Care

How a COVID-19 Emergency Amendment Act Affects Incarcerated People

by Abigail Glasgow

01 May 2020

As a Black man convicted of murder in the early '90s, Joel Castón's story paints a portrait of the historic, gross inequity embedded in the American justice system for lower income individuals and people of color. He's shared the story of being in a maximum security institution, with 21 hours of lockdown and three hours of recreation per day — where only an hour and a half of recreation was actually granted. He's deconstructed the chronic trauma of handcuffing, and spoken to the anguish that comes with a release date of "deceased."

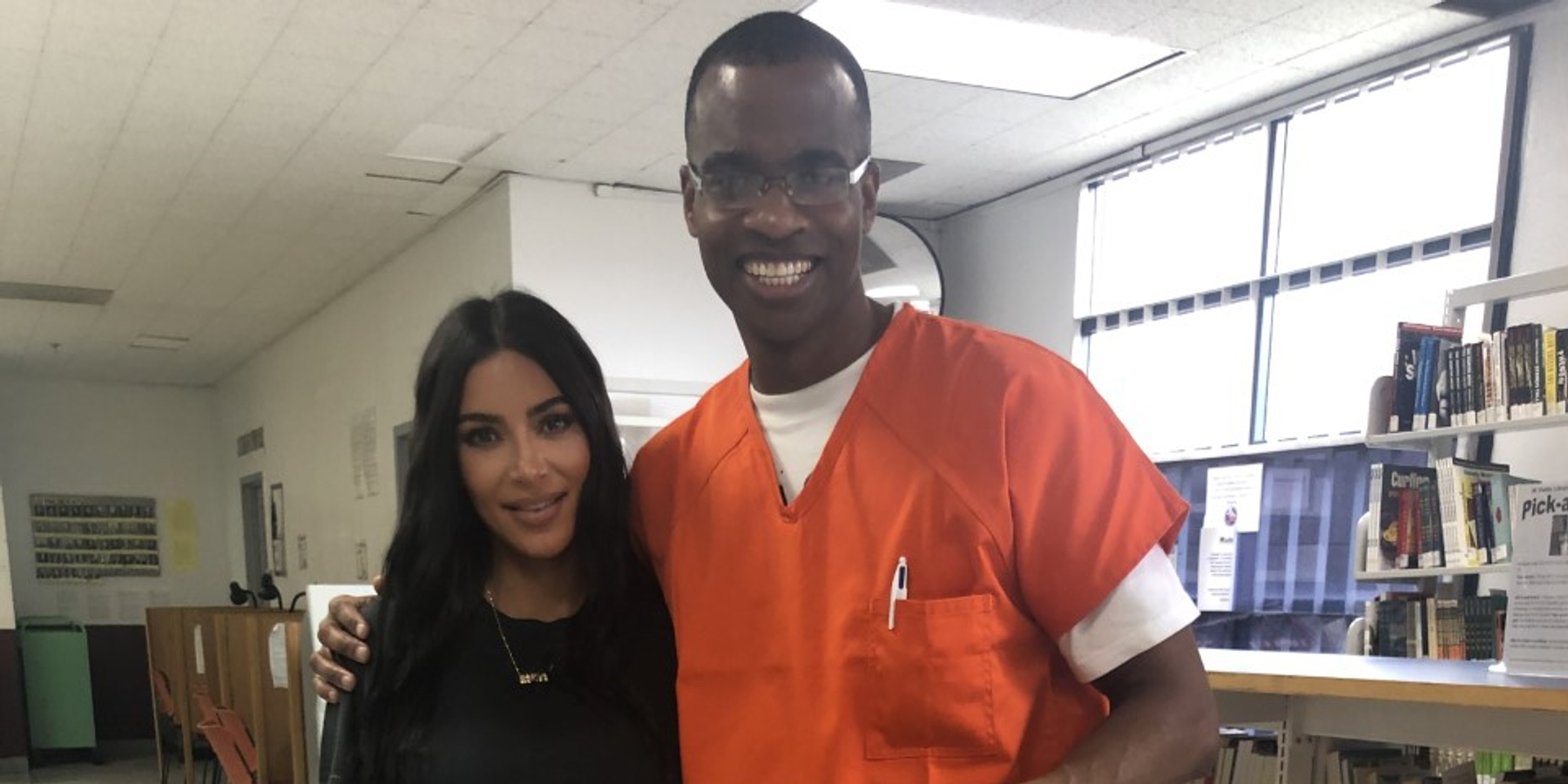

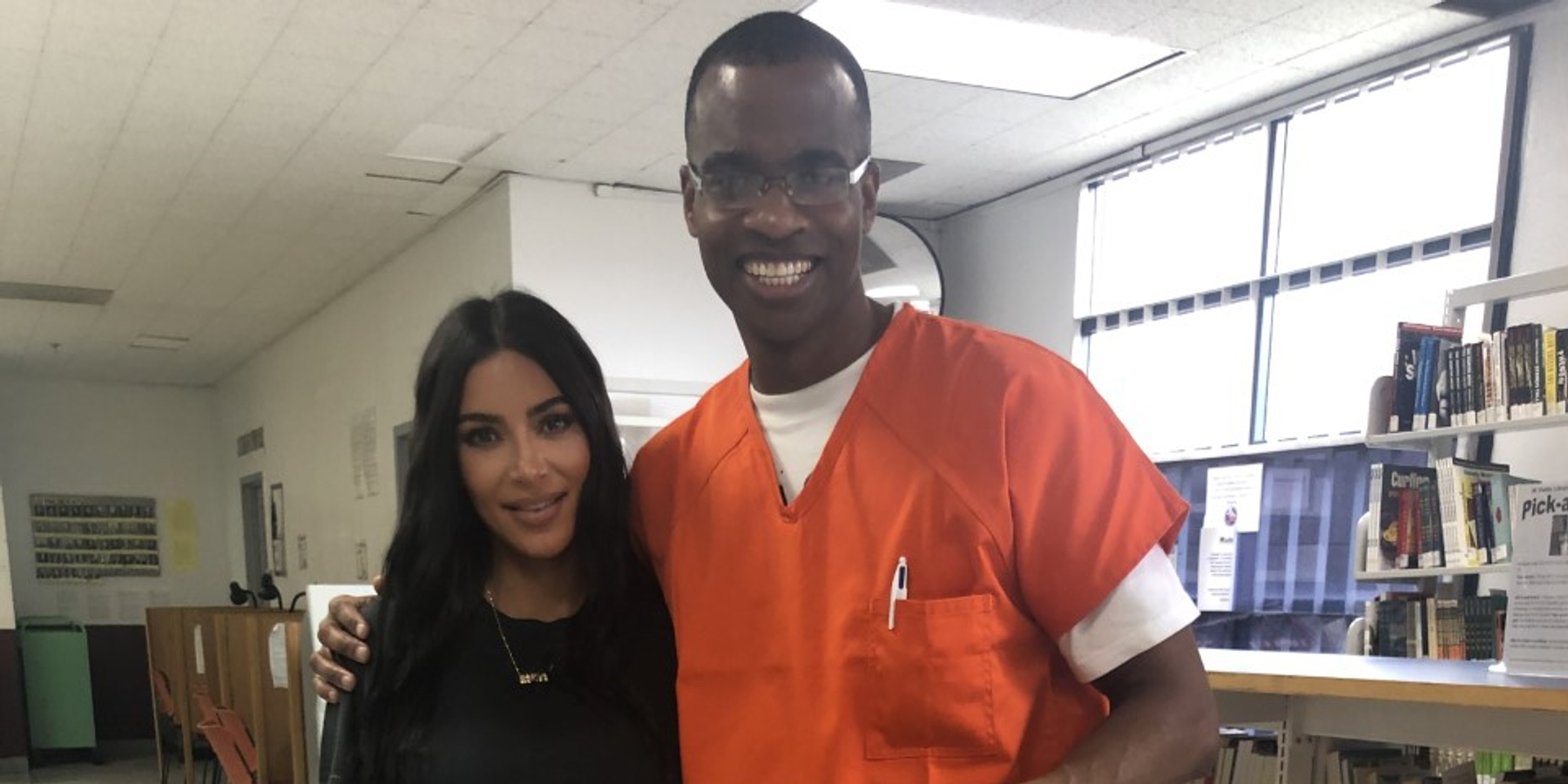

And because of his story, from juvenile incarceration to rehabilitation, he was one of two incarcerated residents approached by Kim Kardashian West's team for her new, two-hour documentary: The Justice Project, which premiered in April on Oxygen.

The doc follows multiple Americans across age groups who have lived through the criminal justice system. Kardashian West's goal is to greater understand the law in an effort to give these individuals a second chance in society. While Castón's footage did not ultimately make The Justice Project's final cut, his interview with Kardashian West was one he says totally shifted his mindset.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I was frustrated by the casualty of language people used when addressing it. "New York is going to go on lockdown! Better get out while you can," or "I've heard they're closing the borough borders. We'll likely be confined for weeks." Perhaps for the first time, during this period of extended quarantine, people are relating to the idea of "confinement" that those incarcerated literally live every day.

So I got on the phone with Castón to get his take on the state of the union when it comes to incarcerated residents, and what his life looks like right now, particularly in the face of the COVID-19 Response Supplemental Emergency Amendment Act of 2020. The bill was unanimously signed by the District of Columbia's Council on April 7.

For incarcerated residents, the bill states that "the court may modify a term of imprisonment imposed upon a defendant if it determines the defendant is not a danger to the safety of any other person or the community." This applies to nonviolent and violent offenders alike and, more importantly for Castón's case, explicitly states that good time credit may be "retroactively awarded" to those who were incarcerated before August 5, 2000. While the bill was timed to the pandemic's stateside onset, the means of applying good time post factum has been a concept in the works amongst advocacy groups for some time.

Related | Break the Internet: Kim Kardashian

This bill is a first step to depopulating those inside, but there's still more to be done when pursuing the protection of those most vulnerable in our society, especially in light of COVID-19. Organizations from Justice Policy Institute and The Bail Project to campaigns like #FreeOurYouth and #FreeBlackMamas are working tirelessly to educate the public in both supporting these communities fiscally with donations or through virtual organizing. Their work highlights how the lives of incarcerated residents far outweigh their crimes.

This DC measure also follows a memo released on April 3 by US Attorney General William Barr ordering the Federal Bureau of Prisons to identify "at-risk inmates who are non-violent and pose minimal likelihood of recidivism and who might be safer serving their sentences in home confinement." However, his plan has been criticized because these inmates will be identified by an algorithm that the Marshall Project reports is biased toward white people. According to the Prison Policy Institute, there are only about 226,000 people locked up in federal facilities compared to the nearly 1.3 million in state prisons. And while some states are leading the way (900 people were released by March 31 in New York and California will free 3,500 over the next 60 days), bold, swift reforms at both the state and federal levels remain necessary.

Below, Castón talks about how COVID-19 Emergency Amendment Act affects incarcerated people like him.

Let's talk about the new COVID-19 bill. What could it mean for someone like you?

Particularly for an incarcerated resident, it's definitely a dream come true. This new bill deals with individuals [like me] who specifically were sentenced in the '80s and '90s [and] have already served too much time in prison. It would allow good time credit to be applied [retroactively to our sentences]. In my case, I don't have any disciplinary reports since being incarcerated. So, it's a meritocracy; it pays off to be a model citizen.

I've served 25 years and you have other guys who have served 30 or 40 years. We are individuals who have definitely aged out of crime [Laughs]. New data proves that we're least likely to recommit an offense. Our recidivism rate is extremely low. We're not a public safety risk to the community. I'm applauding the council members for [signing] such a measure. Because [this bill] definitely does depopulate the prison and allows individuals who have a proven track record of not being dangerous and being rehabilitated to regain their freedom.

It's difficult to deconstruct exactly what this all means.

I fall in the category of old law co-defendants: I was sentenced prior to the year of 2000 with an indeterminate life sentence. When I look [at my release date], I have to see the word "deceased." Psychologically, it discourages you when you're living with a death sentence and you know that you haven't even lived 20 years in society and that your life is taken away from you. That kills the spirit.

Back in 2016, my colleague and I called a meeting with other guys who were sentenced to life (all of us were kids when we first came to prison) to discuss the sentencing disparity [between our age group] and the new guys. [Sentenced after 2000, the new guys get] a maximum release date, and they also have a home confinement date. We got some of the sentencing work from the younger guys and I started putting [a comparison] together and sending it to different advocacy groups and council members. Those exact initiatives are allowing us [older guys] to receive release in regards to the COVID-19 Emergency Act. We've been fighting for it.

I'm ecstatic that I have a meaningful opportunity to gain my freedom. Kudos to the Mayor of this wonderful city and the council members that would allow such a timely initiative to take place. You gotta understand that across the nation these mandatory minimums are keeping people in prison longer than they should be. To allow us to go under those minimums is noteworthy.

Speaking of noteworthy, can you talk about the experience filming Kim Kardashian West's The Justice Project?

At that time I must admit, I didn't think my story was anything remarkable. I thought that any person growing up in the inner city or an underserved community has the same ups and downs that I've been through. But meeting Kim forced me to look at some of the things in my family structure that I had overlooked. I realized there was a lot particularly about my upbringing and my childhood that was traumatic — that I literally buried.

I was more nervous — not so much about meeting someone who's an icon— but more about sharing things that are dear to myself and my family. [But] sitting in front of [Kim], I felt like I was sitting in front of a home girl. Even before the interview took place, we were already in conversation. She was so relatable. Immediately, we started talking and the cameramen were like, "Whoa, let's get this on camera." I felt so confident and comfortable sitting in front of her. I connected with that immediately. I felt like this is Kim from the block. Let's sit here and let's just talk. And that's exactly what we did. And I had such a wonderful time. Not one moment did it dawn on me ya know this is the icon Kim Kardashian [West]. This is just Kim on a social visit coming to holler at one of her boys. That was the vibe I got from the beginning to the end. It took that ordeal for me to say, "Wait a minute, my story does have value, and it is worth sharing." That opportunity really shook me in a good way.

Has speaking with Kim made sharing your story easier?

Easier in a sense of making me more comfortable. Kim was the catalyst. I will be eternally grateful for her. She awoke inside of me that which lies dormant deep within. And I didn't know when I was gonna allow it to come out. When an individual grows up in a broken social construct, it isn't necessarily that the individual is bad. It's that social construct that he or she grew up in that made them that way. Kim comes from [a different] social construct, and yet has the empathy to relate and to connect. Talking to Kim, she was so transparent, all I saw was her humanity. Her words were consoling, her nods were knowing and her smile was building more confidence inside of me. That's why I'm writing my memoir, thanks to Kim.

In fact I wrote Kim a letter [about] what I suffered as a kid with my sister being raped, my bout with selling drugs in the beginning of elementary school, my sisters being on crack and my dad being on crack, me being adopted; and how that affected me. I wouldn't have referenced any of that, if it weren't for meeting Kim. It has really been captive for years. I realized the more I can share, the stronger I feel. It doesn't make me well up with tears like it once did. So it actually gives me power and strength, and I'm extremely grateful for that opportunity.

Right now, many in quarantine are using the terms "lockdown" and "confinement" to describe their experience. Do you see a discrepancy between this and your experience on the inside?

Groundhog Day, that's the movie where the guy woke up and every day was the same? Inside a prison, every day is the same... what was once abnormal becomes normal. You get used to an eight by nine cell or a matchbox. When something like this pandemic takes place, mentally, it takes you back to traumatic experiences. You become comfortable in crisis. You have to adapt and adjust. You have to come up with a plan on how to allow your days to get by. So I came up with my own plan, and it was based largely on reading, meditating, yoga, listening to NPR, exercising, going to bed and starting all over again. My creative side comes into place. I start daydreaming a lot, I start visualizing a lot, I start writing more. That is what carried me over these 25 years. Staying faithful to regimen. And I believe that is a recipe for success no matter where you are.

In light of the pandemic, people are being forced to look at their lives in a different way now that their mobility is so restricted. Do you think there's now a silver lining in how people think about incarceration?

I like when you say, "silver lining." COVID-19 is happening for the entire globe. I remember playing video games when I was younger and it had a reset button on there. When you lost the game, you could hit the reset button and start all over. I think the entire world is going through a reset moment right now. We got so far away from being humane, that we needed something like this to bring us back to our senses — to recognize that I share this planet with others, and it behooves me to be nice to my neighbors. The pandemic has woken us up to see people caring like they've never cared before.

Can you talk about your experience building the Young Men Emerging (YME) mentorship program?

I started it in the DC jail. The official launch date was February 2018. Since launch, we've probably had well over 200 guys who have matriculated inside the community. My colleague Michael Woody and I are the founders, but it would have not taken off if [the agency] didn't approve of it. So the director, Quincy Booth, needs to be praised. The Department of Corrections, the DOC, too.

We have created a mentorship program consisting of older gentlemen who have served over 20 years of time in prison, who can model to younger generations under these difficult circumstances. We wear many hats: We are counselors, we are like big brothers, we are confidantes, we are teachers, we are instructors.

Every day we have programming largely led by us, but also we have a number of service providers and volunteers from society who come in and bring their curriculum. It's really like a learning center. We talk about basically everything: Victim impact, restorative justice, education, financial literacy and healthy masculinity. And we are pushing civic engagement. We're breaking the street culture. We're teaching a sense of values for a group of guys who probably didn't feel valued in the past. And we're hammering home the idea of being a community member.

We have a banking system with deposit money the [young men] use to have access to the radio and other things we have in the community. It creates a sense of normalcy. So when you're inside the YME you don't feel as if you are incarcerated. [We're] basically serving the younger guys we once were, when I first came to prison. So it definitely gives me a sense of great pride to be able to minister to a younger me. And let them have a completely different experience than the one I experienced.

That's why I wrote my book, Currency Catchers, to penetrate a space that was not traditionally tread upon [for people of color]. Being forced to sell drugs [and] selling candy as a kid, that put the entrepreneur spirit inside of me. I finally found an outlet where I can exercise this passion in a legal way, which is investing. [I want] to show [mentees] this is a road for them. I want to show that if you look like me or come from where I come from that doesn't mean you can't do the things I'm doing. The great equalizer is education. Giving access to education, and treating us as human beings.

It's crazy that that has to be a novel idea.

It's easy. If you treat an individual like an animal, that's how he's going to behave. But if you treat him like a person, he will step up to that value system. I haven't been in society, but when I think about society I think about the fact that it has neighborly activity taking place. So I'm looking forward to holding community conversations in society.

Photos courtesy of Department of Corrections/ the DOC