East Never Loses' Queer Mahjong Reclamation

By Lisa Kwon

Sep 24, 2024

East Never Loses founder Angie Lin dreams of making her own mahjong sets, which would make her the first queer woman — let alone the first Asian woman — to sell the centuries-old tile-based game in America.

“Americans have a lot of history with mahjong that I don't want to discredit, but I want to bring back what this game really represents, who it is for, and the stories that are attached to the original way of playing mahjong,” she tells PAPER. “I don't take away the love of the gameplay; I just want to reclaim it in a sense of giving people the context that it needs.”

While Lin’s mahjong sets remain a work in progress, a crucial part of her reclamation is to party.

There are two ways to enjoy an East Never Loses function. One is through Lin’s monthly QQ Academy, for players seeking some coaching or competition while tucked away in a garden space in the Arts District’s Hauser & Wirth in Los Angeles. Here you’ll learn that Joseph Babcock coined it “mah-jjong” because its original name, máquè, didn’t sound Chinese enough as he endeavored to popularize it in America; it was marketed as an ancient game from the East when really it originated in the mid-1800s; and white American women championed it in the 1900s after realizing that teaching it allowed them some financial independence from their husbands.

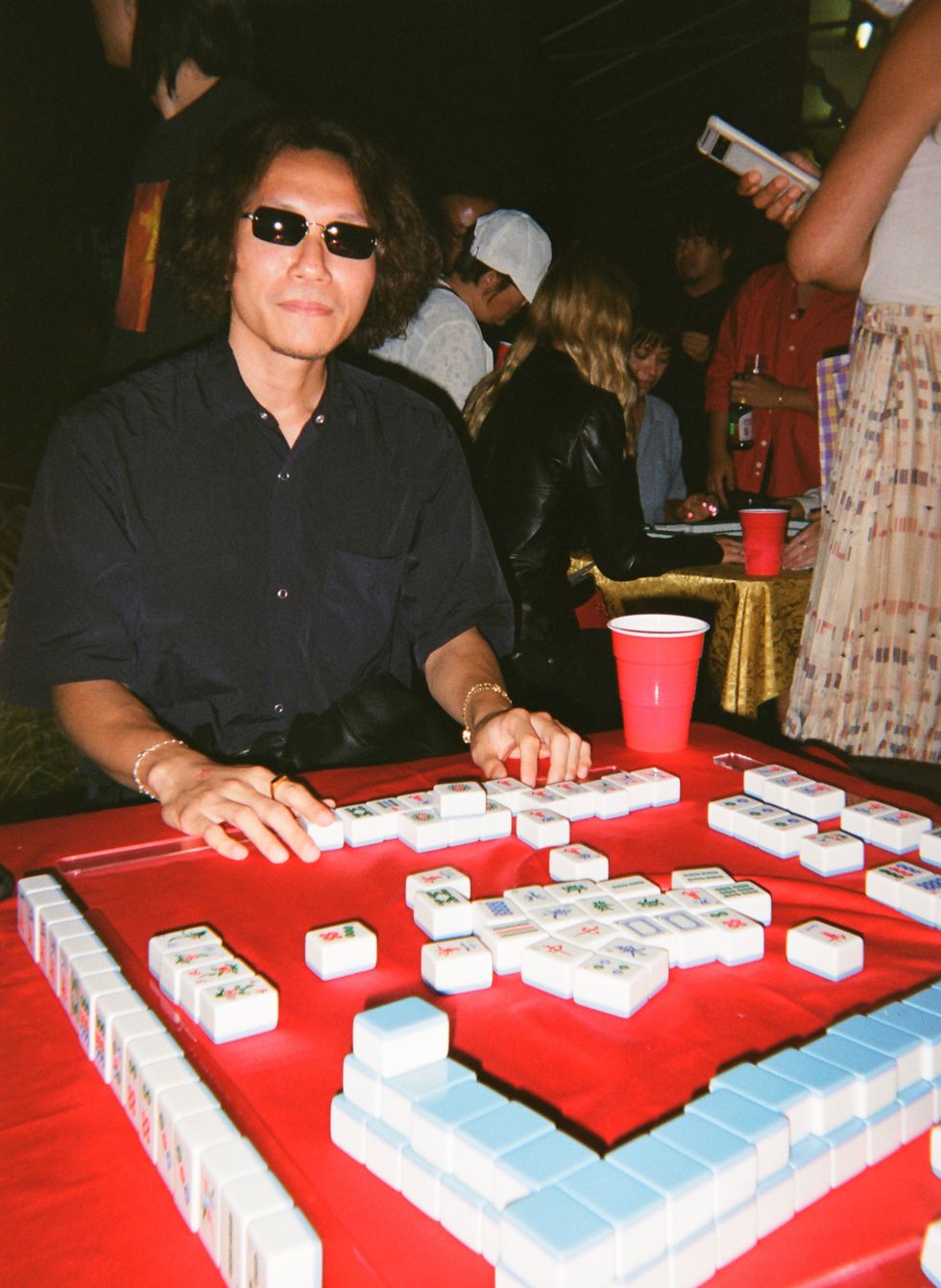

If garden chic is not the vibe, East Never Loses’ monthly ragers invite party-goers into San Gabriel Valley, Los Angeles’ densest Chinese and Taiwanese enclave, for Szechuan food, frosty bottles of Tsingtao, irreverent dancing and four hours of mahjong. From Jianghu, a former dim sum restaurant-turned-club, almost 200 eager mahjong players gather beneath an auspicious red and white glow. A bubble machine emits lemongrass-scented bubbles to repel mosquitos (genius!) from the lime green, baby blue and sparkly pink mahjong sets that decorate the outdoor patio tables. On one side of Jianghu, a line has formed by 9 PM and it comprises attendees who are new to mahjong and waiting to be taught by Lin or one of her teaching assistants. Every now and then, what sounds like twittering sparrows cuts through the excited conversations that fill every corner; this is the song of the noisy, shuffling tiles that signals to people that a new round of mahjong is about to begin.

It’s more theatrical inside Jianghu. From the front of the room, a DJ beckons the boozier attendees towards the stage with a tantalizing rotation of R&B deep cuts. Statues of Buddha and mythical martial artists with exaggerated 26-pack abs (I counted) command the hazy room, standing alongside young party goers and older men who blend into the mise-en-scène like Jianghu’s black vinyl banquettes.

Pay no mind if the latter group does not want to talk to you.

“[Jianghu] is 110% run by [San Gabriel Valley] gangsters,” Lin notes. While looking for venues to host her parties, she befriended James, the “well dressed and fly” owner who went on to introduce her to his regular patrons who retreat to the club and restaurant to reminisce on their glory days. In awe of their aura, Lin set out to seek the good graces of James and his patrons. This year she forged a handshake agreement to host her East Never Loses parties at Jianghu, but not without navigating her own presentation and dynamics.

“They're so Chinese, and they're so in their own world that this young Asian girl being like, ‘I want to throw a mahjong party here’ was a very weird thing for them,” she says.

One of the Jianghu regulars, known to have operated a network of mahjong dens in Taiwan before moving to America, runs up to Lin as she ushers a new group of four people to a mahjong table. “Lu Ge!” she exclaims his name as they embrace. Lu Ge beams at her, not unlike how one would look upon his goddaughter.

Once beginners graduate from the first-timer tables, Lin and her teaching assistants move them over to a larger community play area, where people hover over tables and wait to play with newfound confidence and style. At times, money comes out, too. Here I meet Chris Chavez, who is nostalgic for his childhood when he played dominos while growing up in El Sereno, a nearby historically Latino neighborhood just a few miles away from Jianghu. The tactile qualities of mahjong appeal to Chavez, and the meet-ups offer him a bonding experience with others that he doesn’t get online.

“I think online allows me to make friends with a specific or special interest,” he says. “But I’d take mahjong outside of here because of nostalgia [for dominoes] and also to connect with my community. Especially with the Latino community in El Sereno and a lot of our Asian neighbors, there's a disconnect because of language, but I think this is a cool bridge because we’re sharing the same space and we don’t have to talk.”

This is all according to Lin’s plan, who wants East Never Loses’ events to bring people together as friends, community organizers, roommates or romantic partners. Trust her: she has a proven track record of matchmaking through mahjong.

“It’s so heartwarming for me to see people sit at the table together and then literally after the game be like, ‘Do you guys want to get dinner together?’ Some of my closest friends now I've met at the mahjong table,” she says. “On top of that, I did a mahjong matchmaking event one time and had people make out the day of.”

Lin fell in love at the mahjong table, too. In February, while hosting mahjong play at director Sean Wang’s (of recent Dìdi acclaim) release party for his short film Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó, she met Ellen Lu, who had initially come over to watch the game.

“I would see [mahjong] around when I was younger, but [my parents] didn't want to sit around and teach kids,” says Lu, “so when I saw it at the premiere, I immediately wanted to go over because I wanted to learn. But then I saw Angie and that overshadowed everything.”

Lin gleefully corroborates their mahjong-incited love story. “The first time we hung out as friends, I was like, ‘Why am I so drawn to this person?’ She took off her jacket when she came into my house and I was like, ‘Her shoulders are so hot.’ I was freaking out to the point where we smoked a cigarette inside my apartment building. After a few more hangs I was like, ‘Okay, I am gay.’ We basically have been inseparable since.”

Lin credits mahjong for being there from the start of her understanding of her queerness. In 2019, Lin moved to Taiwan for a band that she was managing; she felt compelled to finally learn to play. Eventually she found a group to play with into the late hours of the night. Whoever won the most money would “buy everybody drinks,” and the group would “party until 2 or 3 AM, and then do it again.” To commemorate this time in her life, Lin bought her first set at a store called Dongfang Bubai, which translates to “East Never Bows.” To add another meaningful layer, Dongfang Bubai is the name of a fictional martial artist in wuxia novelist Jin Yong’s universe (“the Tolkein of China,” according to Lin) who has become a queer icon for Asian people because of how he bends his gender presentation and sexuality to assassinate his enemies.

“Thinking about that, I was like, ‘This is a great name.’ It represents my Asian identity, my queer identity, and also gives homage to my first mahjong set that started [East Never Loses],” Lin says.

Encouraged by the safe space that she’s created for third culture and LGBTQ+ adults to meet new people, Lin wants East Never Loses to reach older generations, too. Starting in September, her QQ Academy will offer free admission to anyone who brings someone from a different generation to learn or teach mahjong. Also coming in this fall: a collaboration with Little Fatty to throw a weekly mahjong den on Sundays.

As crisper months approach, it’s going to get increasingly difficult not to hear the sound of chirping mahjong tiles throughout Los Angeles’ artsy spaces. Under the red glow, in Lin’s rambunctious classroom — what a stunning place to fall in love with a person, life, and learning something new.

Photography: Lenne Chai

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October