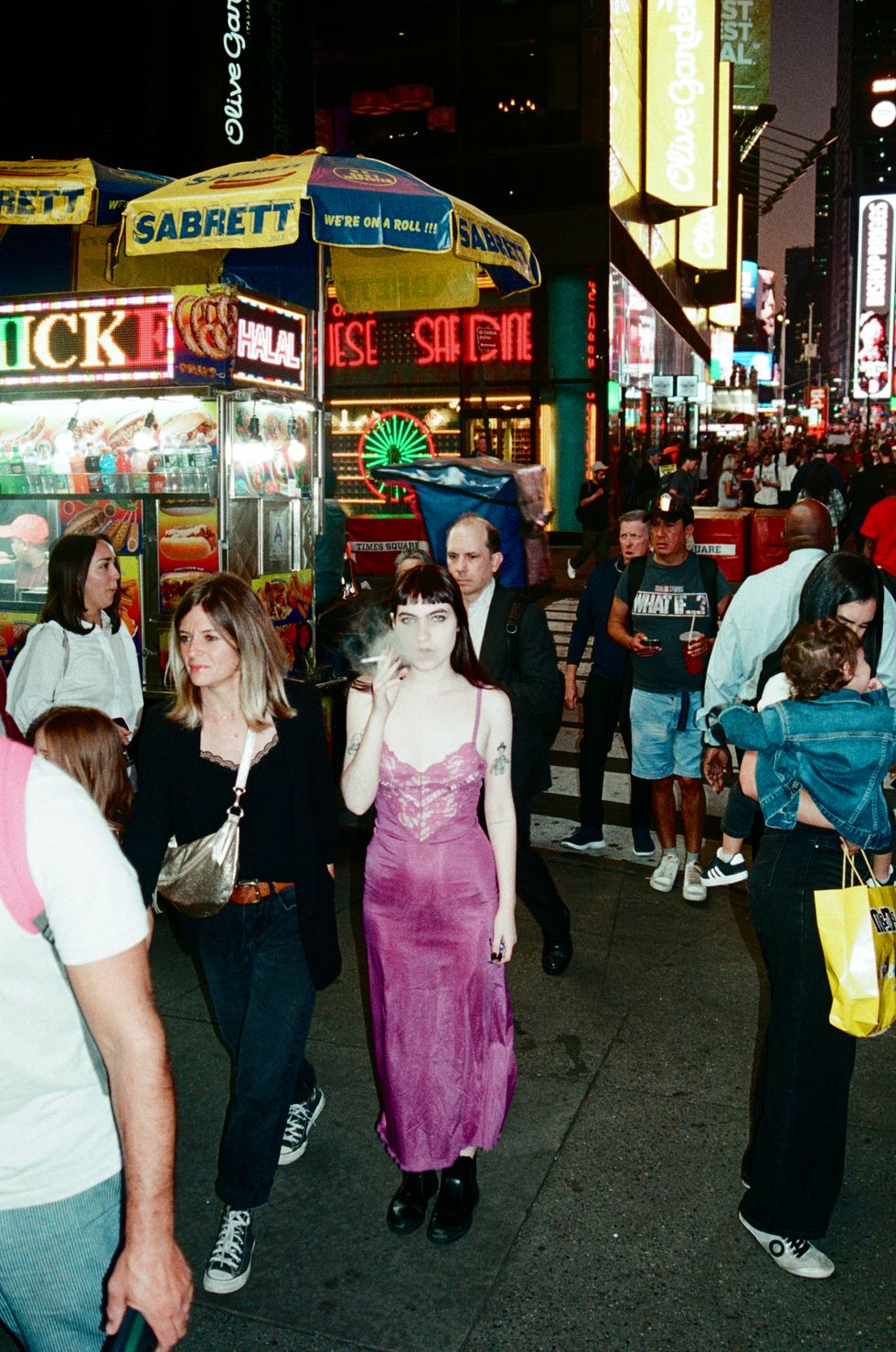

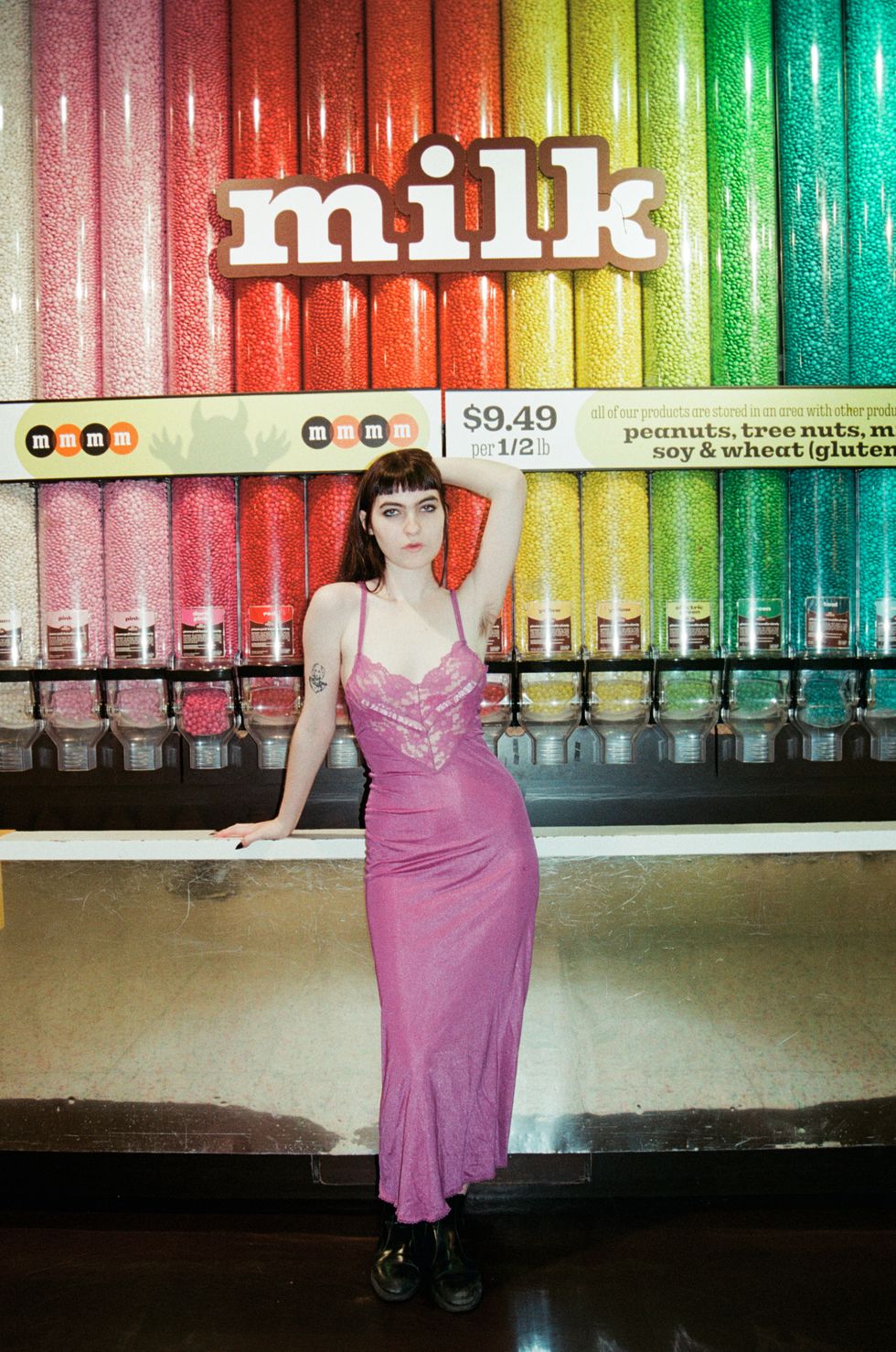

Story by Tobias Hess / Photography by Taryn Segal

Dec 17, 2024

“I was having a panic attack in the street, holding my heels, heartbroken,” Ivy Wolk recalls while sitting with me in Bryant Park on an unseasonably warm autumn day.

The actress and perennial internet main character is talking about her time at the Cannes Film Festival, where she was attending the premier of Anora, Sean Baker’s landmark film which won the Palme d’Or. Wolk, who plays the part of Crystal in the film, was five minutes late and a French male security guard prohibited her entry. A group of young women noticed the misunderstanding and helped her translate her predicament. She thought these women were her “allies,” but then they began to film her.

“Tears were running down my face,” Wolk remembers. “[I said to them,] ‘Please don't film me right now. I’m sobbing, crying, dry heaving. This is my movie.’” An employee of the theater eventually recognized her and let her in, but the incident would live on. A woman from the group posted the footage as part of her banal travel vlog and millions would soon see it via TikTok and X — the social media platform where Wolk exists in frequent virality and infamy. One post on the site describes the incident as “cement[ing] [Wolk’s] star status” as a “diva in the making.” But while her many, mainly queer internet admirers were turning her “meltdown” into fodder, Wolk was on a plane home to New York City, bracing for turbulence, drinking wine she had snuck onboard and using in-flight WiFi to track the video’s virality.

“People have been using my image for really nefarious, disgusting purposes for years now,” Wolk sighs. She recalls one time, when she was 14 at Disneyland with her mom (this was around the time she began to go viral on TikTok), when two girls went up to her to ask for photos. At first she turned them down, but her mother beckoned her to be kind to strangers. She took the photos and saw, days later, that the girls had posted it online as a joke. Wolk was to them a walking meme.

Wolk has been hyper-online and hyper-public since she was 13 years old, when she was an uber-outgoing adolescent in Los Angeles’ mid-city who just happened to have the gruff sense of humor of a veteran club comic with a hint of shock jock panache. On TikTok, hundreds of thousands of followers tracked her every take — on culture, on her health, on coming of age — which she posted to her TikTok account. Her words were sharp, and her confrontational approach to her digital naysayers, addicting to behold, but the online spectacle surrounding her often devolved into a food fight, messy and absurd.

Her rise came during the bubbling years of a fractious online cancel culture. Wolk’s rising status and bombast made her a prime target, but in the contextless digital ether, few were stopping to consider what could have been the foremost fact: Ivy Wolk was barely of high school age. “My form of rebellion was my rhetoric and my comedy,” she offers. Whereas other teens she knew were rebelling through their sexuality or with illicit substances, Wolk and her crew of friends were operating from an M.O. of “say and do whatever you want.”

For many young people, the consequences of verbal recklessness would be social reprisal or in-school discipline. But Wolk’s lilting, sharp tongue and her penchant for internet chaos has made virality follow her like a sacred, destined power. It’s a power that she’s both wielded and succumbed to over the course of many cycles of both internet cancellation and comeuppance. And as she recalls these many incidents over the course of our two interviews — one in midtown before this photoshoot, and another on Zoom — her story feels almost mundane and typical; teens say provocative shit every day; young artists blow up their little lives all the time. But, as our conversation reveals, the mega-spotlight of the internet has made her simple story appear more extreme and ghastly. When Wolk fucked up, her life caught on hot, red fire. When Wolk had a spiral, her world sank into the sea.

At 13, Wolk was cast on the Freeform sitcom Everything’s Gonna Be Okay. She was already well-known online, but the execs at Freeform — the then-newly rebranded ABC Family (a Disney subsidiary) — forced her to delete her social media. She eventually went back on TikTok against their will and accrued half-a-million followers in 11 months. This period of prodigious posting is what cemented her in the pop culture zeitgeist (“She was TikTok,” as one friend put it), but there was a cost to the fanfare. As her status rose, Freeform was assembling a dossier against her, Wolk says, taking note of every post, every comment, every transgression.

“I was getting phone calls from my manager like, ‘The team at Freeform is upset again,” she remembers. “I wouldn't quell my voice. Even under siege, even at the risk of losing a job... I don't bend to anybody's will. Still don't and never will, especially when I was fucking 15 years old.” She offers the explanation as if it's self-explanatory, but when I suggest the opposite — that a 15-year-old would be expected to bend to the will of authority eventually — she rebukes it. “I believe in freedom. A woman's voice should never be censored.” In the end, she was not asked back for the show’s second season.

“Ivy’s genius comes from her honesty,” shares writer Mackenzie Thomas, a close friend of Wolk’s. “If anything, Ivy is putting out things she would want to consume. She’s willing to sacrifice a lot of her privacy for entertainment.” Indeed, Wolk’s internet life feels like a public diary, but her stream-of-consciousness style is often received as insensitive and shocking, rather than personally true — she’s been called “problematic,” “right-wing,” and most extreme: “a predator.” “90% of the stuff people believe about Ivy isn’t true. It actually baffles me,” Thomas relents.

Wolk cites Courtney Love, Sandra Bernhard and Amy Winehouse as heroes: “No matter how meteoric their fame got, [those were women who] stuck to their guns and were like, ‘No, this is my art,’” she says. “I care about a bitch who crashed out and lived to tell the tale.” It occurs to me, though, that one of those women, Winehouse, hasn’t lived to tell the tale, and another, Love, has done so at a tremendous personal expense. Plus, “crashing out” can look like a lot of things, and there have been moments when a “crash out” verged on something permanent.

“The reason I don't have TikTok anymore is because when I was 16, I posted a public suicide note, and it became a meme,” Wolk shares, grimly. “Girls were posting themselves dancing in front of it. Everybody in the comments was like, ‘Ding dong, the witch is dead.’” The moment shocked her and renewed her will to continue on, but the darkness of the mob still scarred her. “It has been deeply traumatizing,” she relents.

After, she was offline for a few years, finishing school and working on her stand-up act in Los Angeles. She eventually ended up going to Emerson College in Boston, where her social media persona preceded her. She had attended online school for the three years prior, so this was the first time she faced real social reprimand from IRL peers for her online antics. The sketch group she joined held labored debates about whether to “platform” her. She was, as she tells me, a “pariah.” But while she faced backlash at school, her acting career was beginning to rev up, and she quietly came back online to X (FKA Twitter) where she still had many fans and haters.

It was around this time that she was cast in Anora. She got the part after she attended a screening of Sean Baker’s Red Rocket that ended with a Q&A with Baker. When she wasn’t able to ask him a question due to an influx of bros “knowledge-dumping,” she decided to DM him a question directly afterwards. He responded, noted her “weird internet presence,” and asked for a reel. She didn’t have one, but she hired a friend who was “great at piracy” to make one using clips from her sitcom and TikTok. Baker told her she was “so fucking funny.” She eventually taped her audition for the part of Crystal in her dorm room and got the part.

More work followed. Wolk was cast in a forthcoming project directed by Jonah Hill. She was initially slated for just two scenes in it, but once on set, her penchant for improv led Hill to increase her scene count significantly. And then, her improvisational mind shined once again in Brian Jordan Alvarez’s hit FX sitcom, English Teacher, where some of her key scenes became viral stand outs. Amidst all of this, she left college and moved to New York.

Through these highs and lows, Wolk has contended with a stomach illness that has made her life one largely defined by physical pain. She describes her hard-to-diagnose digestive issues as akin to her body reacting as if it’s always being poisoned. She posts about her health issues on X often, but her admissions come amidst a throng of cultural takes and personal confessions, which can position the agony of illness as simply another part of her roving stream. It is for her day-to-day life, though, the sun around which all else orbits. “As a chronically ill person, there are periods where I’m doing better, but my ‘better’ is still worse than everybody else's,” she shares. When I wonder aloud if online pile-ons contribute to her physical pain, she somewhat agrees: “I'm sure it's negatively impacted my physical health, but even if everybody loved me, my body will still deteriorate and that puts me in a bad place mentally. Everything begets everything.”

Today, Wolk continues to post to her heart’s desire — even as her film career keeps her busy. She remains on X, where her dozen-plus posts a day frequently invite virality and vitriol. Sometimes, she doesn’t even need to do anything to inspire a stunning dog pile.

When the X account for Anora posted a montage of her scenes, introducing the world to her character, more than two thousand accounts quoted the post to offer up their takes, hate and receipts re: Wolk’s lore and controversy. One troll quoted it saying, “its november 12th and ivy wolk is still alive.” Another offered more intent critique: “every time Ivy wolk catches negative attention on here without fail she goes on a rant about the hate and then will later make another horrendous joke that only makes more ppl dislike her.”

As a matter of general human etiquette, no one deserves to have thousands of strangers calling for their death over online behavior they find annoying or problematic. But this post has an irrefutable point: Why does Wolk continue to exist online when doing so invites this inevitable backlash? I pose this question for Thomas. “A lot of people that Ivy looks up to [like Winhouse and Love] are people that had the public against them,” she replies. “That was part of their narrative and that’s part of Ivy’s practice. But I wish she would stop.”

Wolk has heard this concern — from friends, from her mom, from peers — but she has no plans to go offline. “Older comics are like, ‘You'll grow out of it. You'll stop,’” she says. “Maybe I will. But right now, this has been the past seven years of my life. Most of the accounts are gone, banned or deleted, whatever... but I’ve started new ones,” she says. “I'm the roach that can't be killed.”

Soon after our first interview, I follow Wolk to her stand-up set at Brooklyn bar C’mon Everybody, where she’s guest hosting for comedian Adam Friedland’s show, Funny Moms. I’m excited. Wolk — in our conversation, online and on-screen — never fails to make me laugh, if not sweat a bit from nerves. And on-stage, Ivy Wolk is Ivy Wolk. She’s disarmingly direct as she harps on self-harm, her time in a psych ward, strained sex and masturbation. But tonight, she’s putting on a California valley girl affect. It’s a new style for her, and sometimes the dissonance between her raw material and breezy delivery works. Other times, though, the crowd seems confused.

“I told a guy that I was into that I was a cutter upon first meeting him. That may seem a little abrupt for a first introduction, but for a girl like me that’s really elementary conversation,” she hums. “First date questions include how many siblings do you have and show me on the doll where the bad man touched you?” The somewhat sparse crowd reacts with a mix of glee, discomfort and squeamishness at this unflinching joke delivered so sighingly.

At one point, later in her set, someone walks out. “You were great in Anora,” they yell while fleeing. When Wolk notices another person exiting, she calls them an epithet. “Try being funny next time!” they bark back. I had seen this dynamic play out with Wolk before online, but never in the flesh. It’s almost like I’m in a version of X made physical, and though her fighting spirit is something to witness, I can’t help but wonder: Why does she put herself through this? Why does she have to always up the ante?

Wolk yells again at the long-gone heckler. She describes a group of men she befriended in her neighborhood, before detailing how they’d avenge these slights to her. It’s a bloody affair. Some laugh. Others squirm. But Wolk keeps the joke going. The vibe becomes morose, awkward and then nihilistic. Some laugh along. Others look around. I can’t look away.

Photography: Taryn Segal

From Your Site Articles

MORE ON PAPER

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October

Entertainment

Matthew McConaughey Found His Rhythm

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

30 September