Helmut Lang's LA Art Debut

Story by Jocelyn Silver

Feb 26, 2025

In 2005, Austrian artist and former designer Helmut Lang walked away from his groundbreaking clothing brand, an innovative, minimalist label that became synonymous with ‘90s fashion. He retreated to a centuries-old farmhouse in East Hampton, trading his own designs for simple Levi’s and t-shirts (fans and friends regularly comment on the camera-shy Lang’s buff physique beneath said t-shirts). After three years of quiet, oceanfront living, he re-emerged, leaving fashion behind to focus on his career as an artist. In 2008, he described the shift to W as “an evolution, a progression.”

“I wanted to explore everything I knew on a different level,” he said in the interview, adding that it was “time to grow.” Artist Roni Horn, who described Lang as an “enigma,” said in the same piece that his clothing design “was always sculptural in nature — very material based, very physical, and then sensual and sexual.” As a clothing designer, he worked with textiles ranging from the utilitarian and classic (denim, black leather, velcro, organza) to the unorthodox (his rubber dress was a ‘90s sensation, with its own profile in the New Yorker; a horsehair design was acquired by the Met). When a fire in Lang’s building on SoHo’s Greene Street damaged much of his legendary clothing archive, he threw the pieces that remained in a shredder and turned the bits into a sculpture, preserving the textiles over the designs themselves.

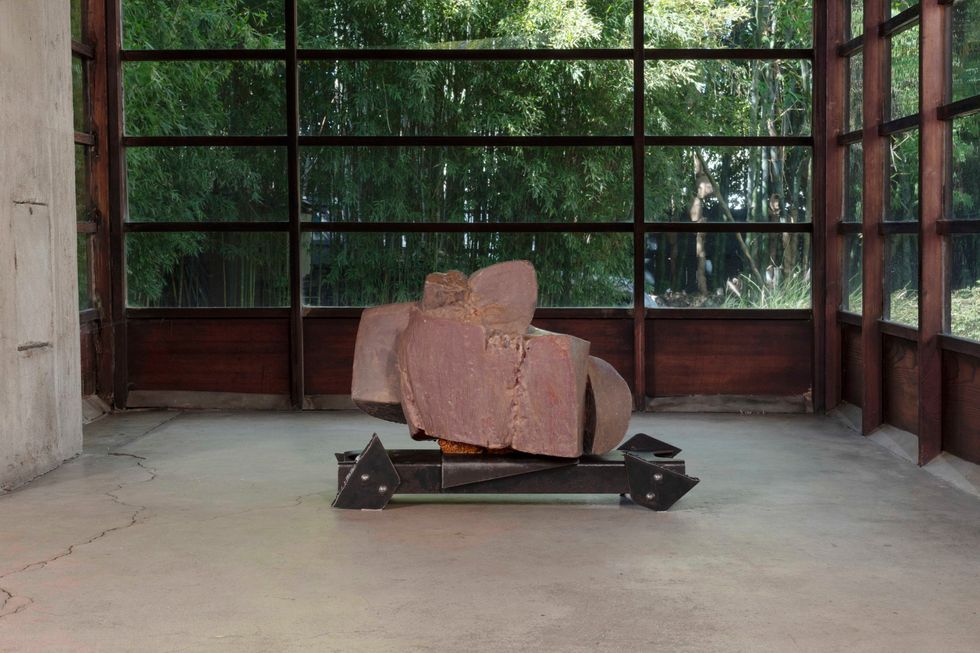

In the 15 years since he came out as a full-time artist (though he’s been exhibiting art since 1996), Lang has maintained a focus on materials, creating tactile, raw-looking sculptures in the barn he converted into a studio. Last week, he presented a solo show of said sculptures in Los Angeles for the first time, in an exhibition curated by longtime collaborator Neville Wakefield. Titled “What Remains Behind,” Lang’s first solo institutional exhibition in Los Angeles features austere sculptures made from unorthodox materials, like rubber, wax and mattress foam. “The emotional weight comes in by what I do with [these materials], and I prefer the outcome not to have predetermined meaning,” Lang explained to ArtNet. “Materials are just materials despite their past.”

At “What Remains Behind” — running through May 4th at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House in West Hollywood — Lang morphs the soft, malleable materials into something firmer and more severe. Described in Wakefield’s elegiac exhibition text as “fist-like forms,” Lang’s sculptures, though abstract, are almost figurative, taking on different lifelike shapes depending on the viewer’s perspective. A short, squat sculpture feels molded around a shrouded entity, while the taller fists, described as punching towards the sky, seem extruded from the Earth. Rectangular monuments (one is called “consenting position”) look as alien and mysterious as the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey. The sculptures’ brown coating feels fecal, which takes on a cheeky, dirty meaning when paired with all the fist(ing). My date for the opening memorably and accurately described one sculpture as “the shit dick.” I still wanted to touch it, the texture like craggy fried chicken skin.

Lang’s sculptures loom over the Schindler House, long shadows pooled across the floor. The innovative, Modern house, designed by fellow Austrian Rudolph Schindler in 1922, had an indoor-outdoor, open plan eons before such styles came to the mainstream. Inspired by a multi-family campsite Schindler visited in Yosemite, it features elements of traditional Japanese and Viennese design, with two interlinking L-shaped apartments intended for two different families to share the space. You move through the house via sliding panels against cool, stark concrete walls; in lieu of bedrooms, there are rooftop sleeping baskets.

“The psychic architecture of the storied house exists in the conversations around light, space, sex, the boundaries between inside and outside, between people seeking new means of manifestation that still cling to the patinated concrete slabs and fill the silent spaces in between,” writes Wakefield. “Within this real and imaginary framework, the work of another Austrian emigree lends its own version of what it is to be human to the concrete forms and enclosures that now house it.”

The mystery and sex of Lang’s sculptures (one is called “prolapse I”) pair well with the history of the house, where relationships were blurry and fluid. Schindler’s friend and architectural rival Richard Neutra lived with his family in one of the apartments; years after Schindler’s wife, composer and editor Pauline Gibling Schindler, left him, she moved back into the house and stayed there until her death, sometimes sharing quarters with her much-younger lover, the legendary composer John Cage. I’m not sure if they were in a polycule, but it feels close enough. What do you call a 1930s polycule? The Great Depression.

Lang’s muscular work is at home in the house. The pieces have a “chimeric quality to them,” Lang told Frieze. At the opening, I used the bathroom and wondered how all this decades-old plumbing would handle the results of the acts implied by the sculptures — probably not well. But they really looked like they belonged.Photos courtesy of MAK Center for Art and Architecture

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October