Eugene Lee Yang never thought his "I'm Gay" video would do well. In fact, he wasn't really sure what to expect at all.

Sure, he could use our obsession with the cult of internet celebrity to give "I'm Gay" an initial push, a reason for people to watch, something for his millions of followers and subscribers to talk about. But after the buzz blogs had picked apart the announcement, how would his fans react? Especially to a decidedly high-brow piece of art combining interpretative dance, dramatic camerawork, and a downtempo Odesza track? Something, undoubtedly, a far cry from the relatable, nice guy authenticity his audience had grown to expect from him.

"I had this inherent fear and assumption that people would not respond to it," he admits, crossing his legs on the sofa of his VidCon hotel room. "I carried that old assumption people have about internet — that it's quantity over quality. I had the old-guard assumption it wouldn't do well."

Yang takes a deep breath, "But the output I'm getting from it is so much more important." He pauses, before describing the similar responses he's received for the "severely-abridged queer history" lesson he performs as part of The Try Guy's national tour, Legends of the Internet.

"It's not just magnified, it's important. I've never felt more invested in being more bold with the work I want to make in the future," he smiles — that small, side-mouth quirk that's propelled him into fan-fiction stardom. "Now, I can finally dash this assumption."

For those unfamiliar with Yang, the 33-year-old internet personality initially shot to fame as one of The Try Guys — a group of BuzzFeed video employees whose goal was, simply put, to try out new things that would normally be considered outside of the straight, male comfort zone. And while they tackled everything from becoming bald to UFC fighting, some of their most infamous videos were the ones in which the Guys did drag, donned high heels, or wedding dresses — tasks designed to push straight, white, heteronormative men outside of their comfort zone. Except, Yang didn't actually fit into any of these categories.

That said, Yang's always occupied an interesting position within the group as the sole person of color and only openly queer member. And while he's always been a vocal proponent and advocate for the LGBTQIA community, he had never definitively said, "I'm gay," until the making-of this video.

"I was clearly queer to a general Western, younger audience. Constantly winking at the camera in regards to people knowing I wasn't heterosexual," he says, before crediting his fans — some of whom told him that his videos had inspired them to come out to their parents — as the catalyst for "I'm Gay."

"I was skirting the subject, sort of beating around the bush, even when I was directly asked about it, because I'd kind of revert back to the family dinner table where nobody's talking about it, even though they may know," he said. "And when I realized that this was a direct reflection of my relationship with the audience... I realized I wasn't giving [my fans] as much as I could."

However, this metaphorical family dinner table proved to be a difficult thing to overcome. The son of Korean immigrants, Yang grew up in a small Texas town attending a conservative Korean Presbyterian church in the shadow of the AIDS crisis — a moment in history that posited the queer community as a potential threat within mainstream American media.

"It was this classic cocktail," Yang reflects. "I had this sense of otherness, where I was constantly looking from the outside in at myself. I never had full-fledged ownership of my identity until I graduated college, because I was so informed by all these external factors that were so oppressive."

For many Asian-Americans, otherness is something we've been conditioned to co-opt as a formative identity. As Yang points out, while every minority group can attest to the idea that we're been trained to view ourselves through the perspective of older, straight, white, cis men, it's "hard to hide our ethnicity," and that became the first hurdle he had to overcome.

"I was clearly detaching myself from a lot and distancing myself from a lot of truths, which were very hard to confront, because I was seeing it from the side of people who were saying it was bad. So I saw myself as bad," Yang says, pausing for a moment to collect his thoughts. "It took me a long time, even in college. That came with its own set of trials... this whole set of stereotypes and rules I had to confront."

Because though he attended USC in Los Angeles, he continued to feel like a subject within his own story — continually being told by his professors that his identity as an Asian filmmaker was "edgy." Yet, like many minority creators in the arts, Yang continued to wrangle with the question, Why is my perspective even considered transgressive in the first place? Why am I not allowed to just say what I want without having arbitrary qualifiers attached to my work?

"I was always told, again and again by others, that I was different," Yang says. "But weirdly, what oppressed me in my childhood was what I could sell in my career."

At this point, we begin talking about his time in media as a producer for BuzzFeed — as a content creator who was forced to embody the quintessential millennial affect of upbeat candor — and occupying this platform at a time when media decided diversity was profitable. For his part, Yang isn't as cynical as me about the identity-focused shift that occurred during this time, though he does admit that it is a very real issue he hopes dissipates in the next 10 years or so.

"There's been this evolution to see the ways we represent ourselves and how we speak about it," Yang notes. "There's a progression of what do we have to do or say to first be seen as 'mainstream' or 'accessible' or 'relatable' or 'sellable.' You have to think in steps."

He refers back to when he "first started doing videos about my Asianness" and "pimping out the right jokes from my perspective about my identity" — something embodied by the things like the (incredibly on-the-nose) "If Asians Said Stuff White People Say" concept.

"We see these things happening, and now we're experiencing this culture where we've at least broken through enough of that ceiling," Yang pauses for a moment, before rephrasing, "Perforated it enough. To where the people who don't want it to happen are swinging so hard against it, which explains the nature of discourse today on social media."

Yang hypothesizes that this is perhaps a factor in his more cerebral work finally been able to flourish — this desire to explore the unique intersections of identity each of us occupy.

"It did take time for me on these different paths for it all to converge," he admits, before we launch into a conversation about the next barrier that he continues to grapple with internally. Namely, the ever-present conflict between his external presentation as someone who feels the need to rebel against media-perpetuated emasculation of Asian men and his internal desire to occupy a truthful space in which he is able to explore his more femme side.

"We all grew up with a certain amount of binary, Koreans and lot of East Asians, especially," Yang says, before recalling the ways in which he was treated differently from his sisters as the only boy in the family. "It was just ingrained in everything we did — you're a boy, you're a girl. Like, I didn't know how to work a stove or microwave until I was 13."

However, when Yang was 13, his parents divorced. And while it was a shock to him, Yang credits the divorce as the "catalyst" that helped both of his parents become "way more open-minded" and something that has inspired a lot of his subsequent work.

"[I want to ask], 'What's the dynamite that some of these structures need to crumble?" he says, adding that both of his parents have since moved on and flourished. "Mine was the divorce, which was the craziest but most amazing thing that could've happened to my family."

That said, the divorce still didn't erase an entire childhood of having rigid gender binaries and the notion of filial piety ingrained within him. Yang notes that at the beginning of his video career, he felt the need to "police" his dress or the way he spoke, "because I didn't want to look soft."

"When I first became notable online, people generally didn't know I was gay. And as one of the first Asian faces in casts of non-Asians, I had to beat everybody. I had to be better. I had to be stronger. I had to be smarter which, again, fed into my Asian complex," he says, explaining that he felt burdened to be seen as the antithesis to the Asian male stereotype perpetuated by mainstream pop culture. "It was complicated, because I didn't want to be the soft, submissive, wilting, quiet Asian person. There's nothing wrong with that, but we are constantly in flux with that relationship."

For Yang, it took years of self-reflection to even reach this point where his family and fans, "could witness me proclaiming... this thing I've been screaming in my head for 33 years." Naturally, he now hopes that his art acts as a revelatory shortcut of sorts for other young, queer Asian-Americans questioning their identities.

"Sometimes we think it's us versus something else and that's what gets us into these weird quandaries of how to police our own gender and race. And that's the most difficult thing — for gay people and Asians, in particular — [stopping them from] releasing that self control," Yang speculates. "So I want my work to speak from this idea of, 'How does one maintain and navigate these very particular relationships under circumstances that sometimes take more time, more care, more self-discovery?'"

And the first step for him? Well, it all comes back to the making-of "I'm Gay" — that definitive, unquestionable proclamation of an identity he spent so long being scared of. Something that signaled the ushering-in of a Yang who felt empowered enough to finally own his identity, even if it happened to be something completely at-odds with the disparate cultures he was raised in. But it's also something he believes is necessary for his growth — not just as a person, but as an artist as well.

"There was the framework I was operating in, and I had to confront that," Yang concludes, that impish grin appearing on his face once last time. "I needed to inhabit myself in order to be an effective artist-filmmaker and be a more fully-realized person."

Welcome to "Internet Explorer," a column by Sandra Song about everything Internet. From meme histories to joke format explainers to collections of some of Twitter's finest roasts, "Internet Explorer" is here to keep you up-to-date with the web's current obsessions — no matter how nonsensical or nihilistic.

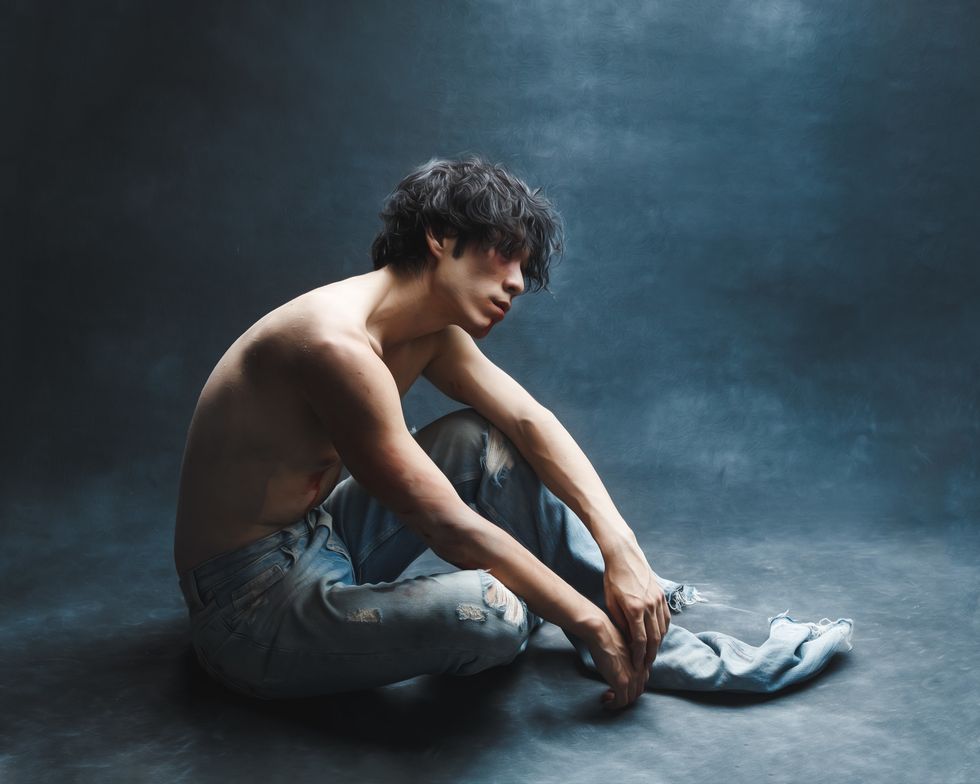

Photos courtesy of JD Renes Photography

From Your Site Articles